Draft Voting Eligibility (Prisoners) Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

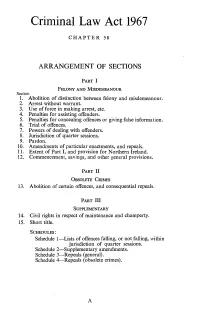

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

THE COMMON LAW in INDIA AUSTRALIA the Law Book Co

THE HAMLYN LECTURES TWELFTH SERIES THE COMMON LAW IN INDIA AUSTRALIA The Law Book Co. of Australasia Pty Ltd. Sydney : Melbourne : Brisbane CANADA AND U.S.A. The Carswell Company Ltd. Toronto INDIA N. M. Tripathi Private Ltd. Bombay NEW ZEALAND Sweet & Maxwell (N.Z.) Ltd. Wellington PAKISTAN Pakistan Law House Karachi The Common Law in India BY M. C. SETALVAD, Padma Vibhufhan, Attorney-General of India Published under the auspices of THE HAMLYN TRUST LONDON STEVENS & SONS LIMITED I960 First published in I960 by Stevens & Sons Limited of 11 New Fetter Lane in the City of London and printed in Great Britain by The Eastern Press Ltd. of London and Reading Stevens & Sons, Limited, London 1960 CONTENTS The Hamlyn Trust ----- page vii 1. RISE OF THE COMMON LAW 1 2. CIVIL LAW -------63 3. CRIMINAL LAW ------ us 4. THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION - - - - 168 EPILOGUE 224 HAMLYN LECTURERS 1949 The Right Hon. Lord Denning 1950 Richard O'Sullivan, Q.C. 1951 F. H. Lawson, D.C.L. 1952 A. L. Goodhart, K.B.E., Q.C, F.B.A. 1953 Sir Carleton Kemp Allen, Q.C, F.B.A. 1954 C. J. Hamson, M.A., LL.M. 1955 Glanville Williams, LL.D. 1956 The Hon. Sir Patrick Devlin 1957 The Right Hon. Lord MacDermott 1958 Sir David Hughes Parry, Q.C, M.A., LL.D., D.C.L. 1959 C. H. S. Fifoot, M.A., F.B.A. 1960 M. C. Setalvad, Padma Vibhufhan VI THE HAMLYN TRUST THE Hamlyn Trust came into existence under the will of the late Miss Emma Warburton Hamlyn, of Torquay, who died in 1941, aged eighty. -

Administration of Justice Act 1970

Status: Point in time view as at 03/04/2006. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Administration of Justice Act 1970. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Administration of Justice Act 1970 1970 CHAPTER 31 An Act to make further provision about the courts (including assizes), their business, jurisdiction and procedure; to enable a High Court judge to accept appointment as arbitrator or umpire under an arbitration agreement; to amend the law respecting the enforcement of debt and other liabilities; to amend section 106 of the Rent Act 1968; and for miscellaneous purposes connected with the administration of justice. [29th May 1970] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 By Criminal Justice Act 1991 (c. 53, SIF 39:1), s. 101(1), Sch. 12 para.23; S.I. 1991/2208, art. 2(1), Sch.1 it is provided (14.10.1991) that in relation to any time before the commencement of s. 70 of that 1991 Act (which came into force on 1.10.1992 by S.I. 1992/333, art. 2(2), Sch. 2) references in any enactment amended by that 1991 Act, to youth courts shall be construed as references to juvenile courts. Commencement Information I1 Act not in force at Royal Assent see s. 54(4); Act wholly in force 1.10.1971 PART I COURTS AND JUDGES High Court 1 Redistribution of business among divisions of the High Court. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART II OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES : Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH II 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are Abolition of abolished. -

Download (1MB)

Kennedy, Lewis (2020) Should there be a Separate Scottish Law of Treason? PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/81656/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] SHOULD THERE BE A SEPARATE SCOTTISH LAW OF TREASON? Lewis Kennedy, Advocate (MA, LLB, Dip LP, LLM) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow September 2020 Abstract: Shortly after the Union, the Treason Act 1708 revoked Scotland’s separate treason law in favour of England’s treason law. Historically, English treason law was imposed on Scots criminal law and was not always sensitive to the differences in Scottish legal institutions and culture. A review of the law of treason is in contemplation, it being under general attention more than at any time since the end of World War II. If there were to be a revival of UK treason law, the creation of a separate Scottish treason law may be a logical development given Scotland’s evolving devolution settlement. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Legislation and Regulations

STATUTES HISTORICALY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES SIGNIFICANT U.S. FEDERAL LEGISLATION AND REGULATIONS STATUTORY REFERENCES IN THE ENCYCLOPEDIA ENGLISH STATUTES A B C D E F G H I-K L M N O P R S T U-Z US STATUTES Public Acts and Codes Uniform Commercial Code Annotated (USCA) State Codes AUSTRALIAN STATUTES CANADIAN STATUTES & CODES NEW ZEALAND STATUTES FRENCH CODES & LEGISLATION French Civil Code Other French Codes French Laws & Decrees OTHER CODES 1 back to the top STATUTES HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES De Donis Conditionalibus 1285 ................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Quia Emptores 1290 ................................................................................................................................ 5 Statute of Uses 1536.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Statute of Frauds 1676 ............................................................................................................................................. 6 SIGNIFICANT SIGNIFICANT ENGLISH STATUTES Housing Acts ................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Land Compensation Acts ........................................................................................................................................ -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART IFELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1)All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2)Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12Arrest without warrant. (1)The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by [F3section 33 of the Magistrates’Courts Act 1980)]] and to attempts to committ any such offence; and in this Act, including any amendment made by this Act in any other enactment, ―arrestable offence‖ means any such offence or attempt. -

Criminal Forfeiture and the Sixth Amendment: the Role of the Jury at Common Law

FINNERAN.LUTHER.35.1 (Do Not Delete) 10/9/2013 6:17 PM CRIMINAL FORFEITURE AND THE SIXTH AMENDMENT: THE ROLE OF THE JURY AT COMMON LAW Richard E. Finneran & Steven K. Luther† Throughout its recent jurisprudence after Apprendi v. New Jersey, the Supreme Court has emphasized that its analysis of the Sixth Amendment jury trial right centers upon the historical role of the jury at common law. Just last year, in Southern Union Co. v. United States, the Court extended the Sixth Amendment jury trial right to criminal fines after concluding that the jury’s verdict determined the maximum fine that could be imposed at common law. The Court remained silent, however, with regard to another financial penalty commonly applied in the federal system: criminal forfeitures. Given that the Supreme Court has previously recognized that criminal forfeitures are “fines” within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment, it might be argued that the Sixth Amendment should likewise extend to criminal forfeitures under a formal application of Southern Union. Criminal forfeitures, however, draw from a distinct, complex, and largely unexplored historical tradition in which juries played little or no role. This Article, the first to provide a definitive account of that tradition, explains why the unique history of criminal forfeiture dictates that facts supporting forfeiture need not be found by a jury under the Sixth Amendment, insofar as those facts are not the sort traditionally given to juries at common law. † Richard E. Finneran is an Adjunct Professor of Law at Washington University School of Law, Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri (Asset Forfeiture Unit), and Special Attorney to the United States Attorney General under the supervision of the United States Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Missouri. -

A Parliament Act

International Law Research; Vol. 10, No. 1; 2021 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Modernising the Constitution - A Parliament Act Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 6, 2021 Accepted: February 3, 2021 Online Published: February 12, 2021 doi:10.5539/ilr.v10n1p101 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v10n1p101 A previous article has looked at modernising the law on the Crown, see Modernising the Constitution - A Crown Act.1 This article looks at the same in respect of Parliament. It may be noted, from the outset, that the legislation - and common law - on Parliament, is much simpler and less complicated than that on the Crown. Indeed, a large amount of this legislation is administrative (mundane) in nature. Also, much is non-contentious, having given rise to little caselaw. Further, there is a compelling case for consolidation since there are, presently, c. 68 Acts relating to Parliament, but they contain only c. 280 sections and much of the same is obsolete or couched in antiquated language which is scarcely intelligible. Thus, the essential issues are the following: Consolidation of Parliamentary Legislation; Modernising Crown Prerogatives relating to Parliament. In the latter case, most Crown prerogatives are now obsolete - as reflects the position after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. And, the few worth retaining should be placed in legislation - in order to give greater consistency and coherency to the same. -

Treason Act 1814

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Treason Act 1814. (See end of Document for details) Treason Act 1814 1814 CHAPTER 146 54 Geo 3 An Act to alter the Punishment in certain Cases of High Treason. [27th July 1814] Whereas in certain cases of high treason, as the law now stands, the sentence or judgement required by law to be pronounced or awarded against persons convicted or adjudged guilty of the said crime in such cases is that they should be drawn on a hurdle to the place of execution and there be hanged by the neck, but not until they are dead, but that they should be taken down again, and that when they are yet alive their bowels should be taken out and burnt before their faces, and that afterwards their heads should be severed from their bodies, and their bodies be divided into four quarters, and their heads and quarters to be at the King’s disposal:And whereas it is expedient in the said cases of high treason to alter the sentence or judgement now required by law: Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Short title given by Short Titles Act 1896 (c. 14) [1.] Form of sentence in case of high treason. In all cases of high treason in which as the law now stands the sentence or judgement ordained by law is as aforesaid, the sentence or judgement to be pronounced or awarded from and after the passing of this Act against any person convicted or adjudged guilty shall be, that [F1such person shall be liable to imprisonment for life] .