Outlines of Criminal Iaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

CHAPTER 10 General Offenses

CHAPTER 10 General Offenses Article I Offenses and Miscellaneous Provisions Sec. 10-1 Definitions generally Sec. 10-2 Legislative intent Sec. 10-3 Affirmative defenses Sec. 10-4 Penalty Sec. 10-5 Parental responsibility for acts of minor children Sec. 10-6 Attempts; aiding, abetting or advising Sec. 10-7 Accessory to crime Article II Property Sec. 10-21 Trespass Sec. 10-22 Interference with use of public property Sec. 10-23 Parking on private premises Sec. 10-24 Littering Article III Damage or Destruction Sec. 10-41 Public property generally Sec. 10-42 Criminal mischief Sec. 10-43 Posters Article IV Theft and Related Offenses Sec. 10-61 Theft generally Sec. 10-62 Bad checks Sec. 10-63 Theft of rental property Sec. 10-64 Joyriding Sec. 10-65 Shoplifting Sec. 10-66 Price switching Sec. 10-67 Theft by receiving Sec. 10-68 Questioning of person suspected of theft without liability Article V Public Health and Safety Sec. 10-81 Abandoned containers Sec. 10-82 Storage of flammable liquids in vehicles Sec. 10-83 Storage of construction materials Sec. 10-84 Contamination of water Sec. 10-85 Poisonous substances Sec. 10-86 Cruelty to animals Sec. 10-87 Hunting and feeding of wildlife prohibited Sec. 10-88 Fire bans Article VI Morals Sec. 10-101 Lewd conduct Sec. 10-102 Obscene conduct Sec. 10-103 Indecent books or demonstrations Article VII Public Peace Sec. 10-121 Disorderly conduct Sec. 10-122 Disrupting lawful assembly Sec. 10-123 Loitering Sec. 10-124 Unlawful assembly Sec. 10-125 Unlawful interference; educational institutions 10-1 Sec. -

Suppression of Popular Gatherings in England, 1800-1830 Frank W

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 1981 Suppression of Popular Gatherings in England, 1800-1830 Frank W. Munger New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Judges Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation 25 Am. J. Legal Hist. 111 (1981) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Suppression of Popular Gatherings in England, 1800-1830 by FRANK MUNGER* Recent works on crime and society in eighteenth century England have reported challenging questions about the exercise of legal authority and the maintenance of control over the working classes.1 It has been suggested, for example, that the manipulation of sentencing for capital offenses at eighteenth century assizes re- flected a deep concern for maintaining the legitimacy of class rule through the legal system apart from any immediate concern with crime. 2 It has also been argued that while the creation of capital offenses under the Black Act of 1722 reflected class struggle over the uses of property, the commitment of the English legal system to even-handed justice tempered the effect of the Act in certain in- stances. 3 Thus, by two different routes, recent historians have ar- gued that the English criminal justice system produced more temp- erate and "just" results than the context of class rule might suggest. Such studies suggest that a legal system, and specifically the legal system of Industrial Revolution England, was a complex sys- tem. -

5 Freedom of Association and Assembly

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Brunel University Research Archive 5 Freedom of Association and Assembly RODA MUSHKAT S.K. LAU, perhaps the most perceptive academic observer of the Hong Kong social scene, has contended in his influential book1 that the dominant cultural code in the territory is 'utilitarianistic familism'. This manifests itself in a normative and behavioural tendency of local Chinese to place their familial interests above the interests of other individuals, groups, and society as a whole, and to structure their relationships with other parties in a manner consistent with the ultimate objective of maximizing familial wel fare. The utilitarianistic dimension of familism is rooted, accord ing to Lau, in the strong inclination exhibited by family members to accord far greater importance to material interests than to non-material ones. Utilitarianistic familism is said to generate attitudes such as 'aloofness towards society' ('[t]he Hong Kong Chinese in general neither identify with Hong Kong nor are committed to it but rather tend to treat it as an instrument. Consequently, society is conceived as a setting wherein one exploits ... the opportunities available ... to advance the interests of oneself and one's fami lial group');2 'avoidance of involvement with outsiders' ('[s]uspi- cious attitudes towards outsiders and distrust of them have long been a recognized cultural feature of Chinese people, which have their roots in a peasant society where relatively self-contained life confined to small geographical areas was the rule. Given the Chinese abhorrence of conflict and aggression, we find the coexistence of intense emotional attachment among people in small groups, and cold impersonal postures towards those who are outsiders .. -

Law of Crimes (Indian Penal Code)

Class –LL.B (HONS.) II SEM. Subject – IPC LAW OF CRIMES (INDIAN PENAL CODE) LLLL UNIT-III Group liability 1. Common Intention 2. Abetment UNIT-I General 3. Instigation, aiding and conspiracy 1. Concept of crime UNIT-II Element of Criminal 4. Mere act of abetment punishable 2. Distinction between crime Liability 5. Unlawful assembly and other wrongs 1. Person definition - natural 6. Basis of liability 3. McCauley’s draft based and legal person 7. Criminal conspiracy essentially on British notions 2. Mens rea- evil intention 8. Rioting as a specific offence 4. Salient features of the 3. Recent trends to fix liability General Exceptions : I.P.C. without mens rea in certain 9. Mental incapacity 5. IPC: a reflection of socio- economic offences 10. Minority different 4. Act in furtherance of guilty 11. Insanity social and moral values intent- common object 12. Medical and legal insanity 6. Applicability of I.P.C.- 5. Factors negativing guilty 13. Intoxication intention territorial and personal 14. Private defence-justification and limits 6. Definition of specific terms 15. When private defence extends to causing of death to protect body and property 16. Necessity 17. Mistake of fact 18. Offence relating to state 19. Against Tranquility 20. Contempt of Lawful Authority UNIT-IV Offences against human body 1. Culpable homicide 2. Murder 3. Culpable homicide amounting to murder 4. Grave and sudden provocation Unit-V Types of Punishment 5. Exceeding right to private defence 1. Death PAPER-III LAW OF CRIMES6. Hurt - grievous-I (PENAL and simple CODE) 2. Social relevance of capital punishment UNIT-I General 7. -

Cap. 16 Tanzania Penal Code Chapter 16 of the Laws

CAP. 16 TANZANIA PENAL CODE CHAPTER 16 OF THE LAWS (REVISED) (PRINCIPAL LEGISLATION) [Issued Under Cap. 1, s. 18] 1981 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, DARES SALAAM Penal Code [CAP. 16 CHAPTER 16 PENAL CODE Arrangement of Sections PARTI General Provisions CHAPTER I Preliminary 1. Short title. 2. Its operation in lieu of the Indian Penal Code. 3. Saving of certain laws. CHAPTER II Interpretation 4. General rule of construction. 5. Interpretation. CHAPTER III Territorial Application of Code 6. Extent of jurisdiction of local courts. 7. Offences committed partly within and partly beyond the jurisdiction, CHAPTER IV General Rules as to Criminal Responsibility 8. Ignorance of law. 9. Bona fide claim of right. 10. Intention and motive. 11. Mistake of fact. 12. Presumption of sanity^ 13. Insanity. 14. Intoxication. 15. Immature age. 16. Judicial officers. 17. Compulsion. 18. Defence of person or property. 18A. The right of defence. 18B. Use of force in defence. 18C. When the right of defence extends to causing abath. 19. Use of force in effecting arrest. 20. Compulsion by husband. 21. Persons not to be punished twice for the same offence. 4 CAP. 16] Penal Code CHAPTER V Parties to Offences 22. Principal offenders. 23. Joint offences. 24. Councelling to commit an offence. CHAPTER VI Punishments 25. Different kinds of punishment. 26. Sentence of death. 27: Imprisonment. 28. Corpora] punishment. 29. Fines. 30. Forfeiture. 31. Compensation. 32. Costs. 33. Security for keeping the peace. 34. [Repealed]. 35. General punishment for misdemeanours. 36. Sentences cumulative, unless otherwise ordered. 37. Escaped convicts to serve unexpired sentences when recap- 38. -

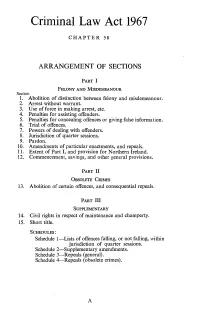

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

THE COMMON LAW in INDIA AUSTRALIA the Law Book Co

THE HAMLYN LECTURES TWELFTH SERIES THE COMMON LAW IN INDIA AUSTRALIA The Law Book Co. of Australasia Pty Ltd. Sydney : Melbourne : Brisbane CANADA AND U.S.A. The Carswell Company Ltd. Toronto INDIA N. M. Tripathi Private Ltd. Bombay NEW ZEALAND Sweet & Maxwell (N.Z.) Ltd. Wellington PAKISTAN Pakistan Law House Karachi The Common Law in India BY M. C. SETALVAD, Padma Vibhufhan, Attorney-General of India Published under the auspices of THE HAMLYN TRUST LONDON STEVENS & SONS LIMITED I960 First published in I960 by Stevens & Sons Limited of 11 New Fetter Lane in the City of London and printed in Great Britain by The Eastern Press Ltd. of London and Reading Stevens & Sons, Limited, London 1960 CONTENTS The Hamlyn Trust ----- page vii 1. RISE OF THE COMMON LAW 1 2. CIVIL LAW -------63 3. CRIMINAL LAW ------ us 4. THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION - - - - 168 EPILOGUE 224 HAMLYN LECTURERS 1949 The Right Hon. Lord Denning 1950 Richard O'Sullivan, Q.C. 1951 F. H. Lawson, D.C.L. 1952 A. L. Goodhart, K.B.E., Q.C, F.B.A. 1953 Sir Carleton Kemp Allen, Q.C, F.B.A. 1954 C. J. Hamson, M.A., LL.M. 1955 Glanville Williams, LL.D. 1956 The Hon. Sir Patrick Devlin 1957 The Right Hon. Lord MacDermott 1958 Sir David Hughes Parry, Q.C, M.A., LL.D., D.C.L. 1959 C. H. S. Fifoot, M.A., F.B.A. 1960 M. C. Setalvad, Padma Vibhufhan VI THE HAMLYN TRUST THE Hamlyn Trust came into existence under the will of the late Miss Emma Warburton Hamlyn, of Torquay, who died in 1941, aged eighty. -

Administration of Justice Act 1970

Status: Point in time view as at 03/04/2006. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Administration of Justice Act 1970. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Administration of Justice Act 1970 1970 CHAPTER 31 An Act to make further provision about the courts (including assizes), their business, jurisdiction and procedure; to enable a High Court judge to accept appointment as arbitrator or umpire under an arbitration agreement; to amend the law respecting the enforcement of debt and other liabilities; to amend section 106 of the Rent Act 1968; and for miscellaneous purposes connected with the administration of justice. [29th May 1970] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 By Criminal Justice Act 1991 (c. 53, SIF 39:1), s. 101(1), Sch. 12 para.23; S.I. 1991/2208, art. 2(1), Sch.1 it is provided (14.10.1991) that in relation to any time before the commencement of s. 70 of that 1991 Act (which came into force on 1.10.1992 by S.I. 1992/333, art. 2(2), Sch. 2) references in any enactment amended by that 1991 Act, to youth courts shall be construed as references to juvenile courts. Commencement Information I1 Act not in force at Royal Assent see s. 54(4); Act wholly in force 1.10.1971 PART I COURTS AND JUDGES High Court 1 Redistribution of business among divisions of the High Court. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1 Combating Public Disorder SPONSOR(S)

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: HB 1 Combating Public Disorder SPONSOR(S): Fernandez-Barquin and others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM. BILLS: SB 484 REFERENCE ACTION ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR or BUDGET/POLICY CHIEF 1) Criminal Justice & Public Safety Subcommittee 11 Y, 6 N Hall Hall 2) Justice Appropriations Subcommittee 10 Y, 5 N Jones Keith 3) Judiciary Committee SUMMARY ANALYSIS Over the past year, protests relating to race, police tactics, and politics have swept across the country. While many protests in Florida remained peaceful, some cities were forced to issue emergency curfews as police officers were injured and local businesses were damaged and burglarized. Most recently, the Governor activated the National Guard to assist in securing the Capitol after authorities warned of threats of violent protests. While some violent and disorderly behavior associated with rioting may be prosecuted under current law, prosecuting and preventing other violent and destructive conduct may be difficult. HB 1 gives law enforcement and prosecutors additional tools to prevent violence and property destruction and to hold any person who uses a protest as an opportunity to commit crime accountable for their actions. The bill: Defines previously undefined crimes of affray, rioting, and inciting a riot and creates new crimes and enhanced penalties for aggravated rioting and aggravated inciting a riot. Increases penalties for assault or battery when committed in furtherance of a riot and requires a court to sentence a person convicted of battery of a law enforcement officer committed in furtherance of a riot to a six month minimum mandatory sentence. Creates the crime of mob intimidation, prohibiting a mob from forcefully compelling or attempting to compel another person to do any act or to assume or abandon a particular viewpoint. -

PENAL CODE (Act No.45 of 1907)

この刑法の翻訳は、平成十八年法律第三六号までの改正(平成18年5月28日施行) について、」 「法令用語日英標準対訳辞書 (平成18年3月版)に準拠して作成したもので す。 なお、この法令の翻訳は公定訳ではありません。法的効力を有するのは日本語の法令自 体であり、翻訳はあくまでその理解を助けるための参考資料です。この翻訳の利用に伴っ て発生した問題について、一切の責任を負いかねますので、法律上の問題に関しては、官 報に掲載された日本語の法令を参照してください。 This English translation of the Penal Code has been prepared (up to the revisions of Act No. 36 of 2006(Effective May 28, 2006)) in compliance with the Standard Bilingual Dictionary (March 2006 edition). This is an unofficial translation. Only the original Japanese texts of laws and regulations have legal effect, and the translations are to be used solely as reference material to aid in the understanding of Japanese laws and regulations. The Government of Japan shall not be responsible for the accuracy, reliability or currency of the legislative material provided in this Website, or for any consequence resulting from use of the information in this Website. For all purposes of interpreting and applying law to any legal issue or dispute, users should consult the original Japanese texts published in the Official Gazette. PENAL CODE (Act No.45 of 1907) PART I. GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter I. Scope of Application Article 1. (Crimes Committed within Japan) (1) This Code shall apply to anyone who commits a crime within the territory of Japan. (2) The same shall apply to anyone who commits a crime on board a Japanese vessel or aircraft outside the territory of Japan. Article 2. (Crimes Committed outside Japan) This Code shall apply to anyone who commits one of the following crimes outside the territory of Japan: (i)