Interviewing the Embodiment of Political Evil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engaging with Videogames

INTER - DISCIPLINARY PRESS Engaging with Videogames Critical Issues Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Lisa Howard Dr Ken Monteith Advisory Board Karl Spracklen Simon Bacon Katarzyna Bronk Stephen Morris Jo Chipperfield John Parry Ann-Marie Cook Ana Borlescu Peter Mario Kreuter Peter Twohig S Ram Vemuri Kenneth Wilson John Hochheimer A Critical Issues research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/critical-issues/ The Cyber Hub ‘Videogame Cultures and the Future of Interactive Entertainment’ 2014 Engaging with Videogames: Play, Theory and Practice Edited by Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2014 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-295-9 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2014. First Edition. Table of Contents Introduction ix Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans Part 1 Gaming Practices and Education Toward a Social-Constructivist View of Serious Games: Practical Implications for the Design of a Sexual Health Education Video Game 3 Sara Mathieu-C. -

Kalle Kotipsykiatri -Tietokone- Ohjelma Tekoälyn Popularisoijana 1980-Luvulla

THS Tekniikan Waiheita ISSN 2490-0443 Tekniikan Historian Seura ry. 37. vuosikerta:3 2019 https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen Jaakko Suominen https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1352-7699 To cite this article: Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen, ”'Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa': Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokoneohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-lu- vulla” Tekniikan Waiheita 37, no. 3 (2019): 6–30. https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 To link to this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski1, Markku Reunanen2 & Jaakko Suominen3 Tekoälyä koskevalla vilkkaalla julkisuuskeskustelulla on oma monipuolinen taustahistoriansa. Artikke- lissa käsitellään Pekka Tolosen luoman Kalle kotipsykiatri -ohjelman vaiheita 1980-luvun tietokoneleh- distössä. Kalle kotipsykiatri tunnetaan varhaisena esimerkkinä tekoälyä simuloivasta keskusteluohjel- masta, jonka Commodore 64 -käännösversion koodivirheitä korjailtiin yli vuoden ajan kotitietokoneisiin erikoistuneessa MikroBitti -lehdessä. Johdanto Tekoälyltä koskevalta keskustelulta voi tuskin välttyä nykyään missään. Tekoäly esiintyy uu- tisissa, poliittisissa puheissa, mediajulkisuudessa sekä ihmisten kasvokkais- ja nettikeskuste- luissa. Tekoälyllä viitataan muun muassa robotteihin, erilaisiin digitaalisiin -

Commodore 64

Commodore 64 Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments $100,000 Pyramid, The Box Office 10th Frame: Pro Bowling Simulator Access Software 1942 Capcom 1943: The Battle of Midway Capcom 2 for 1: Combat Lynx / White Viper Gameware (Tri-Micro) 2 on One: Bump, Set, Spike / Olympic Skier Mastertronic 2 on One: L.A. SWAT / Panther Mastertronic 221B Baker St. Datasoft 3 Hit Games: Brian Bloodaxe / Revelation / Quovadis Mindscape 3D-64 Man Softsmith Software 4th & Inches Accolade 4x4 Off-Road Racing Epyx 50 Mission Crush Strategic Simulations Inc (... 720° Mindscape A Bee C's Commodore A.L.C.O.N. Taito ABC Caterpillar Avalon Hill Game Company ABC Monday Night Football Data East Ace of Aces: Box Accolade Ace of Aces: Gatefold Accolade ACE: Air Combat Emulator Spinnaker Software AcroJet: The Advanced Flight Simulator MicroProse Software Action Fighter Mindscape / Sega Adult Poker Keypunch Software Advance to Boardwalk GameTek Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Champions of Krynn Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Curse of the Azure Bonds Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Death Knights of Krynn Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Dragons of Flame Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Gateway to the Savage Frontier Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes of the Lance Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Hillsfar Strategic Simulations Inc (... Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Pool of -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Amendments of the Senate to the Bill (H

1955 CONGRESSIONAL 'RECORD - HOUSE 7889 Powell, Royce M., Jr., 01882612. Griffen, Charles F. Murphy, Walter H. thority of the Administrator of Veterans' Shareck, Everett P., 01924705. Gudger, Robert M, Murray, Roland N., Jr;· Affairs to make direct loans, and to author Sullivan, John P., Jr., 01876446. Hall, Harry T. Parson, Joe W. ize the Administrator- to make additional Tinker, Martin, Jr., 01881,624. Hamel, John F., Jr. Pfeil, Kenneth A. types of direct loans thereunder, and for Traylor, Robert J., 01886559. · Hammond, Rudolph Pillitteri, Salvatore J. other purposes. Waldron, Garald L., 02030466. E., 04041563. Polak, Alexander P. Weston, Robert A., 0973~59. Hannum, Alden 0.- Powers, Donald L. The m~ssage also announced that the Haught, V. Ronnald Priore, Fortunato R. :Senate agrees to the amendments of the To be second lieutenants Henry, John D. Reed, Paul R., House to a bill of the Senate of the fol Allen, Stanley C.,: 01932302. Hess, John P. 04041570. lowing title: Andrews, Wilson P., 01886686. Hoffman, Glenn F. Richardson, George A .• Basic, Nick J., 01933679. Huff, Roy P., Jr. Jr. S. 2061. An act to increase the rates of Blalock, Charlie L., 01937674. Jacobs, Talmadge J. Rinedollar, John D. basic compensation of officers and employees Boggs, Joseph C., 04011681. Janek, Floyd R. Roddy, Patrick M. in t~e field service of the Post Offiqe Depart Butler, Don A., 01888126. Janning, Thomas B., Rosie, Gerald J. me,nt. Butler, Frank C., Jr. 04004813. Roth, Robert H . Dunn, Charles H ., 01890402. Janson, Paul J. Royal, Charles M ., Evans, Ira K., Jr., 01933661. Lascola, Harry R. -

Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529018f2 No online items Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Processed by Stephan Potchatek; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Special Collections M0997 1 Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: M0997 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Stephan Potchatek Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Date (inclusive): ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: Special Collections M0997 Creator: Cabrinety, Stephen M. Extent: 815.5 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Access restricted; this collection is stored off-site in commercial storage from which material is not routinely paged. Access to the collection will remain restricted until such time as the collection can be moved to Stanford-owned facilities. Any exemption from this rule requires the written permission of the Head of Special Collections. -

”Hyökkäys Moskovaan!” – Tapaus Raid Over Moscow Suomen Ja

Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2011, s. 1–11. Toim. Jaakko Suominen et al. Tampereen yliopisto. http://www.pelitutkimus.fi/ Artikkeli ”Hyökkäys Moskovaan!” Tapaus Raid over Moscow Suomen ja Neuvostoliiton välisessä ulkopolitiikassa 1980-luvulla T E R O PA S A N E N t e r o . p a s a n e n @ j y u . fi Jyväskylän yliopisto Tiivistelmä Abstract Artikkeli käsittelee Suomen ensimmäistä poliittisesti latautunutta tietokonepe- The present article examines the first politically saturated computer and videogame likohua, joka syttyi helmikuussa vuonna 1985 MikroBitissä julkaistusta Raid over controversy in Finland, instigated by a game review of Raid over Moscow, pub- Moscow’n peliarvostelusta. Arvostelua seurannut julkinen kritiikki laukaisi tapah- lished in MikroBitti magazine in February 1985. The public criticism that followed tumaketjun, joka kärjistyi eduskuntakyselyn kautta Neuvostoliiton epäviralliseen the review triggered a chain of events that started with a written parliamentary vetoomukseen pelin markkinoinnin ja myynnin estämiseksi ja lopulta diplomaat- question, continued by an unofficial petition from the Soviet Union to restrict the tiseen protestiin neuvostovastaisesta aineistosta Suomen tiedotusvälineissä. Tässä marketing and sales of the game, and ended with a diplomatic protest towards anti- artikkelissa tarkastellaan pelikohun syntyyn ja ratkaisuun vaikuttaneita poliittisia, Soviet material and publications in Finnish media. The article focuses on political, oikeudellisia sekä kulttuurisia osatekijöitä. Artikkeli perustuu sarjaan Suomen juridical and cultural factors that contributed to the emergence and conclusion of ulkoasiainministeriön muistioita, jotka käsittelevät Neuvostoliiton vetoomusta ja the controversy. The article is based on a series of declassified Finnish Ministry for sitä seurannutta protestia. Muistioiden 25 vuoden salassapitoaika umpeutui julki- Foreign Affairs documents that dealt the Soviet petition and the protest following suuslain perusteella vuonna 2010. -

Imepilt's Newsgames As an Art Practice and Novel Form Of

AVE RANDVIIR-VELLAMO 56 Imepilt’s Newsgames as an Art Practice and Novel Form of Journalism AVE Randviir-VELLAMO The article studies the Estonian cross-media company Imepilt and its newsgames in both the Estonian and global contexts, and uses Imepilt’s games as a starting point for discussing the present state of newsgames: their strengths and weaknesses, potentials and pitfalls. The case study compares the designers’ experience in design- ing newsgames with some of the rhetoric that was used in discussing newsgames in earlier theoretical texts, and points out some inconsistencies and differences in newsgames’ theory and practice. The genre of newsgames is also placed in a his- torical context and compared with earlier media, such as editorial cartoons. Introduction Video games have been used to simulate and comment on both fictional and real political and social situations for decades. In the course of this practice, mere fiction has occasionally had some real-life consequences. In Finland during the late Cold War era, in 1985, for example, the video game Raid over Moscow (Access Software, 1984), which described an imaginary nuclear conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States of America, incited a real diplomatic scandal when the Soviet Union’s representatives filed a diplomatic protest charging anti-Soviet content in Finnish media.1 The earliest example of a video game that, at least according to some definitions, could be labelled with the contemporary title ‘newsgame’ – Save the Whales (Atari) – described an actual environmental issue by making the player protect virtual whales from nets, harpoons and radioactive waste. -

My Hero, Your Enemy

1|2013 ISSN 2084-8250 | £4.99 | PLN 16.00 1(3)|2013 MY HERO, YOUR ENEMY TEACHING HISTORY IN CENTRAL WWW.VISEGRADINSIGHT.EU WWW.VISEGRADREVUE.EU EUROPE Oldřich Tůma Mária Schmidt Juraj Marušiak Gábor Gyáni Paweł Ukielski NEIGHBORS AND SHADOWS Pavol Rankov Viktor Horváth Krzysztof Varga Memory Beyond Nations interview with Péter Balázs REPORTAGE BY JÁNOS DEME Abandoned Soviet Barracks 1 (3)|2013 CIRCULATION: 6,000 FREQUENCY: twice a year EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Wojciech Przybylski (Res Publica Nowa, PL) ECONOMY Martin Ehl (Hospodářské noviny, CZ) INTELLIGENT MIND Éva Karádi (Magyar Lettre Internationale, HU) and Marta Šimečková (www.salon.eu.sk, SK) BOOKS Marek Sečkař (Host, CZ) INTERVIEW AND COMMUNITIES Máté Zombory (HU) VISEGRAD ABROAD AND LOOKING BACK/ARTS in cooperation with Europeum (CZ) ARTS SECTION GUEST EDITOR Anna Wójcik (Res Publica Nowa, PL) LANGUAGE EDITORS C. Cain Elliot (Res Publica Nowa, PL/USA) PROOFREADING Adrianna Stansbury (PL/USA), Vera Schulmann (USA) ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR Anna Wójcik (Res Publica Nowa, PL) PHOTO EDITOR Jędrzej Sokołowski (Res Publica Nowa, PL) GRAPHIC DESIGN PUBLISHED BY Fundacja Res Publica im. H. Krzeczkowskiego ul. Gałczyńskiego 5, 00-362 Warsaw, Poland tel.: +48 22 826 05 66 ORDERS AND INQUIRIES: [email protected] WEBPAGE www.visegradinsight.eu WEBZINE UPDATED WEEKLY, EDITED BY EUROPEUM www.visegradrevue.eu ON THE COVER: Soviet military painting (Kiskunlachaza, Hungary 2012) © Tamas Dezso We kindly thank researchers working for this issue: Jędrzej Burszta, Helena Kardová, Zofia Penza, Veronka Vaspál, Antoni Walkowski. With special thanks to Magdalena Cechlovska and Dáša Čiripiová. Visegrad Insight is published by the Res Publica Foundation with the kind support of the International Visegrad Fund. -

Liste Des Jeux - Version 128Go

Liste des Jeux - Version 128Go Amstrad CPC 2542 Apple II 838 Apple II GS 588 Arcade 4562 Atari 2600 2271 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 52 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Commodore 64 7294 Family Disk System 43 Game & Watch 58 Gameboy 621 Gameboy Advance 951 Gameboy Color 502 Game Gear 277 GX4000 25 Lynx 84 Master System 373 Megadrive 1030 MSX 1693 MSX 2 146 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo 152 N64 78 NES 1822 Odyssey 2 125 Oric Atmos 859 PC-88 460 PC-Engine 291 PC-Engine CD 4 PC-Engine SuperGrafx 97 Pokemon Mini 25 Playstation 123 PSP 2 Sam Coupé 733 Satellaview 66 Sega 32X 30 Sega CD 47 Sega SG-1000 64 SNES 1461 Sufami Turbo 15 Thompson TO6 125 Thompson TO8 82 Vectrex 75 Virtual Boy 24 WonderSwan 102 WonderSwan Color 83 X1 614 X68000 546 Total 32431 Amstrad CPC 1 1942 Amstrad CPC 2 2088 Amstrad CPC 3 007 - Dangereusement Votre Amstrad CPC 4 007 - Vivre et laisser mourir Amstrad CPC 5 007 : Tuer n'est pas Jouer Amstrad CPC 6 1001 B.C. - A Mediterranean Odyssey Amstrad CPC 7 10th Frame Amstrad CPC 8 12 Jeux Exceptionnels Amstrad CPC 9 12 Lost Souls Amstrad CPC 10 1943: The Battle of Midway Amstrad CPC 11 1st Division Manager Amstrad CPC 12 2 Player Super League Amstrad CPC 13 20 000 avant J.C. Amstrad CPC 14 20 000 Lieues sous les Mers Amstrad CPC 15 2112 AD Amstrad CPC 16 3D Boxing Amstrad CPC 17 3D Fight Amstrad CPC 18 3D Grand Prix Amstrad CPC 19 3D Invaders Amstrad CPC 20 3D Monster Chase Amstrad CPC 21 3D Morpion Amstrad CPC 22 3D Pool Amstrad CPC 23 3D Quasars Amstrad CPC 24 3d Snooker Amstrad CPC 25 3D Starfighter Amstrad CPC 26 3D Starstrike Amstrad CPC 27 3D Stunt Rider Amstrad CPC 28 3D Time Trek Amstrad CPC 29 3D Voicechess Amstrad CPC 30 3DC Amstrad CPC 31 3D-Sub Amstrad CPC 32 4 Soccer Simulators Amstrad CPC 33 4x4 Off-Road Racing Amstrad CPC 34 5 Estrellas Amstrad CPC 35 500cc Grand Prix 2 Amstrad CPC 36 7 Card Stud Amstrad CPC 37 720° Amstrad CPC 38 750cc Grand Prix Amstrad CPC 39 A 320 Amstrad CPC 40 A Question of Sport Amstrad CPC 41 A.P.B. -

Computer Entertainer -August, 1986 Ziticallv Speaking

ComputerEntertainer the newsletter 12115 Magnolia Boulevard, #126, North Hollywood, Ca. 91607 ugust, 1986 Volume 5, Number 5 $3.00 r N\ HIS ISSUE... Brian Moriarty Visits Computer Entertainer p ose With Brian Moriarty, ( We always enjoy taking time out from our usual routines to meet designers and r of Wishbringer & Trinity programmers. Last month, Brian Moriarty of Infocom visited us during a press tour of \ ws Include: omando Southern California on behalf of his new Interactive Fiction Plus program, TRINITY (reviewed in this issue). This is Brian's second Infocom program. (His first, up] Cycle WISHBRINGER, holds the record as Infocom's fastest-selling program.) The 29-ycar-old i r II forC64 author has been with Infocom since 1984. Before that, he was Technical Editor of Literature n/ Analog Computing Magazine. Brian earned his B.A. in English from c Southeastern Massachusetts University. or Mulli Systems m Ending Story ../ Atari MiWorks r . or Macintosh Arithe CI 28 .lor Commodore 128 sU : Music Jor Amiga :rce hariionship Tennis Jor Intellivision only Kong series r Bros ...fr Nintendo |c & Field ,- Atari 2600 ehi: Asteroids us ..or Atari 7800 ...and more!! Brian Moriarty at the Trinity Site, where the world's first nuclear explosion took place on July 16, 1945. HIiTOP TWENTY 5 :nt Service (Mic/Co) A Confirmed Game Player I e (Fir/Co) When we ushered Brian into the hub of our workplace, we sat him in front of one of our I ima IV (Ori/Ap) Apples where a game of TRINITY was in progress. Ignoring that for the moment, he Iider Board (Acc/Co) glanced around the room, taking in the clutter of machines and software packages. -

Cyber War in Perspective: Russian Aggression Against Ukraine

cyber war in perspective: russian aggression against ukraine Cyber War in Perspective: Russian Aggression against Ukraine Edited by Kenneth Geers This publication may be cited as: Kenneth Geers (Ed.), Cyber War in Perspective: Russian Aggression against Ukraine, NATO CCD COE Publications, Tallinn 2015. © 2015 by NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, and for personal or educational use when for non-profit or non-commercial purposes, providing that copies bear a full citation. NATO CCD COE Publications Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 717 6800 Fax: +372 717 6308 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ccdcoe.org LEGAL NOTICE This publication is a product of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (the Centre). It does not necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of the Centre or NATO. The Centre may not be held responsible for any loss or harm arising from the use of information contained in this publication and is not responsible for the content of the external sources, including external websites referenced in this publication. Print: EVG Print Cover design & content layout: Villu Koskaru ISBN 978-9949-9544-4-5 (print) ISBN 978-9949-9544-5-2 (pdf) NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence The Tallinn-based NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excel- lence (NATO CCD COE) is a NATO-accredited knowledge hub, think-tank and training facility. -

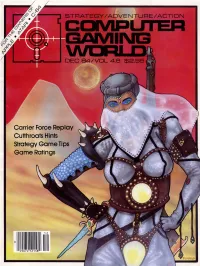

Computer Gaming World Issue

, Game Playing Aids from Computer Gaming World COSMIC BALANCE SHIPYARD DISK Contains over 20 ships that competed in the CGW COSMIC BALANCE SHIP DESIGN CONTEST. Included are Avenger, the tournament winner; Blaze, Mongoose, and MKVP6, the judge's ships. These ships are ideal for the gamer who cannot find enough competition or wants to study the ship designs of other gamers around the country. SSI's The Cosmic Balance is required to use the shipyard disk. PLEASE SPECIFY APPLE, ATARI OR C-64 VERSION WHEN ORDERING. $15.00. ROBOTWAR TOURNAMENT DISKS Diskette #1 contains the source code for the twelve entrants in CGW's Se- cond Annual Robotwar Tournament. Diskette #2 contains the seventeen en- trants in the Third Annual Robotwar Tournament. Muse Software's ROBOTWAR`" required to use these diskettes. Please specify which diskette when ordering. $15.00 each or $25.00 for both. Vol. 4 No. 6 December 1984 Features CARRIER FORCE REPLAY 10 The Midway Scenario Floyd Mathews WHEN SUPERPOWERS COLLIDE 18 An Overview Jay Selover MAIL ORDER GAMES 22 A Visit to the Classifieds John Besnard STRATEGICALLY SPEAKING 26 Our New Strategy Tips Column PANZER-JAGD 30 Review Jeff Seiken GOING Berserk 34 Galactic Gladiators Scenarios Johnny L. Wilson Departments TAKING A PEEK 6 Screen Photos & Brief Comments SCORPION'S TALE 13 Cutthroat Hints Scorpia NAME OF THE GAME 16 Should You Turn Pro? Jon Freeman COMMODORE KEY 33 Adventure Games Roy Wagner MICRO-REVIEWS 36 Return of Heracles After Pearl Dreadnoughts Breakthrough The Ardennes F-15 Strike Eagle DISPATCHES 40 Porting Dan Bunten READER INPUT DEVICE 46 GAME RATINGS 47 Access Software is well executed and will appeal to those Then you will have achieved Zenji.