Entire Text of Climate Hope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LUSEM Thesis Template

Brand Hostage How NGOs achieve their Strategic Goals on a Reputational Battlefield by Allan Su & Stefanie Wolff May 2017 Master’s Programme in International Marketing & Brand Management Supervisor: Mats Urde Examiner: Veronika Tarnovskaya Abstract Title: Brand Hostage - How NGOs achieve their Strategic Goals on a Reputational Battlefield Authors: Allan Su and Stefanie Wolff Course: BUSN39 Degree project in Global Marketing Date of Seminar: 2017-05-31 Supervisor: Mats Urde Purpose: The purpose of the study is to explore the phenomenon of brand hostage, with the aim to develop a framework and a definition for a deeper understanding of its modus operandi. Relevance: Over the past two decades, disruptive and successful NGO campaigns have increasingly targeted corporations, which makes the topic a major concern for managers. Nevertheless, both from an academic and practitioner's perspective the phenomenon remains elusive and neither well understood nor described in theory or practice. Methodology: A qualitative multiple-case study with a constructionist and interpretivist stance has been chosen to follow the inductive approach. For the data collection and analysis of that data, a grounded theory approach was applied. The selected NGO cases encompass three Greenpeace campaigns as well as one campaign each from the Organic Consumer Association against Starbucks and Green America against General Mills. Findings: The research findings indicate that the phenomenon of brand hostage is significantly more complex than stated in current literature, as demonstrated in the developed NGO brand hostage framework resulting from the case analyses. Furthermore, there exists the possibility of a continuing partnership after the resolution. Contributions: The research contributes to NGO, reputation management and crisis communication theory by providing a framework and definition of the brand hostage phenomenon. -

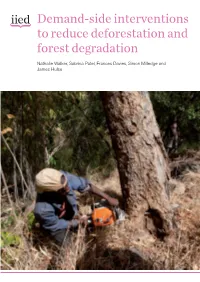

Demand-Side Interventions to Reduce Deforestation and Forest Degradation

Demand-side interventions to reduce deforestation and forest degradation Nathalie Walker, Sabrina Patel, Frances Davies, Simon Milledge and James Hulse DEMAnd-sidE inTERVENTIOns TO REDUCE DEFORESTATION And FOREST DEGRADATION Acknowledgements Increasing recognition of the role that commodity demand-side measures can play to address deforestation has resulted in a recent surge in efforts to assess progress and chart ways forward. As an initial step towards taking a holistic look at the range of available commodity demand-side measures, this paper was the result of a collaboration between the International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED), Global Canopy Programme (GCP), CDP Forests (formerly Forest Footprint Disclosure Project) and The Prince’s Rainforests Project (PRP). In this regard special thanks are due to Andrew Mitchell (GCP), James Hulse (CDP Forests), Frances Davis (GCP), Nathalie Walker (FFD), Edward Davey (PRP), Irene Klepinine (PRP), Georgia Edwards (PRP), Duncan Macqueen (IIED), Simon Milledge (IIED), Leianne Rolington (IIED) and Lucile Robinson (IIED). The paper builds on an international workshop held in February 2013, also co-convened by the International Institute of Environment and Development, Global Canopy Programme, CDP Forests and The Prince’s Rainforests Project. The active inputs from presenters and participants representing private sector, civil society and government are sincerely appreciated, and The Royal Society is acknowledged for providing an atmospheric venue setting within the City of London rooms. Barbara Bramble (National Wildlife Federation and also Chair of the Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels) deserves special mention for having chaired the event to ensure a day of informative and provocative discussions. Lastly, Duncan Brack and Alison Hoare (Chatham House) are acknowledged for their efforts to enable coordinated preparations and follow-up to this work. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Fossil Fuel Racism How Phasing out Oil, Gas, and Coal Can Protect Communities

© Les Stone / Greenpeace Fossil Fuel Racism How Phasing Out Oil, Gas, and Coal Can Protect Communities PUBLISHED: APRIL 13, 2021 www.greenpeace.org/usa/fossil-fuel-racism Contents Executive Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 1 . Environmental Justice . 7 2 . Fossil Fuels and Air Pollutants . 10 AUTHORS 3 . Fossil Fuel Phaseout . 12 Tim Donaghy, Ph.D. 4 . Extraction . 15 Charlie Jiang Oil and Gas Extraction . 15 Coal Mining . 18 CONTRIBUTORS Colette Pichon Battle, Esq. 5 . Processing & Transport . 19 Emma Collin Oil Refining, Natural Gas Processing & Petrochemical Manufacturing . 19 Janet Redman Pipelines & Terminals . 23 Ryan Schleeter 6 . Combustion . 24 General Exposure to Criteria Air Pollution . 24 SPECIAL THANKS TO Coal and Natural Gas Power Plants . 25 Noel Healy Aidan Farrow Mobile Sources and Traffic Exposure . 26 Anusha Narayanan 7 . Climate Impacts . 28 Ashley Thomson 8 . Policy Recommendations . 30 Caroline Henderson Charlie Cray 1. End fossil fuel racism and reverse the legacies of historical injustices . 30 Jonathan Butler 2. Phase out fossil fuel production . 31 Angela Mooney D’Arcy 3. Ensure no worker or community is left behind . 31 Michael Ash 4. Enact a green and just economic recovery . 31 EDITOR 5. Protect and expand our democracy to make it work for all people . 32 Charlie Jiang Acknowledgments . 33 Endnotes . 34 DESIGNED BY Kyle McKibbin Cover image by Les Stone © Robert Visser / Greenpeace This report is endorsed by: Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments ...and more. See the full list at: http://greenpeace.org/usa/fossil-fuel-racism FOSSIL FUEL RACISM | II Executive Summary Fossil fuels — coal, oil, and gas — lie at the heart of the crises we face, including public health, racial injustice, and climate change. -

Center for International Environmental Law Citizens Network For

Center for International Environmental Law ● Citizens Network for Sustainable Development ● Global Forum on Oceans, Coasts, and Islands ● Greenpeace – USA ● National Wildlife Federation ● Natural Resources Defense Council ● Pathfinder International ● Sierra Club ● SustainUS -United States Youth for Sustainable Development ● Union of Concerned Scientists ● Women’s Environment and Development Organization ● World Information Transfer ● Worldwatch Institute September 29, 2009 President Barack Obama The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20500 Dear President Obama: We are writing, on behalf of civil society organizations representing more than a million Americans, to request that the U.S. Government enthusiastically support the proposal now before the United Nations to hold an Earth Summit in Brazil in 2012. We hope that you will see the Summit as an opportunity to consolidate the gains made in your first Administration towards sustainable development and to catalyze actions worldwide to build a new green global prosperity. We do not have a moment to lose. During your July 2008 visit to Berlin, you articulated the urgency of our global challenges. We could not agree more that “this is the moment when we must come together to save this planet. Let us resolve that we will not leave our children a world where the oceans rise and famine spreads and terrible storms devastate our lands.” The Government of Brazil is proposing bringing all of the world’s Presidents and Prime Ministers together on the 20th anniversary of the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro. This Rio Earth Summit was historic in establishing international norms and institutions around the concept of “sustainability.” The Summit resulted in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change which is the basis for the further development of the international climate regime in Copenhagen this December. -

![[Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] Vision Fr Movemen N T](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9364/daniel-14-santiago-chile-vision-fr-movemen-n-t-669364.webp)

[Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] Vision Fr Movemen N T

2002 [Daniel, 14, Santiago, Chile] vision fr movemen n t oceans ancient forests climate toxics nuclear power and disarmament genetic engineering [featuring year 2001 financial statements] 2001financial year [featuring [Bill Nandris, one of the‘Star Wars 17’] 1 greenpeace 2002 brunt of environmental degradation of environmental brunt It is the poor that normally bear the It is the poor that normally “ shatter spirit In Brazil, with great The situation is serious, but Summit’s innovative economics and the actions fanfare, governments set not hopeless. On the plus Agenda 21 – millions of of states are pulling in a out on the ‘road to side, the past decade has people around the world quite different direction. sustainability’. But most of seen the adoption of are tackling local Individuals, businesses and them have now ground to a significant environmental environmental issues with countries have a choice. halt, mired in inaction and legislation at national and dedication, energy and no We can have limitless cars As I write this, final preparations are underway for the Earth Summit in Johannesburg. in Summit Earth the for underway are this, preparations write final I As a return to ‘business as international levels and an small measure of expertise. and computers, plastics usual’.The road from Rio is increasing ecological In schools, children from and air-freighted knee-deep in shattered awareness among policy virtually every country are vegetables, but in exchange promises, not least the makers and scientists. learning about the we get Bhopal and craven caving-in by the But perhaps most environment and its Chernobyl, species USA to the interests of the significant of all is the importance for their future. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

Anarcha-Feminism.Pdf

mL?1 P 000 a 9 Hc k~ Q 0 \u .s - (Dm act @ 0" r. rr] 0 r 1'3 0 :' c3 cr c+e*10 $ 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.... 1 Anarcha-Feminism: what it is and why it's important.... 4 Anarchism. Feminism. and the Affinity Group.... 10 Anarcha-Feminist Practices and Organizing .... 16 Global Women's Movements Through an anarchist Lens ..22 A Brief History of Anarchist Feminism.... 23 Voltairine de Cleyre - An Overview .... 26 Emma Goldman and the benefits of fulfillment.... 29 Anarcha-Feminist Resources.... 33 Conclusion .... 38 INTRODUCTION This zine was compiled at the completion of a quarters worth of course work by three students looking to further their understanding of anarchism, feminism, and social justice. It is meant to disseminate what we have deemed important information throughout our studies. This information may be used as a tool for all people, women in particular, who wish to dismantle the oppressions they face externally, and within their own lives. We are two men and one woman attempting to grasp at how we can deconstruct the patriarchal foundations upon which we perceive an unjust society has been built. We hope that at least some component of this work will be found useful to a variety of readers. This Zine is meant to be an introduction into anarcha-feminism, its origins, applications, and potentials. Buen provecho! We acknowledge that anarcha-feminism has historically been a western theory; thus, unfortunately, much of this ziners content reflects this limitation. However, we have included some information and analysis on worldwide anarcha-feminists as well as global women's struggles which don't necessarily identify as anarchist. -

Winds of Change the Newsletter of The

Winds of Change the newsletter of the March 2009 Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition E Huntington, WV www.ohvec.org Residents Vent Concerns to DEP by Joanie Newman, excerpted from Jan. 16, 2009, Coal Valley News Seventy-nine-year old Donald Maxey travelled the 6-hour drive from his home in Mt. Airy, Maryland, to Ashford Rumble Elementary School last week to voice his complaints with the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). “I didn’t want to miss this because I was born and raised at Nellis and have family all the way up to Ridgeview,” he said. Maxey said he recalls walking over Bull Creek Mountain. “You couldn’t do that continued on page 4 MTR a threat to Hawks Nest State Park environs. See pages 3 and 16. Bush Midnight Rule Change Exposed to Sunlight of Justice In January, OVEC joined with other groups in suing planted by the Bush administration that an EPA headed by over one of Bush’s final controversial acts. With our legal Lisa Jackson stands to inherit,” Earthjustice attorney Jennifer challenge, we seek to overturn Bush’s last-minute repeal of Chavez said. “With this lawsuit, we are doing what we can the stream buffer zone rule – an environmental law that, to make it easier for the incoming administration to undo the since 1983, has prohibited surface coal mining activities damage wrought by the last one and restore our nation’s within 100 feet of flowing streams. commitment to protecting the waters and summits of the As you may have noticed, the former stream buffer Appalachians.” zone rule was ignored by coal companies and not enforced As this lawsuit proceeds, we are hoping for better by so-called regulatory agencies, but before Bush axed the coal-related enforcement under the Obama administration. -

Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2014 Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power Majken Jul Sorensen University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Sorensen, Majken Jul, Humorous Political Stunts: Nonviolent Public Challenges to Power, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2014. -

Winds of Change the Newsletter of The

Winds of Change the newsletter of the June 2010 Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition E Huntington, WV www.ohvec.org Victory! Passing Stronger Cemetery Legislation by Robin Blakeman operations and other land-altering After at least three years of activities. trying to more effectively protect During our first three years cemeteries, we finally did it! This year, of work, four separate bills were at OVEC’s urging, citizens and introduced; none resulted in new members of the faith community joined legislation, but all increased elected forces in lobbying for the passage of officials’ awareness of the need to HB 4457, which improves cemetery protect cemeteries. protection throughout West Virginia. We built allies within faith Our efforts to protect community groups and other cemeteries were sparked by an organizations, such as genealogical increasing number of reports of societies and the WV Perpetual cemetery desecration and blocked Care Cemetery Board. Prominent access to family cemeteries. representatives from Catholic, Many of the access and Episcopalian, Methodist, Unitarian desecration complaints are related to and Presbyterian faith groups lent mountaintop removal operations, but support. For the past two years, there are statewide problems with the WV Council of Churches has protecting cemeteries from natural gas endorsed the need for improved cemetery protection Anderson “Devil Anse” legislation in its legislative Supreme Court Pilot Project Approved Hatfield’s grave is just one policy guide. of hundreds in WV by Carol Warren During the 2009 overshadowed by MTR Coalition partners of WV Citizens for Clean WV legislative interims, a Elections were very encouraged when Governor Manchin mining operations (center announced in his State of the State address that he planned background). -

Uncommon Productions Presents

Uncommon Productions and DADA Films Present A Film by Bill Haney World Premiere 2011 Sundance Film Festival Opens in Theaters June 2011 Publicity: Distribution and Marketing: Los Angeles Dada Films Fredell Pogodin & Associates MJ Peckos Fredell Pogodin /Bradley Jones (310)273-1444 (323)931-7300 [email protected] [email protected] New York required viewing FALCO INK Steven Raphael Shannon Treusch/Janice Roland/Erin Bruce (212)206-0118 (212)445-7100 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Washington, DC Jamie Shor PR Collaborative (202) 339-9598 [email protected] 95 minutes • Rated PG SYNOPSIS In the valleys of Appalachia, a battle is being fought over a mountain. It is a battle with severe consequences that affect every American, regardless of their social status, economic background or where they live. It is a battle that has taken many lives and continues to do so the longer it is waged. It is a battle over protecting our health and environment from the destructive power of Big Coal. The mining and burning of coal is at the epicenter of America’s struggle to balance its energy needs with environmental concerns. Nowhere is that concern greater than in Coal River Valley, West Virginia, where a small but passionate group of ordinary citizens are trying to stop Big Coal corporations, like Massey Energy, from continuing the devastating practice of Mountain Top Removal. David, himself, never faced a Goliath like Big Coal. The citizens argue the practice of dynamiting the mountain’s top off to mine the coal within pollutes the air and water, is responsible for the deaths of their neighbors and spreads pollution to other states.