An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Evolution of Grasping and Manipulation Emmanuelle Pouydebat, Ameline Bardo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracy L. Kivell Pierre Lemelin Brian G. Richmond Daniel Schmitt Editors

Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor: Louise Barrett Tracy L. Kivell Pierre Lemelin Brian G. Richmond Daniel Schmitt Editors The Evolution of the Primate Hand Anatomical, Developmental, Functional, and Paleontological Evidence Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor Louise Barrett Lethbridge , Alberta , Canada More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/5852 Tracy L. Kivell • Pierre Lemelin Brian G. Richmond • Daniel Schmitt Editors The Evolution of the Primate Hand Anatomical, Developmental, Functional, and Paleontological Evidence Editors Tracy L. Kivell Pierre Lemelin Animal Postcranial Evolution (APE) Lab Division of Anatomy Skeletal Biology Research Centre Department of Surgery School of Anthropology and Conservation Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Kent University of Alberta Canterbury, UK Edmonton , AB , Canada Department of Human Evolution Daniel Schmitt Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Anthropology Duke University Leipzig , Germany Durham , NC , USA Brian G. Richmond Division of Anthropology American Museum of Natural History New York , NY , USA Department of Human Evolution Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Leipzig, Germany ISSN 1574-3489 ISSN 1574-3497 (electronic) Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects ISBN 978-1-4939-3644-1 ISBN 978-1-4939-3646-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-3646-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016935857 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Original Unedited Manuscript

Regional patterning in tail vertebral form and function in chameleons (C. calyptratus) Allison M. Luger1, Peter J. Watson2, Hugo Dutel3,2, Michael J. Fagan2, Luc Van Hoorebeke4, Anthony Herrel1,5, Dominique Adriaens1 1 Evolutionary Morphology of Vertebrates, Ghent University, Belgium 2 Department of Engineering, University of Hull, UK 3. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK 4 UGCT - Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ghent University, Proeftuinstraat 86/N12, 9000 Gent, Belgium Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/advance-article/doi/10.1093/icb/icab125/6296421 by guest on 15 June 2021 5 UMR 7179 MECADEV, C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., Département Adaptations du Vivant, Bâtiment d'Anatomie Comparée, 55 rue Buffon, 75005, Paris, France ORCID: 0000-0003-0991-4434 Corresponding author : Allison M. Luger K.L. Ledeganckstraat 30 9000 Ghent, Belgium E-mail : [email protected] Tel : +32 484153535 Running title : Tail vertebral form affects prehensility Total number of words: 5781 ORIGINAL UNEDITED MANUSCRIPT © The Author(s) 2021. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Previous studies have focused on documenting shape variation in the caudal vertebrae in chameleons underlying prehensile tail function. The goal of this study was to test the impact of this variation on tail function using multibody dynamic analysis (MDA). First, observations from dissections and 3D reconstructions generated from contrast- enhanced µCT-scans were used to document regional variation in arrangement of the caudal muscles along the antero-posterior axis. -

Is Variation in Tail Vertebral Morphology Linked to Habitat Use in Chameleons?

Received: 10 September 2019 Revised: 3 December 2019 Accepted: 12 December 2019 DOI: 10.1002/jmor.21093 RESEARCH ARTICLE Is variation in tail vertebral morphology linked to habitat use in chameleons? Allison M. Luger1 | Anouk Ollevier1 | Barbara De Kegel1 | Anthony Herrel1,2 | Dominique Adriaens1 1Department of Evolutionary Biology of Vertebrates, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Abstract 2Département Adaptations du Vivant, Chameleons (Chamaeleonidae) are known for their arboreal lifestyle, in which they Bâtiment d'Anatomie Comparée, UMR 7179 make use of their prehensile tail. Yet, some species have a more terrestrial lifestyle, C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N, Paris, France such as Brookesia and Rieppeleon species, as well as some chameleons of the genera Correspondence Chamaeleo and Bradypodion. The main goal of this study was to identify the key ana- Allison M. Luger, Department of Evolutionary Biology of Vertebrates, Ghent University, tomical features of the tail vertebral morphology associated with prehensile capacity. K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35, 9000 Ghent, Belgium. Both interspecific and intra-individual variation in skeletal tail morphology was inves- Email: [email protected] tigated. For this, a 3D-shape analysis was performed on vertebral morphology using Funding information μCT-images of different species of prehensile and nonprehensile tailed chameleons. Tournesol Mobility Grant; FWO, Grant/Award Number: #3G006716 A difference in overall tail size and caudal vertebral morphology does exist between prehensile and nonprehensile taxa. Nonprehensile tailed species have a shorter tail with fewer vertebrae, a generally shorter neural spine and shorter transverse pro- cesses that are positioned more anteriorly (with respect to the vertebral center). The longer tails of prehensile species have more vertebrae as well as an increased length of the processes, likely providing a greater area for muscle attachment. -

Foraging Behaviour of the Slender Loris (Loris Lydekkerianus Lydekkerianus): Implications for Theories of Primate Origins

Journal of Human Evolution 49 (2005) 289e300 Foraging behaviour of the slender loris (Loris lydekkerianus lydekkerianus): implications for theories of primate origins K.A.I. Nekaris* Department of Anthropology, Washington University, Campus Box 1114, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA Received 3 May 2004; accepted 18 April 2005 Abstract Members of the Order Primates are characterised by a wide overlap of visual fields or optic convergence. It has been proposed that exploitation of either insects or angiosperm products in the terminal branches of trees, and the corresponding complex, three-dimensional environment associated with these foraging strategies, account for visual convergence. Although slender lorises (Loris sp.) are the most visually convergent of all the primates, very little is known about their feeding ecology. This study, carried out over 10 ½ months in South India, examines the feeding behaviour of L. lydekkerianus lydekkerianus in relation to hypotheses regarding visual predation of insects. Of 1238 feeding observations, 96% were of animal prey. Lorises showed an equal and overwhelming preference for terminal and middle branch feeding, using the undergrowth and trunk rarely. The type of prey caught on terminal branches (Lepidoptera, Odonata, Homoptera) differed significantly from those caught on middle branches (Hymenoptera, Coleoptera). A two-handed catch accompanied by bipedal postures was used almost exclusively on terminal branches where mobile prey was caught, whereas the more common capture technique of one-handed grab was used more often on sturdy middle branches to obtain slow moving prey. Although prey was detected with senses other than vision, vision was the key sense used upon the final strike. -

Adaptive Simplification and the Evolution of Gecko Locomotion: Morphological and Biomechanical Consequences of Losing Adhesion

Adaptive simplification and the evolution of gecko locomotion: Morphological and biomechanical consequences of losing adhesion Timothy E. Highama,1, Aleksandra V. Birn-Jefferya, Clint E. Collinsa, C. Darrin Hulseyb, and Anthony P. Russellc aDepartment of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of New Orleans, New Orleans, LA 70148; and cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4 Edited by David B. Wake, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved November 26, 2014 (received for review October 1, 2014) Innovations permit the diversification of lineages, but they may also would be appropriate to investigate the resulting changes and impose functional constraints on behaviors such as locomotion. trade-offs that occur during evolutionary reduction and functional Thus, it is not surprising that secondary simplification of novel loco- loss within a clade that displays a spectrum of changes in a highly motory traits has occurred several times among vertebrates and functional anatomical complex. could potentially lead to exceptional divergence when constraints The gekkotan adhesive system has been instrumental in en- are relaxed. For example, the gecko adhesive system is a remarkable abling these lizards to occupy otherwise inaccessible regions of the innovation that permits locomotion on surfaces unavailable to locomotor habitat by enhancing climbing effectiveness through other animals, but has been lost or simplified in species -

7 Trochlear Waisting

Durham E-Theses The extent of homoplasy in the trunk and forelimb of the hominoidea Worthington, Steven How to cite: Worthington, Steven (2002) The extent of homoplasy in the trunk and forelimb of the hominoidea, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4095/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The Extent of HomopBasy in the Trunk and Forelimb of the Hominoidea A Thesis presented by Steven Worth engton to The Graduate School For the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Anthropology 2 9 JAN 2003 Department of Anthropology University of Durham June 2002 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Declaration This thesis is the result of my own work, and no part of it has previously been submitted for a degree at any university. -

Sinclair Lewis

SATIRE OF CHARACTERIZATION IN THE FICTION OF SINCLAIR LEWIS by SUE SIMPSON PARK, B.A. , M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Technological College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairman of the Committee &l^ 1? }n^ci./A^.Q^ Accepted <^ Dean of the Gradu^e SiChool May, 196( (\^ '.-O'p go I 9U I am deeply indebted to Professor Everett A. Gillis for his direction of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee, Professors J. T. McCullen, Jr., and William E. Oden, for their helpful criticism. I would like to express my gratitude, too, to my husband and my daughter, without whose help and encouragement this work would never have been completed. LL CONTENTS I. SINCLAIR LEWIS AND DRAMATIC SATIRE 1 II. THE WORLD OF THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY 33 III. THE PHYSICIAN AND HIS TASK 68 IV. THE ARTIST IN THE AMERICAN MILIEU 99 V. THE DOMESTIC SCENE: WIVES AND MARRIAGE ... 117 VI. THE AMERICAN PRIEST 152 NOTES ^76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 131 ILL CHAPTER I SINCLAIR LEWIS AND DRAMATIC SATIRE In 1930 Sinclair Lewis was probably the most famous American novelist of the time; and that fame without doubt rested, as much as on anything else, on the devastating satire of the American scene contained in his fictional portrayal of the inhabitants of the Gopher Prairies and the Zeniths of the United States. As a satirist, Lewis perhaps ranks with the best--somewhere not far below the great masters of satire, such as Swift and Voltaire. -

From Evolutionary Morphology of Prehensile Tails in Syngnathid Fishes to Exploring Bio-Inspiration Potentials

TRANSFORMING TAILS INTO TOOLS: FROM EVOLUTIONARY MORPHOLOGY OF PREHENSILE TAILS IN SYNGNATHID FISHES TO EXPLORING BIO-INSPIRATION POTENTIALS CÉLINE NEUTENS Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Academic year 2015-2016 Doctor in Sciences (Biology) Rector: Prof. Dr. Anne De Paepe Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het Dean: Prof. Dr. Herwig Dejonghe bekomen van de graad van Promotor: Prof. Dr. Dominique Adriaens Doctor in de Wetenschappen (Biologie) Co-promotor: Prof. Dr. Ir. Matthieu De Beule © All rights reserved. This thesis contains confidential information and confidential research results that are property to the UGent (Research group Evolutionary Morphology of Vertebrates, Department of Biology). The contents of this thesis may under no circumstances be made public, nor complete or partial, without the explicit and preceding permission of the UGent representative, i.e. the supervisor. The thesis may under no circumstances be copied or duplicated in any form, unless permission granted in written form. Any violation of the confidential nature of this thesis may impose irreparable damage to the UGent. In case of a dispute that may arise within the context of this declaration, the Judicial Court of Gent only is competent to be notified. © Cover photograph: Art Wolfe Examination Committee Prof. Dr. Dominique Adriaens (Promotor) (Ghent University, Belgium) Prof. Dr. Ir. Matthieu De Beule (Co-promotor) (Ghent University, Belgium) Prof. Dr. Ann Huysseune (Chair) (Ghent University, Belgium) Dr. Sam Van Wassenbergh (Secretary) (CNRS, France) Prof. Dr. Anthony Herrel (Ghent University, Belgium; CNRS, France) Prof. Dr. Peter Aerts (Antwerp University, Belgium) Prof. Dr. Ir. Michael Porter (Clemson University, U.S.A.) Prof. Dr. Ir. Benedict Verhegghe (Ghent University, Belgium) Dr. -

Do Substrate Type and Gap Distance Impact Gap-Bridging Strategies in Arboreal 2 Chameleons? 3 4 Running Title: Prehensile Tail Use Chameleons

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Do substrate type and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal 2 chameleons? 3 4 Running title: Prehensile tail use chameleons 5 Authors: Allison M. Luger1, Vincent Vermeylen1, Anthony Herrel1,2, Dominique Adriaens1 6 1: Ghent University, Evolutionary Morphology of Vertebrates. K.L. Ledeganckstraat 35, 9000 7 Ghent, Belgium. 8 2 : UMR 7179 C.N.R.S/M.N.H.N., Département Adaptations du Vivant, Bâtiment d'Anatomie 9 Comparée, 55 rue Buffon, 75005, Paris, France. 10 Corresponding author: Allison M. Luger: [email protected] 11 Keywords: Chameleons, Prehensility, gap bridging, substrate type 12 Summary statement 13 Chameleons use their prehensile tail more often when crossing greater distances and switch 14 strategies on when and how they use their tails. Males are able to cross relatively greater 15 distances than females. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 16 Abstract 17 Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, having zygodactylous hands and feet as 18 well as a fully prehensile tail. -

Do Substrate Roughness and Gap Distance Impact Gap-Bridging Strategies in Arboreal Chameleons

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21.260596; this version posted December 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. RESEARCH ARTICLE Do substrate roughness and gap distance impact gap-bridging strategies in arboreal chameleons Luger Allison M.1, Vermeylen Vincent1, Herrel Anthony2, Adriaens Dominique1 1 Ghent University, Evolutionary Morphology of Vertebrates – Ghent, Belgium 2 C.N.R.S./M.N.H.N. Département Adaptations du Vivant, Bâtiment d’Anatomie Comparée – Paris, France Cite as: Luger, A.M., Vermeylen, V., This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Herrel, A. and Adriaens, D. (2020) Do substrate roughness and gap Peer Community in Zoology distance impact gap-bridging doi: https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.zool.100005 strategies in arboreal chameleons? bioRxiv, 2020.08.21.260596, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Zoology. doi: ABSTRACT https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.21. 260596 Chameleons are well-equipped for an arboreal lifestyle, havinving ‘zygodactylous’ hands and feet as well as a fully prehensile tatail. However, to what degree tail use is preferred over autopod prehensiosion has been largely neglected. Using an indoor experimental set-upu , Posted: 10-11-2020 where chameleons had to cross gaps of varying distances, we teststed the effect of substrate diameter and roughness on tail use in Chamaeleo calyptratus. Our results show that when crossing greatater Recommender: Ellen Decaestecker distances, C. -

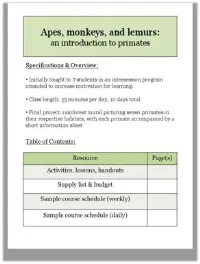

Introduction to Primates

Index of activities, lessons, and hand-outs The following handouts/documents are included in PDF format and are ordered by type. “Day in Schedule” refers to the schedule of the two-week pilot course, but timing may be adjusted to as needed. Resource Type Page Numbers Organizational (e.g. classroom routines, rules, final project) Notes Activities Handout/Document Description Version Activity/Lesson Day in Page schedule # Class routines Class routines; addresses entering Teacher Organizational Day 1 classroom, picking volunteers, etc. Gorilla troop rules Class rule sheet in the context of Student Organizational Day 1 gorilla society Gorilla troop rules Student version plus notes Teacher Organizational Day 1 Table of contents For student binders, to be updated as Student Organizational Day 1 course proceeds. Teacher should create master copy as well. Course survey What do students already know, and Student Organizational Days 1, 9 what have they learned? To be completed on the first day of class and at the end of the course. Course survey Student version plus answers Teacher Organizational Days 1, 9 End-of-class reflection Topic of reflection may vary, but Student Organizational Introduced typically a chance for students to write Day 1; used what they learned. daily Mural description Run-down of the mural project Teacher Organizational Day 1 Activity 1: Practice Introduction to the scientific method Teacher Activity 1: Practice Day 1 being a scientist! (in the context of primates) being a scientist! What is a primate? (I) Focus on mammal aspect and the two Student Notes Day 2 main groups of primates. Useful in conjunction with primate family tree. -

Goal-Directed Tail Use in Colombian Spider Monkeys (Ateles Fusciceps Rufiventris) Is Highly Lateralized

Journal of Comparative Psychology © 2017 American Psychological Association 2018, Vol. 132, No. 1, 40–47 0735-7036/18/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000094 Goal-Directed Tail Use in Colombian Spider Monkeys (Ateles fusciceps rufiventris) Is Highly Lateralized Eliza L. Nelson and Giulianna A. Kendall Florida International University Behavioral laterality refers to a bias in the use of one side of the body over the other and is commonly studied in paired organs (e.g., hands, feet, eyes, antennae). Less common are reports of laterality in unpaired organs (e.g., trunk, tongue, tail). The goal of the current study was to examine tail use biases across different tasks in the Colombian spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps rufiventris) for the first time (N ϭ 14). We hypothesized that task context and task complexity influence tail laterality in spider monkeys, and we predicted that monkeys would exhibit strong preferences for using the tail for manipulation to solve out-of-reach feeding problems, but not for using the tail at rest. Our results show that a subset of spider monkeys solved each of the experimental problems through goal-directed tail use (N ϭ 7). However, some tasks were more difficult than others, given the number of monkeys who solved the tasks. Our results supported our predictions regarding laterality in tail use and only partially replicated prior work on tail use preferences in Geoffroy’s spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). Overall, skilled tail use, but not resting tail use, was highly lateralized in Colombian spider monkeys. Keywords: laterality, hemispheric specialization, spider monkey, tail use Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/com0000094.supp Behavioral laterality refers to a bias in the use of one side of the spheres may streamline neural processing and, therefore, have body over the other and is commonly studied in paired organs downstream advantages on behavior (Rogers & Vallortigara, 2015; (e.g., hands, feet, eyes, antennae).