Conceptualizing Noongar Song 93

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal History Journal

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Editor Shino Konishi, Book Review Editor Luise Hercus, Copy Editor Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, are welcomed. Subjects include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, archival and bibliographic articles, and book reviews. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, Coombs Building (9) ANU, ACT, 0200, or [email protected]. -

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Fact Sheet Number 14

FACT SHEET No. #4 DEEP TIME AND DRAGON DREAMING: THE SUSTAINABLE ABORIGINAL SPIRITUALITY OF THE SONG LINES, FROM CELEBRATION TO DREAMING John Croft update 28th March 2014 This Factsheet by John Croft is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at [email protected]. ABSTRACT: It is suggested that in a culture that is suicidal, to get a better understanding of what authentic sustainability is about requires us to see through the spectrum of a different culture. Australian Aboriginal cultures, sustainable for arguably 70,000 years, provide one such useful lens. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................2 AN INTRODUCTION TO ABORIGINAL CULTURE ............................................................................... 4 THE UNSUSTAINABILITY OF CIVILISED CULTURES ........................................................................... 6 DREAMING: AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF TIME? ............................................................................. 10 ABORIGINAL DREAMING, DEEP ECOLOGY AND THE ECOLOGICAL SELF ....................................... 17 DREAMING AND SUSTAINABILITY ................................................................................................. 21 DISCOVERING YOUR OWN PERSONAL SONGLINE ......................................................................... 24 _____________________________________________________________________________________D -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages

Endangered Songs and Endangered Languages Allan Marett and Linda Barwick Music department, University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia [[email protected], [email protected]] Abstract Without immediate action many Indigenous music and dance traditions are in danger of extinction with It is widely reported in Australia and elsewhere that songs are potentially destructive consequences for the fabric of considered by culture bearers to be the “crown jewels” of Indigenous society and culture. endangered cultural heritages whose knowledge systems have hitherto been maintained without the aid of writing. It is precisely these specialised repertoires of our intangible The recording and documenting of the remaining cultural heritage that are most endangered, even in a traditions is a matter of the highest priority both for comparatively healthy language. Only the older members of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Many of the community tend to have full command of the poetics of our foremost composers and singers have already song, even in cases where the language continues to be spoken passed away leaving little or no record. (Garma by younger people. Taking a number of case studies from Statement on Indigenous Music and Performance Australian repertories of public song (wangga, yawulyu, 2002) lirrga, and junba), we explore some of the characteristics of song language and the need to extend language documentation To close the Garma Symposium, Mandawuy Yunupingu to include musical and other dimensions of song and Witiyana Marika performed, without further performances. Productive engagements between researchers, comment, two djatpangarri songs—"Gapu" (a song performers and communities in documenting songs can lead to about the tide) and "Cora" (a song about an eponymous revitalisation of interest and their renewed circulation in contemporary media and contexts. -

Teachers' Notes for Secondary Schools

artback nt: arts development and touring presents teachers’ notes for secondary schools teachers’ notes for secondary schools table of contents History - Djuki Mala [The Chooky Dancers] pg 3 Activity - Djuki Mala Zorba the Greek on YouTube pg 3 Activity - Online video - Elcho Island and The Chooky Dancers pg 3 Activity - Traditional dance comparison pg3 Home - Elcho Island pg 4 History pg 5 Activity - Macassar research pg 5 Activity - ‘Aboriginal’ vs ‘Indigenous’ pg 5 Activity - Gurrumul research pg 6 Activity - ‘My Island Home’ pg 6 Activity - Film: ‘Big Name No Blankets’ pg 6 Community pg 7 Activity - Elcho Island: Google Earth pg 7 Yolngu Culture pg 8 Activity - Film: ‘Yolgnu Boy’ + questions pg 8 Activity - Film: ‘Ten Canoes’ pg 9 Activity - Documentary: ‘Balanda and the Bark Canoes’ pg 9 Activity - Yolgnu culture clips online pg 9 Clans and Moieties pg 9 Activity - Clans and moieties online learning pg 9 Language pg 10 Activity - Yolngu greetings pg 10 Useful links and further resources pg 11 usage notes These notes are intended as a teaching guide only. They are suitable for high school students at different levels and teachers should choose from the given activities those that they consider most suitable for different year groups. The notes were developed by Mary Anne Butler for Artback NT: Arts Development and Touring. Thanks to Stuart Bramston, Shepherdson College, Jonathan Grassby, Linda Joy and Joshua Bond for their assistance. teachers’ notes page 2 of 11 History - Djuki Mala [T he Chooky Dancers] In 2007, on a basketball court in Ramingining, a group of Elcho Island dancers calling themselves the Chooky Dancers choreographed and performed a dance routine to the tune of Zorba the Greek. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

Ngapartji Ngapartji Ninti and Koorliny Karnya

Ngapartji ngapartji ninti and koorliny karnya quoppa katitjin (Respectful and ethical research in central Australia and the south west) Jennie Buchanan, Len Collard and Dave Palmer 32 Ngapartji ngapartji ninti and koorliny karnya quoppa katitjin (Respectful and ethical research in central Australia and the south west) Jennie Buchanan Len Collard Murdoch University University of Western Australia [email protected] [email protected] Dave Palmer Murdoch University [email protected] Keywords: marlpara (friend/colleague), ngapartji ngapartji (reciprocity), birniny (digging and inquiring), kulini (listening), dabakarn dabakarn (going slowly) Abstract This paper is set out as a conversation between three people, an Indigenous person and two non-Indigenous people, who have known and worked with each other for over 30 years. This work has involved them researching with communities in central Australia and the south west of Western Australia. The discussion concerns itself with ideas and practices that come from three conceptual traditions; English, Noongar and Pitjantjatjara to talk about how to build ngapartji ngapartji (“you give and I give in return”, in Pitjantjatjara), karnya birit gnarl (respectful and kind ways of sweating/working with people, in Noongar), between marlpara (“colleagues”, in Pitjantjatjara) and involving warlbirniny quop weirn (singing out to the old people, in Noongar). Kura katitj (Introduction and background) The history of outsiders carrying out research with Indigenous Australians is long and often vexed. To say that Indigenous communities do not often benefit from the work of researchers is perhaps an understatement. Although approved by the ethical protocols of universities, much research that is undertaken “on” Indigenous people, Indigenous lands and Indigenous knowledge maintains the longstanding model of “excavating” information, artifacts and insights. -

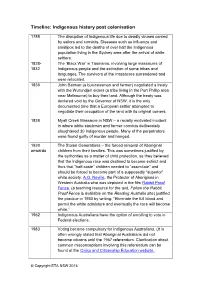

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

National Environmental Science Program Indigenous Partnerships 2020 National Environmental Science Program Indigenous Partnerships 2020

National Environmental Science Program Indigenous partnerships 2020 National Environmental Science Program Indigenous partnerships 2020 This publication is available at environment.gov.au/science/nesp. Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment GPO Box 858 Canberra ACT 2601 Copyright Telephone 1800 900 090 Web awe.gov.au The Australian Government acting through the Department of Agriculture, Water and © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 the Environment has exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the Department of Agriculture, Ownership of intellectual property rights Water and the Environment, its employees and advisers disclaim all liability, including Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this liability for negligence and for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the person as a result of accessing, using or relying on any of the information or data in this Commonwealth). publication to the maximum extent permitted by law. Creative Commons licence Acknowledgements All material in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 The authors thank the National Environmental Science Program research hubs for their International Licence except content supplied by third parties, logos and the input. Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Inquiries about the licence and any use of this document should be emailed to [email protected] Cataloguing data Keep in touch This publication (and any material sourced from it) should be attributed as: Science Partnerships 2020, National Environmental Science Program Indigenous partnerships 2020, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Canberra, November. -

Walakandha Wangga

Walakandha Wang ga Archival recordings by Marett et al. Notes by Marett, Barwick & Ford 1 THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Ambrose Piarlum dancing wangga at a Wadeye circumcision ceremony, 1992. Photograph by Mark Crocombe, reproduced with the permission of Wadeye community. Walakandha Wangga THE INDIGENOUS MUSIC OF AUSTRALIA CD6 Archival recordings by Allan Marett, with supplementary recordings by Michael Enilane, Frances Kofod, William Hoddinott, Lesley Reilly and Mark Crocombe; curated and annotated by Allan Marett and Linda Barwick, with transcriptions and translations by Lysbeth Ford. Dedicated to the late Martin Warrigal Kungiung, Marett’s first wangga teacher Published by Sydney University Press © Recordings by Allan Marett, Michael Enilane, William Hoddinott, Frances Kofod, Lesley Reilly, & Mark Crocombe 2016 © Notes by Allan Marett, Linda Barwick and Lysbeth Ford 2016 © Sydney University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this CD or accompanying booklet may be reproduced or utilised in any way or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher. Sydney University Press, Fisher Library F03, University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Web: sydney.edu.au/sup ISBN 9781743325292 Custodian statement This music CD and booklet contain traditional knowledge of the Marri Tjavin people from the Daly region of Australia’s Top End. They were created with the consent of the custodians. Dealing with any part of the music CD or the texts of the booklet for any purpose that has not been authorised by the custodians is a serious breach of the customary laws of the Marri Tjavin people, and may also breach the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth).