Fine Lees.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riesling Originated in the Rhine Region of Germany

Riesling Originated in the Rhine region of Germany 1st mention of it was in 1435 when a noble of Katzenelbogen in Rüsselsheim listed it at 22 schillings for Riesling cuttings Riesling comes from the word “Reisen” means “fall” in German…grapes tend to fall off vines during difficult weather at bud time Riesling does very well in well drained soils with an abundance of light, it likes the cool nights. It ripens late so cool nights are essential for retaining balance Momma and papa Parentage: DNA analysis says that • An aromatic grape with high Gouais Blanc was a parent. acidity Uncommon today, but was a popular • Grows in cool regions wine among the peasants during the • Shows Terroir: sense of place middle ages. The other parent could have been a cross of wild vines and Traminer. Riesling flavors and aromas: lychee, honey, apricot, green apples, grapefruit, peach, goose- berry, grass, candle wax, petrol and blooming flowers. Aging Rieslings can age due to the high acidity. Some German Rieslings with higher sugar levels are best for cellaring. Typically they age for 5-15 years, 10-20 years for semi sweet and 10-30 plus years for sweet Rieslings Some Rieslings have aged 100 plus years. Likes and Dislikes: Many Germans prefer the young fruity Rieslings. Other consumers prefer aged They get a petrol note similar to tires, rubber or kerosene. Some see it as fault while others quite enjoy it. It can also be due to high acidity, grapes that are left to hang late into the harvest, lack of water or excessive sun exposure. -

Got Grosses Gewächs?? Taking the Fear out of German Wine Classifications

1/25/2017 Got Grosses Gewächs?? Taking the fear out of German wine classifications Lucia Volk, PhD, CSW Wine Educator, MindfulVine.com SWEbinar January 28, 2017 Brief Introduction: Lucia Volk PhD in Anthropology Wine Educator, MindfulVine.com Professor at San Francisco State University Riesling Promoter 1 1/25/2017 Overview of today’s SWEbinar 1. What is the VDP? 2. Overview of the German Wine Classification System 3. The Search for Distinction 4. Meet some VDP Members 5. Pros and Cons of the VDP Classification System Got Grosses Gewächs?? SWEbinar January 28, 2017 1. What is the VDP? Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter => Association of German Prädikat Wine Estates Incorporated as VDP in 1971 Approx. 200 members, who cultivate 5% of German vineyards and produce approx. 3% of German wine Average vineyard size: 25.5 hectares [60+ acres] Average production: 156,000 bottles [13,000 cases] 2 1/25/2017 1. What is the VDP? Let us all say it: Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter Fir-bant Doy-tsher Pre-dee-kahtz-wine-ghyy-tar 1. What is the VDP? The current Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter emerged from a previous organization founded in the town of Trier on the Mosel in 1910, called the VDNV 3 1/25/2017 1. What is the VDNV?? Verband Deutscher Naturweinversteigerer => Association of German N-Wine Auctioneers And here is how you say it: Fir-bant Doy-tsher Na-tour-wine-fir-stahy-ga-rar 1. What is the VDNV?? Association of German N-Wine Auctioneers - founded 26 November 1910 - 4 regional wine associations [Rheingau, Mosel, Pfalz, Rheinhessen] started to coordinate wine auctions for unchaptalized (“Natur”) wines - Goal: to distinguish between “pure” estate- bottled and “modified” by-the-barrel wines 4 1/25/2017 VDNV Wine Auction, 1926 [VDP archives] German vineyards are among the world’s coldest 50th parallel of latitude continental climate 5 1/25/2017 German vineyards are among the world’s coldest 50th parallel continental climate 1. -

Chemical and Sensory Characterisation of Sweet Wines Obtained by Different Techniques

Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 33(1) 15-30. 2018 CHEMICAL AND SENSORY CHARACTERISATION OF SWEET WINES OBTAINED BY DIFFERENT TECHNIQUES CARACTERIZAÇÃO QUÍMICA E SENSORIAL DE VINHOS DOCES OBTIDOS POR DIFERENTES TÉCNICAS José-Miguel Avizcuri-Inac1,3,4, Marivel González-Hernández1,4, Daniel Rosáenz-Oroz5, Rodrigo Martínez- Ruiz1, Luis Vaquero-Fernández1,2* 1 Department of Chemistry and 2 Laboratory Service. University of La Rioja. Madre de Dios, 53. 26006. Logroño, Spain. 3 Bodegas Ontañón S.L. Machín sn, 26559. Aldeanueva de Ebro, Spain. 4 Institute of Vine and Wine Sciences (UR, CSIC, GR). Finca La Grajera, Autovía del Camino de Santiago LO-20 Salida 13, 26007. Logroño, Spain. 5 Sociedad Cooperativa de Albelda, Escuelas Pías, 20, 26120. Albelda de Iregua, Spain. * Corresponding author: Tel: +34 941299699, e-mail: [email protected] (Received 13.01.2018. Accepted 19.03.2018) SUMMARY Little is known about the chemical and sensory characteristics of natural sweet wines obtained by different grape dehydration processes. The main aim of this work is to characterise several natural sweet wines, in order to understand the influence of grape dehydration on the chemical and sensory profile of those wines. First, conventional oenological parameters and low molecular weight phenolic compounds have been determined. Next, sensory descriptive analysis was performed on individual samples based on citation frequencies for aroma attributes and conventional intensity scores for taste and mouth-feel properties. Low molecular weight phenolic compounds and acidity were found in a lower concentration in most wines from off-vine dried grapes. Late harvest wine presented higher amounts of phenolics. White wines showed higher sensory and chemical acidity. -

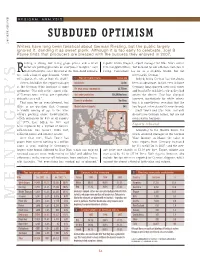

Subdued Optimism

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SUBDUED OPTIMISM 2/08 MEININGER’S WBI 2/08 MEININGER’S Writers have long been fanatical about German Riesling, but the public largely ignored it, deriding it as sweet plonk. Although it is too early to celebrate, Joel B. Payne finds that producers are pleased with the success they enjoyed in 2007. iesling is strong, but rising grape prices and a weak reports Armin Wagner, export manager for Blue Nun’s owner dollar are putting pressure on everyone’s margins,” says F.W. Langguth Erben, “but demand for our off-shore varietals is RMartin Henrichs, sales director at the Moselland coopera- rising. Consumers see us as a credible brand, but not tive, with a hint of apprehension. “2008 necessarily German.” will separate the wheat from the chaff.” 1 Benchmark Data www.de Indeed, being German has not always Steven Schindler, the export manager Inhabitants: 82.2m been an advantage. In fact, even at home at the German Wine Institute is more Germans long spurned their own wines Per head annual consumption: 23.7 litres optimistic. “Not only is the export value and bought French labels when they had of German wine rising, our reputation Area under production: 102,000 hectares guests for dinner. That has changed, abroad is on a roll.” however, particularly for white wines, Domestic production: 1bn litres That may be an overstatement, but but it is nonetheless revealing that the there is no question that Germany Market share of imports: 54% two largest international German brands is slowly coming of age in the wine – Black Tower and Blue Nun - not only world’s pecking order. -

Bullion Cellars and the G4 ... Wines from 4 Different Countries

BULLION 14C www.bullioncellars.com.au Bullion Cellars and the G4 ... Wines from 4 different countries dry, but if I told you the residual sugar is 9.0 g/l this would be shockingly sweet, if I did not mention that the acid is 9.3g/l – balancing it all out. The first red wine is from the Rhone valley and the village of Lirac - 2011 Chateau Mont Redon Lirac. This is the second time a sommelier has chosen this wine but when Kim suggested the 2011 vintage we could not wait to include it in the G4. Lirac is one of the last and best-kept secrets in the Rhone Valley. This Southern Rhone region has for years been over shadowed by the likes of Chateauneuf-du-Pape and Gigondas. Great news for us because Lirac is still ridiculously good value. What also got us excited about this wine is the embossed bottle Mont Redon is now using. This looks just beautiful and is quite expensive to implement, so it shows the faith the winery has in the wine and region. It is a Grenache based wine that is a joy to drink, and looks bloody good too. Australian Shiraz is going through a significant change of late. It is very similar We have not done this for a while. Normally we have a few wines from the to what has happened to Chardonnay. (It is now almost impossible to find a same country, but not this time. Australia, Germany, France and Spain. full bodied, heavily wooded Chardonnay as the modern style is more lean We are calling this our “G4 Wine Selection” in recognition of the G20 and crisp). -

C L E a N, H O N E S T, I R I

A note about our wine programme Wine lists evolve over time to compliment a restaurant’s style and tone, as well as the ever changing taste of the public at large. Our list here in West Restaurant is designed to mirror the restaurant’s dining menu - sophisticated yet accessible, as well as taking inspiration from around the world. As with our menu, we change our wine list monthly to reflect the season. Therefore, even our long-time friends may want to take a close look. For any taste, meal or mood, an array of possibilities awaits. If you would like assistance with your selection or care to have a Fine Vintage Port or Wine decanted prior to your arrival, please speak to Mathieu, Fergal or I or any member of our knowledgeable team. Please use us to help you with a wine recommendation and introduce you to something new. Trust us and try a varietal you have not tasted before. The grape varietal is the DNA of the wine. This is where the fun begins with wine and it is where you will learn the most from your time with us. As one of Ireland’s first restaurants to begin using the Coravin wine preservation system, we are delighted to be able to offer you a glass of any of our premium wines. So you can now taste that bucket list! I hope we have created a wine list that is both enlightening and entertaining. I wish you memorable tasting pleasures. Fergus General Manager / Sommelier Dive into the blue with Canto 5, a Spanish blue wine, exclusive to The Twelve The Twelve, with its usual quirky and intriguing take on all things food and wine, is serving a new wine that drinks like a rosé, but looks like nothing you’ve ever seen. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX A The Exemplary Nature of a Symbiosis Barrier to imitation 46 Acid (in wine and food) 107–111 between Food Dishes and Barsac (wine) 291 acetic 107 Cognacs 150–153 Basics of wine evaluation 23–26 citric 107, 109 The Italian Wine and Food Basque 235 in food 110 Perspective 5–8 Baton Rouge 68 in wine 108 Which to Choose First, Wine or Bayou La Seine 190 lactic 107 Food? 102 Bazzoni, Enrico 5, 8 levels 109, 119, 121, 123, 125 Appellation 55 Beamsville Bench 208 malic 107 Appellation d’Origine Controˆle´e (AOC) Beaujolais 29, 84, 109, 158, 192, 260, tartaric 107 30, 55, 59, 79 298 types Arbois (wine) 191 Beerenauslese wines 292 Acidity 32, 33, 102, 103, 107, 134, 170 Archestratus 6 Bentwood box cookery 235 Adaptation (to sensations) 26 Archetypal ingredients 78 Beurre blanc 224 Affective testing 22 Armagnac 295 Bianco di Custoza 195 Aftertaste 216 Aroma 24, 28 Bias 26 Aging (wine) 159, 272 wheel 24 Biscotti 302 Agri-food systems 46 quality 24 Bitterness 32, 33, 138 Alcohol level 104, 156, 270 Aromatic compounds 24 in cheese 272 Aligote´ (wine) 136 Artichokes 224 in food 133 Alois Lageder, Pinot Bianco 16 Asiago 278 in food and wine pairing Alsace 291 Asparagus 224 in wine 132 Alto Adige 15 Asti Spumate 299 Amarone 278, 292, 297 Astringency 32, 154, 155 how to identify 32 American Culinary Federation (ACF) 68 Attitude 311 Bittersweet Plantation 49, 67 American Viticultural Area (AVA) 55 Auslese 170, 292 Black Muscat 294 Amerine 52 COPYRIGHTEDAutochthonous vines 6 MATERIALBlackening 171 Amontillado 213, 294 Blanc de Blancs 133 Analytical -

GOLD EDITION About Blue Nun Wines

About Blue Nun Wines The history of Blue Nun goes further back in the German winemaking than the history of the Langguth company itself. Nuns have known how to make exquisite wines for centuries. This is where Blue Nun, the leading premium export brand from F. W. Langguth has its roots. With a history going back 400 years, Blue Nun is one of the most important brand name wines outside Germany. GOLD Today, Blue Nun represents wines from the heart of Germany. State-of-the-art cellar technology is the guarantee of consistently high quality. Blue Nun has EDITION achieved real cult status over the last few decades, and is a guarantee of Blue Nun 22K GOLD EDITION is successful trade partnerships. a high quality sparkling wine, with a full, rounded fl avour. Light and bluenunworld.com elegant in style with “magical energy“. What makes it really distinctive Distributed by: F.W. Langguth Erben GmbH & Co.KG is that it contains fi ne pieces of Dr. Ernst-Spies-Allee 2 · 56841 Traben-Trarbach · Germany 22-carat gold leaf, designed to Phone: +49 6541 17275 highlight its natural effervescence. [email protected] · www.langguthworld.com A great apéritif or accompaniment for light meals and hors d’oeuvres, this is the perfect wine for celebra- tions, special occasions, and life’s golden moments. dry sweet Aussenseite Blue Nun wines are RIESLING RIVANER MERLOT PINK ICE EISWEIN unique through BLUE NUN - The Aromatic, fruity and racy - that Blue Nun MERLOT is sourced Blue Nun PINK ICE is a very Blue Nun EISWEIN is the ulti- Riesling Specialist is how connoisseurs love their from the Languedoc region of special quality red wine from mate natural German Ice Wine their unparalleled grapes from the River Rhine. -

A Note About Our Wine Programme

A note about our wine programme Wine lists evolve over time to compliment a restaurant’s style and tone, as well as the ever changing taste of the public at large. Our list here in West Restaurant is designed to mirror the restaurant’s dining menu - sophisticated yet accessible, as well as taking inspiration from around the world. As with our menu, we change our wine list monthly to reflect the season. Therefore, even our long-time friends may want to take a close look. For any taste, meal or mood, an array of possibilities awaits. If you would like assistance with your selection or care to have a Fine Vintage Port or Wine decanted prior to your arrival, please speak to Mathieu, Fergal or I or any member of our knowledgeable team. Please use us to help you with a wine recommendation and introduce you to something new. Trust us and try a varietal you have not tasted before. The grape varietal is the DNA of the wine. This is where the fun begins with wine and it is where you will learn the most from your time with us. As one of Ireland’s first restaurants to begin using the Coravin wine preservation system, we are delighted to be able to offer you a glass of any of our premium wines. So you can now taste that bucket list! I hope we have created a wine list that is both enlightening and entertaining. I wish you memorable tasting pleasures. Fergus General Manager / Sommelier Dive into the blue with Canto 5, a Spanish blue wine, exclusive to The Twelve The Twelve, with its usual quirky and intriguing take on all things food and wine, is serving a new wine that drinks like a rosé, but looks like nothing you’ve ever seen. -

Ohio Brand Listing

OHIO BRAND LISTING WE ARE FAMILY TM southernglazers.com Bourbon/Whiskey Canadian Tequila Early Times Bourbon Ole Smoky Southern Comfort Canadian Club Cocktail Time Mccormick Blend Phillips Union Whiskey Terresentia Classic Mccormick Tequlia Rum/Cachaça Adm Nelson Cocktail Cruzan Flavored Rums Don Q Coco Rum Cal Jack Flaverd Rum Captain Morgan Cruzan Velvet Mccormick Rum Rum Haven Captain Morgan Parrot Bay Don Q Base Prichards’s Cream Sugar Island Gin Vodka McCormick Gin Gran Legacy Mccalls Vodka Pimm’s Cup Kamchatka Mccormick Vodka Popov Vodka Cordials/Liqueurs Alambicco Chambord Liquoer Hpnotiq Mccormick Egg Nog Rum Chata Amarula Cream Copa De Oro Hpnotiq Harmonie Gf St Germain Baileys Caramel Crave Liqueur Ice Hole Mccormick Irish Stirrings Liqueur Baileys Cherry Dekuyper Burst Irishman Cream Tequila Rose Baileys Chocolate Dekuyper Luscious John Dekuyper Mccormick Triple Sec Tippy Cow Baileys Coffee Dekuyper Pucker Joseph Carton Midori Trader Vic Cordials Baileys Espresso Dekuyper Sig Kamora Nuvo Ty Ku Liq Baileys Hazelnut Dorda Chocolate Keke Beach Key Lime Or-G Ty Ku Soju Baileys Irish Cream Liqueur Kerrygold O’sullivans Irish Villa Massa Baileys Vanilla Dubochet Cordials Kinky Pama Pamagranite Whisper Creek Cinnamon Emmet’s Irish Cream Kringle Cream Liqueur Berentzen Evan Williams Season Leroux Cordials Pescevino Brady’s Irish Cream Fratello Leroux Schanps Qream Brown Jug Spirits Gianduia Llords Cordials Rio Grand Triple Sec Cappelletti Godiva Liqueur Mathilde Royal Spirits Spirit Premixes Jack Daniels Winter Montebello Margarita -

FLIGHTS BUBBLES Who Said It BEST 37 "I Drink Champagne When I'm

BUBBLES Who said it BEST 37 "I drink Champagne when I’m happy and when I’m sad. Sometimes I drink it when I’m alone..." -Lily Bollinger Francis Orban Extra Brut, Champagne, France NV Bollinger Special Cuvée, Champagne, France NV Krug Grande Cuvée, Champagne, France MV FLIGHTS WHITES Not Your Grandpa’s Riesling 18 Dry and delicious, with all the fruits, minerals and thankfully no new oak or gobs of sugary sweetness. While Blue Nun had its moment, it is now time to celebrate and enjoy how good dry Riesling can be. Stadt Krems Riesling, Kremstal, Krems, Austria 2019 Ravines Dry Riesling, Finger Lakes, New York 2017 Dr. Bürklin-Wolf Riesling Troken, Pfalz, Germany 1999 Unusual Suspects 17 Ready to try something new? These indigenous white Portuguese grapes have lots of personality driven by minerals, ripe fruits and a kiss of new oak. There is a reason why everyone is moving to Portugal… Textura de Estrela Encruzado/Bical/Cerceal, Dao, Portugal 2018 Muxagat “Os Xistos Altos” Rabigato, Duoro, Portugal 2018 Rovisco Garcia Antão Vaz/Arinto, Alentejano, Portugal 2016 Dual Monarchy 16 Take a journey through the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, this time no war, just some crisp mineral driven wines. Stadt Krems Riesling, Kremstal, Krems, Austria 2019 Barta Furmint, Tokaj Hungary 2015 Edi Simčič Tokata, Goriška Brda, Slovenia 2018 Euro Cup 19 Mr. Big 47 France, Italy and Austria, three heavyweights on the world stage. Will it be Sophisticated, lots of personality and all the charm! Whether he is living the upstart Gruner and its perfectly balanced attack, the Chablis with its in Napa, meeting you in Paris or taking you on a tip to Argentina; your chalky minerality that dominates the finish or the Pinot Grigio that is simply timing (unlike Carrie’s) is perfect to fall in love with Big. -

Copy of Capitol-Husting Product Portfolio 4-4-2019.Xlsx

ABSINTHE Copper & Kings Amerique 1912 Absinthe - Made in Wisconsin Absente Liqueur Grande Absente AMARO / BITTER LIQUEURS Angostura Amaro Meletti 1870 Bitter Antico Amaro Rinomato Americano Killepitsch Rinomato Aperitivo Deciso Lorenzo Inga My Amaro St Raphael Dore Meletti Amaro St Raphael Rouge Nonino Amaro Vincenzi Arancia Martini & Rossi Bitters Vincenzi Capasso Zwack BEER / CIDRE Baltika #3 Classic Baltika Imperial Stout Baltika #6 Porter Keo Greek Beer Baltika #7 Dortmunder Mesh & Bone Pamplemousse Cidre Baltika #8 Hefeweizen Mesh & Bone Pomme et Poire Cidre Baltika #9 Strong Lager BITTERS The Bitter Truth: The Bitter Truth: Bogart's Bitters Peach Bitters Celery Bitters Tonic Bitters Chocolate Bitters Blossom Drops & Dashes Creole Bitters Nut Drops & Dashes Cucumber Bitters Roots Drops & Dashes Grapefruit Bitters Wood Drops & Dashes Jerry Thomas' Own Decanter Bitters Orange Flower Water Lemon Bitters Rose Water Old Time Aromatic Bitters Olive Bitters Copper & Kings: Orange Bitters Old Fashioned Bitters BRANDY – DOMESTIC Copper & Kings Koval "Susan for President" Peach - Organic/Kosher Clear Creek Koval "Susan for President" Prune - Organic/Kosher Crooked Water - Made in Wisconsin Pocket Shot Brandy Gld Artisan Series / Rehorst - Made in Wisconsin Potter`s Brandy Jacquin's BRANDY ‐ IMPORTED/COGNAC Camus VS Cognac Laurendeaux VS Cognac Camus VSOP Cognac Maison Rouge VS Cognac Cardenal Mendoza Brandy Maison Rouge VSOP Cognac Chalfonte VSOP Cognac Massenez Dusee VSOP Cognac Vendome VSOP Brandy Dusee XO Cognac Vendome XO Brandy Hardy