D.H. LAWRENCE and FICTIONAL REPRESENTATIONS of BLOOD-CONSCIOUSNESS By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

A Study of the Captain's Doll

A Study of The Captain’s Doll 論 文 A Study of The Captain’s Doll: A Life of “a Hard Destiny” YAMADA Akiko 要 旨 英語題名を和訳すると,「『大尉の人形』研究──「厳しい宿命」の人 生──」になる。1923年に出版された『大尉の人形』は『恋する女たち』, 『狐』及び『アルヴァイナの堕落』等の小説や中編小説と同じ頃に執筆さ れた D. H. ロレンスの中編小説である。これらの作品群は多かれ少なかれ 類似したテーマを持っている。 時代背景は第一次世界大戦直後であり,作品の前半の場所はイギリス軍 占領下のドイツである。主人公であるヘプバーン大尉はイギリス軍に所属 しておりドイツに来たが,そこでハンネレという女性と恋愛関係になる。し かし彼にはイギリスに妻子がいて,二人の情事を噂で聞きつけた妻は,ドイ ツへやってきて二人の仲を阻止しようとする。妻は,生計を立てるために人 形を作って売っていたハンネレが,愛する大尉をモデルにして作った人形 を見て,それを購入したいと言うのだが,彼女の手に渡ることはなかった。 妻は事故で死に,ヘプバーンは新しい人生をハンネレと始めようと思う が,それはこれまでの愛し愛される関係ではなくて,女性に自分を敬愛し 従うことを求める関係である。筆者は,本論において,この関係を男性優 位の関係と捉えるのではなくて,ロレンスが「星の均衡」の関係を求めて いることを論じる。 キーワード:人形的人間,月と星々,敬愛と従順,魔力,太陽と氷河 1 愛知大学 言語と文化 No. 38 Introduction The Captain’s Doll by D. H. Lawrence was published in 1923, and The Fox (1922) and The Ladybird (1923) were published almost at the same time. A few years before Women in Love (1920) and The Lost Girl (1921) had been published, too. These novellas and novels have more or less a common theme which is the new relationship between man and woman. The doll is modeled on a captain in the British army occupying Germany after World War I. The maker of the doll is a refugee aristocrat named Countess Johanna zu Rassentlow, also called Hannele, a single woman. She is Captain Hepburn’s mistress. His wife and children live in England. Hannele and Mitchka who is Hannele’s friend and roommate, make and sell dolls and other beautiful things for a living. Mitchka has a working house. But the captain’s doll was not made to sell but because of Hannele’s love for him. The doll has a symbolic meaning in that he is a puppet of both women, his wife and his mistress. -

DHLSNA Newsletter November 2011

The Newsletter of the D. H. Lawrence Society of North America Fall 2011, Vol. 41 Letter from DHLSNA President Welcome to the A bright winter noonday sun in Thirroul, a brisk wind, cold salt waves on a wide beach online Newsletter! below the bluff on which Wyewurk still stands—swimming in the same sea Lawrence We hope you enjoy this Fall 2011 and Frieda swam in—how can this already be four months ago? issue. --Julianne Newmark It is, though—and as you can see in this issue from Nancy Paxton’s report on the DHLSNA Newsletter Editor 12th International D. H. Lawrence Conference, the gathering in Sydney of Lawrence scholars from eleven countries (England, Wales, Korea, Japan, India, the United States, Canada, Indonesia, Sweden, South Africa, and Australia) was a resounding success. Take a look at the conference program online if you have any doubts. Log-in information This Fall 2011 newsletter is testimony to the thriving interest in and study of Lawrence for DHLSNA that persists all over the world, in conferences past and future (from Louisville to Paris to Taos to Seattle, from Sydney to Gargnano), carried on by an international website community of extraordinary liveliness, generosity, and kindness. Is it possible that an Login for 2011: interest in Lawrence shapes personalities? Maybe privately we’re all prone to the Username = dhlsna occasional Lawrentian outburst, but I find that hard to believe--I’m more willing to Password = porcupine believe that Lawrence’s challenges to traditional epistemologies, to the ruse of http://dhlsna.com/Directory.htm “objectivity” in academia, attracts scholars whose modesty, whose awareness of their bodily limitations and their situatedness in time and space, makes them particularly supportive of younger scholars, of those whose work will one day surpass their own. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

Warren Roberts

Warren Roberts: A Container List of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Roberts, Warren, 1916-1998 Title: Warren Roberts Papers Dates: 1903-1985 Extent: 33 record storage cartons, 1 oversize box (35 linear feet) Abstract: The Warren Roberts Papers contain materials primarily concerning his research and writing on D. H. Lawrence, including correspondence, research materials on Lawrence consisting of many photocopied letters and Lawrence works, Ransom Center related materials, and academic materials. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03557 Language: English Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Part or all of this collection is housed off-site and may require up to three business days’ notice for access in the Ransom Center’s Reading and Viewing Room. Please contact the Center before requesting this material: [email protected] Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. Restrictions on Authorization for publication is given on behalf of the University of Use: Texas as the owner of the collection and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder which must be obtained by the researcher. -

Kan Herbals Formula Guide

FORMULA GUIDE Chinese Herbal Products You Can Trust Kan Herbals – Formulas by Ted Kaptchuk, O.M.D. Written and researched by Ted J. Kaptchuk, O.M.D.; Z’ev Rosenberg, L.Ac. Copyright © 1992 by Sanders Enterprises with revisions of text and formatting by Kan Herb Company. Copyright © 1996 by Andrew Miller with revisions of text and formatting by Kan Herb Company. Copyright © 2008 by Lise Groleau with revisions of text and formatting by Kan Herb Company. All rights reserved. No part of this written material may be reproduced or stored in any retrieval system, by any means – photocopy, electronic, mechanical or otherwise – for use other than “fair use,” without written consent from the publisher. Published by Golden Mirror Press, California. Printed in the United States of America. First Edition, June 1986 Revised Edition, October 1988 Revised Edition, May 1992 Revised Edition, November 1994 Revised Edition, April 1996 Revised Edition, January 1997 Revised Edition, April 1997 Revised Edition, July 1998 Revised Edition, June 1999 Revised Edition, June 2002 Revised Edition, July 2008 Revised Edition, February 2014 Revised Edition, January 2016 FORMULA GUIDE 25 Classical Chinese Herbal Formulas Adapted by Ted Kaptchuk, OMD, LAc Contents Product Information.....................................................................................................................................1 Certificate of Analysis Sample .................................................................................................................6 High Performance -

Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY D.H. LAWRENCE RANCH HISTORIC DISTRICT HISTORIC NAME: Kiowa Ranch OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: Lobo Ranch, Flying Heart Ranch 2. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER: Lawrence Road, approx. 2 3/4 miles east of NM NOT FOR PUBLICATION: N/A Hwy 522 on U.S. Forest Service Rd. 7 CITY OR TOWN: San Cristobal VICINITY: X STATE: New Mexico CODE: NM COUNTY: Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564 3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_nomination __request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _X_nationally ^locally. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __meets does not meet the National Register criteria. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this property is: Signature of the Keeper Date of Action . entered in the National Register c f __ See continuation sheet. / . determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. -

Tongues on Fire: on the Origins and Transmission of a System of Tongue Diagnosis

Tongues on Fire: On the Origins and Transmission of a System of Tongue Diagnosis Nancy Holroyde-Downing University College London A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of University College London In Partial Fulflment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Department of History 2017 I, Nancy Holroyde-Downing, confrm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confrm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Abstract Tongues on Fire: Te Origins and Development of a System of Tongue Diagnosis Tis dissertation explores the origins and development of a Chinese diagnostic system based on the inspection of the tongue, and the transmission of this practice to Europe in the late 17th century. Drawing on the rich textual history of China, I will show that the tongue is cited as an indicator of illness or a portent of death in the classic texts of the Han dynasty, but these references do not amount to a system of diagnosis. I will argue that the privileging of the tongue as a diagnostic tool is a relatively recent occurrence in the history of Chinese medicine. Paying particular attention to case records kept by physicians from the Han dynasty (206 bce–220 ce) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), I will show that an increasing interest in the appearance of the tongue was specifcally due to its ability to refect the presence and intensity of heat in the body. Tongue inspection’s growing pervasiveness coincided with an emerging discourse among Chinese physicians concerning the relative usefulness of shang- han 傷寒 (Cold Damage) or wenbing 溫病 (Warm Disease) theories of disease progression. -

D. H. Lawrence D

D. H. Lawrence D. H. Lawrence A Literary Life John Worthen Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-0-333-43353-9 ISBN 978-1-349-20219-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20219-5 © John Worthen 1989, 1993 All rights reserved. For information write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1989 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worthen, John. D.H. Lawrence: a literary life / John Worthen. p. cm. - (Literary lives) Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-312-03524-2 (hc) ISBN 978-0-312-08752-4 (pbk.) 1. Lawrence, D.H. (David Herbert), 1885-1930. 2. Authors, English-20th century-Biography. I Title. II. Series: Literary lives (New York, N.Y.) PR6023.A93Z955 1993 823'.912-dc20 92-41758 IB] CIP First Paperback Edition: March 1993 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ToConni 1 hope to God 1 shall be able to make a living - but there, one must. (Lawrence to Edward Garnett, 18 February 1913) 1 am reading the Life. It is interesting, but also false: far too jammy. Voltaire had made, acquired for himself, by the time he was my age, an income of £3,000 - equivalent at least to an income of twelve thousand pounds, today. How had he done it? - it means a capital of two hundred thousand pounds. Where had it come from? (Lawrence to Dorothy Brett, 24 November 1926) We talked my poverty - it has got on my nerves lately. -

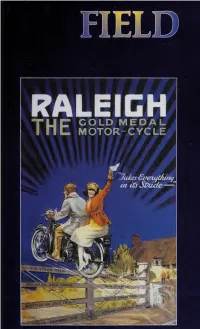

FIELD, Issue 82, Spring 2010

RALEIGH COLD MEDAL MOTOR-CYCLE V ' i . trial ^USTRIAI pTogfil TRIAlS ’TT FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 82 SPRING 2010 OBERLIN COLLEGE PRESS EDITORS David Young David Walker ASSOCIATE Pamela Alexander EDITORS DeSales Harrison EDITOR-AT- Martha Collins LARGE MANAGING Linda Slocum EDITOR EDITORIAL Nicholas Guren ASSISTANT DESIGN Steve Farkas www.oberlin.edu/ocpress Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Subscriptions and manuscripts should be sent to FIELD, Oberlin College Press, 50 North Professor Street, Oberlin, OH 44074. Man¬ uscripts will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped self-addressed envelope. Subscriptions $16.00 a year / $28.00 for two years / $40.00 for three years. Single issues $8.00 postpaid. Please add $4.00 per year for Canadian addresses and $9.00 for all other countries. Back issues $12.00 each. Contact us about availability. FIELD is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Copyright © 2010 by Oberlin College. ISSN: 0015-0657 CONTENTS Bob Hicok 7 Forays into life saving 9 School days Dore Kiesselbach 10 Song 11 Umpire Jesse Lee Kercheval 12 Letter in an Envelope Laura Shoemaker 13 Instances of Generosity 14 Forcing House Olvido Garcia Valdes 15 Came Translated by 16 Listens Catherine Hammond 17 We Frannie Lindsay 18 Sixty Philip Metres 19 from Along the Shrapnel Edge of Maps Dixon J. Jones 23 Repatriarch 25 Elliott Highway Rebecca Hazelton 26 [This heart that broke so long] 27 [Such are the inlets of the mind —] Ryan Boyd 28 This Was How She Came to Dinner Eric Pankey 29 The Creation of Adam 30 As of Yet Michael Dickman 31 Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Untitled Angela Ball 33 Lots of Swearing at the Fairgrounds 34 The Little Towns Hoist on One Shoulder Heather Sellers 35 Woman without a man with a bicycle without a fish Sarah M. -

Appendix: Lawrence's Sexuality and His Supposed 'Fascism'

Appendix: Lawrence’s Sexuality and his Supposed ‘Fascism’ The vexed question of Lawrence’s sexuality is exacerbated by the fact that in his lifetime any published evidence was likely to be affected by the need to avoid hostile legislation. It is clear that he was sometimes attracted by other men, this being evident from the chapter in The White Peacock where Cyril expresses his delight in George Saxton’s ath- letic body and reflects our love was perfect for a moment, more perfect than any love I have known since, either for man or woman.1 The sentiment is echoed in the unpublished ‘Prologue’ that formed the opening chapter to Women in Love. In this he noted the fact that he was rarely attracted by women, but often by men—who in such cases belonged mainly to two groups: on the one hand some who were fair, Northern, blue-eyed, crystalline, on the other, dark and viscous. In spite of this, however, there was no admission of active homo- sexuality.2 Previously, his remarks on homosexuality were extremely hostile, as witnessed by his remarks concerning the young men who gathered round John Maynard Keynes at Cambridge and the soldiers he witnessed on the sea-front in Worthing in 1915.3 Knud Merrild, who lived close to Lawrence for the winter of 1922–3, was adamant that Lawrence showed no signs of homosexuality whatever.4 In the novel Women in Love, Birkin engages in the well-known incident of wrestling with Gerald Crich, but this appears to be the closest they get to the formation of a physical relationship. -

Lawrence's Dualist Philosophy

The Plumed Serpent: D. H. Lawrence's Transitional Novel by Freda R. Hankins A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Humanities in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida April 1985 The Plumed Serpent: D. H. Lawrence's Transitional Novel by Freda R. Hankins This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr. William Coyle, Department of English, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the College of Humanities and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Chairperson Date ii ABSTRACT Author: Freda R. Hankins Title: The Plumed Serpent: D. H. Lawrence's Transitional Novel Institution: Florida Atlantic University Degree: Master of Arts Year: 1985 The life and the philosophy of D. H. Lawrence influenced his novels. The emotional turmoil of his life, his obsession with perfecting human relationships, and his fascination with the duality of the world led him to create his most experimental and pivotal novel, The Plumed Serpent. In The Plumed Serpent Lawrence uses a superstructure of myth to convey his belief in the necessity for the rebirth of a religion based on the dark gods of antiquity; coupled with this was his fervent belief that in all matters, sexual or spiritual, physical or emotional, political or religious, men should lead and women should follow. Through a study of Lawrence's life and personal creed, an examination of the mythic structure of The Plumed Serpent, and a brief forward look to Lady Chatterly's Lover, it is possible to see The Plumed Serpent as significant in the Lawrencian canon.