Ritual Calendar. Change in the Conceptions of Time and Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanuman Chalisa.Pdf

Shree Hanuman Chaleesa a sacred thread adorns your shoulder. Gate of Sweet Nectar 6. Shankara suwana Kesaree nandana, Teja prataapa mahaa jaga bandana Shree Guru charana saroja raja nija You are an incarnation of Shiva and manu mukuru sudhari Kesari's son/ Taking the dust of my Guru's lotus feet to Your glory is revered throughout the world. polish the mirror of my heart 7. Bidyaawaana gunee ati chaatura, Baranaun Raghubara bimala jasu jo Raama kaaja karibe ko aatura daayaku phala chaari You are the wisest of the wise, virtuous and I sing the pure fame of the best of Raghus, very clever/ which bestows the four fruits of life. ever eager to do Ram's work Buddhi heena tanu jaanike sumiraun 8. Prabhu charitra sunibe ko rasiyaa, pawana kumaara Raama Lakhana Seetaa mana basiyaa I don’t know anything, so I remember you, You delight in hearing of the Lord's deeds/ Son of the Wind Ram, Lakshman and Sita dwell in your heart. Bala budhi vidyaa dehu mohin harahu kalesa bikaara 9. Sookshma roopa dhari Siyahin Grant me strength, intelligence and dikhaawaa, wisdom and remove my impurities and Bikata roopa dhari Lankaa jaraawaa sorrows Assuming a tiny form you appeared to Sita/ in an awesome form you burned Lanka. 1. Jaya Hanumaan gyaana guna saagara, Jaya Kapeesha tihun loka ujaagara 10. Bheema roopa dhari asura sanghaare, Hail Hanuman, ocean of wisdom/ Raamachandra ke kaaja sanvaare Hail Monkey Lord! You light up the three Taking a dreadful form you slaughtered worlds. the demons/ completing Lord Ram's work. -

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations Tonight we will be doing chapter 10 of the Bhagavad Gita, Vibhuti Yoga, The Yoga of Divine Emanations. But first I want to talk about the nature of the journey. For most of us Westerners this aspect of the Gita is not available to us. Very few people in the West open up to God, to the collective consciousness, in the experiential way that is being revealed here. Most spiritual teachings have more to do with the development of the psychic intelligence and its relationship to truth. Vibhuti Yoga is truly devotional. A vast majority of people have a devotional relationship or feeling for whatever God or Allah or Zoroaster represents. It comes from something in our human nature that is transferring onto an idea, from the human collective consciousness, and is different from what we will be talking about today. (2:00) Vibhuti Yoga is a direct revelation from the universe to the individual. What we might call devotion is absolutely felt, but of a completely different order than what we would call religious devotion or the fervor that occurs with born again Christians or with people that are motivated from their vital for this passionate relationship, for this idea of God. That comes from the higher heart, the higher vital, the part of our human nature that is rising up from our focus on our relationships and attachments and identifications associated with community and society. It is a part of us that lifts to a possibility. It is to some extent associated with what I call the psychic heart. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

Akshaya Tritiya Special Puja

Hindu Temple & Cultural Center of WI American Hindu Association 2138 South Fish Hatchery Road, Fitchburg, WI 53575 AHA Shiva Vishnu Temple Akshaya Tritiya Special Puja & Lalitha Sahasranamam Recital May 2, 2014 ~ Friday-6:30pm to 8pm Goddess Maha Lakshmi & Lord Kubera Abishekam & Puja SPONSORSHIP: $108 for the 1g Laxmi* gold coin Puja conducted by Priest Madhavan Bhattar Venue: 2138 South Fish Hatchery Rd, Fitchburg, WI 53575 Prasad will be served at the temple Akshaya Trithiya : Akshaya (meaning Never-Ending, or that which never diminishes) Trithiya (the Third Day of Shuklapaksha(Waxing Moon)) in the Vishaka Month is regarded as the day of eternal success. The Sun and Moon are both in exalted position, or simultaneous at their peak of brightness, on this day, which occurs only once every year. This day is widely celebrated as Parusurama Jayanthi, in honor of Parusurama – the sixth incarnation of Lord Maha Vishnu. Lord Kubera, who is the keeper of wealth for Goddess Maha Lakshmi, is said to himself pray to the Goddess on this day. Lord maha Vishnu and his Avatars, Goddess Maha Lakshmi and Lord Kubera are worshipped on Akshaya Trithiya Day. Veda vyasa began composing Mahabharatha on this day. Since Divine Mother Goddess Maha Lakshmi is intensely and actively manifest and due to the mystical nature of our Temple, all Pirthurs(all our ancestors’ subtle and causal bodies) congregate at our Temple. All these Ethereal beings are pleased and will gain higher cosmic energy when we offer pujas on their behalf. Pitru Tarpanam can be done on any day of the year depending on the day one’s ancestors passed away, but performing it during Mahalaya Amavasya and Akshaya Trithiya will multifold benefits. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha. -

Yakshas, Yakshis and Other Demi-Goddesses of Mathura

THE Y AKSHAS, NAGAS AND OTHER REGIONAL CULTS OF MATI-IURA The architectural remains from Mathura discussed, are a good indicator of the scale of organisation and popularity of the multiple religious cults that existed in the region, but there were possibly many other local sects and practices that flourished around the region that did not have any monumental architecture associated with them. The cult of the numerous Yakshas and the local village gods and goddesses are some of them, and yet their popularity in the region rivalled the major sects like Buddhism and lainism at Mathura. This chapter discusses these popular cults of the region and their representation in the sculptural imagery at Mathura. The repertoire of Naga and Yaksha imagery at Mathura is extremely diverse, and they occur both as independent cults in their own right, displaying certain iconographic conventions as is discerned from the sculptural evidencc, or as part of the larger Buddhist and laina pantheons, in which they are accorded a variety of roles and are depicted variously. An interesting fact to note is that these regional cults are dispersed quite evenly in the region, and run parallel to most of the Buddhist and laina sculptures. The beginnings of these cults can be traced back to the 2nd century B.C., as exemplified by the colossal Parkham Yaksha, or perhaps even earlier if one takes into account the various terracotta figurines that occur as early as 400 H.C. They not only coexist and flourish in Mathura, along with the many other religious sects, but also perhaps outlive the latter, continuing to be an inevitable part of the local beliefs and practices of the region in the present times. -

Nectar Lyrics

NECTAR TRACK 1: RADHA REMIX Bolo Radha Ramana Hari Bol Sing to Lord Hari, who is playful and amorous, dear to His beloved consort Radha, the embodiment of love and bliss. Radha, Radha, Radha, Radha Radhe, Radhe, Radhe, Radhe, Bolo Shree Krishna Govinda Hare Murare Sing to Krishna, cow herding boy, incarnation of Lord Vishnu, holder of the flute, emanating waves of Supreme Consciousness and Light. Singing to Radha, we become Radha, the Goddess, the most intimate companion of lord Krishna, the manifestation of divine love. We wear the mantel of Radha’s “Rasa”, or nectar, and envelope ourselves in Her moods of longing and union, longing and union. We meet our beloved late at night in the grove of our heart, and we lose ourselves in that meeting. Radhe Radhe. The word resonates from every street corner, every man, and every woman in the town of Vrindavan, where Radha eternally lives. Forgetting our names, and the bindings of our lives and personalities, upon hearing Krishna’s flute we instantly transform into Radha, the beloved of our beloved, the secret lover within. TRACK 2: OPENING THE GATES Ram Ram Siya Ram Siya Ram Mei Saba Jaga Janee Karahun Pranama Jyoda Juga Pani Invoking the Divine Couple. Goddess Sita and Lord Ram; whose very name is most sacred and pure Hail to the Divine couple, Goddess Sita and Lord Ram who dwell in the entire universe and all of creation; eternally luminous and shining as celestial moonlight. We humbly bow with folded palms at Your lotus feet. An offering, an invocation, a supplication, that the gates of the holy temple within be opened, and that we may enter. -

Navaratri Ganeshanjali 06.Qxd

Navaratri ganeshanjali 18. print.qxp_Navaratri ganeshanjali 18.qxd 8/7/18 5:44 PM Page 1 G A N E Š Ã N J A L I Šri Devi Nava-Rãtri Mahotsavam Deepãvali / Šri Mahã Lakshmi Mahotsavam Skanda Shashti Mahotsavam Tuesday, October 9 th thru Friday, November 16 th , 2018 Šri Mahã Lakshmi THE HINDU TEMPLE SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA, NY Šri Mahã Vallabha Ganapati Devasthãnam 45-57 Bowne Street, Flushing, NY 11355-2202 Tel: (718) 460-8484 ext.112 s Fax: (718) 461-8055 email: [email protected] s http://nyganeshtemple.org VOL 41-18 No. 5P s 8 Issues per Year Navaratri ganeshanjali 18. print.qxp_Navaratri ganeshanjali 18.qxd 8/7/18 5:44 PM Page 2 ŠRI DEVI NAVA-RÃTRI MAHOTSAVAM Tuesday, October 9 th thru Thursday, October 18 th , 2018 LAKSHÃRCHANA FOR ŠRI PÃRVATI Tuesday, October 9 th thru Wednesday, October 17 th , 2018 10:30 AM, 11:00 AM & 11:30 AM Šri Pãrvati Lakshãrchana 7:15 PM Šri Pãrvati Abhishekam ŠRI DURGÃ POOJA Tuesday, October 9 th thru Thursday, October 11 th , 2018 8:00 AM Devi Suprabhãtam. 8:30 AM Šri Mahã Ganapati Pooja, Chandi Navãvarana Pooja, Lalitã Trišatinãma Pooja. 8:30 AM Šri Durgã Homam. 9:30 AM Šri Durgã Abhishekam, Sahasranãma Pooja. Wednesday, October 10th, 2018 Scheduled Šri Saraswati Abhishekam will be at 9:30 AM instead of 6:00 PM followed by Saraswati Sahasranãma Archana ŠRI GURU PRAVEŠAM Thursday, October 11 th , 2018 A A Libra Jupiter moving from Tula Rãši (Libra) to Vrischika Rãši (Scorpio) Scorpio 8:30 AM Šri Guru Homam. -

Simple Hanuman Homa Visit for More Manuals

` ïI mhag[pty e nm> ` ïI gué_yae nm> ` \i;_yae nm> Simple Hanuman Homa Visit for more manuals: https://EasyHoma.org Introduction Lord Hanuman is personification of perfect wisdom, bravery and humility. He protects devotess from evil forces and gives wisdom, bravery and humility. His homa can be done every day or every Tuesday (or weekend). Preparation Find a standard homa kunda or simply a small vessel/utensil made of copper/silver/bronze/steel, in square/circular/rectangular shape. Even if it was used for cooking earlier, it's ok. Clean it thoroughly, dry it and use it. We'll simply call it "homa kunda" in this writeup. Find some ghee (clarified butter). If not available, use sesame oil or some other oil. Find a copper/silver/steel cup/tumbler/vessel to keep melted ghee. Find a copper/silver/steel spoon for offering ghee. Find another tumbler and spoon for water. Keep a matchbox and camphor (if available) ready. If possible, get some dry coconut (copra) halves at a nearby store and make small pieces (roughly 1 inch x 1 inch). If not, collect some fallen dry twigs from nearby trees (or other firewood). If you have dried cowdung pieces, you can use those too. If you have black/brown/white sesame seeds and any unsalted plain nuts (e.g. cashews, almonds etc), you can use them too. Some Precautions Do NOT consume meat or alcohol or drugs on the previous day. Sleep well and get up early on the day of homa. Take bath and wear clean clothes that you feel comfortable in (no need for traditional clothes if they make you uncomfortable, as being in a calm state of mind is more important than externalities). -

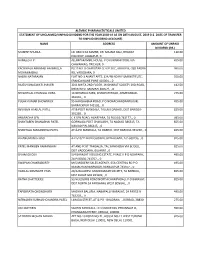

Name Address Amount of Unpaid Dividend (Rs.) Mukesh Shukla Lic Cbo‐3 Ka Samne, Dr

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2018‐19 AS ON 28TH AUGUST, 2019 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 110.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 495.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 KACHWALA ABBASALI HAJIMULLA PLOT NO. 8 CHAROTAR CO OP SOC, GROUP B, OLD PADRA 990.00 MOHMMADALI RD, VADODARA, 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 550.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 412.50 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 SEVANTILAL CHUNILAL VORA 14 NIHARIKA PARK, KHANPUR ROAD, AHMEDABAD‐ 275.00 381001, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 495.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 REVABEN HARILAL PATEL AT & POST MANDALA, TALUKA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐ 825.00 391230, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 495.00 SHANTABEN SHANABHAI PATEL GORWAGA POST CHAKLASHI, TA NADIAD 386315, TA 825.00 NADIAD PIN‐386315, , 0 SHANTILAL MAGANBHAI PATEL AT & PO MANDALA, TA DABHOI, DIST BARODA‐391230, , 0 825.00 B HANUMANTH RAO 4‐2‐510/11 BADI CHOWDI, HYDERABAD, A P‐500195, , 0 825.00 PATEL MANIBEN RAMANBHAI AT AND POST TANDALJA, TAL.SANKHEDA VIA BODELI, 825.00 DIST VADODARA, GUJARAT., 0 SIVAM GHOSH 5/4 BARASAT HOUSING ESTATE, PHASE‐II P O NOAPARA, 495.00 24‐PAGS(N) 743707, , 0 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 495.00