Sentenced to Marriage: Chained Women in Wartime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

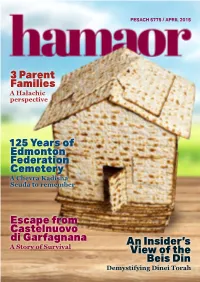

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

Should Bakeries Which Are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? a Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER

Should Bakeries Which are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? A Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER This paper was submitted as a response to the responsum written by Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz and Ms. Dvora Weisberg entitled "Rabbinic Supervision of Jewish Owned Businesses Operating on Shabbat" which was adopted by the CJLS on February 26, 1986. Should rabbis offer rabbinic supervision to bakeries which are open on Shabbat? i1 ~, '(l) l'\ (1) The food itself is indeed kosher after Shabbat, once the time required to prepare it has elapsed. 1 The halakhah is according to Rabbi Yehudah and not according to the Mishnah which is Rabbi Meir's opinion. (2) While a Jew who does not observe all the mitzvot is in some instances deemed trustworthy, this is never the case regarding someone who flagrantly disregards the laws of Shabbat, especially for personal profit. Maimonides specifically excludes such a person's trustworthiness regarding his own actions.2 Moreover in the case of n:nv 77n~ (a violator of Shabbat) Maimonides explicitly rejects his trustworthiness. 3 No support can be brought from Moshe Feinstein who concludes, "even if the proprietor closes his store on Shabbat, [since it is known to all that he does not observe Shabbat], we assume he only wants to impress other observant Jews so they will buy from him."4 Previously in the same responsum R. Feinstein emphasizes that even if the person in The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

Getting Your Get At

Getting your Get at www.gettingyourget.co.uk Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers. by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB The website at www.gettingyourget.co.uk is sponsored by Barnett Alexander Conway Ingram, Solicitors, London 1 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Dedicated to the loving memory of Sharon Faith’s late parents, Maisie and Dr Oswald Ross (zl) and Deanna Levine’s late parents, Cissy and Ellis Levine (zl) * * * * * * * * Published by Cissanell Publications PO Box 12811 London N20 8WB United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 © Sharon Faith and Deanna Levine First edition: February 2002 Second edition: July 2002 Third edition: 2003 Fourth edition: 2005 ISBN 0-9539213-1-X Fifth edition: 2006 ISBN 0-9539213-4-4 Sixth edition: 2008 ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 2 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Getting your Get Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB List of Contents Page Number Letters of endorsement. Quotes from letters of endorsement ……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements. Family Law in England, Wales and Scotland. A note for the reader seeking divorce…………. 8 A note for the lawyer …………….…….. …………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Legislation: England and Wales …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Legislation: Scotland ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 1. Who needs a Get? .……………………………………………………………………………….…………………... 14 2. What is a Get? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 3. Highlighting the difficulties ……………………………………………………………………………….………….. 15 4. Taking advice from your lawyer and others ………………………………………………………………………. -

Daat Torah (PDF)

Daat Torah Rabbi Alfred Cohen Daat Torah is a concept of supreme importance whose specific parameters remain elusive. Loosely explained, it refers to an ideology which teaches that the advice given by great Torah scholars must be followed by Jews committed to Torah observance, inasmuch as these opinions are imbued with Torah insights.1 Although the term Daat Torah is frequently invoked to buttress a given opinion or position, it is difficult to find agreement on what is actually included in the phrase. And although quite a few articles have been written about it, both pro and con, many appear to be remarkably lacking in objectivity and lax in their approach to the truth. Often they are based on secondary source and feature inflamma- tory language or an unflatttering tone; they are polemics rather than scholarship, with faulty conclusions arising from failure to check into what really was said or written by the great sages of earlier generations.2 1. Among those who have tackled the topic, see Lawrence Kaplan ("Daas Torah: A Modern Conception of Rabbinic Authority", pp. 1-60), in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, published by Jason Aronson, Inc., as part of the Orthodox Forum series which also cites numerous other sources in its footnotes; Rabbi Berel Wein, writing in the Jewish Observer, October 1994; Rabbi Avi Shafran, writing in the Jewish Observer, Dec. 1986, p.12; Jewish Observer, December 1977; Techumin VIII and XI. 2. As an example of the opinion that there either is no such thing now as Daat Torah which Jews committed to Torah are obliged to heed or, even if there is, that it has a very limited authority, see the long essay by Lawrence Kaplan in Rabbinic Authority and Personal Autonomy, cited in the previous footnote. -

Research Bulletin Series Jewish Law and Economics Game Theory in The

Research bulletin Series on Jewish Law and Economics Game Theory in the Talmud Robert J. Aumann Dedicated to the memory of Shlomo Aumann, Talmudic scholar and man of the world, killed in action near Khush-e-Dneiba, Lebanon, on the eve of the nineteenth of Sivan 5742 (June 9, 1982) Abstract A passage from the Talmud whose explanation eluded commentators for two millennia is elucidated with the aid of principles suggested by modern mathematical Theory of Games. ________________ * Institute of Mathematics, Center for rationality and Interactive Decision Theory, and Department of Economics, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem Game Theory in the Talmud1 By Robert J. Aumann l. A Bankruptcy Problem A man dies, leaving debts totaling more than his estate. How should the estate be divided among the creditors? A frequent solution in modern law is proportional division. The rationale is that each dollar of debt should be treated in the same way; one looks at dollars rather than people. Yet it is by no means obvious that this is the only equitable or reasonable system. For example, if the estate does not exceed the smallest debt, equal division among the creditors makes good sense. Any amount of debt to one person that goes beyond the entire estate might well be considered irrelevant; you cannot get more than there is. A fascinating discussion of bankruptcy occurs in the Babylonian Talmud2 (Ketubot 93a). There are three creditors; the debts are 100, 200 and 300. Three cases are considered, corresponding to estates of 100, 200 and 300. The Mishna stipulates the divisions shown in Table 1. -

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

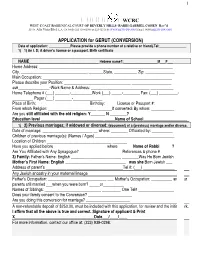

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 12 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer Jonathan Bush Columbia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Jonathan Bush, Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 259 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUSH MACRO FINAL*.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/24/17 7:22 PM Nuremberg and Beyond: Jacob Robinson, International Lawyer JONATHAN A. BUSH* Jacob Robinson (1889–1977) was one of the half dozen leading le- gal intellectuals associated with the Nuremberg trials. He was also argu- ably the only scholar-activist who was involved in almost every interna- tional criminal law and human rights battle in the two decades before and after 1945. So there is good reason for a Nuremberg symposium to include a look at his remarkable career in international law and human rights. This essay will attempt to offer that, after a prefatory word about the recent and curious turn in Nuremberg scholarship to biography, in- cluding of Robinson. -

Cincinnati Torah הרות

בס"ד • A PROJECT OF THE CINCINNATI COMMUNITY KOLLEL • CINCYKOLLEL.ORG תורה מסינסי Cincinnati Torah Vol. VI, No. XXXVIII Eikev A LESSON FROM A TIMELY HALACHA THE PARASHA RABBI YITZCHOK PREIS RABBI CHAIM HEINEMANN OUR PARASHA INCLUDES THE BIBLICAL MITZVAH human nature and how each of these mitzvahs A common question that comes up during to thank Hashem after eating a satisfying is designed to protect us from a potential hu- bein hazmanim and summer break is meal—the blessings we typically refer to as man failing. whether it is appropriate to remove one’s bentching or Birkat Hamazon. A spiritual hazard looms immediately fol- tallis katan (or tzitzis) while playing sports or The Talmud suggests that, logically, if we lowing a satisfying meal. Prior to eating, while engaging in strenuous activities that make are obligated to bless Hashem after eating, hungry, it easy to sense our dependency on one hot and sweaty. kal vachomer (all the more so), we should be our Provider. But once satisfying that hunger, While it is true that neither Biblical nor expected to recite a bracha before eating. After our attitude can shift. We run the risk of Rabbinic law obligates one to wear a all, someone who is famished is more acutely becoming self-assured, confident in our own tallis katan at all times, it has become the aware of the need for food and more appre- sustenance, and potentially dismissive of the accepted custom that every male wears a ciative that Hashem has made it available to True Source of satiation. Bentching protects tallis katan all day long. -

Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff Modest Communication Question

1 CJLS OH 74.2019α Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff Modest Communication Approved, June 19, 2019 (20‐0‐0). Voting in favor: Rabbis Pamela Barmash, Noah Bickart, Elliot Dorff, Baruch Frydman‐Kohl, Susan Grossman, Judith Hauptman, Joshua Heller, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Micah Peltz, Avram Reisner, Robert Scheinberg, David Schuck, Deborah Silver, Ariel Stofenmacher, Iscah Waldman, Ellen Wolintz Fields. Question: How can a Jew promote oneself professionally and socially without violating Jewish norms of modesty (tzi’ni’ut) in communication? Put another way, in light of the fact that in social media people actively seek affirmation (likes, shares, etc.) for their posts and the fact that some jobs even require the generation of such quantifiable affirmations, how can and should a Jew living in this social and professional environment participate in it while still observing traditional Jewish norms regarding modest speech? Answer: Introduction Now that our colleagues, Rabbis David Booth, Brukh Frydman‐Kohl, and Ashira Konisgburg have completed their rabbinic ruling on modesty in dress,1 I intend in this responsum to continue their work in a related area, modesty in communication. In a companion responsum, I will also discuss harmful communication. In this responsum in particular it is important to note at the outset that many of the norms that are discussed could be understood, on the positive end of the spectrum, as either laws obligating a particular form of behavior or, in contrast, as aspirational modes of behavior (middat hassidut), and, on the negative end of the spectrum, some will straddle the line between legally prohibited and permitted but discouraged. -

Source Sheet

Defeating the Meraglim of 2015 R' Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] Three articles Rav Soloveitchik's Approach To Zionism (2002), edited by Dr. Aviad haCohen, http://etzion.org.il/vbm/english/alei/14-02ral-zionism.htm Diaspora Religious Zionism: Some Current Reflections (2007), Orthodox Forum http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/730117 The Ideology of Hesder (1981), Tradition 19:3 http://etzion.org.il/vbm/english/archive/ral2-hes.htm A Halachic Zionism 1. Talmud, Ketuvot 111a ג' שבועות הללו למה אחת שלא יעלו ישראל בחומה ואחת שהשביע הקב"ה את ישראל שלא ימרדו באומות העולם ואחת שהשביע הקב"ה את העובדי כוכבים שלא ישתעבדו בהן בישראל יותר מדאי What is the purpose of these three oaths? That the Jews should not ascend as a wall, that the Jews should not rebel against the nations, and that the nations should not overly oppress the Jews. 2. Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Chanukah 3:2 ולא מצאו שמן טהור במקדש אלא פך אחד ולא היה בו להדליק אלא יום אחד בלבד והדליקו ממנו נרות המערכה שמונה ימים עד שכתשו זיתים והוציאו שמן טהור. And they did not find pure oil in the Mikdash, other than one jug, which contained enough oil to light for only one day. They lit the lamps from it for eight days, until they crushed olives and produced pure oil. 3. Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuvah 2:4 מדרכי התשובה להיות השב צועק תמיד לפני ד' בבכי ובתחנונים ועושה צדקה כפי כחו ומתרחק הרבה מן הדבר שחטא בו ומשנה שמו כלומר אני אחר ואיני אותו האיש שעשה אותן המעשים ומשנה מעשיו כולן לטובה.. -

ARCHIVE of AUSTRALIAN JUDAICA HOLDINGS 1983–2012 Compiled

Monograph No. 16 ISSN 0815-3850 ARCHIVE OF AUSTRALIAN JUDAICA HOLDINGS 1983–2012 Compiled by Marianne Dacy Project director Suzanne Rutland Published by the Archive of Australian Judaica, University of Sydney Library, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INDIVIDUAL COLLECTIONS - Bibliographical 1–25 Resources Name Index Collection (by shelf list) 26 Subject Index (by shelf list) 27 IIA ORGANISATIONAL ARCHIVES 28 IIB COMMUNITY ARCHIVES 39 III PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION 41 IV AUSTRALIAN YIDDISH LITERATURE 42 V SUBJECT FILES 44 VI TAPE COLLECTIONS 53 VII CURRENT PERIODICALS (JEWISH COMMUNITIES) 54 VIII CURRENT PERIODICALS (JEWISH ORGANISATIONS) 54 IX CURRENT ANNUAL REPORTS 56 X THESES AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS 57 XI EPHEMERA 59 XII PERIODICALS (ASSEMBLED) 65 XIII VIDEOS 2 INDEX OF NAMES OF INDIVIDUALS (by shelf list) COLLECTIONS (by shelf list) Shelf List) AARON, Aaron 30 PATKIN, Ben Zion 20 APPLE, Raymond Rabbi 73 PEARL, Cyril 18 ABRAHAM, Vivienne 59 PIZEM, Sam 69 BAER, Werner 25 PORUSH, Israel 54 BERG, Maurice de 16 RICH-SCHALIT, Ruby 40 BERGER, Theo 22 ROSENBLUM, Myer 52 BISCHOPSWERDER, Boaz 54 RUBINSTEIN, W. 63 BOAS, Harold 37 SCHWARTZ, Agnes 33 BRAHAM, Mark 8 SHEPPARD, Alec W. 9 CAPLAN, Leslie 29B SOLVEY, Joseph 31 CAPLAN, Sophie 29A SPITZER, Sam 65 CHER, Ivan 43 STRICKER, Beata 60 COHEN, Ilana 58 STRICKER, Henry 61 COHEN, David 35 STONE, Julius 58 CROWN, Alan 44 SYMONDS, Ken 48 DAVIS, Richard 74 TAMARI, Moshe 55 EVEN, Arie 11 WATSON, Leo 66 FABIAN, Alfred 46 YOUNG, Joy 51 FALK, Leib Aisack 14 ZBAR, Abraham 53 FEHER, Yehuda 1 FINK, Lote 80 GOLDBERG, Solomon 15 GREGORY, George 34 GUTMAN, Margaret 49 HAMMERMAN, Bernhard 28 HELFGOTT, Eva 24A HELFGOTT, Sam 24B HERTZBERG, Leopold 42 HONIG, Eliyahu 39 ISAACS, Maurice 3 JAMES, Henry 21 JOEL, Asher 62 JOSEPH, Max 2 KAIM, Ilana 58 KARPIN, Sam 4 KATZ, Dr.