Franjo / Franz / Francesco Kresnik, a Physician and Violin Maker, As Its Key Figure in a Fascist Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts

BORDERS AND CROSSINGS TRAVEL WRITING CONFERENCE Pula – Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS BORDERS AND CROSSINGS 2018 International and Multidisciplinary Conference on Travel Writing Pula-Brijuni, 13-16 September 2018 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Published by Juraj Dobrila University of Pula For the Publisher Full Professor Alfio Barbieri, Ph.D. Editor Assistant Professor Nataša Urošević, Ph.D. Proofreading Krešimir Vunić, prof. Graphic Layout Tajana Baršnik Peloza, prof. Cover illustrations Joseph Mallord William Turner, Antiquities of Pola, 1818, in: Thomas Allason, Picturesque Views of the Antiquities of Pola in Istria, London, 1819 Hugo Charlemont, Reconstruction of the Roman Villa in the Bay of Verige, 1924, National Park Brijuni ISBN 978-953-7320-88-1 CONTENTS PREFACE – WELCOME MESSAGE 4 CALL FOR PAPERS 5 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 6 ABSTRACTS 22 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS 88 GENERAL INFORMATION 100 NP BRIJUNI MAP 101 Dear colleagues, On behalf of the Organizing Committee, we are delighted to welcome all the conference participants and our guests from the partner institutions to Pula and the Brijuni Islands for the Borders and Crossings Travel Writing Conference, which isscheduled from 13th till 16th September 2018 in the Brijuni National Park. This year's conference will be a special occasion to celebrate the 20thanniversary of the ‘Borders and Crossings’ conference, which is the regular meeting of all scholars interested in the issues of travel, travel writing and tourism in a unique historic environment of Pula and the Brijuni Islands. The previous conferences were held in Derry (1998), Brest (2000), Versailles (2002), Ankara (2003), Birmingham (2004), Palermo (2006), Nuoro, Sardinia (2007), Melbourne (2008), Birmingham (2012), Liverpool (2013), Veliko Tarnovo (2014), Belfast (2015), Kielce (2016) and Aberystwyth (2017). -

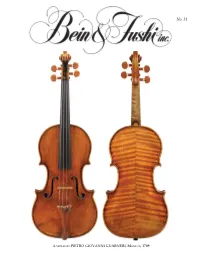

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

Irredentismo

I percorsi dell’ Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra nella Provincia di Trieste a cura di Fabio Todero Volume pubblicato con il contributo della Provincia di Trieste nell’ambito degli interventi in ambito culturale dedicati alla “Valorizzazione complessiva del territorio e dei suoi siti di pregio” e con il patrocinio del Comune di Trieste Partner di progetto: Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche e Sociali dell’Università degli Studi di Trieste Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Venezia Giulia Istituto regionale per la cultura istriana, fiumana e dalmata Associazione culturale Zenobi, Trieste © copyright 2014 by Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli Venezia Giulia Ricerche fotografiche: Michele Pupo Referenze fotografiche: Fototeca dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte del Comune di Trieste; Michele Pupo; Archivio E. Mastrociani, F. Todero; Archivio Divulgando Srl Progetto grafico: Divulgando Srl Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli Venezia Giulia Villa Primc, Salita di Gretta 38 34136 Trieste Tel. / fax +39 040 44004 www.irsml.eu e-mail: [email protected] I percorsi dell’ Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra nella Provincia di Trieste a cura di Fabio Todero 2| Indice Introduzione I percorsi dell’Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra di Fabio Todero 1. Le Rive di Fabio Todero 2. Il Palazzo della Prefettura di Diego Caltana 3. Il Colle di San Giusto di Fabio Todero 4. Il Civico Museo del Risorgimento e il Sacrario Oberdan di Fabio Todero 5. Il Liceo-ginnasio Dante Alighieri di Fabio Todero 6. I cimiteri di S. Anna e di Servola di Fabio Todero 7. -

Pristup Cjelovitom Tekstu Rada

THE IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM IN SOUTH CROATIA IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY Marija BENI PENAVA1 Marija GJURAŠI2 University of Dubrovnik, 29 Branitelja Dubrovnika, 20000 Dubrovnik, CROATIA University of Dubrovnik, 29 Branitelja Dubrovnika, 20000 Dubrovnik, CROATIA * Marija Beni Penava; E-mail: [email protected]; phone: +385 20445934 Abstract — This paper analyses, using archive records and relevant literature, the application of technological advances in transport and tourism in South Croatia in the period that preceded cruisers with thousands of passengers, mass air transport, as well as the usage of computers reservation systems and credit cards that are used in tourism industry nowadays. Technology was intensively involved in the tourism industry in the past. The impacts of technology could be seen on the connectivity by railway as well as sea, land and air traffic. In addition to the mentioned factors of communicative tourism, its receptive factors – hotel industry, catering, marketing, cultural institutions, public services etc became more dependent on technologies in the interwar period. The connection between the advances in technology and the new growing service sector of tourism in the Croatian south was a prerequisite of the coming development of mass tourism. Therefore, the human need for rest, recreation and adventure while abandoning their permanent residence achieved its purpose – enjoyment and relaxation. Peripheral parts of the Croatian south outgrew into world tourist destinations due to the progress of both transport and communication technology in the first half of the 20th century. Keywords— technology, tourism, South Croatia, 20th century 1. INTRODUCTION The Republic of Croatia is oriented towards tourism development, it is a recognized and popular destination with a clear development strategy and vision of its future in tourism. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Italian Itineraries

r n a i t l i o u i 2 2 2 G V 2 2 2 - - i i / / / l d l r 1 1 e 1 a i r n 2 2 O 2 r b e a 0 0 0 B G o 2 2 2 o z i r n e e r v S S S o a S L T T T U C C C E E E J J J O O O R R R D P P P DUO SAVERIO GABRIELLI (VIOLIN) - LORENZO BERNARDI (GUITAR) - PROJECTS 2021/2022 - TWO ITALIANS IN VIENNA - THE ITINERARIES OF ITALIAN VIRTUOSITIES D O S S I E R - G A B R I E L L I B E R N A R D I D U O Projects 2021 - 2022 TWO ITALIANS IN VIENNA Proposal 1 THE ITINERARIES OF ITALIAN VIRTUOSITIES Proposal 2 Hence the idea of the "Two Italians in Vienna" t w o project, which summarizes precisely that trend, of ITALIANS which Paganini and Giuliani are witnesses, which has seen many Italian musicians emigrate to the main i n VIENNA European capitals, including Vienna, where instrumental music was mostly enhanced. To intensify the link with Vienna, it is interesting to Vienna has been a very important hub for the investigate the role of Anton Diabelli, Austrian two most important personalities of the violin composer, pianist, and publisher, to whom and guitar: Niccolò Paganini and Mauro Beethoven himself looked with admiration (famous Giuliani. At the beginning of the nineteenth the so-called “Diabelli” Variations op. -

Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2014-15 Magyar Fantázia

What’s Next? November: Magyar Fantazia Pt. 2 – Bartok, a Microcosmos ~ On Friday and Sunday, Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2014-15 November 14 & 16, 2 pm the Rawson Duo will present the second of their Hungarian landscapes, moving beyond the streets of Budapest with its looming figure of Franz Liszt to take in Bartok’s awakening of an eastern identity in a sampling of his rural, folk-inspired miniatures along with Romanian Rhapsody No. 2 and one of his greatest chamber music masterpieces, the 1921 Sonata for violin and piano – powerfully brilliant in its color and effect, at times extroverted, intimate, and sensual to the extreme, one of their absolute favorite duos to play which has been kept under wraps for some time. December: Nordlys, music of Scandinavian composers ~ On Friday and Sunday, December 19 and 21, 2 pm the Rawson Duo will present their eighth annual Nordlys (Northern Lights) concert showcasing works by Scandinavian composers. Grieg, anyone? s e a s o n p r e m i e r e Beyond that? . as the fancy strikes (check those emails and website) Magyar Fantázia Reservations: Seating is limited and arranged through advanced paid reservation, $25 (unless otherwise noted). Contact Alan or Sandy Rawson, email [email protected] or call 379- 3449. Notice of event details, dates and times when scheduled will be sent via email or ground mail upon request. Be sure to be on the Rawsons’ mailing list. For more information, visit: www.rawsonduo.com H A N G I N G O U T A T T H E R A W S O N S (take a look around) Harold Nelson has had a lifelong passion for art, particularly photo images and collage. -

Tourism and Fascism. Tourism Development on the Eastern Italian Border 99

Petra Kavrečič: Tourism and Fascism. Tourism Development on the Eastern Italian Border 99 1.02 Petra Kavrečič* Tourism and Fascism. Tourism Development on the Eastern Italian Border** IZVLEČEK TURIZEM IN FAŠIZEM. TURISTIČNI RAZVOJ NA ITALIJANSKI VZHODNI MEJI Prispevek se osredotoča na obravnavo turističnega razvoja nekdanje italijanske province Julijske krajine (Venezia Giulia). V ospredju zanimanja je torej obdobje med obema voj- nama. Območje, ki je predmet analize, predstavlja zanimivo študijo primera, ki še ni bila deležna zadostne historične znanstvene obravnave, vsaj glede področja turističnega razvoja. Zanima me raziskovanje povezave in povezanosti med političnim režimom in nacionalnim diskurzom s turistično panogo oziroma različnimi tipologijami turistične ponudbe. Kako se je posameznim turističnim destinacijam (»starim« ali »novim«) uspelo prilagoditi novim političnim razmeram, ki so nastopile po koncu prve svetovne vojne, in kako se je turizem razvijal v okviru totalitarnega sistema, v tem primeru fašizma. Pri tem bo predstavljena različna turistična ponudba obravnavanega območja. Ključne besede: turizem, fašizem, obdobje med obema vojnama, Julijska krajina * Dr. Sc., Assistant Professor of History, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pri- morska, Titov trg 5, 6000 Koper; [email protected] ** This paper is the result of the research project “Post-Imperial Transitions and Transformations from a Local Perspective: Slovene Borderlands Between the Dual Monarchy and Nation States (1918–1923)” (J6-1801), financially supported by the Slovenian Research Agency. 100 Prispevki za novejšo zgodovino LX – 2/2020 ABSTRACT The paper explores tourism development in the Italian region of Venezia Giulia. The terri- tory under discussion represents an interesting but unexplored field of study in historiography, focusing on tourism development during the interwar period. -

Gazzetta Ufficiale Del Regno D'italia ANNO 1939 Indice Per Materia

Conto corrente con la Posta GAZZETTA FFICIAIÆ DELREGNO D'ITALIA XI ' INDICE MENSILE - 1°-30 NOVEMBRE 1939-XVIII Pubblicažioni importanti: ORDINAM.ENTO DELLO STATO CIVILE CON LA RELAZIONE MINISTERIALE A S. M. IL RE IMPERATORE Volume di 110 del pagine formato di cm. 15,5×10,5 rilegato in brosaura con sopracopertina in - semicartoncino rosso-vino. Pubblicazione n. 1981 - . , L 5 CODICE CIVILE - LIBRO I. CON LA RELAZIONE MINISTERIALE A §. M. IL RE IMPERATORE Volume di 276 pagine del formato di cm. 15,5 x 10,5 rilegato in brossura con sopracopertina in - semicartoncino rosso-vino. - Pubblicazione n. 22504is . L. 8 DISPOSIZIONI PER L'ATTUAZIONE DEL CODICE CIVILE - LIBRO I. E DISPOSIZIONI TRANSITORIE Volume di 78 pagine del formato di cm. 15,5×10,5 rilegato in brossura con sopracopertina - in semicartoncino rosso-vino. n. - Pubblicazione 2250-6is-A . L. 4 CODICE CIVILE - LIBRO DELLE SUCCESSIONI E DONAZIONI CON LA RELAZIONE MINISTERIALE A S. M. IL RE IMPERATORE Volume di 328 pagine del formato di cm. 15,5×10,5 rilegato in brossura con sopracopertina - in semicartoncino rosso-vino. Pubblicazione n. 6 - 2399-bis. L Le suddette pubb&azioni sono tutte in prima edizione stereotipa del testo ufciale Inviare le richieste alla LIBRERIA DELLO STATO - ROMA - Piazza G. Verdi, 1() (Avviso pubblicitario n. 17). - 2 - INDICE PER MATERIE Numero Numero della della Gassetta Gazzetta Abbigliamiento, Albi nazionali. I egge 16 giugno 1939-XVII, n. 1701: Norme integrative della Decreto Ministeriale 14 ottobre 1939-XVII: Norme per la te- legge 18 gennaio 1937-XV, n. 666, sulla disciplina della pro- nuta degli Albi nazionali e per gli esami di idoneità per duzione e riproduzione dei modelli di vestiario e di l'abilitazione alla funzione di esattore e collettore delle . -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Fondazione Della R.S.I

ANNO XXXII N. 2 (96) MAGGIO LUGLIO 2018 DELLA FONDAZIONE DELLA R.S.I. ISTITUTO STORICO Reg. Trib. Arezzo 5/87 21 Aprile 1987 Sped. A.P. Legge 46/2004 art. 1, comma 1 e 2 Filiale Bologna Direttore responsabile Enrico Persiani DIECI ANNI OPERATIVI DELLA FONDAZIONE DELLA RSI ISTITUTO STORICO Onlus In prima pagina di ACTA n. 66 è tà Cicogna, nella Villa Municchi di 96 celebra questo riconoscimento e scritto che l'Assemblea dei Soci del Via Pian di Maggio n. 27, oggi Via gli ultimi trenta numeri editi dalla 20 aprile 2008 scioglieva l'Associa Cicogna n. 66. Iniziava nella stessa Fondazione. Forzatamente in tre zione Culturale Istituto Storico sede l'attività della Fondazione edizioni annuali doppie, il così nato della RSI, costituita con Atto del della RSI Istituto Storico Onlus, Bimestrale ACTA è stato sempre Dott. Giuseppe Notaro di Montevar avendone la Prefettura di Arezzo ri compilato con il volontario impegno chi n. 55962 / 6255, il 22 novembre conosciuta la Personalità Giuridica il di tutti i Soci nella fedele osservanza 1986 in Terranuova Bracciolini locali 3 marzo 2005. Il presente ACTA n. delle regole statutarie dei due Enti. Nei primi 10 anni della Fondazione della RSi Istituto Storico Onlus, completati i Seminari di Studi Storici, le conferenze a Cicogna, in prevalenza intervallate da argomenti sulla Balcania e su Reparti RSI in prima linea, sono state aperte a Studi sulla Costituzione Repubblicana della RSI. Tali Studi sono culminati con 2 pubblicazioni: L'ORDINAMENTO GIURIDICO DELLA REPUBBLICA SO CIALE ITALIANA (doc.A) e FORMA DI GOVERNO E SISTEMA NORMATIVO DELLA REPUBBLICA SOCIALE ITALIANA (doc.