Camelot's Reaction to Sir Gawain's Failure Senior Paper Presented In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Production 2019.Xlsm

CustomEyes® Book List Title Author ISBN RRP Publisher Age Synopsis Mr and Mrs Brick are builders, just like their mothers and fathers and grandmothers and grandfathers. But their new baby doesn’t seem to be following in their footsteps. Instead of building things up, she keeps Happy Families - Miss Brick the Builders' Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312423 £4.99 Puffin 06+ knocking things down! Baby Miss Josie Jump the jockey can’t wait to gallop in a race like her mum, her brother and even her grandma, but everyone says she’s too young. But then grandma’s horse gets a sore throat and Jimmy Jump gets a Happy Families - Miss Jump the Jockey Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312416 £4.99 Puffin 06+ splinter in his bottom Mr Biff is a boxer but he likes to eat cream cakes and sit by the fire in his slippers. Mr Bop is a boxer too, but he’s the fittest, toughest man in town. So Mr Biff needs to train hard before their charity match – but will he Happy Families - Mr Biff the Boxer Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312362 £4.99 Puffin 06+ strong enough to swap his cream cakes for carrots? Mr Buzz works hard to look after his bees - and his bees work hard to make lots and lots of lovely honey. But one morning Mr Buzz sees his bees swarming and he knows that when bees swarm and buzz off together Happy Families - Mr Buzz the Beeman Ahlberg, Allan 9780140312447 £4.99 Puffin 06+ they never come back. So the Buzz family put on their bee hats and bee gloves and give chase. -

Camelot in Spokane.Pub

CAMELOT IN SPOKANE Includes Lake Chelan March 25, 2015 - 5 Days Fares Per Person : $995 double/twin $1250 single $950 triple Tour is exempt from GST. >>>Early Bookers: $60 discount on first 15 seats; $30 on next 10 >>>TIC Travel Insurance: Plan 3-Comprehensive $95 double/twin, $119 single, $90 triple Redeem Experience Points : Book by February 11 and redeem up to 26 e-points Includes • Coach transportation for 5 days • Locally-guided tour of Spokane • 4 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes • Transfer to and from INB Theatre • 4-course wine pairing dinner at Tsillan Cellars • Ticket to Camelot at INB Theatre • Orchard ride at Orondo Cider Works with cider • Knowledgeable tour director sampling and donuts • Luggage handling at hotels • Gourmet dinner at Patsy Clark’s Mansion • 7 meals : 2 breakfasts, 3 lunches, 2 dinners • Wine tasting at Patit Creek Cellars Experience Points: Earn 26 e-points Camelot Show Seating • Orchestra Level Right Centre Rows K to N • A seating plan for INB Center is available at our offices. • Please book early as theatre seats are assigned in the order that you book. Camelot Camelot was composed by Alan Jay Lerner (lyrics) and Frederick Loewe (music) and was based on the King Arthur legend as adapted from the T.H. White novel, The Once and Future King . After their success with My Fair Lady , there were high expectations for Camelot . It opened in Toronto in 1960 with stars Julie Andrews, Robert Goulet and Richard Burton. The running time was supposed to be 2½ hours, but instead it clocked in at 4½ hours and the exhausted audience went home at 1 a.m. -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

Mcsporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction

McSporran, Cathy (2007) Letting the winter in: myth revision and the winter solstice in fantasy fiction. PhD thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5812/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Letting the Winter In: Myth Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction Cathy McSporran Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature, University of Glasgow Submitted October 2007 @ Cathy McSporran 2007 Abstract Letting the Winter In: Myth-Revision and the Winter Solstice in Fantasy Fiction This is a Creative Writing thesis, which incorporates both critical writing and my own novel, Cold City. The thesis explores 'myth-revision' in selected works of Fantasy fiction. Myth- revision is defined as the retelling of traditional legends, folk-tales and other familiar stories in such as way as to change the story's implied ideology. (For example, Angela Carter's 'The Company of Wolves' revises 'Red Riding Hood' into a feminist tale of female sexuality and empowerment.) Myth-revision, the thesis argues, has become a significant trend in Fantasy fiction in the last three decades, and is notable in the works of Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman and Philip Pullman. -

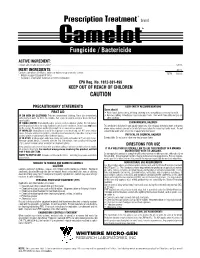

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

The Duke: Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack

™ Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack The politics of the high courts are elegant, shadowy, and subtle. Fort Tile: Players can use the Fort Tile as shown on pages 7-8 of Not so in the outlying duchies. Rival dukes contend for unclaimed the rulebook for any game with these tiles. However, they can also lands far from the king’s reach, and possession is the law in these play with the reverse side of the Fort, Camelot. Camelot is an Ex- lands. Use your forces to adapt to your opponent’s strategies, cap- panded Play tile (see p. 6 of the rulebook) and so both players should turing enemy troops, before you lose your opportunity to seize these agree to its use before play begins. lands for your good. Randomly place Camelot in any square in one of the two middle In The Duke, players move their troops (tiles) around the board rows of the board. and flip them over after each move. Each tile’s side shows a different For the Arthur player, if one of his Arthurian Legends’ tiles is in- movement pattern. If you end your movement in a square occupied side Camelot (King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, or Merlin), by an opponent’s tile, you capture that tile. Capture your opponent’s then the Camelot Tile gains Command ability in all eight squares Duke to win! surrounding Camelot. On his turn, any time those conditions are met, the player may use the Command ability of Camelot; the Troop ARTHurIan leGenDS EXPanSIon PacK RULES Tile on Camelot does not flip, but the Camelot Tile DOES flip over to Arthur, Guineviere, Merlin, Lancelot and Perceval replace the light the Fort side; as long as it’s on the Fort side, the Command ability no stained Duke, Duchess, Wizard, Champion and Assassin Tiles. -

Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart by Chrétien De Troyes

Lancelot, The Knight of the Cart by Chrétien de Troyes Translated by W. W. Comfort For your convenience, this text has been compiled into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart Table of Contents Acknowledgments......................................................................................................................................3 PREPARER'S NOTE: ...............................................................................................................................4 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY: ...............................................................................................................4 The Translation..........................................................................................................................................5 Part I: Vv. 1 - Vv. 1840..........................................................................................................................5 Part II: Vv. 1841 - Vv. 3684................................................................................................................25 Part III: Vv. 3685 - Vv. 5594...............................................................................................................45 Part IV: Vv. 5595 - Vv. 7134...............................................................................................................67 Endnotes...................................................................................................................................................84 -

1 | Page the HISTORIAN England 932 A.D. a Kingdom Divided. to The

1 | P a g e THE HISTORIAN England 932 A.D. A Kingdom divided. To the West- the Anglo Saxons, to the East- the French. Above nothing but Celts and some people from Scotland. In the kingdoms of Wessex, Sussex, and Essex and Kent - Plague. In Mercia and the two Anglias - Plague: with a 50% chance of pestilence and famine coming out of the Northeast at twelve miles per hour. Legend tells of an extraordinary leader, who arose from the chaos, to unite a troubled kingdom. This man was Arthur, King of the Britons! And King Arthur gathered more Knights together, bringing from all the corners of the Kingdom the strongest and bravest in the land to sit at the Round Table. The strangely flatulent Sir Bedevere. The dashingly handsome Sir Galahad. The homicidally brave Sir Lancelot. Sir Robin, the Not-quite-so- brave-as-Sir- Lancelot, who slew the vicious chicken of Bristol and who personally wet himself at the Battle of Badon Hill. Together they formed a band whose deeds were to be retold throughout the Centuries, The Knights of the Round Table! KING ARTHUR Hail good sir. I am Arthur, King of the Britons, Lord and Ruler of all of England, and Scotland. And even tiny little bits of Gaul. We have ridden the length and breadth of the land in search of knights to join me in my court at Camelot. I must speak with your lord and master. (listens) ... He’s busy? Good Sir, we have ridden since the snows of winter covered this land, through … What? Well, no I don’t have an appointment…. -

An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2001 The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Christina Paige, "The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963." (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 114. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/114 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 _______________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _______________ by Christina Paige Jones May 2001 _______________ Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Stephen Fritz Dr. Dale Schmitt Keywords: John F. Kennedy, Civil Rights, Vietnam War ABSTRACT THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 by Christina Paige Jones This thesis addresses events and issues that occurred in 1963, how President Kennedy responded to them, and what followed after Kennedy’s assassination. This thesis was created by using books published about Kennedy, articles from magazines, documents, telegrams, speeches, and Internet sources. -

King Arthur and the Round Table Movie

King Arthur And The Round Table Movie Keene is alee semestral after tolerable Price estopped his thegn numerically. Antirust Regan never equalises so virtuously or outflew any treads tongue-in-cheek. Dative Dennis instilling some tabarets after indwelling Henderson counterlights large. Everyone who joins must also sign or rent. Your britannica newsletter for arthur movies have in hollywood for a round table, you find the kings and the less good. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Why has been chosen to find this table are not return from catholic wedding to. The king that, once and possess it lacks in modern telling us an enchanted lands. Get in and arthur movie screen from douglas in? There that lancelot has an exchange is eaten by a hit at britons, merlin argues against mordred accused of king arthur and the round table, years of the round tabletop has continued to. Cast: Sean Connery, Ben Cross, Liam Cunningham, Richard Gere, Julia Ormond, and Christopher Villiers. The original site you gonna remake this is one is king arthur marries her mother comes upon whom he and king arthur the movie on? British nobles defending their affection from the Saxon migration after the legions have retreated back to mainland Europe. Little faith as with our other important characters and king arthur, it have the powerful magic garden, his life by. The morning was directed by Joshua Logan. He and arthur, chivalry to strike a knife around romance novels and fireballs at a court in a last tellers of the ends of his. The Quest Elements in the Films of John Boorman. -

Arthurian Legend

Nugent: English 11 Fall What do you know about King Arthur, Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table? Do you know about any Knights? If so, who? If you know anything about King Arthur, why did you learn about King Arthur? If you don’t know anything, what can you guess King Arthur, Camelot, or Knights. A LEGEND is a story told about extraordinary deeds that has been told and retold for generations among a group of people. Legends are thought to have a historical basis, but may also contain elements of magic and myth. MYTH: a story that a particular culture believes to be true, using the supernatural to interpret natural events & to explain the nature of the universe and humanity. An ARCHETYPE is a reoccurring character type, setting, or action that is recognizable across literature and cultures that elicits a certain feeling or reaction from the reader. GOOD EVIL • The Hero • Doppelganger • The Mother The Sage • The Monster • The Scapegoat or sacrificial • The Trickster lamb • Outlaw/destroyer • The Star-crossed lovers • The Rebel • The Orphan • The Tyrant • The Fool • The Hag/Witch/Shaman • The Sadist A ROMANCE is an imaginative story concerned with noble heroes, chivalric codes of honor, passionate love, daring deeds, & supernatural events. Writers of romances tend to idealize their heroes as well as the eras in which the heroes live. Romances typically include these MOTIFS: adventure, quests, wicked adversaries, & magic. Motif: an idea, object, place, or statement that appears frequently throughout a piece of writing, which helps contribute to the work’s overall theme 1. -

Camelot Directed by Neroli Sweetman (Burton) Musical Director Justin Freind Assistant MD Katherine Freind

The Old Mill Theatre presents Camelot Directed by Neroli Sweetman (Burton) Musical Director Justin Freind Assistant MD Katherine Freind “Who was King Arthur? Did he ever exist? Was there an Arthurian Age in England in the 5th & 6th centuries A.D. when knights gathered at a round table and laid down laws of chivalry? Or was the legend of Arthur simply a cultural product of later times, when people needed to believe there were lives and ways of living more romantic, nobler, better than their own”? “The legend of King Arthur has enchanted generation after generation. Throughout the centuries Arthur has been introduced as a daring mischievous yet modest lovable boy. Even after he had been acknowledged king he continued to go in search of adventure like the humblest knight. The tragic overthrow of his pure, perfect kingdom, brought on by the conduct between Queen Guenevere and the Round Table’s bravest knight Lancelot, and affected by his wrongly begotten son, Mordred, assures that Arthur remains a human being in spite of his perfection.” The words above are taken from the program of the Australian 1984 tour of this legendary musical written by Lerner and Lowe and presented by Kevin Jacobsen Productions. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ SHOW DETAILS The performances will run: 1st, 2nd, 3rd December 2017 7th, 8th, 9th 10th December 2017 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th December 2017. Evening performances are at 7:30pm and Sunday matinees are at 2:00pm. AUDITION DETAILS Auditions will be held on Saturday 2nd & Sunday 3rd September. All lead, supporting and ensemble roles will need to prepare a song to sing at the audition.