1 Silk Path / 2 Nakagawa-Machi Mountain Path: 1 to 2 Comparison Controversies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reliquaries of Hyrule: a Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time

Press Start The Reliquaries of Hyrule The Reliquaries of Hyrule: A Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time Jared Hansen University of Oregon Abstract This study is a semiotic and iconographic analysis of the sacred architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo, 1998). Through an analysis of the visual elements of the game, the researcher found evidence of visual metaphors that coded three temples as sacred spaces. This coding of the temples is accomplished through the symbolism of progression that matches the design of shrines and cathedrals, drawing on iconography and other symbolism associated with Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sacred architecture. Such indications of sacred spaces highlight the ways in which these virtual environments are designed to symbolize the progression of the player from secular to sacred, much like the player’s progression from zero to hero. By using the architecture and symbolism of the three aforementioned belief systems, Ocarina of Time signifies these temples as reliquaries—that is, sacred places that house reverential items as part of the apotheosis of the player. Keywords Art history; The Legend of Zelda; sacred space; symbolism; temple. Press Start 2021 | Volume 7 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hansen The Reliquaries of Hyrule Introduction The video game experiences that I remember and treasure most are the feelings I have within the virtual environments. -

Shinto Ritual Building Practices

Shinto Ritual Building Practices Philip E. Harding History of Art 681 The Ohio State University Shinto, the native religion of Japan, is a very diverse tradition yet one unified by certain ritual practices. Roughly speaking, Shinto can be divided into “folk Shinto” and “shrine Shinto,” but even within these divisions can be found considerable diversity. Every village has its own local traditions that operate independently from, yet related to the shrine tradition. (The folk activities take place on land owned by the shrine.) Within the shrine system there is also diversity, and today we can readily identify at least eighteen separate cults, each with its own style of shrine building1. Within Japan’s own official histories the shrine tradition, particularly the Imperial shrine tradition, has been given the most attention. This tradition experienced continental influences from China and was the one with which the Japanese upper class identified itself. Japan’s folk traditions, practiced in the locale where they first evolved, have largely gone without reference in Japan’s history of art and architecture. Both traditions, however, embrace many related themes and practices. One can find formal dualities expressed in the design of the folk forms and layouts of shrine buildings, as well as some shared motifs such as a “heart pillar.” Most significantly, both traditions periodically build and re-build sacred structures so that the particular built forms are simultaneously ephemeral and enduring – sharing in a kind of temporal immortality. These periodic rebuilding practices serve to reinforce cultural memory and place individuals into the larger stream of sacred time which transcends the temporal, constantly changing world of mortal time. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Department of Architecture

建築学セミナー Introduction to Architecture [Instructor] Hiroki Suzuki, Tatsuya Hayashi [Credits] 2 [Semester] 1st year Spring-Fall-Wed 1 [Course code] T1N001001 [Room] Respective laboratories *Please check the bulletin board of Department of Architecture , that will noticed where the lecture is held [Course objectives] Students and faculty members think together about study methods and attitudes as well as how to be aware of and interested in issues in the Department of Architecture. In particular, this course aims to teach the basic understanding of the fields of urban environmental and architectural planning as well as building structure design and to facilitate forming the basis of communication between the students and faculty members, by exposing the students in class in seminar format to educational research contents in each educational research field of the Department of Architecture. [Plans and Contents] Groups of about 10 students each will be formed. Each group will take a class in seminar format covering a total of four educational research fields and spend three to four weeks per field. The three to four week-long seminar for each field will be planned according to the characteristics of educational research in each field. [Textbooks and Reference Books] Not particularly [Evaluation] The grade will be determined by the average score ( if absent or not turned in) of exercises to be occasionally given during the lecture hours. Students will not be graded if they do not meet the rule of the Faculty of Engineering on the number of attendance days. [Remarks] Students will be assigned to their group in the first week. -

Turystyka Kulturowa. Czasopismo Naukowe

ISSN 1689-4642 Spis treści Artykuły ............................................................................................................. 7 Joanna Kowalczyk-Anioł, Ali Afshar Gentryfikacja turystyczna jako narzędzie rozwoju miasta. Przykład Meszhed w Iranie ....... 7 Rafał G. Nowicki Partycypacja turystów i mieszkańców miejscowości turystycznych w procesie ochrony zabytków architektury....................................................................................................... 26 Andrzej Moniak, Michał Suszczewicz Przestrzeń kulturowa i niechciane dziedzictwo garnizonów poradzieckich na pograniczu Polski i Niemiec ............................................................................................................... 40 Petr Bujok, Martin Klempa, Dominik Niemiec, Jakub Ryba, Michal Porzer Dziedzictwo przemysłowe firmy „Baťa” w mieście Zlín (Republika Czeska) ................... 54 Małgorzata Gałązka, Monika Gałązka Shintō jako walor turystyczny ........................................................................................... 67 Joanna Roszak, Grzegorz Godlewski Chronotop Lubelszczyzny. Ocena atrakcyjności regionu dla turystyki literackiej z wykorzystaniem bonitacji punktowej ............................................................................. 85 Nikoloz Kavelashvili Protecting the Past for Today: Development of Georgia’s Heritage Tourism ..................... 97 Recenzja ......................................................................................................... 110 Czajkowski Szymon -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

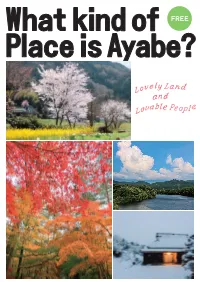

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai. Author: (Katsushika Hokusai) Original Title: (Kanagawa-oki nami ura) Year: 1829 – 1832 Base/stand: Colour-engraved upon a wooden block. Japanese ukiyo-e master. The Great Wave is the most recognized piece by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai, who specializes in ukiyo-e. Published between 1830 and 1833 during the Edo period, it forms part of the collection “Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji”, even though Mount Fuji is the smallest element. The wave references the relentless force of nature, the sea, and the importance this event has in Japan’s economy and its cultural development, given the country is formed by 4 islands. EQUO JUMPTEAM----------FNL-0002RR--_03B 1 Report Created SAT 7 AUG 2021 16 :45 Page 1/7 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Fence 4 – Mascot of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Japanese illustrator Ryo Taniguchi. Manga and gamer references are seen, in representation of the Japanese contemporary visual culture and with a character design inspired by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games’ Logo. The pair of futuristic characters combine tradition and innovation. The name of the Olympics mascot, Miraitowa, fuses the Japanese words for future and eternity. Someity, the Paralympics mascot, is derived from Somei-yoshino, a type of cherry blossom, cherry blossom variety "Someiyoshino" and is a play on words with the English phrase “So mighty”. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

A Bi Oad a Bi Road

#DKMQ#6QYP9JGTG6CNGU#TG$QTP#DKMQ#6QYP9JGTG6CNGU#TG$QTPD U#TG$QTP AA BIB I R OADOAD Shall we take a trip down journey lane? A Town Where YouTube video Website By smartphone By tablet Tales Are Born The pictures come alive! ABIKO Abiko Guidebook Symbol indicating This Is What the Town of Abiko is All About spots with free Wi-Fi. An open park that allows everyone to enjoy the great natural environment near Lake Teganuma. Visitors can relax for the entire day, experience miniature trains, rent boats, and take part in many other activities. 2 26-4 Wakamatsu, Abiko City Shirakaba Literary Sugimura Sojinkan Historic Site of Entry fee: Free Taste of Culture Museum 4 Memorial House and Museum 6 the Kano Jigoro Villa 8 Teganuma Park By foot 10 minutes from Abiko Station (750 m) A Town of Waterfronts Former Murakawa Villa 9 and Birds 10 Mizu no Yakata 12 Museum of Birds 14 The Waterfront Town of Rich Water and Spend a Weekend Fusa: History of the Former Inoue Family Greenery 16 Like in a Resort 18 Development of New Fields 20 Residence 22 A Trip through Eternity Gatherings in Abiko Abiko Souvenirs Abiko Guideposts 24 28 30 32 This is a park full of waterfronts and greenery that runs along Lake Teganuma, which is a symbol of Abiko City. You can view waterfowl right up close, and since benches Visitors are encouraged to use the discounted entry ticket for three museums have been installed you can spend a relaxing time gazing or passport for two museums. -

Transcreation: Intersections of Culture and Commerce in Japanese Translation and Localization

TRANSCREATION: INTERSECTIONS OF CULTURE AND COMMERCE IN JAPANESE TRANSLATION AND LOCALIZATION by Dylan Reilly B.A. in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, College of William and Mary, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Dylan Reilly It was defended on April 8, 2016 and approved by Carol M. Bové, PhD, Senior Lecturer Hiroshi Nara, PhD, Department Chair Thesis Director: Charles Exley, PhD, Assistant Professor ii Copyright © by Dylan Reilly 2016 iii TRANSCREATION: INTERSECTIONS OF CULTURE AND COMMERCE IN JAPANESE TRANSLATION AND LOCALIZATION Dylan Reilly, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This study looks at text-heavy examples of translated Japanese popular media, such as recent video games and manga (Japanese comics) to explore the recent evolution of Japanese-English translation and localization methods. While acknowledging localization’s existence as a facet of the larger concept of translation itself, the work examines “translation” and “localization” as if they were two ends of a spectrum; through this contrast, the unique techniques and goals of each method as seen in translated media can be more effectively highlighted. After establishing these working definitions, they can then be applied as a rubric to media examples to determine which “translative” or “localizing” techniques were employed in the