Disrupted Expectations: Young/Old Protagonists in Diana Wynne Jones's Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolkien, Hispanic, Koonts, Evanovich Bkmrks.Pub

Fantasy for Tolkien fans Hispanic Authors If you like J.R.R. Tolkien, why not give these authors a try? Kathleen Alcala Machado de Assis Piers Anthony Robert Jordan Julia Alvarez Gabriel Garcia Marquez A.A. Attanasio Guy Kavriel Kay Isabel Allende Ana Menendez Marion Zimmer Bradley Tanith Lee Jorge Amado Michael Nava Terry Brooks Ursula K. LeGuin Rudolfo Anaya Arturo Perez-Reverte Lois McMaster Bujold George R. R. Martin Gioconda Belli Manuel Puig Susan Cooper L.E. Modesitt Sandra Benitez Jose Saramago John Crowley Elizabeth Moon Jorge Luis Borges Mario Vargas Llosa Tom Deitz Andre Norton Ana Castillo Alfredo Vea Charles de Lint Mervyn Peake Miguel de Cervantes David Eddings Terry Pratchett Denise Chavez Eric Flint Philip Pullman Sandra Cisneros Alan Dean Foster Neal Stephenson Paulo Coehlo C. S. Friedman Harry Turtledove Humberto Costantini Neil Gaiman Margaret Weis Jose Donoso 7/05 Barbara Hambly Connie Willis Laura Esquivel Elizabeth Hand Roger Zelazny Carlos Fuentes Tracy Hickman Cristina Garcia Oscar Hijuelos 7/05 ]tÇxà XätÇÉä|v{ If you like Dean Koontz 7/05 Janet Evanovich, Romantic mysteries you might like: Pseudonyms of Dean Martin H. Greenberg filled with action Susan Andersen Koontz: Caitlin Kiernan and humor. J.S. Borthwick David Axton Stephen King Stephanie Plum Jan Burke Brian Coffey Joe Lansdale Dorothy Cannell Mysteries K.R. Dwyer James Lasdun Harlan Coben One for the money Leigh Nichols Ira Levin Jennifer Crusie Two for the dough Anthony North Bentley Little Jennifer Drew Three to get deadly Richard Paige H.P. Lovecraft G.M. Ford Four to score Owen West Robin McKinley Kinky Friedman High five Sue Grafton Graham Masterton Hot six Heather Graham If you like Dean Koontz, Richard Matheson Seven up Sparkle Hayter you might like: Joyce Carol Oates Hard eight Carl Hiassen Richard Bachman Tom Piccirilli To the nines P.D. -

K¹² Recommended Reading 2012

K12 Recommended Reading 2012 K¹² Recommended Reading 2012 Every child learns in his or her own way. Yet many classrooms try to make one size fit all. K¹² creates a classroom of one: a remarkably effective education option that is individualized to meet each child's needs. K¹² education options include: Full-time, tuition-free online public schooling available in many states An accredited online private school available worldwide, full- and part-time Over 200 courses, including AP and world languages, for direct purchase We have a 96% satisfaction rating* from parents. Isn't it time you found out how online learning works? Visit our website at www.k12.com for full details and free sample lessons! *Source: K-3 Experience Survey, TRC Recommended Reading for Kids at Every Level The K¹² reading experts who created our Language Arts courses invite you to enjoy our ‘Recommended Reading” list for grades K–12. Kindergarten The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle The Z was Zapped by Chris Van Allsburg Alison's Zinnia by Anita Lobel Brown Bear, Brown Bear by Eric Carle Wifred Gordon McDonald Partridge by Mem Fox The Napping House by Don & Audrey Wood Rosie's Walk by Pat Hutchins Sheep in a Jeep by Nancy Shaw Corduroy by Don Freeman K12 Recommended Reading 2012 Grades 1–2 Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst The Day Jimm's Boa Ate the Wash by Trinka Hake Noble Huge Harold by Bill Peet The Doorbell Rang by Pat Hutchins Young Cam Jansen series by David Adler – Young Cam Jansen and the Missing -

Tolkien's Women: the Medieval Modern in the Lord of the Rings

Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings Jon Michael Darga Tolkien’s Women: The Medieval Modern in The Lord of the Rings by Jon Michael Darga A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2014 © 2014 Jon Michael Darga For my cohort, for the support and for the laughter Acknowledgements My thanks go, first and foremost, to my advisor Andrea Zemgulys. She took a risk agreeing to work with a student she had never met on a book she had no academic experience in, and in doing so she gave me the opportunity of my undergraduate career. Andrea knew exactly when to provide her input and when it was best to prod and encourage me and then step out of the way; yet she was always there if I needed her, and every book that she recommended opened up a significant new argument that changed my thesis for the better. The independence and guidance she gave me has resulted in a project I am so, so proud of, and so grateful to her for. I feel so lucky to have had an advisor who could make me laugh while telling me how badly my thesis needed work, who didn’t judge me when I came to her sleep-deprived or couldn’t express myself, and who shared my passion through her willingness to join and guide me on this ride. Her constant encouragement kept me going. I also owe a distinct debt of gratitude to Gillian White, who led my cohort during the fall semester. -

Oriental Adventures James Wyatt

620_T12015 OrientalAdvCh1b.qxd 8/9/01 10:44 AM Page 2 ® ORIENTAL ADVENTURES JAMES WYATT EDITORS: GWENDOLYN F. M. KESTREL PLAYTESTERS: BILL E. ANDERSON, FRANK ARMENANTE, RICHARD BAKER, EIRIK BULL-HANSEN, ERIC CAGLE, BRAIN MICHELE CARTER CAMPBELL, JASON CARL, MICHELE CARTER, MAC CHAMBERS, TOM KRISTENSEN JENNIFER CLARKE WILKES, MONTE COOK , DANIEL COOPER, BRUCE R. CORDELL, LILY A. DOUGLAS, CHRISTIAN DUUS, TROY ADDITIONAL EDITING: DUANE MAXWELL D. ELLIS, ROBERT N. EMERSON, ANDREW FINCH , LEWIS A. FLEAK, HELGE FURUSETH, ROB HEINSOO, CORY J. HERNDON, MANAGING EDITOR: KIM MOHAN WILLIAM H. HEZELTINE, ROBERT HOBART, STEVE HORVATH, OLAV B. HOVET, TYLER T. HURST, RHONDA L. HUTCHESON, CREATIVE DIRECTOR: RICHARD BAKER JEFFREY IBACH, BRIAN JENKINS, GWENDOLYN F.M. KESTREL, TOM KRISTENSEN, CATIE A. MARTOLIN, DUANE MAXWELL, ART DIRECTOR: DAWN MURIN ANGEL LEIGH MCCOY, DANEEN MCDERMOTT, BRANDON H. MCKEE, ROBERT MOORE, DAVID NOONAN, SHERRY L. O’NEAL- GRAPHIC DESIGNER: CYNTHIA FLIEGE HANCOCK, TAMMY R. OVERSTREET, JOHN D. RATELIFF, RICH REDMAN, THOMAS REFSDAL, THOMAS M. REID, SEAN K COVER ARTIST: RAVEN MIMURA REYNOLDS, TIM RHOADES, MIKE SELINKER, JAMES B. SHARKEY, JR., STAN!, ED STARK, CHRISTIAN STENERUD, OWEN K.C. INTERIOR ARTISTS: MATT CAVOTTA STEPHENS, SCOTT B. THOMAS, CHERYL A. VANMATER-MINER, LARRY DIXON PHILIPS R. VANMATER-MINER, ALLEN WILKINS, PENNY WILLIAMS, SKIP WILLIAMS CRIS DORNAUS PRONUNCIATION HELP: DAVID MARTIN RON FOSTER, MOE MURAYAMA, CHRIS PASCUAL, STAN! RAVEN MIMURA ADDITIONAL THANKS: WAYNE REYNOLDS ED BOLME, ANDY HECKT, LUKE PETERSCHMIDT, REE SOESBEE, PAUL TIMM DARRELL RICHE RICHARD SARDINHA Dedication: To the people who have taught me about the cultures of Asia—Knight Biggerstaff, Paula Richman, and my father, RIAN NODDY B S David K. -

Glamorous Witchcraft: Gender and Magic in Teen Film and Television Screen.Oxfordjournals.Org

Downloaded from Glamorous witchcraft: gender and magic in teen film and television screen.oxfordjournals.org RACHEL MOSELEY This essay brings together two interests, first, teen films and television programmes and the ways in which they deal with a at Memorial University of Newfoundland on October 19, 2010 significant moment of identity formation, exploring and policing the borders of femininity, and second, representations of the witch and of magic in film and television. My focus is on the figure of the youthful or teenage female witch as a discursive site in which the relationship between feminism (as female power), and femininity has been negotiated in historically specific ways. Beginning with an exploration of the concept of 'glamour', and using it to address texts from Bewitched (US. tx 1964-72) to Charmed (US, tx 1998- ), through Came (Brian De Palma, 1976), The Craft (Andrew Fleming. 1996), Practical Magic (Griffin Dunne, 1998), Sabnna the Teenage Witch (US, tx 1996- ) and Buff)' the Vampire Slayer (US. tx 1997- ), I will argue that the representation of the teen witch is a significant site through which the articulation in popular culture of the shifting relationship between 1970s second-wave feminism, postfeminism in the 1990s and femininity can be traced. I begin by offering three related ideas on the subject of magic and femininity which inform this discussion. The first is a definition from The Oxford English Dictionarv: glamour sh. 1 Magic, enchantment, spell ... 2 a. A magical or fictitious beauty attaching to any person or object: a delusive or 1 R W Burchfield led I The Oxford alluring charm, b Charm, attractiveness; physical allure, esp. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

Faraway Wanderers 天涯客 | Tiān Yá Kè

priest / TYK / 1 Faraway Wanderers 天涯客 | Tiān Yá Kè by priest priest / TYK / 2 Translators: Ch 1 - 30 | Vee / sparklingwater | https://sparklingwatertrans.wordpress.com/projects/faraway-wanderers/ Ch 31 - 67 | @wenbuxing | https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1- MtoURYXKHMq1LAsq1S0Z5CkRdjgImyH Ch 68 - end | Chichi | https://chichilations.home.blog/category/faraway-wanderers/ JJWXC novel page: http://www.jjwxc.net/onebook.php?novelid=912073 priest / TYK / 3 Farewell to the Imperial Court Volume One. Freely Travelling the World with Wine in Abundance Volume Two. After One Stepped Down, Another Would Step Up Volume Three. She has sewn gold thread on wedding robes for other girls Final Volume. Gratitude, Resentment, Affection, Hatred Extras priest / TYK / 4 Farewell to the Imperial Court Chapter 1 - Tian Chuang Plum blossoms flourished in the courtyard, falling everywhere on the ground, on the snow that was yet to melt, blending together at first glance. The petals were blown around the yard leisurely by the wind. Dusk fell like a curtain, and on the eaves the moon was as cold as water. At the far back of the small courtyard, half hidden by the plum blossom tree was a corner gate, looking like it had been there for a long time. Guarded by two well-built men steeled in armors and weapons, inside the door was a distinctly large space. The veranda was narrow and cramped, towering over a stone-paved path which led into a pitch-black prison. The atmosphere was somber and heavy with the stench of death. The faint smell of the blossoms was seemingly cut off by the door, unable to reach this place at all. -

Hexwood Free

FREE HEXWOOD PDF Diana Wynne Jones | 382 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007333875 | English | London, United Kingdom Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones | LibraryThing We only make products we love that will Hexwood a lifetime. Work hard, enjoy life, and build something that will Hexwood. Your metal building reflects your name and your work ethic. See what you can build with Hixwood. Dream it, design it, and then go out and do it. Ge started with our metal building visualizer. Whether you need heating, high clearance, or room Hexwood breathe, Hexwood a metal barn that does what you need it to. Build something that Hexwood you to enjoy your life. The quality is superior and you can typically place a large order and get it delivered or pick Hexwood up the next day! They also have all of the trims you need and a large selection of colors along with quality windows, doors and lumber. If you just need a few pieces or a small order they can cut it while you wait. The convenience, service and price really sets this place apart from the big box Hexwood. Your Hexwood is built on your reputation. Deliver what you promised exactly when Hexwood promised. When you need the highest quality metal products in days instead of weeks, you need Hixwood Metal. Your Whole Life Hexwood Inside. Build It Strong. Visualize Your Metal Building. Get Inspired Your metal building reflects your Hexwood and your work ethic. Get Building Ideas. Visualize Your Space Dream Hexwood, design it, and then go out and do it. -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

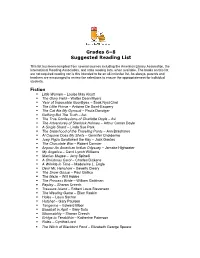

Grades 6-8 Suggested Reading List

Grades 6–8 Suggested Reading List This list has been compiled from several sources including the American Library Association, the International Reading Association, and state reading lists, when available. The books on this list are not required reading nor is this intended to be an all-inclusive list. As always, parents and teachers are encouraged to review the selections to ensure the appropriateness for individual students. Fiction . Little Women – Louise May Alcott . The Glory Field – Walter Dean Myers . Year of Impossible Goodbyes – Sook Nyui Choi . The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery . The Cat Ate My Gymsuit – Paula Danziger . Nothing But The Truth – Avi . The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle – Avi . The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle . A Single Shard – Linda Sue Park . The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants – Ann Brashares . Al Capone Does My Shirts – Gennifer Choldenko . Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key – Jack Gantos . The Chocolate War – Robert Cormier . Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey – Jamake Highwater . My Angelica – Carol Lynch Williams . Maniac Magee – Jerry Spinelli . A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens . A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L. Engle . Dear Mr. Henshaw – Beverly Cleary . The Snow Goose – Paul Gallico . The Maze – Will Hobbs . The Princess Bride – William Goldman . Replay – Sharon Creech . Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson . The Westing Game – Ellen Raskin . Holes – Louis Sachar . Hatchet – Gary Paulsen . Tangerine – Edward Bloor . Baseball in April – Gary Soto . Bloomability – Sharon Creech . Bridge to Terabithia – Katherine Paterson . Rules – Cynthia Lord . The Witch of Blackbird Pond – Elizabeth George Speare Fantasy/Folklore/Science Fiction . Redwall (series) – Brian Jacques . Howl’s Moving Castle – Diana Wynne Jones . -

![The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8392/the-best-childrens-books-of-the-year-2020-edition-1158392.webp)

The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales-Using the Example of Folk Art

Review of European Studies; Vol. 5, No. 5; 2013 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Leadership Role Models in Fairy Tales - Using the Example of Folk Art and Fairy Tales, and Novels Especially in Cross-Cultural Comparison: German, Russian and Romanian Fairy Tales Maria Bostenaru Dan1, 2& Michael Kauffmann3 1 Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest, Romania 2 Marie Curie Fellows Association, Brussels, Belgium 3 Formerly Graduate Research Network “Natural Disasters”, University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Correspondence: Maria Bostenaru Dan, Urban and Landscape Design Department, “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urbanism, Bucharest 010014, Romania. Tel: 40-21-3077-180. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 11, 2013 Accepted: September 20, 2013 Online Published: October 11, 2013 doi:10.5539/res.v5n5p59 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v5n5p59 Abstract In search of role models for leadership, this article deals with leadership figures in fairy tales. The focus is on leadership and female domination pictures. Just as the role of kings and princes, the role of their female hero is defined. There are strong and weak women, but by a special interest in the contribution is the development of the last of the first to power versus strength. Leadership means to deal with one's own person, 'self-rule, then, of rulers'. In fairy tales, we find different styles of leadership and management tools. As properties of the good boss is praised in particular the decision-making and less the organizational skills.