© Robert White Scott, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition 2010

American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition 2010 Louisville, Kentucky, USA 20-23 June 2010 Volume 1 of 21 ISBN: 978-1-61782-020-5 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2010) by the American Society for Engineering Education All rights reserved. Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2010) For permission requests, please contact American Society for Engineering Education at the address below. American Society for Engineering Education 1818 N Street, N.W., Suite 600 Washington, DC 20036-2479 Phone: (202) 331-3500 Fax: (202) 265-8504 www.asee.org Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2634 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 1 1118: SOFTWARE AND HARDWARE FOR EDUCATORS I 1166: TOWARD AN INTERACTIVE ENVIRONMENT FOR EMBEDDED SYSTEMS DESIGN ......................................................1 Fadi Obeidat, Ruba Alkhasawneh, Jerry Tucker, Robert Klenke 1304: AN APPLICATION-BASED APPROACH TO INTRODUCING MICROCONTROLLERS TO FIRST- YEAR ENGINEERING STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................................11 Warren Rosen, Eric Carr 45: HDL BASED DESIGN PROBLEMS FOR COMPUTER ARCHITECTURE ..................................................................................20 -

Anarcha-Feminism.Pdf

mL?1 P 000 a 9 Hc k~ Q 0 \u .s - (Dm act @ 0" r. rr] 0 r 1'3 0 :' c3 cr c+e*10 $ 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.... 1 Anarcha-Feminism: what it is and why it's important.... 4 Anarchism. Feminism. and the Affinity Group.... 10 Anarcha-Feminist Practices and Organizing .... 16 Global Women's Movements Through an anarchist Lens ..22 A Brief History of Anarchist Feminism.... 23 Voltairine de Cleyre - An Overview .... 26 Emma Goldman and the benefits of fulfillment.... 29 Anarcha-Feminist Resources.... 33 Conclusion .... 38 INTRODUCTION This zine was compiled at the completion of a quarters worth of course work by three students looking to further their understanding of anarchism, feminism, and social justice. It is meant to disseminate what we have deemed important information throughout our studies. This information may be used as a tool for all people, women in particular, who wish to dismantle the oppressions they face externally, and within their own lives. We are two men and one woman attempting to grasp at how we can deconstruct the patriarchal foundations upon which we perceive an unjust society has been built. We hope that at least some component of this work will be found useful to a variety of readers. This Zine is meant to be an introduction into anarcha-feminism, its origins, applications, and potentials. Buen provecho! We acknowledge that anarcha-feminism has historically been a western theory; thus, unfortunately, much of this ziners content reflects this limitation. However, we have included some information and analysis on worldwide anarcha-feminists as well as global women's struggles which don't necessarily identify as anarchist. -

Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2014 Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power Majken Jul Sorensen University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Sorensen, Majken Jul, Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2014. -

RNC New York Update #4 8-24-04

Starhawk: RNC New York Update #4 8-24-04 http://starhawk.org/activism/activism-writings/RNC_update4.html [Back to Starhawk's Activism Writings Page] [Back to Starhawk's Activism Page] RNC Update Number 4: Action Bardo by Starhawk I woke up this moring thinking about the Tibetan Book of the Dead, how it guides you through all the various hells that the spirit can travel through after death. It seemed we were trapped in some sort of action hell of plans that just wouldn’t come together and decisions that just couldn’t get made, and huge uncertainties. But perhaps that was just a reaction to an evening spent under the red gaze of the media. Monday night we did the anarchist panel. I spent the day putting together the press packets, lining up our press release and articles on “Are You an Anarchist? The Answer May Surprise You.” (You can see the whole thing on www.anarco-nyc.net) Brush and Yvonne made the press calls: we wanted to make the point that anarchists are not about chaos but about organizing, so we needed to be organized. We had eight speakers, and Eric Laursen as the moderator. Cindy Millstein began. She’s a very brilliant and serious theorist who once had the misfortune to be locked up with the Pagan Cluster in a mass arrest. She suffered through our 2 AM group trance and 5AM yoga session, the belly dance class, the radical cheerleading lesson, and the spiral dance, with good grace. Actually, to make this simple here is the speakers’ list from our press packet: 1. -

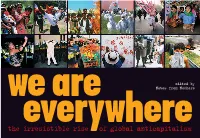

The Irresistible Rise of Global Anticapitalism for Struggling for a Better World All of Us Are Fenced In, Threatened with Death

edited by we are Notes from Nowhere everywhere the irresistible rise of global anticapitalism For struggling for a better world all of us are fenced in, threatened with death. The fence is reproduced globally. In every continent, every city, every countryside, every house. Power’s fence of war closes in on the rebels, for whom humanity is always grateful. But fences are broken. The rebels, whom history repeatedly has given the length of its long trajectory, struggle and the fence is broken. The rebels search each other out. They walk toward one another. They find each other and together break other fences. First published by Verso 2003 The texts in this book are copyleft (except where indicated). The © All text copyleft for non-profit purposes authors and publishers permit others to copy, distribute, display, quote, and create derivative works based upon them in print and electronic 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 format for any non-commercial, non-profit purposes, on the conditions that the original author is credited, We Are Everywhere is cited as a source Verso along with our website address, and the work is reproduced in the spirit of UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG the original. The editors would like to be informed of any copies produced. USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606 Reproduction of the texts for commercial purposes is prohibited www.versobooks.com without express permission from the Notes from Nowhere editorial collective and the publishers. All works produced for both commercial Verso is the imprint of New Left Books and non-commercial purposes must give similar rights and reproduce the copyleft clause within the publication. -

Entire Text of Climate Hope

CLIMATE HOPE CLIMATE HOPE On the FRONT LINES of the FIGHT AGAINST COAL TED NACE CLIMATE HOPE: On the Front Lines of the Fight Against Coal Ted Nace Copyright © 2010 by Ted Nace Published by CoalSwarm 1254 Utah Street, San Francisco, CA 94110 415-206-0906 [email protected] With the exception of the material listed below under “Adapted Material,” this book is covered by the Creative Commons Deed, a form of “copyleft” that encourages sharing under the following conditions: You are free • to Share—to copy, distribute and transmit the work • to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions • Attribution —You must attribute the work in the manner specifi ed by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). • Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar or a compatible license. With the understanding that • Waiver —Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. • Other Rights—In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: 1. Your fair dealing or fair use rights; 2. The author’s moral rights; 3. Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. • Notice —For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to the following web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ The full Creative -

Download: Transversal.At Umschlaggestaltung Und Basisdesign: Pascale Osterwalder

POSSEN DES PERFORMATIVEN GIN MÜLLER POSSEN DES PERFORMATIVEN Theater, Aktivismus und queere Politiken transversal texts transversal.at ISBN: 978-3-9501762-5-4 transversal texts transversal texts ist Textmaschine und abstrakte Maschine zugleich, Ter- ritorium und Strom der Veröffentlichung, Produktionsort und Plattform - die Mitte eines Werdens, das niemals zum Verlag werden will. transversal texts unterstützt ausdrücklich Copyleft-Praxen. Alle Inhalte, sowohl Originaltexte als auch Übersetzungen, unterliegen dem Copy- right ihrer AutorInnen und ÜbersetzerInnen, ihre Vervielfältigung und Reproduktion mit allen Mitteln steht aber jeder Art von nicht-kommer- zieller und nicht-institutioneller Verwendung und Verbreitung, ob privat oder öffentlich, offen. Dieses Buch ist gedruckt, als EPUB und als PDF erhältlich. Download: transversal.at Umschlaggestaltung und Basisdesign: Pascale Osterwalder transversal texts, 2015 eipcp Wien, Linz, Berlin, London, Zürich ZVR: 985567206 A-1060 Wien, Gumpendorferstraße 63b A-4040 Linz, Harruckerstraße 7 [email protected] eipcp.net ¦ transversal.at Das eipcp wird von der Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien gefördert. Inhalt Vorwort 09 Vorbemerkungen 13 I. Passagen des Theaters zur Performance 19 Die postheroische Instrumentalisierbarkeit des postdramatischen Theaters 31 Zum Begriff der Performativität 38 II. theatrum posse: Performative Handlungsmacht im theatrum gouvernemental 49 1. Theorie der Handlungsmacht: Spinoza, Deleuze und Hardt/Negri 49 Posse, Multitude und performative Bewegungen 56 2. theatrum gouvernemental 66 3. theatrum posse global 86 „Somos la dignidad rebelde“. Die zapatistische Maske 92 Ya Basta Association! Von den Tute Bianche zu den Disobbedienti 99 Block G8! Gouvernementale Szenarien und Possen in Heiligendamm 2007 108 Kampf gegen Grenzregime. Sans-Papiers, kein mensch ist illegal, no-border-Camps 118 „Reclaim the Space“. theatrum posse im Kampf um öffentliche Konflikträume 145 4. -

Glanville Ranulph

Welcome to C:ADM2010 We come together to take part in a conference where the main activity is to explore by listening, talking and questioning (conversing) rather than by listening to, and giving, prepared lectures: where the aim is to move forward, taking next steps as a result of these conversations, rather than reporting on the already discovered. In other words, this is a conference where the intention is to progress by conferring. That is the central feature of our conference: a conference of conversation, open minds and delight in the un-thought- of. And what better way to make an interesting conversation than to bring together people whose backgrounds and interests are different, yet who want to learn by listening to others, to find what can be shared? In other words, to transcend boundaries. So we are, by definition, practitioners and theorists from 4 different subjects, who explore across boundaries. But not just any 4 subjects. Subjects that already hold conversations together in pairs: art; cybernetics; design; mathematics. With all 4 together, we have a wider conversation, greater variety. Our 4 subjects have a special quality in common. Each is used to comment—throw light—on and inform other subjects. Perhaps mathematics is the most obvious case: a subject in its own right that is used everywhere to illuminate (and make operable) other subjects. But also a subject that can comment on itself: a subject which is a meta-subject, even to itself. Participants will undoubtedly hold individual positions in regard to these four subjects cybernetics, art, design and mathematics. -

17, September 12, 1982

Newsletter of the Arrerican Society for Cybemetics Barry Clemson, Editor 314 Shibles Hall Universi ty of Mai.."'le Orono, ME 04469 Nurober 17, Sept. 12, 1982 'Ihe address of the ASC is: 2131 G St. N.W., Washington, OC 20052 ASC Conferer1ce ASC Election Cybernetics and Education The Ballot for the ASC Election is 'Ihe (almest) final program for the enclosed and needs your i.mrediate Annual rreeting is attached. A attention (the ballots will be stellar array of scholars from c~m:ted Oct. 15 so that the new cybemetics and education have o:f7cers can meet with the current agreed to participate. We are otflcers during the October 18-21 expecting another excellent meeting in Colurnbus). Please rreeting. Send in your registra C?mplete and retum your ballot Wl thout delav. tion form for ~~e conference and J. the hotel as soon as possible. lJ::M Air Fares For East Coast Cyberneticians Wondering hcw to afford the II J.,:Jr----....__ qirfare to b~e ASC Conference ~1 ' ( ;· L1 Columbus??? You can go on People's Express Airlines for $88 round trip frorn rrost East Coast cities. People' s Express charges $44 for weekends (one way) and $69 for weekdays (one way). By Mika Peten tor l.ho Da.ylon DIIHy News Synposium: Autononw, from Physics to Political Science Translated for us by Jean A.H. Bourget It is, of course, too early to submit an assessment and a synthesis of the amazing symposium held at the 11 Centre Culturel Internationalu (International Cultural Centre) of Cerisy la Salle, from 11 to 17 June 1980, organized by J-P Dupuy et P. -

Two Sides of a Barricade

Two Sides of a Barricade Item Type Book Authors Scholl, Christian DOI 10.1353/book.23972 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 06/10/2021 23:35:44 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item https://www.sunypress.edu/p-5583-two-sides-of-a- barricade.aspx TWO SIDES OF A BARRICADE 33835_SP_SCH_FM_00i-xiv.indd 1 10/26/12 12:29 PM SUNY series, Praxis: Theory in Action —————— Nancy A. Naples, editor 33835_SP_SCH_FM_00i-xiv.indd 2 10/26/12 12:29 PM TWO SIDES OF A BARRICADE (Dis)order and Summit Protest in Europe Christian Scholl 33835_SP_SCH_FM_00i-xiv.indd 3 10/26/12 12:29 PM Cover images © Mat Jacob/Tendance Floue and Meyer/Tendance Floue Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2012 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production by Diane Ganeles Marketing by Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scholl, Christian, 1980– Two sides of a barricade : (dis)order and summit protest in Europe / Christian Scholl. p. cm. — (Praxis : theory in action) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

September 16 - 21 2002

September 16 - 21 2002 Two Weeks chock full of inspiring & ass kicking events created for your radical pleasure by a coalition of Ann Arbor Student, Community and Labor groups culminating in a mass mobiliza- tion at the Washington DC protests against the IMF and World Bank. Please see http://www.umich.edu/~aamgj/ for linked and updated info on the events. Monday, Sept. 16 7-10 pm @ Wedge Room in West Quad Hosted by Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee 12 - 2 pm @ The DIAG (ADC), Muslim Students Association (MSA), and Students Ann Arbor Mobilization for Global Justice (AAMGJ) Allied for Freedom and Equality (SAFE) Showing of “Another World is Possible” and “This is 7 pm - Viewing of BBC documentary on the massacre, What Democracy Looks Like”. Two films that help dispell “The Accused” the mass media myth about alternatives to corporate 8:15 pm - Speaker to lecture on Israeli war on Lebanon, globalization on what Seattle REALLY meant. and massacre. Humanitarian worker who was present at the time will give a short reflection of the site at ground 4-6 pm @ Michigan Union - Pond Room zero, and the utter destruction and devastation. Socially Konsious Info Theatre Troupe (SKITT ) - Guerilla 8:45 pm Viewing of award-winning Mai Masri film, & Forum Theatre “Frontiers of Dreams and Fears” Theatre of the Oppressed workshop: Learn theatre 9:45 pm - Reflection on tragedy, the status of techniques used at various demonstrations and practice Palestinian refugees today, and the bond that bridges up for the WB/IMF protests at the end of the month! all humanity together. -

CDP Guide to Worcester Fall 2007

CDP Guide to Worcester Fall 2007 Welcome to Clark and the CDP family! We hope that this guide can inform you about some local organizations and initiatives that may be of interest to you. They cover a wide range of community involvement and community issues and can be useful sources for employment, internships and general information. While this list is certainly not comprehensive, it’s a starting point. So get out there, be involved and walk the talk! -CDP 2 nd Years Resources at Clark Clark Sustainability Initiative The Clark Sustainability Initiative (CSI) is a nonhierarchical network that connects and augments the efforts of the administration, student, and faculty communities to further environmental sustainability at Clark University and in our larger society. http://www.clarku.edu/offices/environment/csi.cfm Dave Schmidt , Campus Sustainability Coordinator. (508) 793-7601 [email protected] Clark University Brothers and Sisters Program An undergraduate, student-run club which matches Clark students with local elementary-aged youth. Micki Davis, Director Community Engagement and Volunteering Center [email protected] (508) 421-3785 Community Engagement and Volunteering Center (CEV) On campus resource for students interested in local volunteer work. Help coordinate course-related service-learning projects. Located in the Corner House. Micki Davis, Director Community Engagement and Volunteering Center [email protected] (508) 421-3785 Jack Foley Jack Foley is the Vice President for Government and Community Affairs and Campus Services at Clark. He serves as the liaison between Clark and local, state and national government, making him an excellent resource for the local economic and social development work that Clark is doing in Main South.