1 ABSTRACT William Sloane Coffin, One of the Most Influential And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

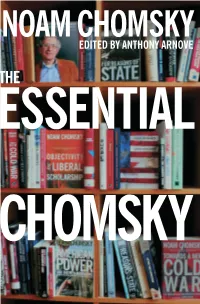

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 2-2-1968 Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968" (1968). Resist Newsletters. 4. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/4 a call to resist illegitimate authority .P2bruar.1 2 , 1~ 68 -763 Maasaohuaetta A.Tenue, RH• 4, Caabrid«e, Jlaaa. 02139-lfewaletter I 5 THE ARRAIGNMENTS: Boston, Jan. 28 and 29 Two days of activities surrounded the arraignment for resistance activity of Spock, Coffin, Goodman, Ferber and Raskin. On Sunday night an 'Interfaith Service for Consci entious Dissent' was held at the First Church of Boston. Attended by about 700 people, and addressed by clergymen of the various faiths, the service led up to a sermon on 'Vietnam and Dissent' by Rev. William Sloane Coffin. Later that night, at Northeastern University, the major event of the two days, a rally for the five indicted men, took place. An overflow crowd of more than 2200 attended the rally,vhich was sponsored by a broad spectrum of organizations. The long list of speakers included three of the 'Five' - Spock (whose warmth, spirit, youthfulness, and toughness clearly delight~d an understandably sympathetic and enthusiastic aud~ence), Coffin, Goodman. Dave Dellinger of Liberation Magazine and the National Mobilization Co11111ittee chaired the meeting. The other speakers were: Professor H. Stuart Hughes of Ha"ard, co-chairman of national SANE; Paul Lauter, national director of RESIST; Bill Hunt of the Boston Draft Resistance Group, standing in for a snow-bound liike Ferber; Bob Rosenthal of Harvard and RESIST who announced the formation of the Civil Liberties Legal Defense Fund; and Tom Hayden. -

A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

South Carolina Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2010 A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael Lonnie T. Brown Jr. University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lonnie T. Brown, Jr., A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael, 62 S. C. L. Rev. 1 (2010). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brown: A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Select A TALE OF PROSECUTORIAL INDISCRETION: RAMSEY CLARK AND THE SELECTIVE NON-PROSECUTION OF STOKELY CARMICHAEL LONNIE T. BROWN, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE PROTAGONISTS .................................................................................... 8 A. Ramsey Clark and His Civil Rights Pedigree ...................................... 8 B. Stokely Carmichael: "Hell no, we won't go!.................................. 11 III. RAMSEY CLARK'S REFUSAL TO PROSECUTE STOKELY CARMICHAEL ......... 18 A. Impetus Behind Callsfor Prosecution............................................... 18 B. Conspiracy to Incite a Riot.............................................................. -

Sanctuary: a Modern Legal Anachronism Dr

SANCTUARY: A MODERN LEGAL ANACHRONISM DR. MICHAEL J. DAVIDSON* The crowd saw him slide down the façade like a raindrop on a windowpane, run over to the executioner’s assistants with the swiftness of a cat, fell them both with his enormous fists, take the gypsy girl in one arm as easily as a child picking up a doll and rush into the church, holding her above his head and shouting in a formidable voice, “Sanctuary!”1 I. INTRODUCTION The ancient tradition of sanctuary is rooted in the power of a religious authority to grant protection, within an inviolable religious structure or area, to persons who fear for their life, limb, or liberty.2 Television has Copyright © 2014, Michael J. Davidson. * S.J.D. (Government Procurement Law), George Washington University School of Law, 2007; L.L.M. (Government Procurement Law), George Washington University School of Law, 1998; L.L.M. (Military Law), The Judge Advocate General’s School, 1994; J.D., College of William & Mary, 1988; B.S., U.S. Military Academy, 1982. The author is a retired Army judge advocate and is currently a federal attorney. He is the author of two books and over forty law review and legal practitioner articles. Any opinions expressed in this Article are those of the author and do not represent the position of any federal agency. 1 VICTOR HUGO, THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE-DAME 189 (Lowell Bair ed. & trans., Bantam Books 1956) (1831). 2 Michael Scott Feeley, Toward the Cathedral: Ancient Sanctuary Represented in the American Context, 27 SAN DIEGO L. REV. -

Page 1 of 5 Benjamin Spock Conspiracy 7/25/2009

Benjamin Spock Conspiracy Page 1 of 5 excerpt from It Did Happen Here by Bud and Ruth Schultz (University of California Press, 1989) The Conspiracy to Oppose the Vietnam War, Oral History of Benjamin Spock The Selective Service Act of 1948 made it a criminal offense for a person to knowingly counsel, aid, or abet someone in refusing or evading registration in the armed forces. In 1968, Dr. Benjamin Spock and four others were indicted for conspiring to violate this act. Evidence of the conspiracy was to be found in the public expressions of the defendants: hours of selectively edited newsreel footage of press conferences, demonstrations, and public addresses they made in opposition to government policy in Vietnam. What could better symbolize the damage such prosecutions made on the free marketplace of ideas? Why were they charged with conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet rather than with the commission of those acts themselves? Conspiracy, Judge Learned Hand said, is "the darling of the modern prosecutor's nursery."' It relaxes ordinary rules of evidence, frequently results in higher penalties than the substantive crime, may extend the statue of limitations, and holds all conspirators responsible for the acts of each. The conspirators may have acted entirely in the open, they may never have met; they may have agreed only implicitly; they may never have acted illegally. It's enough that they were of a like mind to do so. When applied to political activity, writing, and speech, a conspiracy charge has virtually no limits. Government attorneys could have included as co-conspirators the publishers of Dr. -

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Title Jessica Mitford Papers Dates: 1949-1973 Extent 67 document boxes, 3 note card boxes, 7 galley files, 1 oversize folder (27 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, printed material, reports, notes, interviews, manuscripts, legal documents, and other materials represent Jessica Mitford's work on her three investigatory books and comprise the bulk of these papers. Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Amanda McCallum, Jana Pellusch, 1990 Repository: Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Biographical Sketch Born September 11, 1917, in Batsford, Gloucestershire, England, Jessica Mitford is one of the six daughters of the Baron of Redesdale. The Mitfords are a well-known English family with a reputation for eccentricity. Of the Mitford sisters, Nancy achieved notoriety as a novelist and biographer. Diana married Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British fascists before World War II. Unity, also a fascist sympathizer, attempted suicide when Britain and Germany went to war. Deborah became the Duchess of Devonshire. Jessica, whose political bent ran opposite to that of her sisters, ran away to Loyalist Spain with her cousin, Esmond Romilly, during the Spanish Civil War. Jessica eventually married Romilly, who was killed during World War II. In 1943, Mitford married a labor lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, while working for the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. The couple soon moved to Oakland, California, where they joined the Communist Party. In California, Mitford worked as executive secretary for the Civil Rights Congress and taught sociology at San Jose State University. -

Union Collective

The magazine of Union Theological Seminary Spring 2019 UNION COLLECTIVE A More Plural Union At the Border Radical Legacy Black and Buddhist Union students and alums travel to Tijuana How James Cone’s work helped one Ga. Rima Vesely-Flad ’02, ’13 describes first-ever to protest U.S. abuse of migrants | p.2 town confront its racist past | p.4 gathering of Black Buddhist teachers | p.5 IN THIS ISSUE UNION COLLECTIVE Spring 2019 Published by Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York 3041 Broadway at 121st Street New York, NY 10027 TEL: 212-662-7100 WEB: utsnyc.edu Editor-in-Chief Emily Enders Odom ’90 Editorial Team Benjamin Perry ’15 Robin Reese Kate Sann EDS at union Writers 9 Emily Enders Odom ’90 Kelly Brown Douglas ’82, ’88 The Borders We Must Cross Simran Jeet Singh Dozens of Episcopal leaders visit the U.S. /Mexico border Serene Jones Pamela Ayo Yetunde Kenneth Claus ’70 Tom F. Driver ’53 articles Harmeet Kamboj ’20 Benjamin Perry ’15 LaGrange and the Lynching Tree 4 Lisa D. Rhodes Audrey Williamson Black and Buddhist 5 School of Sacred Music Alumni/ae Outliving Expectations 6 Copy Editor A More Plural Union 11 Eva Stimson Alumnae Receive Awards for Activism 20 Art Direction & Graphic Design Building a Legacy 25 Ron Hester Cover Photograph DEPARTMENTS Ron Hester 1 Letter from the President Back Cover Photographs 2 Union Making News Mohammad Mia ’21 9 Episcopal Divinity School at Union Highlights 15 Union Initiatives Stay Connected 18 Faculty News @unionseminary 21 Class Notes 23 In Memoriam 25 Giving Give to Union: utsnyc.edu/donate From the President Dear Friends, We are moving into a season of profound Union has long been a place that prepares change and spiritual renewal at Union people for ministry of all sorts, and while Theological Seminary. -

Theological Library Automation in 1995 196 Louis Charles Willard the Only Thing 217

The American Theological Library Association Essays in Celebration of the First Fifty Years Edited by M. Patrick Graham Valerie R. Hotchkiss Kenneth E. Rowe The American Theological Library Association 1996 Copyright © 1996 By The American Theological Library Association All rights reserved Published in the United States by The American Theological Library Association, .820 Church Street, Suite 300, Evanston, Illinois 60201 Prepress production, including text and cover, by Albert E. Hurd. ISBN: 0-524-10300-3 ATLA Cataloging in publication: The American Theological Library Association : essays in celebration of the first fifty years / edited by M. Patrick Graham, Valerie R. Hotchkiss and Kenneth E. Rowe. — Evanston, 111. : American Theological Library Association, 1996. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. Contents: ISBN 0-524-10300-3 1. American Theological Library Association. 2. Library science— Societies, etc. 3. Theological libraries. 4. Theology—Study and teaching. I. Graham, Matt Patrick. II. Hotchkiss, Valerie R., 1960- III. Theological Library Association׳ Rowe, Kenneth E. IV. American Z675.T4A62 1996 Printed on 50# Natural; an acid free paper by McNaughton & Gunn, Inc. Contents The Editors Acknowledgments v Albert E. Hurd Preface vil THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AMERICAN THEOLOGICAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Elmer J. and Betty A. O'Brien From Volunteerism to Corporate Professionalism: A Historical Sketch of the American Theological Library Association 3 John A. Bottler The Internationalization of the American Theological Library Association 25 Alan D. Krieger From the Outside In: A History of Roman Catholic Participation in the ATLA 36 Cindy Derrenbacker A Brief Reflection on ATLA Membership 43 Myron B. Chace ATLA's Preservation Microfilming Program: Growing Out of Our Work 47 Paul F. -

Benjamin Spock: a Two-Century Man

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 1996 Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man Bettye Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Bettye "Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man," The Courier 1996:5-21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S YRAC U SE UN IVE RS I TY LIB RA RY ASS 0 CI ATE S COURIER VOLUME XXXI . 1996 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXI Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man By Bettye Caldwell, Professor ofPediatrics, 5 Child Development, and Education, University ofArkansas for Medical Sciences While reviewing Benjamin Spock's pediatric career, his social activism, and his personal life, Caldwell assesses the impact ofthis "giant ofthe twentieth century" who has helped us to "prepare for the twenty-first." The Magic Toy Shop ByJean Daugherty, Public Affairs Programmer, 23 WTVH, Syracuse The creator ofThe Magic Thy Shop, a long-running, local television show for children, tells how the show came about. Ernest Hemingway By ShirleyJackson 33 Introduction: ShirleyJackson on Ernest Hemingway: A Recovered Term Paper ByJohn W Crowley, Professor ofEnglish, Syracuse University For a 1940 English class at Syracuse University, ShirleyJackson wrote a paper on Ernest Hemingway. Crowley's description ofher world -

Proquest Dissertations

GIVING SCRIPTURE ITS VOICE: THE TENSIVE IMPERTINENCE OF THE LITERAL SENSE OF THE PERICOPE, METAPHORICAL MEANING-MAKING, AND PREACHING THE WORD OF GOD. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF EMMANUEL COLLEGE AND THE PASTORAL DEPARTMENT OF THE TORONTO SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY AWARDED BY EMMANUEL COLLEGE OF VICTORIA UNIVERSITY AND THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. BY HENRY JOHN LANGKNECHT COLUMBUS, OHIO APRIL 2008 © HENRY J. LANGKNECHT, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41512-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41512-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Urban Ministry Reconsidered Contexts and Approaches

Urban Ministry Reconsidered Contexts and Approaches Edited by R. Drew Smith, Stephanie C. Boddie, and Ronald E. Peters Contents Introduction 1 R. Drew Smith I. Urban Conceptual Worldviews 1. Urban Conceptualizing in Historical Perspective 15 Ronald E. Peters 2. The New Urbanism and Its Challenge to the Church 21 Michael A. Mata 3. The City’s Grace 28 Peter Choi 4. Toward a Missiological Turn in Urban Ministry 35 Scott Hagley 5. Urban Ministry as the New Frontier? 44 Felicia Howell LaBoy 6. Urban Ministry as Incarnational 54 Kang-Yup Na 7. Religion and Race in Urban Spaces across Africa and the Diaspora 62 William Ackah 8. Wholeness and Human Flourishing as Guideposts for Urban Ministry 70 Lisa Slayton and Herb Kolbe vi Contents II. Urban Community Formation 9. Low-Income Residents and Religious In-Betweenness in the United States and South Africa 79 R. Drew Smith 10. Racial Equity and Faith-Based Organizing at Community Renewal Society 89 Curtiss Paul DeYoung 11. Ferguson Lessons about Church Solidarity with Communities of Struggle 97 Michael McBride 12. Listening, Undergirding, and Cross-Sector Community Building 104 Kimberly Gonxhe 13. Internal Dimensions of Church Connectedness to Community 109 Randall K. Bush 14. Prison Ministry with Women and Girls of African Descent 115 Angelique Walker-Smith 15. Christian Community Responses to African Immigrants in the United States 122 Laurel E. Scott 16. Theological Professionals, the Community, and Overcoming the Disconnection 131 Anthony Rivera 17. Theological Pedagogies and Urban Change-Making in an African City 138 Stephan de Beer III. Urban Social Policy 18. Church Pursuits of Economic Justice, Public Health, and Racial Equity 149 John C. -

PHS News August 2015

PHS News August 2015 University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut. PHS News Perhaps surprisingly given the prominence August 2015 of religion and faith to inspire peacemakers, this is the first PHS conference with its main theme on the nexus of religion and peace. The conference theme has generated a lot of interest from historians and scholars in other disciplines, including political science and religious studies. We are expecting scholars and peacemakers from around the globe in attendance: from Australia, Russia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Germany and Costa Rica. Panel topics include the American Catholic peace movement with commentary by Jon Cornell, religion and the struggle against Boko Newsletter of the Haram, and religion and the pursuit of peace Peace History Society in global contexts and many others. www.peacehistorysociety.org Our keynote speaker, Dr. Leilah Danielson, President’s Letter Associate Professor of History at Northern Arizona University, will speak directly to the larger conference themes and will reflect By Kevin J. Callahan PHS’s interdisciplinary approach. Dr. Danielson’s book, American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the 20th Century (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), examines the evolving political and religious thought of A.J. Muste, a leader of the U.S. left. For the full conference program, see pages 9-14! Make plans now to attend the conference in Connecticut in October! Greetings Peace History Society Members! We will continue our tradition of announcing the winners of the Scott Bills On behalf of the entire PHS board and Memorial Prize (for a recent book on peace executive officers, it is our honor to serve history), the Charles DeBenedetti Prize (for PHS in 2015 and 2016.