DEMUTH Bathsheba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure- Present State And

Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present State and Future Potential By Claes Lykke Ragner FNI Report 13/2000 FRIDTJOF NANSENS INSTITUTT THE FRIDTJOF NANSEN INSTITUTE Tittel/Title Sider/Pages Northern Sea Route Cargo Flows and Infrastructure – Present 124 State and Future Potential Publikasjonstype/Publication Type Nummer/Number FNI Report 13/2000 Forfatter(e)/Author(s) ISBN Claes Lykke Ragner 82-7613-400-9 Program/Programme ISSN 0801-2431 Prosjekt/Project Sammendrag/Abstract The report assesses the Northern Sea Route’s commercial potential and economic importance, both as a transit route between Europe and Asia, and as an export route for oil, gas and other natural resources in the Russian Arctic. First, it conducts a survey of past and present Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo flows. Then follow discussions of the route’s commercial potential as a transit route, as well as of its economic importance and relevance for each of the Russian Arctic regions. These discussions are summarized by estimates of what types and volumes of NSR cargoes that can realistically be expected in the period 2000-2015. This is then followed by a survey of the status quo of the NSR infrastructure (above all the ice-breakers, ice-class cargo vessels and ports), with estimates of its future capacity. Based on the estimated future NSR cargo potential, future NSR infrastructure requirements are calculated and compared with the estimated capacity in order to identify the main, future infrastructure bottlenecks for NSR operations. The information presented in the report is mainly compiled from data and research results that were published through the International Northern Sea Route Programme (INSROP) 1993-99, but considerable updates have been made using recent information, statistics and analyses from various sources. -

Circumpolar Inuit Economic Summit

VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1, MARCH 2017 Inupiaq: QILAUN Siberian Yupik: SAGUYA Summit Participants. Photo by Vernae Angnaboogok Central Yupik: CAUYAQ UPCOMING EVENTS Circumpolar Inuit Economic Summit April 1-3 ICC Executive Council Meeting • Utqiagvik, By ICC Alaska Staff Alaska • www.iccalaska.org April 6 At the first international gathering of Inuit in June 1977 at Barrow, Alaska, First Alaskans Institute: Indigenous the Committee for Original Peoples’ Entitlement (COPE) offered up two Research Workshop • Fairbanks, Alaska • www.firstalaskans.org resolutions concerning cross-border trade among Inuit. April 11-12 Bethel Decolonization Think-Tank • Bethel, The first resolution called for a sub-committee with representatives from each Alaska • www.iccalaska.org region to investigate and report on possible new economic opportunities and April 7-9 Alaska Native Studies Conference • Fairbanks, trade routes. It stated that the discovery of oil and gas and our ownership Alaska • www.alaskanativestudies.org or royalties provided capital needed for reinvesting in and promoting Inuit April 24-27 industry. International Conference on Arctic Science: Bringing Knowledge to Action • Reston, Virginia • www.amap.no The second resolution called for a sub-committee on energy to investigate the May 10 feasibility of a circumpolar Inuit energy policy. These two resolutions were I AM INUIT Exhibit Event at the UAF Art Gallery tabled nearly forty years ago by the Inuvialuit of western Canada. • Fairbanks, Alaska • www.iaminuit.org May 11 In 1993, ICC held an Inuit Business Development Conference in Anchorage, 10th Annual Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting • Fairbanks, Alaska • Alaskan to discuss: trade and travel; strengthening economic ties and; natural www.arctic-council.org resources and economies. -

A Customs Guide to Alaska Native Arts

What International travellers, shop owners and artisans need to know A Customs Guide to Alaska Native Arts Photo Credits: Alaska Native Arts Foundation Updated: June 2012 Table of Contents Cover Page Art Credits……………………………………….……………..………………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 USING THE GUIDE ................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 MARINE MAMMAL HANDICRAFTS - Significantly Altered .............................................................................................................. 3 COUNTRY INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 In General (For countries other than those listed specifically in this guide) ............................................................................... 4 Australia ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Canada ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 European Union ................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Living in Two Places : Permanent Transiency In

living in two places: permanent transiency in the magadan region Elena Khlinovskaya Rockhill Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge CB2 1ER, UK; [email protected] abstract Some individuals in the Kolyma region of Northeast Russia describe their way of life as “permanently temporary.” This mode of living involves constant movements and the work of imagination while liv- ing between two places, the “island” of Kolyma and the materik, or mainland. In the Soviet era people maintained connections to the materik through visits, correspondence and telephone conversations. Today, living in the Kolyma means living in some distant future, constantly keeping the materik in mind, without fully inhabiting the Kolyma. People’s lives embody various mythologies that have been at work throughout Soviet Kolyma history. Some of these models are being transformed, while oth- ers persist. Underlying the opportunities afforded by high mobility, both government practices and individual plans reveal an ideal of permanency and rootedness. KEYWORDS: Siberia, gulag, Soviet Union, industrialism, migration, mobility, post-Soviet The Magadan oblast’1 has enjoyed only modest attention the mid-seventeenth century, the history of its prishloye in arctic anthropology. Located in northeast Russia, it be- naseleniye3 started in the 1920s when the Kolyma region longs to the Far Eastern Federal Okrug along with eight became known for gold mining and Stalinist forced-labor other regions, okrugs and krais. Among these, Magadan camps. oblast' is somewhat peculiar. First, although this territory These regional peculiarities—a small indigenous pop- has been inhabited by various Native groups for centu- ulation and a distinct industrial Soviet history—partly ries, compared to neighboring Chukotka and the Sakha account for the dearth of anthropological research con- Republic (Yakutia), the Magadan oblast' does not have a ducted in Magadan. -

Ancient DNA Reveals the Chronology of Walrus Ivory Trade from Norse Greenland

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title: Ancient DNA reveals the chronology of walrus ivory trade from Norse Greenland Short title: Tracing the medieval walrus ivory trade Bastiaan Star1*†, James H. Barrett2*†, Agata T. Gondek1, Sanne Boessenkool1* * Corresponding author † These authors contributed equally 1 Centre for Ecological and Evoluionary Synthesis, Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, PO Box 1066, Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3ER, United Kingdom. Keywords: High-throughput sequencing | Viking Age | Middle Ages | aDNA | Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/289165; this version posted March 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The search for walruses as a source of ivory –a popular material for making luxury art objects in medieval Europe– played a key role in the historic Scandinavian expansion throughout the Arctic region. Most notably, the colonization, peak and collapse of the medieval Norse colony of Greenland have all been attributed to the proto-globalization of ivory trade. -

Strength Am D Suffering

AID TO THE CHURCH IN NEED FR. MICHAEL SHIELDS, JOHN NEWTON & TERRY MURPHY Strength am d Suffering StrengthTHE MARTYRS am OFd SufferingMAGADAN Martyrs of Magadan - Memories from the Gulag © 2007 Aid to the Church in Need All rights reserved Web version: Strength Amid Suffering - The Martyrs of Magadan © 2015 Aid to the Church in Need All rights reserved Testaments collated by Fr Michael Shields Text edited by John Newton and Terry Murphy Design by Ronan Lynch Via Crucis images courtesy of ACN Italy. Photographs courtesy of Patrick Delapierre/Church of the Nativity of Christ, Magadan, Russia and the private collections of survivors of the camps. Published by Aid to the Church in Need (Ireland) www.acnireland.org FR. MICHAEL SHIELDS, JOHN NEWTON & TERRY MURPHY Strength am d Suffering “People died by the tens, hundreds and thousands. In their place always came new silent slaves, who laboured for some food, a piece of bread. “They died and they were quietly buried. No one had a burial service for them, no family or friends paid their last respects. They did not even dig graves for them, but rather dug a communal trench. And they tossed the naked bodies in the snow and when spring came, wild animals tore apart their bones. “We who managed to survive mourned them. We believe that the Lord accepted these martyrs into the heavenly kingdom. “May all these peoples’ memory live on forever.” OLGA ALEXSEIEVNA GUREEVA Prisoner in the gulag camps for 11 years THE MARTYRS OF MAGADAN AID TO THE CHURCH IN NEED “In this unmarked grave our lives have ended. -

The Ivory Trade: the Single Greatest Threat to Wild Elephants

THE IVORY TRADE: THE SINGLE GREATEST THREAT TO WILD ELEPHANTS Elephants have survived in the wild for 15 million years, but today this iconic species is threatened with extinction due to ongoing poaching for ivory. As long as there is demand for ivory, elephants will continue to be killed for their tusks. According to best estimates, as many as 26,000 elephants are killed every year simply to extract their tusks. A Brief History of the Ivory Trade Demand for ivory first skyrocketed in the 1970s and 1980s. The trade in ivory was legal then -- although for the most part it was taken illegally. During those decades, approximately 100,000 elephants per year were being killed. The toll on African elephant populations was shocking: over the course of a single decade, their numbers dropped by half. In October of 1989 the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) voted to move African elephants from Appendix II to Appendix I, affording the now highly endangered animal the maximum level of protection, effectively ending trade in all elephant parts, including ivory. With the new Appendix 1 listing, the poaching of elephants literally stopped overnight. The ban brought massive awareness of the plight of elephants, the bottom dropped out of the market, and prices plummeted. Ivory was practically unsellable. For 10 years, the global ban stood strong and it seemed the crisis had ended. Elephant numbers began to recover. Unfortunately, the resurgence in elephant populations, while nowhere near the numbers prior to the spike in trade, was nevertheless a catalyst for some African countries to consider reopening the trade. -

Viking Age Settlement and Medieval Walrus Ivory Trade in Iceland and Greenland

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hunter College 2015 Was it for walrus? Viking Age settlement and medieval walrus ivory trade in Iceland and Greenland Karen M. Frei National Museum of Denmark Ashley N. Coutu University of Cape Town Konrad Smiarowski CUNY Graduate Center Ramona Harrison CUNY Hunter College Christian K. Madsen National Museum of Denmark See next page for additional authors How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_pubs/637 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Authors Karen M. Frei, Ashley N. Coutu, Konrad Smiarowski, Ramona Harrison, Christian K. Madsen, Jette Arneborg, Robert Frei, Gardar Guðmundsson, Søren M. Sindbækg, James Woollett, Steven Hartman, Megan Hicks, and Thomas McGovern This article is available at CUNY Academic Works: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_pubs/637 Was it for walrus? Viking Age settlement and medieval walrus ivory trade in Iceland and Greenland Karin M. Frei, Ashley N. Coutu, Konrad Smiarowski, Ramona Harrison, Christian K. Madsen, Jette Arneborg, Robert Frei, Gardar Guðmundsson, Søren M. Sindbæk, James Woollett, Steven Hartman, Megan Hicks and Thomas H. McGovern Abstract Walrus-tusk ivory and walrus-hide rope were highly desired goods in Viking Age north-west Europe. New finds of walrus bone and ivory in early Viking Age contexts in Iceland are concentrated in the south-west, and suggest extensive exploitation of nearby walrus for meat, hide and ivory during the first century of settlement. -

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North Stephanie Pezard, Abbie Tingstad, Kristin Van Abel, Scott Stephenson C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1731 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9745-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: NASA/Operation Ice Bridge. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Despite a period of generally heightened tensions between Russia and the West, cooperation on Arctic affairs—particularly through the Arctic Council—has remained largely intact, with the exception of direct mil- itary-to-military cooperation in the region. -

Trophics, and Historical Status of the Pacific Walrus

MODERN POPULATIONS, MIGRATIONS, DEMOGRAPHY, TROPHICS, AND HISTORICAL STATUS OF THE PACIFIC WALRUS by Francis H. Fay with Brendan P. Kelly, Pauline H. Gehnrich, John L. Sease, and A. Anne Hoover Institute of Marine Science University of Alaska Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 611 September 1984 231 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page ABSTRACT. .237 LIST OF TABLES. c .239 LIST OF FIGURES . .243 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ● . ● . ● . ● . 245 I. INTRODUCTION. ● ● . .246 A. General Nature and Scope of Study . 246 1. Population Dynamics . 246 2. Distribution and Movements . 246 3. Feeding. .247 4. Response to Disturbance . 247 B. Relevance to Problems of Petroleum Development . 248 c. Objectives. .248 II. STUDY AREA. .250 111. SOURCES, METHODS, AND RATIONALE OF DATA COLLECTION . 250 A. History of the Population . 250 B. Distribution and Composition . 251 c. Feeding Habits. .255 D. Effects of Disturbance . 256 IV. RESULTS . .256 A. Historical Review . 256 1. The Russian Expansion Period, 1648-1867 . 258 2. The Yankee Whaler Period, 1848-1914 . 261 233 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Section w 3. From Depletion to Partial Recovery, 1900-1935 . 265 4. The Soviet Exploitation Period, 1931-1962 . 268 5. The Protective Period, 1952-1982 . 275 B. Distribution and Composition . 304 1. Monthly Distribution . 304 2. Time of Mating . .311 3. Location of the Breeding Areas . 312 4. Time and Place of Birth . 316 5. Sex/Age Composition . 318 c. Feeding Habits. .325 1. Winter, Southeastern Bering Sea . 325 2. Winter, Southwestern Bering Sea . 330 3. Spring, Eastern Bering Sea . 330 4. Summer , Chukchi Sea . .337 5. Amount Eaten in Relation to Age, Sex, Season . -

HAULING OUT: International Trade and Management of Walrus

HAULING OUT: International Trade and Management of Walrus Tanya Shadbolt, Tom Arnbom, & Ernest W. T. Cooper A TRAFFIC REPORT HaulingOut_REPORT_FINAL.indd 1 2014-05-13 6:21 PM © 2014 World Wildlife Fund. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9693730-9-4 All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit TRAFFIC. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Shadbolt, T., Arnbom, T. and Cooper, E.W.T. (2014). Hauling Out: International Trade and Management of Walrus. TRAFFIC and WWF-Canada. Vancouver, B.C. Cover photo: Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens) males hauled out at Round Island, Alaska, United States © Kevin Schafer/WWF-Canon HaulingOut_REPORT_FINAL.indd 2 2014-05-13 6:21 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents i Acknowledgements v Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Purpose of the report -

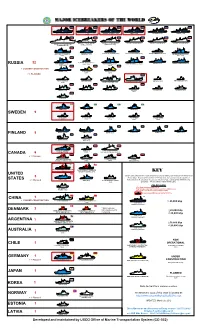

Visio-POLAR ICEBREAKERS Charts.Vsd

N N N N NNN SOVETSKIY SOYUZ (1990 REFIT 50 LET POBEDY (2007) ROSSIYA (1985 REFIT 2007) YAMAL (1993) VAYGACH (1990) TAYMYR (1989) 2007) N N N PROJECT L-60 (ESTIMATED PROJECT L-60 (ESTIMATED PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT 21900 M (2016) PROJECT L-110 (ESTIMATED COMPLETION 2015) COMPLETION 2016) COMPLETION 2017) PACIFIC ENTERPRISE (2006) PACIFIC ENDEAVOUR (2006) PACIFIC ENDURANCE (2006) AKADEMIK TRIOSHNIKOV VARANDAY (2008) KAPITAN DRANITSYN (1980 (2011) REFIT 1999) VLADIMIR IGNATYUK (1977 32 KRASIN (1976) ADMIRAL MAKAROV (1975) RUSSIA KAPITAN SOROKIN (1977 REFIT 1982) KAPITAN KHLEBNIKOV KAPITAN NIKOLAYEV (1978) REFIT 1990) (1981) + 2 UNDER CONSTRUCTION YERMAK (1974) VITUS BERING ALEXEY CHIRIOV (2013) (2013) + 6 PLANNED SMIT SAKHALIN (1983) FESCO SAKHALIN SAKHALIN (2005) AKADEMIK FEDEROV (1987) SMIT SIBU (1983) (2005) VASILIY GOLOVNIN (1988) DIKSON (1983) MUDYUG (1982) MAGADAN (1982) KIGORIAK TALAGI (1978) DUDINKA (1970) (1979) TOR (1964) B B B ODEN (1989) ATLE (1974) FREJ (1975) YMER (1977) SWEDEN 9 B B B B B VIDAR VIKING NJORD VIKING LOKE VIKING TOR VIKING II BALDER VIKING (2001) (2011) (2011) (2001) (2001) B B B B B B FINLAND 8 NORDICA (1994) FENNICA (1993) KONTIO (1987) OTSO (1986) SISU (1976) URHO (1975) B B BOTNICA (1998) VOIMA (1954 REFIT 1979) LOUIS ST. LAURENT TERRY FOX JOHN G. DIEFENBAKER CANADA 6 (1969 REFIT 1993) (1983) (ESTIMATED COMPLETION 2017) + 1 Planned AMUNDSEN (ESTIMATED HENRY LARSEN DES GROSEILLIERS PIERRE RETURN TO SERVICE 2013) (1988) (1983) RADISSON (1978) POLAR SEA (REFIT 2006 INACTIVE POLAR STAR (1976 ESTIMATED 2011) KEY UNITED RETURN TO SERVICE 2014) Vessels were selected and organized based on their installed power measured in Brake Horse 5 Power (bhp).