Cc-5:History of India(Ce 750-1206)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

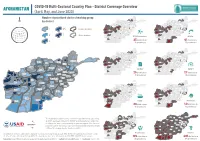

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Kingdoms Ii. It Is Believed That the Rajputs Were About 36 Hindu

Grade: VII Subject: Social Science Chapter No.: 2 Chapter Name: New Kings and Kingdoms Learning Resource Solutions Milestone 1 Answer the following questions by choosing the correct option from those given below it. 1. (iii) Palas 2. (i) Chalukyas 3. (iii) Parameshvaravarman Match the words in Column A with those given in Column B. 4. (a)-(ii), (b)-(iii), (c)-(i) Answer the following questions in not more than 30 words each. 5. Hinduism was patronised by the Palas as they had built many temples and monasteries. 6. The Gurjara-Pratihara, also known as the Imperial Pratihara, was an imperial dynasty that came to India in about the 6th century and established independent states in Northern India, from the mid-7th to the 11th century. 7. The Rajput clans that belonged to the fire family were called Agnikulas. The four important Agnikulas dynasties were Chauhans (or Chamanas), Gurjara Pratiharas (or Pratiharas), Paramaras (or Pawars) and Chalukyas (or Solankis). Answer the following questions in not more than 80 words each. 8. i. The Rajputs were the most important rulers of north-west India. The fall of the kingdom of Harshavardhana was accompanied with the rise of the Rajput clan in the 7th and 8th century. ii. It is believed that the Rajputs were about 36 Hindu dynasties. They belonged to sun family (called Suryavanshi) or moon family (called Chandravanshi). Some examples are the Chandelas in Bundelkhand, the Guhilas in Mewar, and the Tomaras in Haryana and Delhi. iii. Four Rajput clans that belonged to the fire family (called Agnikulas) became more important. -

Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II

VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE Medieval India TNPSC GROUP – I & II An ISO 9001 : 2015 Institution | Providing Excellence Since 2011 Head Office Old No.52, New No.1, 9th Street, F Block, 1st Avenue Main Road, (Near Istha siddhi Vinayakar Temple), Anna Nagar East – 600102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 Branches SALEM KOVAI No.189/1, Meyanoor Road, Near ARRS Multiplex, No.347, D.S.Complex (3rd floor), (Near Salem New bus Stand), Nehru Street,Near Gandhipuram Opp. Venkateshwara Complex, Salem - 636004. Central Bus Stand, Ramnagar, Kovai - 9 Ph: 0427-2330307 | 95001 22022 Ph: 75021 65390 Educarreerr Location VIVEKANANDHA EDUCATIONA PATRICIAN COLLEGE OF ARTS SREE SARASWATHI INSTITUTIONS FOR WOMEN AND SCIENCE THYAGARAJA COLLEGE Elayampalayam, Tiruchengode - TK 3, Canal Bank Rd, Gandhi Nagar, Palani Road, Thippampatti, Namakkal District - 637 205. Opp. to Kotturpuram Railway Station, Pollachi - 642 107 Ph: 04288 - 234670 Adyar, Chennai - 600020. Ph: 73737 66550 | 94432 66008 91 94437 34670 Ph: 044 - 24401362 | 044 - 24426913 90951 66009 www.vetriias.com © VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE First Edition – 2015 Second Edition – 2019 Pages : 114 Size : (240 × 180) cm Price : 220/- Published by: VETRII IAS STUDY CIRCLE F Block New No. 1, 9th Street, 1st Avenue main Road, Chinthamani, Anna Nagar (E), Chennai – 102. Phone: 044-2626 5326 | 98844 72636 | 98844 21666 | 98844 32666 www.vetriias.com E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] Feedback: [email protected] © All rights reserved with the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher, will be responsible for the loss and may be punished for compensation under copyright act. -

Migration History of the Afro-Eurasian Transition Zone, C. 300

Chapter 1 Migration History of the Afro-Eurasian Transition Zone, c. 300–1500: An Introduction (with a Chronological Table of Selected Events of Political and Migration History) Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, Lucian Reinfandt and Yannis Stouraitis When the process of compilation of this volume started in 2014, migration was without doubt already a “hot” topic. Yet, it were only the events of 2015,1 which put migration on top of the discussion about the Euro and the economic crisis in the agenda of politicians, the wider public and the media. In this heated debate, the events of past migrations have been employed in a biased manner as arguments against a new “Völkerwanderung” destined to disintegrate Eu- rope as it did with the (Western) Roman Empire. Thus, the present volume could be seen, among other things, also as an effort to provide a corrective to such oversimplifying recourses to the ancient and medieval period.2 It should be noted, however, that it was planned and drafted before the events. The volume emerged from a series of papers given at the European Social Science History Conference in Vienna in April 2014 in two sessions on “Early Medieval Migrations” organized by Professors Dirk Hoerder and Johannes Koder. Their aim was to integrate the migration history of the medieval period into the wider discourse of migration studies and to include recent research. The three editors have added contributions by specialists for other periods and regions in order to cover as wide an area and a spectrum of forms of migration as possible. Still, it was not possible to cover all regions, periods and migra- tion movements with the same weight; as one of the anonymous reviewers properly pointed out, the “work’s centre of gravity is (…) between the Eastern Mediterranean region and the Tigris/Euphrates”, with Africa not included in a similar way as Asia or Europe. -

Iran's Long History and Short-Term Society

IJEP International Journal of Economics and Politics Iran’s Long History and Short-Term Society 1 Homa Katouzian Oxford University,UK* ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Iran has a long history and a short-term society. It is a country with thousands Date of submission: 27-04-2019 of years of history, the great variety of every aspect of which is at least partly Date of acceptance: 21-07-2019 responsible for the diversity of opinions and emotions among its peoples. It is an ancient land of the utmost variety in nature, art and architecture, languages, literature and culture. When the Greeks (from whom European civilisations JEL Classification: B10 descend) came across the Iranians first, Persian Iranians were ruling that country as the Persian empire, and they called it ‘Persis’. Just as when the A14 N10 Persians first came into contact with Ionian Greeks, they called the entire Greek lands ‘Ionia’. To this day Iranians refer to Greece as Ionia (=Yunan) and the Greeks as Ionians (=Yunaniyan). Thus from the ancient Greeks to 1935, Keywords: Iran was known to Europeans as Persia; then the Iranian government, prompted Iran’s Long History by their crypto-Nazi contacts in Germany, demanded that other countries Term Society officially call it Iran, largely to publicise the Aryan origins of the country. This Iran meant that, for a long time, almost the entire historical and cultural connotations of the country were lost to the West, the country often being confused with Iraq, and many if not most mistakenly thinking that it too was an Arab country. -

Mahmud Ghazni, the Pillager of Enormous Wealth from India

International Journal of Scientific Research and Engineering Development-– Volume 3 Issues 1 Jan- Feb 2020 Available at www.ijsred.com RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Mahmud Ghazni, The Pillager of Enormous Wealth From India Adil Firdous Wani B.A, M.A History, M.A Political Science, Department of History. Pursuing PhD from Himalayan University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. Abstract: Mahmud Ghazni (998-1030 A.D) also known as Mahmud Zabuli was one of the greatest rulers of the eleventh Century. He became the first independent ruler of the Ghaznavid Dynasty. After coming into power, he carried as many as 17 raids in India. He defeated many Rajas in the eleventh century. His am was not to rule over other territories by dilating his empire but he was interested in pillaging everything from the people of India. He was a brave and courageous man who tried to establish Muslim rule in India but he failed somehow to establish the Muslim rule in India. It is said that Mahmud Zabuli had destroyed many temples in India and had assumed different titles at different times. This article helps us to reconstruct the early history of Mahmud Ghazni and it also provides us the information about his early carrier, expeditions and accession of Mahmud Ghazni. Keywords:- Mahmud Zabuli (998-1030 A.D), 17 raids, Ghazni, Turks, Muslim rule in India, Amin-ul-Milat, Yamin-ud-Daula, Expeditions. I. Early Carrier of Mahmud Ghazni: In the beginning Mahmud Ghazni vanquished the samanids and expand his territory up to oxus. He conquered Kohistan in 1001 C.E. Thereafter, Mahmud Zabuli faced Jaipal, a ruler of Hindushahi Dynasty. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Local Perspectives on Peace and Elections Ghazni Province, South-Eastern Afghanistan

Local perspectives on peace and elections Ghazni Province, south-eastern Afghanistan Interviews conducted by Abdul Hadi Sadat, a researcher with Unit (AREU), the Center for Policy and Human Development over 15 years of experience in qualitative social research with (CPHD) and Creative Associates International. He has a degree organisations including the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation injournalism from Kabul University. ABSTRACT The following statements are taken from longer their views on elections, peace and reconciliation. interviews with community members across two Respondents’ ages and ethnic groups vary, as do their different rural districts in Ghazni Province in south- levels of literacy. Data were collected by Abdul Hadi eastern Afghanistan between November 2017 and Sadat as part of a larger research project funded by the March 2018. Interviewees were asked questions about UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Female NGO employee I think the international organisations’ involvement is very Government officials and the IEC [Independent Election vital and they have an important role in elections, but I Commission] are not capable of talking with the Taliban don’t think they will have an important role in reconciliation regarding the election, but community representatives can with the Taliban because they themselves do not want convince them not to do anything to disrupt the election and Afghanistan to be in peace. If they wanted this we would even encourage them to participate in the election process. have better life. They have the power to force the Taliban to reconcile with Afghanistan government. Female youth, unemployed I don’t know for sure whether the Taliban will allow elections Male village elder to take place here or not, but in those villages where the For decades we have been experiencing war so all people security is low the Taliban will not let the people go to the are very tired with fighting, killing and bombing. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Orthographic Transparency and the Ottoman Abjad Maithili Jais

Orthographic Transparency and the Ottoman Abjad Maithili Jais University of Florida Spring 2018 I. Introduction In 2014, the debate over whether Ottoman Turkish was to be taught in schools or not was once again brought to the forefront of Turkish society and the Turkish conscience, as Erdogan began to push for Ottoman Turkish to be taught in all high schools across the country (Yeginsu, 2014). This became an obsession of a news topic for media in the West as well as in Turkey. Turkey’s tumultuous history with politics inevitably led this proposal of teaching Ottoman Turkish in all high schools to become a hotbed of controversy and debate. For all those who are perfectly contented to let bygones be bygones, there are many who assert that the Ottoman Turkish alphabet is still relevant and important. In fact, though this may be a personal anecdote, there are still certainly people who believe that the Ottoman script is, or was, superior to the Latin alphabet with which modern Turkish is written. This thesis does not aim to undertake a task so grand as sussing out which of the two was more appropriate for Turkish. No, such a task would be a behemoth for this paper. Instead, it aims to answer the question, “How?” Rather, “How was the Arabic script moulded to fit Turkish and to what consequence?” Often the claim that one script it superior to another suggests inherent judgement of value, but of the few claims seen circulating Facebook on the efficacy of the Ottoman script, it seems some believe that it represented Turkish more accurately and efficiently. -

Muslim Invasions on India in the Medieval Period and Its Impact

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH ISSN NO : 2236-6124 Muslim Invasions on India in the Medieval Period and Its Impact S.M. Gulam Hussain, Lecturer in History Department of History, Osmania College (A), Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh ABSTRACT: Medieval period is an important period in the history of India because of the developments in the field of art and languages, culture and religion. In the early medieval age India was on the threshold of phenomenal changes in the domains of polity, economy, society and culture. The impact of these changes is visible even today influencing the growth of India as one nation. Early Medieval period witnessed wars among regional kingdoms from north and south India where as late medieval period saw the number of Muslim invasions by Mughals, Afghans and Turks. The impact of Islam on Indian culture has been inestimable. It permanently influenced the development of all areas of human endeavour- language, dress, cuisine, all the art forms, architecture and urban design, and social customs and values. This paper describes the Muslim invasions on India in the Medieval Period and its impact. Keywords: Medieval period, Culture, Religion, Muslim invasions, Inestimable 1. INTRODUCTION: Medieval period lasted from the 8th to the 18th century CE with early Medieval period from the 8th to the 13th century and the late medieval period from the 13th to the 18th century. Early Medieval period witnessed wars among regional kingdoms from north and south India where as late medieval period saw the number of Muslim invasions by Mughals, Afghans and Turks. In the early medieval age India was on the threshold of phenomenal changes in the domains of polity, economy, society and culture.