Keeping It Reel?: a Mixed Methods Content Analysis of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nerds! Cultural Practices and Community-Making in a Subcultural

Nerds!: Cultural Practices and Community-Making in a Subcultural Scene by Benjamin Michael WOO Chun How M.A. (Communication), Simon Fraser University, 2006 B.A. (Hons.), Queen’s University, 2004 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Benjamin Woo 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Benjamin Woo Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: Nerds!: Cultural Practices and Community-Making in a Subcultural Scene Examining Committee: Chair: Richard Smith, Professor Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Stuart Poyntz Supervisor Assistant Professor Cindy Patton Internal/External Examiner Canada Research Chair in Community, Culture & Health Department of Sociology and Anthropology Bart Beaty External Examiner Professor Department of English University of Calgary Date Defended/Approved: August 13, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. -

Curtis Armstrong, King of the Nerds, Comes to Comic Con

Curtis Armstrong, King of the Nerds, Comes to Comic Con Friday, November 10 marks the start of the “Biggest show in the smallest state!” as fans gather at the Rhode Island Convention Center & Dunkin Donuts Center for a weekend of indulgence. In plain language, a bunch of NERDS are taking over Providence. This year, it’s more true than ever because Rhode Island Comic Con will host the largest reunion for the cast of the 1984 American film Revenge of the Nerds. I was granted the opportunity to speak to Revenge of the Nerds‘ Curtis Armstrong, the actor and self- proclaimed “Nerd Founding Father,” about his book Revenge of the Nerd, Rhode Island Comic Con and Providence. Jax Adele: How did this book came about? Curtis Armstrong: The book came about just because for years I’ve been thinking about the different things I have done in my professional career, which goes back 40 years now or more. When actors get together just as a group, we’re always telling stories. And everyone’s got good stories about various points in their career. I had memories that were still pretty fresh, and in addition to that, I just don’t throw away things. So I had journals, diaries, letters and documents, and all sorts of things in a big trunk that got carried around with me for decades. And I was just going through the trunk and I just thought, “Gosh, there’s so much stuff here and it’s so specific.” I figured as a nerd, which I always consider myself to be, even before that word was actually used to define us, the idea of writing the nerd narrative, the nerd’s progress, born a nerd, raised a nerd, that has always been a part of who I am … I just thought it would be handy. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Nerd/Geek Masculinity: Technocracy, Rationality

NERD/GEEK MASCULINITY: TECHNOCRACY, RATIONALITY, AND GENDER IN NERD CULTURE’S COUNTERMASCULINE HEGEMONY A Dissertation by ELEANOR AMARANTH LOCKHART Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Kristan Poirot Committee Members, Tasha Dubriwny Jennifer Mercieca Claire Katz Head of Department, J. Kevin Barge August 2015 Major Subject: Communication Copyright 2015 Eleanor Amaranth Lockhart ABSTRACT Nerd and geek culture have become subjects of increasing public concern in recent years, with growing visibility and power for technical professions and increasing relevance of video games, science fiction, and fantasy in popular culture. As a subculture, nerd/geek culture tends to be described in terms of the experiences of men and boys who are unpopular because of their niche interests or lack of social skills. This dissertation proposes the concept of nerd/geek masculinity to understand discourses of hegemonic masculinity in nerd/geek culture. Examining three case studies, the novel Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card, the neoreactionary political ideology, and the #GamerGate controversy, the dissertation suggests that nerd/geek masculinity responds to a perceived emasculation of men who identify as nerds or geeks by constructing the interests, skills, and behaviors of nerd/geek culture as inherently male traits. In this way, nerd/geek masculinity turns the very traits nerds and geeks are often mocked for into evidence of manhood – as the cost of excluding women and queer people from nerd and geek culture. ii DEDICATION To my friends and family who have supported me through this process of scholarship and survival, especially Aeva Palecek and Emily O’Leary… you are my dearest friends. -

Chanticleer | March 14, 1996

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 1996-03-14 Chanticleer | March 14, 1996 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | March 14, 1996" (1996). Chanticleer. 1171. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1171 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Casino Night Yields Funds for JSU Signs by Amy Ponder *SGA Elections are today 9:00 Chanticleer News Wder a.m. - 4:00 p.m. on the fourth The Student Government Association floor of the TMB. Bring your stu- transformed Leone Cole Auditorium into dent ID card to vote. the old west last Wednesday night for the third annual Casino Night. Profits, totaling over $1700, from this year's Casino Night will help build brick I Voter Registration and marble signs along the main highways "Empower yourself," says the bright entering Jacksonville according to Angel green flyers posted all of over campus Narvaez, SGA 2nd Vice President. "Like this week in announcement of the the ones you see when you come into a Student Rights Party's voter registration major university town," says Nabaez, "like drive. The week-long drive is an attempt Tuscaloosa or Auburn." by the Party to get JSU students to regis- The SGA chose to use the profits to help ter to vote in Jacksonville, says Party build the signs because "it's a little embar- organizer, Scott Harnmond. -

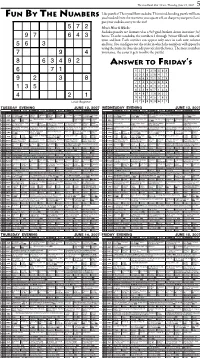

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, June 12, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING JUNE 12, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING JUNE 13, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone CSI: Miami: Under Suspi- Dog Bnty Dog Bounty Mindfreak Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel CSI: Miami: Under Suspi- CSI: Miami: Nailed The Sopranos: The Army (:15) To Be Announced Programming information CSI: Miami: Nailed 36 47 A&E cion (TV14) (HD) (TVPG) (R) (TVPG) (TVPG) (R) (R) cion (TV14) (HD) 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) of One (HD) unavailable. (TV14) (HD) F. Cars (N) NBA (Live) NBA Finals Game 3 (Live) (HD) KAKE News (:05) Nightline J. -

(Don't) Wear Glasses: the Performativity of Smart Girls On

GIRLS WHO (DON'T) WEAR GLASSES: THE PERFORMATIVITY OF SMART GIRLS ON TEEN TELEVISION Sandra B. Conaway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Julie Edmister Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie Katherine Bradshaw © 2007 Sandra Conaway All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor This dissertation takes a feminist view of t television programs featuring smart girls, and considers the “wave” of feminism popular at the time of each program. Judith Butler’s concept from Gender Trouble of “gender as a performance,” which says that normative behavior for a given gender is reinforced by culture, helps to explain how girls learn to behave according to our culture’s rules for appropriate girlhood. Television reinforces for intellectual girls that they must perform their gender appropriately, or suffer the consequences of being invisible and unpopular, and that they will win rewards for performing in more traditionally feminine ways. 1990-2006 featured a large number of hour-long television dramas and dramedies starring teenage characters, and aimed at a young audience, including Beverly Hills, 90210, My So-Called Life, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Freaks and Geeks, and Gilmore Girls. In most teen shows there is a designated smart girl who is not afraid to demonstrate her interest in math or science, or writing or reading. In lieu of ethnic or racial minority characters, she is often the “other” of the group because of her less conventionally attractive appearance, her interest in school, her strong sense of right and wrong, and her lack of experience with boys. -

JEFF KANEW – Editing Credits______

JEFF KANEW – Editing credits____________________ ORDINARY PEOPLE Academy Award Winner for Best Picture Director: Robert Redford Producer: Ronald L. Schwary Paramount Pictures NATURAL ENEMIES Hal Holbrook, Louise Fletcher Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: John Quill Cinema 5 EDDIE MACON’S RUN Kirk Douglas, John Schneider Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: Martin Bregman Universal Pictures BABIJ JAR Katrin Sass, Axel Milberg, Barbara DeRossi Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: Artur Brauner CCC Films Berlin and Montreal Film Festivals ADAM AND EVE Cameron Douglas, Emmanuelle Chriqui Director: Jeff Kanew Producers: Martin Caan, Jeff Kanew National Lampoon NADINE IN DATELAND Janeane Garafolo Director: Amie Stier Producer: Kristen Vadas/Oxygen THE LEGEND OF AWESOMEST MAXIMUS Will Sasso. Kristanna Loken, Rip Torn Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: National Lampoon 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] UNCREDITED FEATURES: (directed films and re-edited after first assembly by credited editors): REVENGE OF THE NERDS (20 TH FOX), GOTCHA (UNIVERSAL), TOUGH GUYS (TOUCHSTONE), TROOP BEVERLY HILLS (WEINTRAUB ENT.), V.I. WARSHAWSKI (HOLLYWOOD) DOCUMENTARY FEATURES: BLACK RODEO Muhammad Ali, Woody Strode Producer/Director: Jeff Kanew YIPPEE Paul Mazursky Producer/Director: Paul Mazursky CANNES WITHOUT A PLAN Director: Julie Robb Producers: Julie Robb, Jodie Fisher, BEFORE I FORGET Kirk Douglas’ One Man Show Director: Jeff Kanew Producers: Kirk and Anne Aouglas SHORT FILMS: GOODNIGHT VAGINA Producer/Director: Stacy Sherman HOPELESSLY DEVOTED Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: Jill Mazursky JESUS SEX SCANDAL Producer/Director: Jeff Kanew Funny Or Die CURSED (Web Series Pilot) Director: Jeff Kanew Producer: Yuri Brown CREATED AND EDITED TRAILERS for over 500 films, including THE GRADUATE, MIDNIGHT COWBOY, THE LION IN WINTER, SHAMPOO, ANNIE HALL, BANANAS,YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN, ALL THE PRESIDENTS MEN, ROCKY, ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST, THE ROSE, ON GOLDEN POND 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. -

The Prankster

presents in the tradition of REVENGE OF THE NERDS and SIXTEEN CANDLES comes the Prankster A film by Tony Vidal Laughter is the best revenge Ken Davitian Kurt Fuller (Borat, Get Smart) (The Pursuit of Happyness) Maiara Walsh Robert Adamson (Mean Girls 2, Desperate Housewives) (It's Complicated, It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia) Madison Riley Devon Werkheiser (Grown Ups, Fired Up!) (We Were Soldiers, Marmaduke) Jareb Dauplaise (Epic Movie, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen) NEW ON DVD FROM STRAND RELEASING HOME ENTERTAINMENT ON SEPTEMBER 28TH, 2010 SYNOPSIS Chris Karas is the brilliant leader of The Pranksters, a secret society that rights the wrongs of high school by pulling sophisticated pranks on deserving oppressors. But with graduation looming, Chris longs for more from life. Guided by the homespun wisdom of his charmingly eccentric Uncle Nick, Chris embarks on a challenging path of self-discovery and romance. Hilarious, heartfelt, and magical, The Prankster is an exciting new high school comedy, destined to be the next teen classic. the Prankster Street date: September 28th, 2010 Pre-book: August 31st, 2010 Catalog Number: 3002-2 UPC Number: 7 12267 30022 8 Suggested Retail Price: $24.99 Stats: 117 minutes - Color - Widescreen - Not Rated – Closed Captioned DVD Bonus Features: • Director's Commentary • Bloopers • Deleted Scenes • The Making of The Prankster • Original Theatrical Trailer • Trailers from Other Films by Strand Releasing For photos/press kits, please visit www.strandreleasing.com, enter our pressroom and download. Press Contacts and screener requests: Marcus Hu Chantal Chauzy [email protected] [email protected] Samantha Klinger [email protected] Phone: 310-836-7500 CAST MATT ANGEL Matt Angel is certainly a rising young star. -

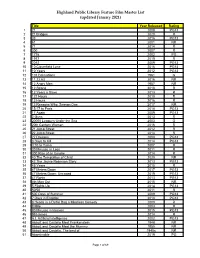

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (Updated January 2021)

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (updated January 2021) Title Year Released Rating 1 21 2008 PG13 2 21 Bridges 2020 R 3 33 2016 PG13 4 61 2001 NR 5 71 2014 R 6 300 2007 R 7 1776 2002 PG 8 1917 2019 R 9 2012 2009 PG13 10 10 Cloverfield Lane 2016 PG13 11 10 Years 2012 PG13 12 101 Dalmatians 1961 G 13 11.22.63 2016 NR 14 12 Angry Men 1957 NR 15 12 Strong 2018 R 16 12 Years a Slave 2013 R 17 127 Hours 2010 R 18 13 Hours 2016 R 19 13 Reasons Why: Season One 2017 NR 20 15:17 to Paris 2018 PG13 21 17 Again 2009 PG13 22 2 Guns 2013 R 23 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 2003 G 24 20th Century Women 2016 R 25 21 Jump Street 2012 R 26 22 Jump Street 2014 R 27 27 Dresses 2008 PG13 28 3 Days to Kill 2014 PG13 29 3:10 to Yuma 2007 R 30 30 Minutes or Less 2011 R 31 300 Rise of an Empire 2014 R 32 40 The Temptation of Christ 2020 NR 33 42 The Jackie Robinson Story 2013 PG13 34 45 Years 2015 R 35 47 Meters Down 2017 PG13 36 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 2019 PG13 37 47 Ronin 2013 PG13 38 4th Man Out 2015 NR 39 5 Flights Up 2014 PG13 40 50/50 2011 R 41 500 Days of Summer 2009 PG13 42 7 Days in Entebbe 2018 PG13 43 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag a Mindless Comedy 2000 R 44 8 Mile 2003 R 45 90 Minutes in Heaven 2015 PG13 46 99 Homes 2014 R 47 A.I. -

Proquest Dissertations

BIG MEN ON CAMPUS: SELLING THE FRAT-HOUSE COMEDY by Thomas A. Larder, B.A. (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario (September 24, 2009) Copyright © 2009, Thomas A. Larder Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-58452-1 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-58452-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2009 Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age Jason Tocci University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Other Communication Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Tocci, Jason, "Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age" (2009). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 953. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/953 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/953 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geek Cultures: Media and Identity in the Digital Age Abstract This study explores the cultural and technological developments behind the transition of labels like 'geek' and 'nerd' from schoolyard insults to sincere terms identity. Though such terms maintain negative connotations to some extent, recent years have seen a growing understanding that "geek is chic" as computers become essential to daily life and business, retailers hawk nerd apparel, and Hollywood makes billions on sci-fi, hobbits, and superheroes. Geek Cultures identifies the experiences, concepts, and symbols around which people construct this personal and collective identity. This ethnographic study considers geek culture through multiple sites and through multiple methods, including participant observation at conventions and local events promoted as "geeky" or "nerdy"; interviews with fans, gamers, techies, and self-proclaimed outcasts; textual analysis of products produced by and for geeks; and analysis and interaction online through blogs, forums, and email.