Pathways to Regional Sustainability: Best Practices for Wisconsin's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report

Girls Incorporated® of the Greater Capital Region 2012 Annual Report I 962 Albany St., Schenectady NY 12307 301 Washington Ave., Albany, NY 12206 518 / 374 – 9800 www.girlsinccapitalregion.org Inspiring ALL girls to be strong, smart, and bold!SM 2012 Annual Report Girls Inc. of the Greater Capital Region The Girls Inc. Mission Girls Incorporated® is committed to a vision of empowered girls and an equitable society. Through life-changing programs and experiences that help girls navigate gender, economic, and social barriers, Girls Inc. inspires all girls to be strong, smart, and bold.sm Research-based informal education programs encourage girls to take risks and master physical, intellectual, and emotional challenges. Curricula is delivered by trained, mentoring professionals and addresses the areas of culture and heritage, health and sexuality, leadership and community action, career and life planning, sports and adventure, and self-reliance and life skills. In a positive, all-girl environment, girls ages 5 to 18 are equipped to: achieve academically lead healthy and physically active lives manage money navigate media messages discover an interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) careers With our free after-school programs in both our Albany and Schenectady sites, the Summer Fun day camp program, all-day activities during school vacation weeks, community outreach programs, including Girls’ Summit and GE Technology Day and Job Shadow Day, and other programs including Eureka!®, our agency served a total of 11,407 girls in 2012. 2012 Annual Report Girls Inc. of the Greater Capital Region A Year of Transition In April, as the organization celebrated its milestone anniversary of serving girls in the Capital Region for 75 years, the Board of Directors was searching for a new Executive Director. -

2017-02 Intergovernmental Cooperation Agreement

ORDINANCE 2017-02 AN ORDINANCE OF THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS OF LOWER ALLEN TOWNSHIP, CUMBERLAND COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA, AMENDING THE CODE OF THE TOWNSHIP OF LOWER ALLEN, 1997 AT CHAPTER 23 INTERGOVERNMENTAL COOPERATION, BY CREATING A NEW ARTICLE XIII, AUTHORIZING THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS TO ENTER INTO A MUNICIPAL AGREEMENT WITH THE CAPITAL REGION COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS AND ITS MEMBER MUNICIPALITIES TO PARTICIPATE IN THE BUILDING CODE DEPARTMENT FOR BUILDING CODE INSPECTIONS AND PLAN REVIEWS. BE IT ENACTED AND ORDAINED by the Board of Commissioners of Lower Allen Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, (“Board”) and it is hereby enacted and ordained by the authority of the same as follows: SECTION 1: SHORT TITLE This Ordinance shall be known and may be cited as the Capital Region Council of Governments’ Building Code Department Ordinance. SECTION 2: LEGISLATIVE INTENT AND APPLICABILITY The background of this Ordinance and the legislative intention of the Board in enacting it are as follows: A. The Township of Lower Allen is a Municipality of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. B. The Capital Region Council of Governments is a consortium of Central Pennsylvania Municipalities. C. The Act of December 19, 1996, P.L. 1158, No. 177, referred to as the Intergovernmental Cooperation Law , 53 Pa. C.S. §2301, et seq. provides that two or more Municipalities may jointly cooperate in the exercise or in the performance of their respective governmental functions, powers or responsibilities. D. The Pennsylvania First Class Township Code authorizes Townships to enter into joint Municipal Agreements with other political subdivisions and member organizations, in making a joint purchase of services or to perform governmental powers and duties. -

Population, Health, and Environment Issues in the Philippines a Profile of the National Capital Region (NCR)

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU February 2008 POPULATION, HEALTH, AND ENVIRONMENT ISSUES IN THE PHILIPPINES A Profile of the National Capital Region (NCR) by Ma. Corazon G. De La Paz and Lisa Colson inking population, health, and environ- ment (PHE) issues is becoming increasingly important for the Philippines, where natural Lresources and public health and well-being are often negatively affected by factors such as popula- tion pressures and poverty. Understanding these Pangasinan connections—including the economic and social PACIFIC OCEAN Philippines Aurora context in which they occur—and addressing PHE Nueva Ecija issues in an integrated manner is critical for achiev- Tarlac ing sustainable development. Philippine Sea This regional PHE profile highlights key popu- Pampanga lation, health, and environment indicators and important development challenges for the National Bulacan Capital Region (NCR). The profile is designed Rizal Bataan to help educators, policymakers, and community National Capital Region leaders identify key threats to sustainable develop- Camarines ment and explore possible approaches to address- South Cavite Laguna ing them. This profile is part of a series covering China select regions of the Philippines, and is intended Sea Batangas as a companion publication to the Population Quezon Reference Bureau’s 2006 data sheet, Making the Link in the Philippines: Population, Health, and the rate of population growth in the Philippines (1.1 Environment.1 percent), the population will continue to grow in Overview of National Capital Region the coming years. The National Capital Region (NCR), also known NCR is the smallest of the country’s admin- as Metro Manila, covers the greater metropolitan istrative regions, yet it is the most populous and area of the city of Manila. -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

Staffing Contractors in the Capital Region

CONTRACTOR INFORMATION FOR CAPITAL REGION NY Physicians and Nurses Assignment America, LLC d/b/a Medical Staffing Network 6551 Park of Commerce Blvd. Boca Raton, FL 33487 Contact Name(s): Anita Vitallo 518-209-6905 [email protected] ExecuSearch Holdings, LLC d/b/a The Execu/Search Group 675 Third Avenue 5th Floor New York, New York 10017 Contact Name(s): Kyle Mattice 212-204-5102 [email protected] Fusco Personnel, Inc. 4 Executive Park Drive Albany, NY12203 Contact Name(s): Patricia A. Fusco 518-869-6100 Toll Free 800-343-8726 [email protected] General Healthcare Resources, LLC 1218 Central Ave. Suite 100 Albany, NY 12205 Contact Name(s): Amy Moulton Contract Administrator 610-684-4738 Toll Free 800-879-4471 [email protected] Maxim Healthcare Services, Inc. 7227 Lee Deforest Drive Columbia, MD 21046 Contact Name(s): Dawn Wilson 410-910-9224 [email protected] MSI Systems Corp. d/b/a Medical Search International 23 Vreeland Road Suite 210 Florham Park, NJ 07932 Contact Name(s): John Murray 862-251-0243 Toll Free 866-633-5665 [email protected] New Wave People, Inc. 490 Rt 33 West, Bldg 2, Unit 3 Millstone Township, NJ 08535 Contact Name(s): Raymond Paterek 732-786-9070 [email protected] Noor Associates, Inc. 295 Madison Ave, 15th Floor New York, NY 10017 Contact Name(s): Jacob Eletto 212-812-3389 [email protected] Penda Aiken, Inc. 330 Livingston Street Brooklyn, NY 11217 Contract Name(s): Gerry Evans Jeffrey Shlager 718-643-4880 Toll Free: 855-633-9291 [email protected] [email protected] Randstad North America, Inc. -

Women of Excellence Award Recipients

Albany-Colonie Regional Chamber Women of Excellence Award Recipients 2014 Distinguished Career Meng-Ling Hsiao, GE Power & Water Excellence in the Professions Curran Street, Pride Center of the Capital Region Excellence in Management 100+ Dr. Linda Richardson, Siena College Excellence in Management 1-99 Renee Abdou-Malta, ValueOptions Inc. Excellence in Sales & Marketing Carol Nieckarz, UBS Financial Services Excellence in Business Amy Johnson, Capstone Emerging Professional Ashley Jeffrey, Girls Inc. 2013 Distinguished Career Donna Lamkin, Chief Program Officer, Center for Disability Services Emerging Professional Kelly Brown Mateja, Director of Programs and Services, Colonie Senior Services Excellence in Business Faith A. Takes, President, Empire Education Corporation Excellence in Management 100+ Joan Hayner, CMPE, CEO, CapitalCare Medical Group Excellence in Management 1-99 Dr. Maryellen Gilroy, Vice President for Student Affairs, Siena College Excellence in Sales and Marketing Teresa Spadafora, Branch Manager, Vice President, First Niagara Bank Excellence in the Professions Sabrina Mosseau, BS, RN, OCN, Administrative Director/Medical Oncology, St. Peter's Health Partners 2012 Distinguished Career: Susan Scrimshaw, President, The Sage Colleges Excellence in Management (100+ employees): Joanne Kugler, Chief Information Officer, GE Energy Power and Water Business Excellence in Management (1-99 employees): Susan Commanda, C.U.C.E., Chief Executive Officer, Hudson River Community Credit Union Excellence in Business: Lauren Payne, Principal/co-owner, -

Capital Region Indicators Benchmarking Progress in New York’S Capital Region

Capital Region Indicators Benchmarking Progress in New York’s Capital Region Developing regional success through collaborative planning and partnerships Capital Region Indicators Benchmarking Progress in New York’s Capital Region Published by: Developing regional success through collaborative planning and partnerships One Park Place | Albany, New York 12205 | (518) 453-0850 | www.cdrpc.org August 2016 This Report was prepared with assistance from: Acknowledgements CDRPC is dedicated to connecting members of our community together through various means. As such, we are pleased to provide service-learning opportunities for students enrolled at area colleges and universities. We recognize that these opportunities provide meaningful real-world experiences to students so that they are ready to be productive employees once they graduate. CDRPC wishes to acknowledge Interim Dean R. Karl Rethemeyer, Assistant Professor Gang Chen, and PhD candidate Iseul Choi for their leadership and for the opportunity to work with the following Master of Public Administration candidates of Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy at the University at Albany. We thank them for their contributions to this Report: Sana Abdelkarim Abbi Griffin Elipha Pradhananga Tommy Alberico Kapil Gupta Conor Quinn Young Ran Bae Emily Hetzel Daesik Shin Kayla Bogdanowicz Matt Hinken Phillip Suruda Acknowledgements Yuanxing Chen Adelaide Hurlbert Jeffrey Vargas Robert Connors Aimee Johnson Philip Way Michael Coopersmith Anika Khan Corbin Woodruff Adele Costa Yoonhye Kim -

Cities of Tomorrow Challenges, Visions, Ways Forward

EN Cities of tomorrow Challenges, visions, ways forward October 2011 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. Copyrights: Cover: © ZAC DE BONNE - AKTIS ARCHITECTURE - Chapter 1: © iStockphoto Page 6: © EC - Page 9: © PHOTOGRAPHIEDEPOT Frank-Heinrich Müller - Chapter 2: © Tova Svanfeldt Page 15: © Corinne Hermant - Page 17: © iStockphoto - Page 20: © Krisztina Keresztely Page 23: © Carmen Vossen - Chapter 3: © Iván Tosics - Page 36: © iStockphoto - Page 37: © iStockphoto Page 41: © Henrik Johansson - Page 42: © La Citta Vita - Page 46: © EC - Page 47: © iStockphoto Page 53: © Anja Schlamann - Page 54: © Marie Schmerkova - Page 59: © iStockphoto - Chapter 4: © Iván Tosics Page 67: © Iván Tosics - Page 73: © iStockphoto - Page 77: © Bernard_in_va Page 82: © "Fragment de Tags" http://fragmentdetags.net/ - Page 83: © W. Vainqueur Conclusions: © City of Växjö © European Union, 2011 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-92-79-21307-6 doi:10.2776/41803 European Commission, Directorate General for Regional Policy Unit C.2 - Urban Development, Territorial Cohesion Wladyslaw Piskorz E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/conferences/citiesoftomorrow/index_en.cfm Unit B.1 – Communication, Information, Relations with Third Countries Raphaël Goulet Avenue de Tervuren 41 B - 1040 Brussels Fax: +32 22966003 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm The opinion expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. -

CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION from Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network

Report CAPITAL REGION RAIL VISION From Baltimore to Richmond, Creating a More Unified, Competitive, Modern Rail Network DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXISTING REGIONAL RAIL NETWORK 10 THE VISION 26 BIDIRECTIONAL RUN-THROUGH SERVICE 28 EXPANDED SERVICE 29 SEAMLESS RIDER EXPERIENCE 30 SUPERIOR OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION 30 CAPITAL INVESTMENT PROGRAM 31 VISION ANALYSIS 32 IMPLEMENTATION AND NEXT STEPS 47 KEY STAKEHOLDER IMPLEMENTATION ROLES 48 NEXT STEPS 51 APPENDICES 55 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decisions that we as a region make in the next five years will determine whether a more coordinated, integrated regional rail network continues as a viable possibility or remains a missed opportunity. The Capital Region’s economic and global Railway Express (VRE) and Amtrak—leaves us far from CAPITAL REGION RAIL NETWORK competitiveness hinges on the ability for residents of all incomes to have easy and Perryville Martinsburg reliable access to superb transit—a key factor Baltimore Frederick Penn Station in attracting and retaining talent pre- and Camden post-pandemic, as well as employers’ location Yards decisions. While expansive, the regional rail network represents an untapped resource. Washington The Capital Region Rail Vision charts a course Union Station to transform the regional rail network into a globally competitive asset that enables a more Broad Run / Airport inclusive and equitable region where all can be proud to live, work, grow a family and build a business. Spotsylvania to Richmond Main Street Station Relative to most domestic peer regions, our rail network is superior in terms of both distance covered and scope of service, with over 335 total miles of rail lines1 and more world-class service. -

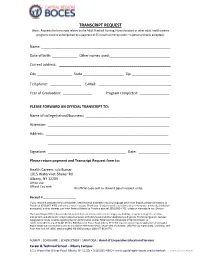

Transcript Request

TRANSCRIPT REQUEST (Note: Requests for transcripts related to the Adult Practical Nursing, Nurse Assistant or other adult health careers programs must be accompanied by a payment of $5 in cash or money order: no personal checks accepted.) Name: __________________________________________________________________ Date of birth: _____________ Other names used:_______________________________ Current address: _________________________________________________________ City __________________ State _____________________ Zip ____________________ Telephone: ________________ E-Mail: _____________________________________ Year of Graduation: _______________ Program completed: _______________ PLEASE FORWARD AN OFFICIAL TRANSCRIPT TO: Name of college/school/business: ___________________________________________ Attention: ______________________________________________________________ Address: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Signature: ________________________________________ Date: ________________ Please return payment and Transcript Request form to: Health Careers c/o Bursar 1015 Watervliet-Shaker Rd. Albany, NY 12205 Office Use Official Coy sent: Unofficial copy sent to student (upon request only): Receipt # ____________________ If you need the assistance of an interpreter, need material translated into any language other than English, please call Ottavio Lo Piccolo at (518) 862-4703 and leave a voice message. Thank you. Si usted necesita asistencia de un -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Ncr(National Capital Region)

NCR(NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION) The National Capital Region includes NCT-Delhi, nine districts of Haryana, six districts of Uttar Pradesh and one district of Rajasthan. Total area of the region is 34,144 sq. km. 1.National Capital Territory of Delhi (1,483 sq. km.) accounting for 4.4% of the total area of NCR. 2.Haryana Sub-Region with an area of 13,428 sq. km. accounting for 30.3% of the area of the State and 39.3% of the area of NCR comprising following nine districts: Faridabad, Gurgaon, Rohtak, Sonepat, Panipat, Jhajjar, Rewari, Mewat, Palwal 3. Rajasthan Sub-region comprises Alwar district which has an area of 8,380 sq. km. This account for 2.5% of the total area of the State and 24.5% of the area of NCR. 4.Uttar Pradesh Sub-region with an area of 10,853 sq. km. accounting for 4.5% of the area of the State and 31.8% of the area of NCR comprising following six districts: Meerut, Ghaziabad,Gautam Budh Nagar, Bulandshahr,Baghpat,Hapur ADMINISTRATION:- POLICY ZONES 1.NCT-Delhi • environmentally sustainable development and redevelopment taking into account the limitation of developable land and water. • No new major economic activities ,Only activities necessary to sustain the local population of NCT- Delhi 2.Central National Capital Region excluding NCT- Delhi • Contiguous towns of Ghaziabad-Loni, Noida, Gurgaon-Manesar, Faridabad-Ballabgarh, Bahadurgarh, Sonepat-Kundli and the extension of the Ridge in Haryana. • effectively reinforce/support NCT-Delhi by offering jobs, economic activities, comprehensive transport system, housing, social infrastructure and quality of environment, which are at par with the National Capital 3.