Strength Am D Suffering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure- Present State And

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present State and Future Potential By Claes Lykke Ragner FNI Report 13/2000 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Tittel/Title Sider/Pages Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present 124 State and Future Potential Publikasjonstype/Publication Type Nummer/Number FNI Report 13/2000 Forfatter(e)/Author(s) ISBN Claes Lykke Ragner 82-7613-400-9 Program/Programme ISSN 0801-2431 Prosjekt/Project Sammendrag/Abstract The report assesses the Northern Sea Route’s commercial potential and economic importance, both as a transit route between Europe and Asia, and as an export route for oil, gas and other natural resources in the Russian Arctic. First, it conducts a survey of past and present Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo flows. Then follow discussions of the route’s commercial potential as a transit route, as well as of its economic importance and relevance for each of the Russian Arctic regions. These discussions are summarized by estimates of what types and volumes of NSR cargoes that can realistically be expected in the period 2000-2015. This is then followed by a survey of the status quo of the NSR infrastructure (above all the ice-breakers, ice-class cargo vessels and ports), with estimates of its future capacity. Based on the estimated future NSR cargo potential, future NSR infrastructure requirements are calculated and compared with the estimated capacity in order to identify the main, future infrastructure bottlenecks for NSR operations. The information presented in the report is mainly compiled from data and research results that were published through the International Northern Sea Route Programme (INSROP) 1993-99, but considerable updates have been made using recent information, statistics and analyses from various sources. -

Living in Two Places : Permanent Transiency In

living in two places: permanent transiency in the magadan region Elena Khlinovskaya Rockhill Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge CB2 1ER, UK; [email protected] abstract Some individuals in the Kolyma region of Northeast Russia describe their way of life as “permanently temporary.” This mode of living involves constant movements and the work of imagination while liv- ing between two places, the “island” of Kolyma and the materik, or mainland. In the Soviet era people maintained connections to the materik through visits, correspondence and telephone conversations. Today, living in the Kolyma means living in some distant future, constantly keeping the materik in mind, without fully inhabiting the Kolyma. People’s lives embody various mythologies that have been at work throughout Soviet Kolyma history. Some of these models are being transformed, while oth- ers persist. Underlying the opportunities afforded by high mobility, both government practices and individual plans reveal an ideal of permanency and rootedness. KEYWORDS: Siberia, gulag, Soviet Union, industrialism, migration, mobility, post-Soviet The Magadan oblast’1 has enjoyed only modest attention the mid-seventeenth century, the history of its prishloye in arctic anthropology. Located in northeast Russia, it be- naseleniye3 started in the 1920s when the Kolyma region longs to the Far Eastern Federal Okrug along with eight became known for gold mining and Stalinist forced-labor other regions, okrugs and krais. Among these, Magadan camps. oblast' is somewhat peculiar. First, although this territory These regional peculiarities—a small indigenous pop- has been inhabited by various Native groups for centu- ulation and a distinct industrial Soviet history—partly ries, compared to neighboring Chukotka and the Sakha account for the dearth of anthropological research con- Republic (Yakutia), the Magadan oblast' does not have a ducted in Magadan. -

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North Stephanie Pezard, Abbie Tingstad, Kristin Van Abel, Scott Stephenson C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1731 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9745-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: NASA/Operation Ice Bridge. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Despite a period of generally heightened tensions between Russia and the West, cooperation on Arctic affairs—particularly through the Arctic Council—has remained largely intact, with the exception of direct mil- itary-to-military cooperation in the region. -

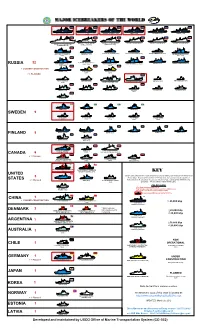

Visio-POLAR ICEBREAKERS Charts.Vsd

N N N N NNN SOVETSKIY SOYUZ (1990 REFIT 50 LET POBEDY (2007) ROSSIYA (1985 REFIT 2007) YAMAL (1993) VAYGACH (1990) TAYMYR (1989) 2007) N N N PROJECT L-60 (ESTIMATED PROJECT L-60 (ESTIMATED PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT L-110 (ESTIMATED COMPLETION 2015) COMPLETION 2016) COMPLETION 2017) PACIFIC ENTERPRISE (2006) PACIFIC ENDEAVOUR (2006) PACIFIC ENDURANCE (2006) AKADEMIK TRIOSHNIKOV VARANDAY (2008) KAPITAN DRANITSYN (1980 (2011) REFIT 1999) VLADIMIR IGNATYUK (1977 32 KRASIN (1976) ADMIRAL MAKAROV (1975) RUSSIA KAPITAN SOROKIN (1977 REFIT 1982) KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV KAPITAN NIKOLAYEV (1978) REFIT 1990) (1981) + 2 UNDER CONSTRUCTION YERMAK (1974) VITUS BERING ALEXEY CHIRIOV (2013) (2013) + 6 PLANNED SMIT SAKHALIN (1983) FESCO SAKHALIN SAKHALIN (2005) AKADEMIK FEDEROV (1987) SMIT SIBU (1983) (2005) VASILIY GOLOVNIN (1988) DIKSON (1983) MUDYUG (1982) MAGADAN (1982) KIGORIAK TALAGI (1978) DUDINKA (1970) (1979) TOR (1964) B B B ODEN (1989) ATLE (1974) FREJ (1975) YMER (1977) SWEDEN 9 B B B B B VIDAR VIKING NJORD VIKING LOKE VIKING TOR VIKING II BALDER VIKING (2001) (2011) (2011) (2001) (2001) B B B B B B FINLAND 8 NORDICA (1994) FENNICA (1993) KONTIO (1987) OTSO (1986) SISU (1976) URHO (1975) B B BOTNICA (1998) VOIMA (1954 REFIT 1979) LOUIS ST. LAURENT TERRY FOX JOHN G. DIEFENBAKER CANADA 6 (1969 REFIT 1993) (1983) (ESTIMATED COMPLETION 2017) + 1 Planned AMUNDSEN (ESTIMATED HENRY LARSEN DES GROSEILLIERS PIERRE RETURN TO SERVICE 2013) (1988) (1983) RADISSON (1978) POLAR SEA (REFIT 2006 INACTIVE POLAR STAR (1976 ESTIMATED 2011) KEY UNITED RETURN TO SERVICE 2014) Vessels were selected and organized based on their installed power measured in Brake Horse 5 Power (bhp). -

The Population History of Northeastern Siberia Since the Pleistocene

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/448829; this version posted October 22, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene Martin Sikora1,*, Vladimir V. Pitulko2,*, Vitor C. Sousa3,4,5,*, Morten E. Allentoft1,*, Lasse Vinner1, Simon Rasmussen6, Ashot Margaryan1, Peter de Barros Damgaard1, Constanza de la Fuente Castro1, Gabriel Renaud1, Melinda Yang7, Qiaomei Fu7, Isabelle Dupanloup8, Konstantinos Giampoudakis9, David Bravo Nogues9, Carsten Rahbek9, Guus Kroonen10,11, Michäel Peyrot11, Hugh McColl1, Sergey V. Vasilyev12, Elizaveta Veselovskaya12,13, Margarita Gerasimova12, Elena Y. Pavlova2,14, Vyacheslav G. Chasnyk15, Pavel A. Nikolskiy2,16, Pavel S. Grebenyuk17,18, Alexander Yu. Fedorchenko19, Alexander I. Lebedintsev17, Sergey B. Slobodin17, Boris A. Malyarchuk20, Rui Martiniano21,22, Morten Meldgaard1,23, Laura Arppe24, Jukka U. Palo25,26, Tarja Sundell27,28, Kristiina Mannermaa27, Mikko Putkonen25, Verner Alexandersen29, Charlotte Primeau29, Ripan Mahli30,31, Karl- Göran Sjögren32, Kristian Kristiansen32, Anna Wessman27, Antti Sajantila25, Marta Mirazon Lahr1,33, Richard Durbin21,22, Rasmus Nielsen1,34, David J. Meltzer1,35, Laurent Excoffier4,5, Eske Willerslev1,22,36** 1 - Centre for GeoGenetics, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5–7, 1350 Copenhagen, Denmark. 2 - Palaeolithic Department, Institute for the History of Material Culture RAS, 18 Dvortsovaya nab., 191186 St. Petersburg, Russia. 3 - Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal. -

The Unraveling of Russia's Far Eastern Power by Felix K

The Unraveling of Russia's Far Eastern Power by Felix K. Chang n the early hours of September 1, 1983, a Soviet Su-15 fighter intercepted and shot down a Korean Airlines Boeing 747 after it had flown over the I Kamchatka Peninsula. All 269 passengers and crew perished. While the United Statescondemned the act as evident villainyand the Soviet Union upheld the act as frontier defense, the act itselfunderscored the militarystrength Moscow had assembled in its Far Eastern provinces. Even on the remote fringes of its empire, strong and responsive militaryforces stood ready. As has been the case for much of the twentieth century, East Asia respected the Soviet Union and Russialargely because of their militarymight-with the economics and politics of the Russian Far East (RFE) playing important but secondary roles. Hence, the precipitous decline in Russia's Far Eastern forces during the 1990s dealt a serious blow to the country's power and influence in East Asia. At the same time, the regional economy's abilityto support itsmilitaryinfrastructure dwindled. The strikes, blockades, and general lawlessness that have coursed through the RFE caused its foreign and domestic trade to plummet. Even natural resource extraction, still thought to be the region's potential savior, fell victim to bureaucratic, financial, and political obstacles. Worse still, food, heat, and electricityhave become scarce. In the midst of this economic winter, the soldiers and sailors of Russia's once-formidable Far East contingent now languish in their barracks and ports, members of a frozen force.1 Political Disaggregation Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the RFE's political landscape has been littered with crippling conflicts between the center and the regions, among the 1 For the purposes of this article, the area considered to be the Russian Far East will encompass not only the administrative district traditionally known as the Far East, but also those of Eastern Siberia and Western Siberia. -

USSR (Pacific Ocean, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, and Bering Sea)

2 On February 7, 1984, the Soviet Council of Ministers declared a system of straight baselines for the Soviet east coast, including its coasts facing the Pacific Ocean, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, and Bering Sea.1 A translation of this decree follows. 4604 U.S.S.R. Declaration Of the baselines for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of the U.S.S.R. off the continental coast and islands of the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea. A decree of the U.S.S.R. Council of Ministers of February 7, 1984, approved a list of geographic coordinates of points which define the position of straight baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of the U.S.S.R. off the continental coast and islands of the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea is measured. The list is published below. LIST of geographic coordinates of points that determine the position of the straight baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (U.S.S.R. fishing zone) and continental shelf of the U.S.S.R. off the continental coast and islands of the Pacific Ocean, the Sea of Japan, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea is measured. A listing of geographic coordinates is then given. This list is provided in Annex 1 to this study. Following the list of coordinates the following concluding sentence appears in the decree: The same decree establishes that the waters of the Penzhinskaya Inlet north of the line connecting the southern islet off Cape Povorotnyy with Cape Dal'niy are, as waters of an historical bay, internal waters. -

Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chukot-TINRO, and Institute of Biological Problems of the North Far East Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report Open-File Report 2016–1108 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Images of walrus haulouts. A ground level view of an autumn haulout with adult females and young (Point Lay, Alaska, September, 25, 2013) is shown in the top panel. An aerial composite image of a large haulout with more than 1,000 male walruses is shown in the middle panel (Cape Greig, Alaska, May 3, 2016). A composite image of a very large haulout with tens of thousands of adult female walruses and their young is shown in the bottom panel in which the outlines of the haulout is highlighted in yellow (Point Lay, Alaska, August 26, 2011). Photo credits (top panel: Ryan Kingsbery, USGS; middle panel: Sarah Schoen, USGS; bottom panel: USGS). Pacific Walrus Coastal Haulout Database, 1852–2016—Background Report By Anthony S. Fischbach, Anatoly A. Kochnev, Joel L. Garlich-Miller, and Chadwick V. Jay Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Chukot-TINRO and Institute of Biological Problems of the North Far East Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences Open-File Report 2016–1108 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). -

USCG Icebreaker of the World

TES CO STA AS D T E GU IT A N R UN D N E M E S A S E R M I E N T E S T Y MAJOR ICEBREAKERS OF THE WORLD R ST A NSPORATION N N N N N N N N 50 Let Pobedy Sovetskiy Soyuz Rossiya Yamal Vaygach Taymyr L-60 L-60 (2007) (1990 refit 2014) (1985 refit 2007) (1993) (1990) (1989) ( 2015) (Estimated 2016) N N L-110 L-60 (Estimated 2017) (Estimated 2017) B B Vitus Bering Akademic Trioshnikov Varanda St. Petersburg Moskva Vladislav Strizhov Yuri Topchev Pacific Enterprise (2013) (2011) (2008) (2008) (2007) (2006) (2006) (2006) RUSSIA Pacific Endeavor Pacific Endurance Kapitan Dranitsyn Kapitan Sorokin Vladimir Ignatyuk Kapitan Khlebnikov Kapitan Nikolayev Krasin (36) (2006) (2006) (1980 refit 1999) (1977 refit 1990) (1977 refit 1982) (1981) (1978) (1976) + 5 under B B B construction Admiral Makarov Yermak Alexey Chiriov Project 2260 Project 21900M Project 21900M Project 21900M + 8 planned (1975) (1974) (2013) (2015) (2015) (Estimated 2015) (Estimated 2015) Fesco Sakhalin Vasiliy Golovnin Akademik Federov Ikaluk Smit Sakhalin Dikson Mudyug Magadan (2005) (1988) (1987) (1983) (1983) (1983) (1982) (1982) B B Kigoriak Talagi Dudinka Tor R-70202 R-70202 R-70202 R-70202 (1978) (1978) (1970) (1964) (2013) (2014) (2015) (2016) B B B Oden Ymer Frej Atle SWEDEN (1989) (1977) (1975) (1974) (7) Vidar Viking Tor Viking II Balder Viking (2001) (2011) (2011) B B B B FINLAND Nordica Fennica Kontio Otso Sisu Urho (7) (1994) (1993) (1987) (1986) (1976) (1975) B Voima (1954 refit 1979) CANADA Louis st. -

DEMUTH Bathsheba

The Walrus and the Bureaucrat: Energy, Ecology, and Making the State in the Russian and American Arctic, 1870–1950 BATHSHEBA DEMUTH Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/124/2/483/5426289 by guest on 24 February 2020 AT THE BERING STRAIT, less than sixty miles of ocean separates Russia’s Chukchi Penin- sula and the northwest coast of Alaska. Each winter, these narrows are bridged by ice. The Bering Sea appears to go still beneath its lid of frozen water. But the bergs and slush shelter colonies of hardy algae, and with spring, melt frees their photosynthetic potential, just as newly liquid water churns nutrient-heavy currents to the surface. The resulting bloom of phytoplankton nourishes creatures from minuscule crustaceans to gi- ant crabs, fish from salmon and sole to cod and herring. By summer, the Pacific Flyway brings birds by the millions to feed where whale dives froth krill to the surface. Among this riot of life are over 100,000 Odobenus rosmarus divergens,thePacificwalrus.1 Even in summer, enough ice remains to provide refuge for the walrus herds, floating them close to the seafloor mollusks that bulk their bodies to a ton or more. A walrus can live as long as forty years. Thus a pup born in the 1870s came of age in a Bering Strait newly divided between the United States and Imperial Russia, and gave birth to her last pups in the years before Lenin came out of exile. Both generations bore half-submerged witness to human revolutions onshore. The United States and Imperial Russia began patrolling the Bering Strait, the First World War came and went, a new So- viet state arrived in Russia, a second world war began and then dwindled to its frigid af- termath. -

Magadan Oblast 460,246 Sq

MAGADAN 258 By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST Map 7.1 Magadan Oblast 460,246 sq. km Russian Far East SEVERO-EVENSKY SAKHA Verkhne-Paren SREDNEKANSKY OMSUKCHANSKY Balygychan Start Y Oktyabrina Garmanda Gizhiga Dukat Omsukchan SUSUMANSK Ozernoe Seimchan Galimyi Burkandya Taskan Verkhny Seimchan Topolyovka Elgen Shiroky Shturmovoi Ust-Taskan Merenga Maldyak Kadykchan Myaundzha Khatyngnakh Ust-Srednekan Belichan Susuman Verkhny At-Yuryakh Adygalakh ! Orotukan Kupka !Yagodnoe Bolshevik Kholodny Burkhala Debin Spornoe Nexikan Strelka !Sinegorie Orotuk YAGODNINSKY Mariny Raskovoi Obo Myakit Vetrenyi k Kulu Talaya s t Omchak KHASYNSKY o Nelkoba Ust-Omchug Atka h NTE KI ! NSKY Takhtoyamsk k O Madaun Yablonevy f OLSKY o Karamken Palatka Yamsk a Stekolny ! e Sokol S OLSKY Uptar Klepka Ola Tauisk Arman ! Talon P! Balagannoe MAGADAN ¯ Sheltinga km 100 KORYAKIA Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 7 Magadan Oblast Location Magadan Oblast lies on the northwestern shores of the Sea of Okhotsk. The Chukotsky and Koryak Autonomous Okrugs border on the north; to the south is Khabarovsk Krai, and to the west lies the Republic of Sakha. Size 460,246 sq. km, or about six percent of the Russian Federation. The total area of cities and villages is 62,700 ha, or less than 0.00014 percent of the oblast. Climate The arctic and subarctic climate is infl uenced by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the cold Sea of Okhotsk to the east, and the continental terrain of Sakha to the west. -

Bearing Black: Russia's Military Power in the Indo-Asia-Pacific

SPECIAL REPORT BEARing back Russia’s military power in the Indo-Asia–Pacific under Vladimir Putin Alexey D Muraviev January 2018 Alexey D Muraviev Dr Alexey D Muraviev is Head of Department of Social Sciences and Security Studies at Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia. He is an Associate Professor of National Security and International Relations, founder and Director of the Strategic Flashlight forum on national security and strategy at Curtin. He has published widely on matters of national and international security. His research interests include problems of modern maritime power, contemporary defence and strategic policy, Russia’s strategic and defence policy, Russia as a Pacific power, transnational terrorism, Australian national security, and others. Alexey is a member of the Australian Member Committee, Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region (AU-CSCAP); member of Russia-NATO Experts Group; member of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London; reviewer of the Military Balance annual defence almanac; member of the advisory board, CIVSEC 2018 international congress and exposition, member of the Advisory Board, Australia Public Network, member of the Research Network for Secure Australia, and other organisations and think tanks. In 2011, Alexey was the inaugural scholar-in residence at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. In 2007, 2008, 2009 and 2010, the Australian Research Council (ARC) College of Experts has nominated Dr Muraviev as an “expert of international standing”. He advises members of state and federal parliaments on foreign policy and national security matters and is frequently interviewed by state, national and international media. About ASPI ASPI’s aim is to promote Australia’s security by contributing fresh ideas to strategic decision‑making, and by helping to inform public discussion of strategic and defence issues.