Engaging with Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and Sexuality

Elyse Lemoine November 21, 2013 Game Studies I I am the Shadow, the True Self: Exploring Dungeons, Gender, Sexuality, and Identity in Persona 4 In the small, foggy town of Inaba, trouble brews as people begin to disappearing, reappearing on a TV program called the “Midnight Channel,” where they become cartoonish impersonations of themselves, broadcasting their thoughts and feelings to the world. When the fog rolls into Inaba, it brings the corpses of the missing with it. In the Japanese roleplaying game, Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 4, the player assumes the role of a silent, male protagonist, the Hero, on a mission to save as many people from the Midnight Channel as possible and figure out who the true culprit is behind these disappearances, all while managing school, studying, part-time jobs, and his social life. The game has two main methods of gameplay: one in the town of Inaba, where the player is a powerless high school student trying to manage his life, and one in the television world, where the player and his party must explore dungeons and fight Shadows using the power of Persona. These dungeons, as manifestations of the human psyche, allow players to experience and interact with characters struggling with ideas of self-perception, identity, gender, and sexuality. In Persona 3, players were given Tartarus to explore, a dungeon accessible almost every night. Balancing one’s social life along with exploring this single dungeon became the core mechanic of the game. Persona 4 followed a similar mechanic, only with smaller, individualized dungeons that appear one at a time, tied directly to the game’s main characters. -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

Theescapist 042.Pdf

putting an interview with the Garriott Games Lost My Emotion” the “Gaming at Keep up the good work. brothers, an article from newcomer Nick the Margins” series and even “The Play Bousfield about an old adventure game, Is the Thing,” you described the need for A loyal reader, Originally, this week’s issue was The Last Express and an article from games that show the consequences of Nathan Jeles supposed to be “Gaming’s Young Turks Greg Costikyan sharing the roots of our actions, and allow us to make and Slavs,” an issue about the rise of games, all in the same issue. I’ll look decisions that will affect the outcome of To the Editor: First, let’s get the usual gaming in Eastern Europe, both in forward to your comments on The Lounge. the game. In our society there are fewer pleasantries dispensed with. I love the development and in playerbase. I and fewer people willing to take magazine, read it every week, enjoy received several article pitches on the Cheers, responsibility for their actions or believe thinking about the issues it throws up, topic and the issue was nearly full. And that their actions have no consequences. and love that other people think games then flu season hit. And then allergies Many of these people are in the marketing are more than they may first appear. hit. All but one of my writers for this issue demographic for video games. It is great has fallen prey to flu, allergies or a minor to see a group of people who are interested There’s one game, one, that has made bout of forgetfulness. -

Game Narrative Review

Game Narrative Review ==================== Your name (one name, please): Ian Switaj Your school: Rochester Institute of Technology Your email: [email protected] Month/Year you submitted this review: December 2013 ==================== Game Title: Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 4 Platform: Playstation 2 Genre: Role-playing, Social simulation Release Date: July 10, 2008 (JP) / December 9, 2008 (NA) Developer: Atlus Publisher: Atlus Game Writer/Creative Director/Narrative Designer: Katsura Hashino (Director), Azusa Kido (Scenario and Social Link Planning Leader), Yuichiro Tanaka and Akira Kawasaki (Scenario Writer), US Localization: Martin Britton, James Kuroki, Mai Namba, and Jensen Kamiya (Translator), Nich Maragos (Lead Editor) Overview Persona 4 is a Japanese Roleplaying Game (JRPG) in which a group of high school students are trying to capture the culprit responsible for a chain of murders and kidnappings that began plaguing their town starting April 11, 2011. In the town of Inaba a rumor is going around that by looking at a TV screen at 12:00 AM on a rainy night the face of the viewer’s soulmate will be revealed. The player takes control of a second year high school student who is forced to move to the countryside and live with his uncle’s family for an entire year while his parents are overseas on business and, as a result, becomes inexplicitly involved in the supernatural chain of murders. Victims that are thrown into the TV are attacked and ultimately killed by their Shadows, or manifestations of their repressed psyches, and are found dead in the human world on days of fog. The protagonist and his team of Persona users, must brave the horrors and unknowns of the mysterious TV world populated by Shadows, beings that represent the generally negative emotions and psyches of mankind, in order to seek the truth behind the chain of mysterious murders and their connections to this mysterious rumor, rescue the victims, and uncover the identity of the culprit responsible. -

Sciences Du Jeu, 5

Sciences du jeu 5 | 2016 Jeux traditionnels et jeux numériques : filiations, croisements, recompositions Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/sdj/544 DOI : 10.4000/sdj.544 ISSN : 2269-2657 Éditeur Laboratoire EXPERICE - Centre de Recherche Interuniversitaire Expérience Ressources Culturelles Education Référence électronique Sciences du jeu, 5 | 2016, « Jeux traditionnels et jeux numériques : filiations, croisements, recompositions » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 20 février 2016, consulté le 18 mars 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/sdj/544 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/sdj.544 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 18 mars 2020. La revue Sciences du jeu est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Dossier thématique Correspondances et contrastes entre jeux traditionnels et jeux numériques Delphine Buzy-Christmann, Laurent Di Filippo, Stéphane Goria et Pauline Thévenot Rejouer le récit dans différentes adaptations ludiques de l’univers de J.R.R. Tolkien Simon Dor La conception de jeux en réalité alternée reliés aux séries télévisées. La scénarisation de fictions ludiques hybrides, entre jeu traditionnel et jeu numérique Marida Di Crosta et Ana Chantôme Un ordinateur champion du monde d’Échecs : histoire d’un affrontement homme-machine Lisa Rougetet Les jeux vidéo compétitifs au prisme des jeux sportifs : du sport au sport électronique Nicolas Besombes L’emploi des jeux dans l’enseignement -

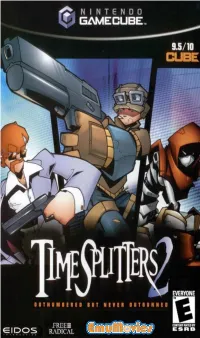

TIMESPLITTERS 2Player(S) Inserted Into a Memory Card Slot (A/B)

TS2 GC final 9/23/02 11:05 AM Page ii WARNING - Electric Shock FPO To avoid electric shock when you use this system: Inside Front Cover Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. Remove before printing Make sure that the AC adapter cord is fully inserted into the wall outlet or See the “TS2 GC ins cov.eps” document extension cord. Always carefully disconnect all plugs by pulling on the plug and not on the cord. for the actual page Make sure the Nintendo GameCube power switch is turned OFF before removing the AC adapter cord from an outlet. CAUTION - Motion Sickness Playing video games can cause motion sickness. If you or your child feel dizzy or nauseous when playing video games with this system, stop playing and rest. Do not drive or engage in other demanding activity until you feel better. CAUTION - Laser Device The Nintendo GameCube is a Class 1 laser product. Do not attempt to disassemble the Nintendo GameCube. Refer servicing to qualified personnel only. Caution - Use of controls or adjustments or procedures other than those specified herein may result in hazardous radiation exposure. CONTROLLER NEUTRAL POSITION RESET If the L or R Buttons are pressed or the Control Stick or C Stick are moved out of neutral position when the power is turned ON, those positions will be set as the neutral position, causing incorrect game control during game play. To reset the controller, release all buttons and sticks to allow them to return to the L Button R Button correct neutral position, then hold down the X, Y and START/PAUSE Buttons simultaneously for 3 seconds. -

Gaming Flashback: Timesplitters 2 in Or Modern Era of Gaming, Where Yearly Call of Duty Releases Are Hotly Awaited and the Lates

Gaming Flashback: TimeSplitters 2 In or modern era of gaming, where yearly Call of Duty releases are hotly awaited and the latest Halo release can be the backbone of the latest console generation, it’s hard to believe that the first- person shooter genre was once regarded with apprehension. In truth, this mode of gaming is barely a decade old, in its popular form. Back in the mid-2000s, when I was passing from junior high to high school and really getting my feet wet in video games, as a whole, I used to scoff at the genre. Sure, there were a few fun outliers, and a couple of rounds of Goldeneye 007 were good during a birthday party, but I could see no way in which they could ever supersede my beloved RPGs or RTS games. The party game corner was already fully claimed by Super Smash Bros, Mario Kart, and fighting games like Soul Calibur 2 – perish the thought of some run-and-gun nonsense ever taking their place! But naïve I was, dear readers! How wrong I could be! Because it only took one party for a friend of a friend to show me the light; and the savior was called TimeSplitters2. Released in October of 2002, this ridiculous FPS was the smash sequel to an early PS2 title created by a splinter team from the legendary Rare studios, henceforth known as Free Radical. Combining their technical know-how from the aforementioned Goldeneye for the N64 and a wry British comedy, TimeSplitters 2 lets players kill each other and enemy bots with a variety of weapons as a plethora of characters, from throughout time, space, and sanity. -

An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers Cultural Analysis and Social Theory 8-2018 Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games Jessica Kathryn Needham Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Needham, Jessica Kathryn, "Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games" (2018). Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers. 6. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cultural Analysis and Social Theory at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering player agency and paratexts: An analysis and expansion of queerbaiting in video games by Jessica Kathryn Needham Honours Rhetoric and Professional Writing, Arts and Business, University of Waterloo, 2016 Major Research Paper Submitted to the M.A. in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University 2018 © Jessica Kathryn Needham 2018 1 Abstract Queerbaiting refers to the way that consumers are lured in with a queer storyline only to have it taken away, collapse into tragic cliché, or fail to offer affirmative representation. Recent queerbaiting research has focused almost exclusively on television, leaving gaps in the ways queer representation is negotiated in other media forms. -

Game Developer Power 50 the Binding November 2012 of Isaac

THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE VOL19 NO 11 NOVEMBER 2012 INSIDE: GAME DEVELOPER POWER 50 THE BINDING NOVEMBER 2012 OF ISAAC www.unrealengine.com real Matinee extensively for Lost Planet 3. many inspirations from visionary directors Spark Unlimited Explores Sophos said these tools empower level de- such as Ridley Scott and John Carpenter. Lost Planet 3 with signers, artist, animators and sound design- Using UE3’s volumetric lighting capabilities ers to quickly prototype, iterate and polish of the engine, Spark was able to more effec- Unreal Engine 3 gameplay scenarios and cinematics. With tively create the moody atmosphere and light- multiple departments being comfortable with ing schemes to help create a sci-fi world that Capcom has enlisted Los Angeles developer Kismet and Matinee, engineers and design- shows as nicely as the reference it draws upon. Spark Unlimited to continue the adventures ers are no longer the bottleneck when it “Even though it takes place in the future, in the world of E.D.N. III. Lost Planet 3 is a comes to implementing assets, which fa- we defi nitely took a lot of inspiration from the prequel to the original game, offering fans of cilitates rapid development and leads to a Old West frontier,” said Sophos. “We also the franchise a very different experience in higher level of polish across the entire game. wanted a lived-in, retro-vibe, so high-tech the harsh, icy conditions of the unforgiving Sophos said the communication between hardware took a backseat to improvised planet. The game combines on-foot third-per- Spark and Epic has been great in its ongoing weapons and real-world fi rearms. -

A Clash Between Game and Narrative

¢¡¤£¦¥¦§¦¨©§ ¦ ¦¦¡¤¥¦ ¦¦ ¥¦§ ¦ ¦ ¨© ¦¡¤¥¦¦¦¦¡¤¨©¥ ¨©¦¡¤¨© ¦¥¦§¦¦¥¦ ¦¦¦ ¦¦¥¦¦¨©§¦ ¦!#" ¦$¦¥¦ %¤©¥¦¦¥¦©¨©¦§ &' ¦¦ () ¦§¦¡¤¨©¡*¦¡¤¥ ,+- ¦¦¨© ./¦ ¦ ¦¦¦¥ ¦ ¦ ./¨©¡¤¥ ¦¦¡¤ ¦¥¦0#1 ¦¨©¥¦¦§¦¨©¡¤ ,2 ¦¥¦ ¦£¦¦¦¥ ¦0#%¤¥¦$3¦¦¦¦46555 Introduction ThisistheEnglishtranslationofmymaster’sthesisoncomputergamesandinteractivefiction. Duringtranslation,Ihavetriedtoreproducemyoriginalthesisratherfaithfully.Thethesiswas completedinFebruary1999,andtodayImaynotcompletelyagreewithallconclusionsorpresup- positionsinthetext,butIthinkitcontinuestopresentaclearstandpointontherelationbetween gamesandnarratives. Version0.92. Copenhagen,April2001. JesperJuul Tableofcontents INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................... 1 THEORYONCOMPUTERGAMES ................................................................................................................................ 2 THEUTOPIAOFINTERACTIVEFICTION...................................................................................................................... 2 THECONFLICTBETWEENGAMEANDNARRATIVE ...................................................................................................... 3 INTERACTIVEFICTIONINPRACTICE........................................................................................................................... 4 THELUREOFTHEGAME.......................................................................................................................................... -

Kalle Kotipsykiatri -Tietokone- Ohjelma Tekoälyn Popularisoijana 1980-Luvulla

THS Tekniikan Waiheita ISSN 2490-0443 Tekniikan Historian Seura ry. 37. vuosikerta:3 2019 https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen Jaakko Suominen https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1352-7699 To cite this article: Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen, ”'Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa': Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokoneohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-lu- vulla” Tekniikan Waiheita 37, no. 3 (2019): 6–30. https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 To link to this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski1, Markku Reunanen2 & Jaakko Suominen3 Tekoälyä koskevalla vilkkaalla julkisuuskeskustelulla on oma monipuolinen taustahistoriansa. Artikke- lissa käsitellään Pekka Tolosen luoman Kalle kotipsykiatri -ohjelman vaiheita 1980-luvun tietokoneleh- distössä. Kalle kotipsykiatri tunnetaan varhaisena esimerkkinä tekoälyä simuloivasta keskusteluohjel- masta, jonka Commodore 64 -käännösversion koodivirheitä korjailtiin yli vuoden ajan kotitietokoneisiin erikoistuneessa MikroBitti -lehdessä. Johdanto Tekoälyltä koskevalta keskustelulta voi tuskin välttyä nykyään missään. Tekoäly esiintyy uu- tisissa, poliittisissa puheissa, mediajulkisuudessa sekä ihmisten kasvokkais- ja nettikeskuste- luissa. Tekoälyllä viitataan muun muassa robotteihin, erilaisiin digitaalisiin -

Download Resume

Objective A high performing, team-player in art direction, web design, and award winning computer animation, I am seeking a challenging full time opportunity to direct projects where my advanced skills, education, and 15+ years of professional experience can be fully utilized. Nicole Tostevin Summary of Qualifications Contact • Art Direction • Ecommerce Experience 415.203.0721 • Product Design • eLearning Educational Design [email protected] • Integrated Brand Design • Animatics • UI/UX Design • User Research Online Portfolio • Storyboarding • Usability Testing www.redheadart.com • WordPress Design/Development • User Stories / Journeys / Flows • Responsive Web Design • Interviews and Surveys • Information Graphics/Animation • Sketch |Wireframes • Social Media Design • Interactive Prototyping • Multimedia Storytelling • Low/High Fidelity Mockups • Graphic Design | Illustration • Style Guides • Animation | Motion Graphics • Mood Boards Education • CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF THE ARTS M.F.A. Experimental Animation, Graduate Film School, Valencia, CA • SAN FRANCISCO ART INSTITUTE 1/3 of M.F.A. work in Graduate Video, Computer Art, Performance Art • POMONA COLLEGE B.F.A. Art Major, Claremont Colleges, Claremont, CA Computer & Technology Skills • Adobe Creative Suite • Principle • Sketch | Zeplin • InVision • Adobe Experience Design • Framer • Adobe Photoshop • Keynote | PowerPoint • Adobe Illustrator • Google Slides • After Effects / Cinema 4D • Adobe Captivate • Premiere Pro • Docebo LMS • Adobe Animate • Google Web Designer • Flash |