Open & Online: Wales, Higher Education and Emerging Modes Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

07501022017 Email: [email protected]

[email protected] @LlaisLlandyrnog The August Bank Holiday was very quiet this year, without the usual hustle and bustle around the village hall. The annual event is a great opportunity for the residents of Llandyrnog and its environs to get together purely to socialise, as well as to admire the wonderful produce and crafts exhibited. However, there has been an excellent response to an appeal for photographs in lieu of the show. This is a wonderful colourful version of the Llais, which is also available in print for the first time since March. Condolences: Bryn Bellis, Erw Frân, has Diamond Wedding Anniversary passed away following a long illness. We send Gwyn and Valerie were married at St Mary’s our sincerest sympathy to Carol and all the Church, Denbigh 27th August 1960, and the family. Our condolences also to Sylvia and reception was held at the Crown Hotel. They the family of the late Bill Evans, Fforddlas. have lived in Llandyrnog all their married We also send our regards to David and life. Gwyn ‘Dŵr’ retired from the Waterboard Margaret Jones, Hafan Dawel on the loss of many years ago and Valerie retired from the David’s sister, Eira Reece Jones. Infirmary. We would all like to wish you a very happy Get well soon: to Les Ward after his stay at anniversary and hope you have a wonderful Ysbyty Glan Clwyd. day. Love from all the family. The Kinmel Arms has reopened its doors since Wednesday 5th August. Obviously Golden wedding celebration: things feel a little different and there has Congratulations to Aeron and Menna Ellis, been hard work to put safety measures in Gader Goch, on celebrating their golden place along with a few ‘rules’. -

The Good Guide

Choose from more than 600 Universities and Colleges FOR 2019/2020 THE GOOD APPLIC ANTS UNIVERSITIES ION SP AT EC C IA U L D GUIDE I S £3.99 | AUTUMN 2018 | independentschoolparent.com E T S T N E D N E P E I N D Open days CAMBRIDGE YOUR YORK MANCHESTER ESSENTIAL BIRMINGHAM OXFORD GUIDE ABERYSTWYTH ST ANDREWS CARDIFF NOTTINGHAM KING’S COLLEGE ACM EDINBURGH EXETER DURHAM UCL SOUTHAMPTON NEWCASTLE WARWICK BRISTOL LEEDS READING EAST ANGLIA LIVERPOOL LSE KENT HULL GOLDSMITHS SHEFFIELD How to choose the right GLASGOW BATH BANGOR NORTHUMBRIA LEICESTER course SURREY Expert advice from engineering to DUNDEE medicine, the arts and more… SWANSEA ESSEX AND HUNDREDS MORE... Plus • The Oxbridge interview and the questions they’ll ask • Five ways to make the most of Freshers’ Year • Earn while you learn with Degree Apprenticeships • Stand out from the crowd with your personal statement • Eton College on fast-tracking your route to the top LONDON IS OUR CAMPUS. AND IT CAN BE YOURS TOO. Situated in the heart of London, the University of Westminster is a vibrant, forward-thinking place to study. Home to more than 18,000 students from over 150 countries, our global student network and career-orientated courses can provide you with much more than a good degree. COME TO AN OPEN DAY TO FIND OUT MORE. TO BOOK YOUR PLACE VISIT westminster.ac.uk/open-day-info #WEAREWESTMINSTER XXXXX THE GOOD UNIVERSITIES GUIDE Published by The Chelsea Magazine Company Ltd, Jubilee House, 2 Jubilee Place, London SW3 3TQ Tel (020) 7349 3700 Fax (020) 7349 3701 Email [email protected] -

Part Three – Action Plan 2014 – 2019

Part Three ACTION PLAN Landscape Quality and Character 97 Heather Moorland and Rolling Ridges 99 Limestone Grassland, Cliffs and Screes 101 Broadleaved Woodland and Veteran Trees 102 River Valleys 103 Historic Settlement and Archaeology 104 Industrial Features and the World Heritage Site 105 Hillforts and Defensive Structures 107 Small Historic Features 108 Boundaries 109 Iconic Visitor and Cultural Attractions 110 The Offa’s Dyke National Trail and Promoted Routes 112 The Built Environment 113 People and Communities 114 Landscape Quality and Character Objectives Policy Ref Actions Lead Partners Timescale Support Cadwyn Clwyd Renewable Energy Pilot projects and other appropriate community based projects which seek to mitigate the impact of Cadwyn / Landowners climate change and reduce the carbon footprint Yr 1 Ensure that the natural resources of the AONB without harming the special qualities AONB NRW LQCO1 and special qualities of the AONB PolSQ1 and features of the area or its character and are recognised and valued appearance. Support the Natural Response to Flood Risk project Cadwyn / Landowners in the Clwyd Catchment particularly in relation to Yr1, Yr2 management works within the Clwydian Range AONB NRW Engage with the National Grid’s Visual Impact Provision (VIP) programme to reduce the impact of high voltage transmission in the AONB and its Yr2 setting. Ensure that the impacts of PolSQ1 environmental change on the LQCO2 AONB are understood and a PolSQ2 Promote mast sharing to reduce clutter and impact AONB strategic response is developed on the local landscape character of the AONB. Yr3 and implemented PolSQ3 Work with the industry to apply the seven ‘Holford Rules’ and develop guidance for mitigation Annual measures. -

Henry Hughes, UKERNA

A Study of Networked Video Facilities in Welsh HEIs and FECs and Proposals for a Welsh Video Network DECEMBER 1999 Editor: Henry Hughes, UKERNA Reference: RT/VIDEO/WELSHVC/001 Welsh Video Study Extracts from this document may be reproduced for non-commercial education or training purposes on condition that the source is appropriately acknowledged and the copyright preserved. © FEFCW and HEFCW 1999 Welsh Video Study Contents Page 0 Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 6 2 Technical Background Notes on the Academic Network and Network Video 8 3 Review of Network Provision, Current Facilities and Usage 10 4 The Proposed Video Network 16 5 Services other than Videoconferencing 21 6 Recommendations 22 7 Indicative Costs 23 8 References 26 Appendix 1: Technical Study Team Membership 27 Appendix 2: Network Aspects of Video Provision 28 Appendix 3: Videoconferencing Technology 30 Appendix 4: Usage Questionnaire and Site Survey Form 33 Appendix 5: Instutions’ Geographic Location and Interconnection 44 Appendix 6: FE Network Traffic Statistics 46 Appendix 7: Technical Options Considered 47 Appendix 8: Room Environment 49 Appendix 9: Support for Bilingual Audio 53 Glossary 54 Welsh Video Study Welsh Video Study 0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Objectives and Terms of Reference 0.1 This study was commissioned by the Welsh Funding Councils (WFCs) to provide technically satisfactory and costed proposals for establishing and equipping a good quality, value for money video network encompassing all Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and Further Education Colleges -

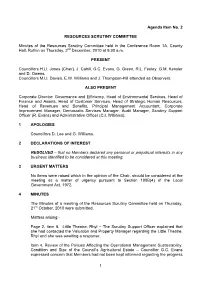

1 Agenda Item No. 2 RESOURCES SCRUTINY COMMITTEE

Agenda Item No. 2 RESOURCES SCRUTINY COMMITTEE Minutes of the Resources Scrutiny Committee held in the Conference Room 1A, County Hall, Ruthin on Thursday, 2nd December, 2010 at 9.30 a.m. PRESENT Councillors H.Ll. Jones (Chair), J. Cahill, G.C. Evans, G. Green, R.L. Feeley, G.M. Kensler and D. Owens. Councillors M.Ll. Davies, E.W. Williams and J. Thompson-Hill attended as Observers. ALSO PRESENT Corporate Director: Governance and Efficiency, Head of Environmental Services, Head of Finance and Assets, Head of Customer Services, Head of Strategic Human Resources, Head of Revenues and Benefits, Principal Management Accountant, Corporate Improvement Manager, Democratic Services Manager, Audit Manager, Scrutiny Support Officer (R. Evans) and Administrative Officer (C.I. Williams). 1 APOLOGIES Councillors D. Lee and G. Williams. 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST RESOLVED – that no Members declared any personal or prejudicial interests in any business identified to be considered at this meeting. 3 URGENT MATTERS No items were raised which in the opinion of the Chair, should be considered at the meeting as a matter of urgency pursuant to Section 100B(4) of the Local Government Act, 1972. 4 MINUTES The Minutes of a meeting of the Resources Scrutiny Committee held on Thursday, 21st October, 2010 were submitted. Matters arising:- Page 2. item 8. Little Theatre, Rhyl – The Scrutiny Support Officer explained that she had contacted the Valuation and Property Manager regarding the Little Theatre, Rhyl and she was awaiting a response. Item 4, Review of the Policies Affecting the Operational Management Sustainability, Condition and Size of the Council’s Agricultural Estate – Councillor G.C. -

The Future of Our Recorded Past

A Report Commissioned by the Library and Information Services Council (Wales) The Future of Our Recorded Past A Survey of Library and Archive Collections In Welsh Repositories By Jane Henderson of Collections Care Consultancy March 2000 Table of Contents Page No… Table of Contents.............................................................................................................. ii The Future of Our Recorded Past - a Summary............................................................... iii Preface........................................................................................................................ ...... vi 1 The Project Brief ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The LISC (Wales) Conservation and Preservation Group.......................................... 1 1.2 A Survey of the Preservation Status of Library and Archive Collections .................. 1 1.3 The Survey Method.................................................................................................... 2 2 Background................................................................................................................... .. 3 2.1 What is Preservation?.................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Why Preservation?...................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Do we Need to Preserve Everything? ........................................................................ -

Explanatory Memorandum to The

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM AND REGULATORY IMPACT ASSESSMENT TO THE ASSEMBLY LEARNING GRANTS AND LOANS (HIGHER EDUCATION) (WALES) (No 2) REGULATIONS 2008. The Explanatory Memorandum has been prepared by the Funding and Student Finance Division of the Department for Children, Education, Lifelong Learning and Skills and is laid before the National Assembly for Wales under Standing Order 24.1. Description 1. These Regulations are required to amend the existing Assembly Learning Grants and Loans (Higher Education) (Wales) Regulations 2008 (No.1273 (W.130)), which came into force on 30 May 2008 as well as the subsequent amending legislation (SI 2008/2140 (W.189)) which came into force on 29 August 2008. These main student support regulations are made on an annual basis to underpin the higher education student support system in Wales. Matters of special interest to the Subordinate Legislation Committee 2. The Committee considered The Assembly Learning Grants and Loans (Higher Education) (Wales) (Amendment) Regulations 2008 on 29 September 2008 (SI 2008/2140 (W.189)). They drew attention to the fact that paragraph 7(1)(b) of Schedule 6 to those amendment regulations contained a cross- reference to paragraph 7 of that Schedule, which should have been to paragraph 6. The context made the intention clear, but the recommendation was that it should be corrected when the principal Regulations are next amended or consolidated. This has been done in these Regulations. In its twenty-eighth report of session 2007-2008 (published 24 October 2008), the Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments (JCSI) reported the equivalent English regulations (The Education (Student Support) (Amendment) (No2) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/1582 as amended)) for defective drafting. -

Cyngor Cymuned Llanfair Dyffryn Clwyd Community Council

CYNGOR CYMUNED LLANFAIR DYFFRYN CLWYD COMMUNITY COUNCIL www.llanfaircommunitycouncil.co.uk Minutes of an Ordinary Meeting of the Council held at Ysgol Pentrecelyn on Monday 14 October 2019 at 7.00 pm. PRESENT – Councillors Jayne Mayers [Chair], David Baker, Bob Barton, Wini Davies [part of the meeting], Owen Evans, Osian Owen, Ceri Ranson [part of the meeting] and Eirwen Godden, Clerk. The Chair welcomed Councillor Owen Evans to his first Council meeting. The Declaration of Acceptance of Office form was duly signed. IN ATTENDANCE - 2 members of the public, Leader of Denbighshire County Council [DCC] Councillor Hugh H Evans Evans OBE and Mr Ben Wilcox-Jones, Senior Engineer DCC. APOLOGIES Councillors Tim Faire & Keith Moulsdale [Vice-Chair] [on holiday] PART 1 596 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Councillor David Baker [Llanfair Church] 597 MINUTES - RESOLVED The minutes of the Meeting held on 9 September 2019 were approved and signed as a correct record. 598 CLERK’S REPORT 598.1 Update on Council Vacancy [565.1, 574.1, 588.1] Reported that the County Council had not received a request for an election following the resignation of Paul Weston and that the Community Council was therefore free to co-opt to fill the vacancy. The Clerk confirmed that notices had been placed on notice-boards and the Council website with a deadline of 25/10/19 for expressions of interest in the vacancy. 598.2 Coleg Cambria Llysfasi College The Clerk stated that, due to annual leave, she had yet to contact Llysfasi College for a meeting to discuss the proposal and, if possible, at a Community Council meeting using the College as a venue on 25/11/19. -

North East Wales

Review of Higher Education Provision in North East Wales Advice to the Minister for Education and Skills June 2013 Digital ISBN 978 1 4734 0312 3 © Crown copyright 2013 WG19858 Review of Higher Education Provision in North East Wales Contents Foreword 1 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Context 13 3. Our Approach 16 4. Profile of North East Wales 18 5. What North East Wales Needs 59 6. How Does Current Provision in North East Wales Measure Up? 83 7. Important Considerations 105 8. Options and Recommendations 109 Annex A: Details of Review Panel Members 126 Annex B: Stakeholder Engagement List 127 Annex C: Additional Evidence List 130 Annex D: Universities and Further Education Colleges Location Map 137 Annex E: Additional Profile Data – North East Wales 138 Review of Higher Education Provision in North East Wales Foreword In February 2012 we were asked by former Minister, Leighton Andrews, to review the provision of higher education in North East Wales. This is the final report arising from the review. In the course of our work we have spoken with more than 160 stakeholders and examined over one hundred items of other evidence. The Review Panel members1 have, without exception, brought dedication and an analytical and independent approach to the task in hand. We in turn have much appreciated the respect shown to our independence; we have not been under pressure to recommend any particular solution. Our conclusions are unanimous. Our vision is one of substantial ambition for higher education in North East Wales and for what it can do for the region into the future. -

Our Plan for Further Education Defined, Career and Skills Focused, Collaborative

Our plan for further education Defined, career and skills focused, collaborative April 2020 Making Education Relevant www.edge.co.uk 1 Our plan for further education Contents Foreword 3 Chapter 1 – Mapping the further education Sector 5 Breadth of FE provision and student population 5 The purpose(s) of colleges 8 The role of FE in promoting social mobility 9 Funding reforms 15 Challenges facing the FE sector in England 18 FE workforce recruitment and retention crisis Increased class sizes and reduced learning hours Low levels of student attainment The marketisation of FE Impact of college mergers Chapter 2 – Views from researchers, FE providers, and policy makers 22 Perspectives from across the UK 24 Chapter 3 – Case studies: 29 Promising practice within the FE sector Chapter 4 – Recommendations and conclusions 41 What Next? A view from the Independent Commission on the College of the Future 44 Notes 45 References 46 Acknowledgements 47 Written by: Dana Dabbous, Riya Patel and Chris Percy Edited by: Olly Newton, Andrea Laczik, Katherine Emms. Reference as: Dabbous, D., Patel,R., Percy,C. (2020). Our Plan for Further Education. Edited by: Newton, O., Laczik, A., and Emms, K. London: The Edge Foundation. April 2020 2 Our plan for further education – Foreword Foreword Our country has reached a pivotal point for the economy and society. Brexit means that, now more than ever, we must make the very most of developing our home-grown talent. Meanwhile the megatrends of demographics, the environment and the fourth industrial revolution will create seismic change over the coming decades. Our further education and skills system must be a key driver in meeting those challenges. -

Professor Williams' Fight Against Alzheimer's

plu s… Peter Stead Wales 2010: Year Zero Simon Brooks Ethnic cleansing in civic Wales Roger Scully Double coalition land Stevie Upton and Brian Morgan Jury out on Ieuan’s new direction Elin Jones Food strategy for the 21st Century Katie-jo Luxton Profes sor Economic growth’s collateral damage John Osmond Wales’s university revolution Williams’ Jane Redfern Jones Border wars in Wrexham Mererid Hopwood fight against Cynghanedd gives life to Welsh verse Prys Morgan Ancient Britons and London Aborigines Alzheimer ’s www.iwa.org.uk Summer 2 01 0 No. 41 | £10 summer 2 010 Editor: John Osmond Associate Editors: Falling out Geraint Talfan Davies Rhys David over money Administration: Helen Sims-Coomber Two weeks following the May election the new Prime Minister David Cameron Design: visited the National Assembly and declared he wanted his relationship with it to marc @th eundercard.co.uk be based on “mutual respect”. He said he regarded the nations of the UK as a To advertise family which he wanted to keep together. And he added, “I don’t want our family Tel: 029 2066 0820 to fall out over money”. However, unless things change pretty soon, and they show little sign of doing so, Cardiff Bay and Westminster will be doing just that. Institute of Welsh Affairs In the Con-Lib 30-page document The Coalition: our programme for government , 4 Cathedral Road published in May, Wales gets just one specific mention, and it’s not encouraging. It Cardiff CF11 9LJ comes under the heading ‘Political Reform’ and states: “We recognise the concerns Tel: 029 2066 0820 expressed by the Holtham Commission on the system of devolution funding. -

Statement of Accounts 2010-11

STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2010-11 FLINTSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL C O N T E N T S Page Flintshire County Council Explanatory Foreword 1-4 Statement of Accounting Policies 5-14 Statement of Responsibilities for the Statement of Accounts 15 Annual Governance Statement 16-30 Core Single Entity Financial Statements - Movement in Reserves Statement 31 - 32 Comprehensive Income and Expenditure Statement for the Year Ended 31st March 2011 33 Balance Sheet as at 31st March 2011 34-35 Cash Flow Statement for the Year Ended 31st March 2011 36 Notes to the Core Financial Statements 37-86 Supplementary Single Entity Financial Statements - Housing Revenue Account Income and Expenditure Account for the Year Ended 31st 87 March 2011 Movement on the Housing Revenue Account Statement for the Year Ended 88 31st March 2011 Notes to the Housing Revenue Account for the Year Ended 31st March 2011 89-90 Group Statements - Group Accounts 91-93 Clwyd Pension Fund Clwyd Pension Fund Accounts for the Year Ended 31st March 2011 94-116 Flintshire County Council and Clwyd Pension Fund Independent Auditor's Report to the Members of Flintshire County Council 117-118 Page 1 EXPLANATORY FOREWORD The Statement of Accounts 2010/11 provides details of the Council’s financial position for the year ended 31st March 2011. The information presented on pages 31 to 93 is in accordance with the requirements of the 2010/11 Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom (the Code) based on International Financial Reporting Statements (IFRS) issued by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA).