The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature V58 Part02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretaria Nacional De Ciencia Y Tecnología -Senacyt

CONSEJO NACIONAL DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA -CONCYT- SECRETARIA NACIONAL DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA -SENACYT- FONDO NACIONAL DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA -FONACYT- UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS QUIMICAS Y FARMACIA ESCUELA DE BIOLOGIA MUSEO DE HISTORIA NATURAL INFORME FINAL “EVALUACIÓN DE LA INCIDENCIA DE QUITRIDIOMICOSIS EN ANFIBIOS EN TRES REGIONES DE ENDEMISMO: LOS CASOS DE LOS BOSQUES NUBOSOS DE ZACAPA, BAJA VERAPAZ Y SAN MARCOS, GUATEMALA” PROYECTO FODECYT No. 70-2009 Lic. Edgar Gustavo Ruano Fajardo Investigador Principal GUATEMALA, AGOSTO DE 2012 EQUIPO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Liza Iveth García Recinos Investigador Asociado Lic. Carlos Vásquez Almazán Investigador Asociado y Coordinador Institucional Lic. Ángel Jacobo Conde Pereira Investigador Asociado Licda. Olga Alejandra Zamora Jerez Auxiliar de Laboratorio AGRADECIMIENTOS: La realización de este trabajo, ha sido posible gracias al apoyo financiero dentro del Fondo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, -FONACYT-, otorgado por La Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología -SENACYT- y al Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología - CONCYT-. OTROS AGRADECIMIENTOS Se agradece a la Escuela de Biología y Decanatura de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, específicamente a la Licda. Rosalito Barrios y Dr. Oscar Cóbar Pinto por el apoyo institucional brindado. A la Licda. Mercedes Barrios –CDC/CECON– por sus aportes y comentarios al desarrollar el proyecto, a Dr. Roberto Flores -IIQB– de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia por el préstamo de vehículo. Un especial agradecimiento a los comunitarios de la Aldea La Trinidad, Tajumulco, San Marcos, a la municipalidad de San Rafael Pie de la Cuesta, San Marcos, por permitirnos el ingreso al “Refugio del quetzal”, a la Asociación de Desarrollo Sostenible de Chilascó -ADESOCHI-, al personal del CECON en especial al personal del Biotopo para la Conservación del Quetzal “Mario Dary Rivera”, al Ing. -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

(Siphona) Geniculata (Diptera: Tachinidae), Parasite of Tipula Paludosa (Diptera) and Other Species1

199 ON THE LIFE HISTORY OF BUCENTES (SIPHONA) GENICULATA (DIPTERA: TACHINIDAE), PARASITE OF TIPULA PALUDOSA (DIPTERA) AND OTHER SPECIES1. BY JOHN RENNIE, D.Sc. AND CHRISTINA H. SUTHERLAND, M.A., B.Sc, Carnegie Scholar. (From the Laboratory of Parasitology, University of Aberdeen.) (With Plate XIV.) THE Dipterous Family, Tachinidae, comprises a very large number of species whose larvae live as parasites within other insects, particularly in their larval forms. Bucentes (Siphona) geniculata, one of the Tachinidae whose larvae are considered in the following paper, is a small ordinary looking fly, blackish in eolour and showing a somewhat greyish abdomen, with prominent abdominal bristles. The labium is long and slender, sharply geniculated about the middle of its length, and folded like a clasp knife under the head when not in use2. In a former paper (1912) one of us has recorded the occurrence of the larva of this species as a parasite in the body cavity of Tipula larvae. It is probably not confined to one host species. In one collection of Tipula larvae, a pro- portion of which yielded the parasite, the majority of the survivors, on hatching, proved to be Tipula oleracea. In most instances, however, we have found the infected insects to be T. paludosa. Since the original observation in 1912, we have found this larva regularly every year, and consequently regard it as a normal parasite of Tipula. Other observers record it from Mamestra brassicae and a related species, Siphona cristata, is reported by Roubaud (1906) to occur in Tipula gigantea. OCCURRENCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE ADULT PLY. -

Three New Species of Ctenotus (Reptilia: Sauria: Scincidae)

DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.25(2).2009.181-199 Records of the Western Australian Museum 25: 181–199 (2009). Three new species of Ctenotus (Reptilia: Sauria: Scincidae) from the Kimberley region of Western Australia, with comments on the status of Ctenotus decaneurus yampiensis Paul Horner Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, GPO Box 4646, Darwin, Northern Territory 0801, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract – Three new species of Ctenotus Storr, 1964 (Reptilia: Sauria: Scinci- dae), C. halysis sp. nov., C. mesotes sp. nov. and C. vagus sp. nov. are described. Previously confused with C. decaneurus Storr, 1970 or C. alacer Storr, 1970, C. halysis sp. nov. and C. vagus sp. nov. are members of the C. atlas species com- plex. Ctenotus mesotes sp. nov. was previously confused with C. tantillus Storr, 1975 and is a member of the C. schomburgkii species complex. The new taxa are terrestrial, occurring in woodland habitats on sandy soils in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and are distinguished from congeners by combi- nations of body patterns, mensural and meristic characteristics. Comments are provided on the taxonomic status of C. yampiensis Storr, 1975 which is considered, as in the original description, a subspecies of C. decaneurus. Re- descriptions of C. d. decaneurus and C. d. yampiensis are provided. Keywords – Ctenotus alacer, decaneurus, yampiensis, halysis, mesotes, tantillus, vagus, morphology, new species, Kimberley region, Western Australia INTRODUCTION by combinations of size, scale characteristics, body Ctenotus Storr, 1964 is the most species-rich genus colour and patterns. of scincid lizards in Australia, with almost 100 taxa recognised (Horner 2007; Wilson and Swan 2008). -

Vocalizations of Eight Species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) with Comments on Communication in the Genus

Copeia, 1990(3), pp. 631-643 Vocalizations of Eight Species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) With Comments on Communication in the Genus REGINALD B. COCROFT, ROY W. MCDIARMID, ALAN P. JASLOW AND PEDRO M. RUIZ-CARRANZA Vocalizations of frogs of the genus Atelopus include three discrete types of signals: pulsed calls, pure tone calls, and short calls. Repertoire composition is conservative across species. Repertoires of most species whose calls have been recorded contain two or three of these identifiable call types. Within a call type, details of call structure are very similar across species. This apparent lack of divergence in calls may be related to the rarity of sympatry among species of Atelopus and to the relative importance of visual communication in their social interactions. COMMUNICATION in frogs of the genus lopus by comparing the structure and behavioral Atelopus has been httle studied despite sev- context, where available, of calls of these species eral unique features of their biology that make with calls of other species reported in the lit- them an important comparative system in light erature. of the extensive work on other species of an- METHODS urans (Littlejohn, 1977; Wells, 1977; Gerhardt, 1988). First, the auditory system oí Atelopus is Calls were analyzed using a Kay Digital Sona- highly modified, and most species lack external Graph 7800, a Data 6000 Waveform Analyzer and middle ears (McDiarmid, 1971). Second, in with a model 610 plug-in digitizer, and a Mul- contrast to most anurans, species oiAtelopus are tigon Uniscan II real-time analyzer. Call fre- diurnal and often brightly colored, and visual quencies were measured from waveform and communication plays an important role in the Fourier transform analyses; pulse rates and call social behavior of at least some species (Jaslow, lengths were measured from waveform analyses 1979; Crump, 1988). -

For Review Only

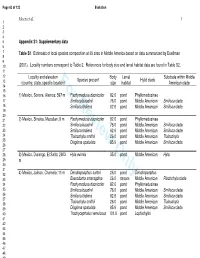

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Pseudoeurycea Naucampatepetl. the Cofre De Perote Salamander Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico. This

Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl. The Cofre de Perote salamander is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This relatively large salamander (reported to attain a total length of 150 mm) is recorded only from, “a narrow ridge extending east from Cofre de Perote and terminating [on] a small peak (Cerro Volcancillo) at the type locality,” in central Veracruz, at elevations from 2,500 to 3,000 m (Amphibian Species of the World website). Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl has been assigned to the P. bellii complex of the P. bellii group (Raffaëlli 2007) and is considered most closely related to P. gigantea, a species endemic to the La specimens and has not been seen for 20 years, despite thorough surveys in 2003 and 2004 (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org), and thus it might be extinct. The habitat at the type locality (pine-oak forest with abundant bunch grass) lies within Lower Montane Wet Forest (Wilson and Johnson 2010; IUCN Red List website [accessed 21 April 2013]). The known specimens were “found beneath the surface of roadside banks” (www.edgeofexistence.org) along the road to Las Lajas Microwave Station, 15 kilometers (by road) south of Highway 140 from Las Vigas, Veracruz (Amphibian Species of the World website). This species is terrestrial and presumed to reproduce by direct development. Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl is placed as number 89 in the top 100 Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered amphib- ians (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org). We calculated this animal’s EVS as 17, which is in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its IUCN status has been assessed as Critically Endangered. -

Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature

\M RD IV WV The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature IGzjJxjThe Official Periodical of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Volume 56, 1999 Published on behalf of the Commission by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature c/o The Natural History Museum Cromwell Road London, SW7 5BD, U.K. ISSN 0007-5167 '£' International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 56(4) December 1999 I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Notices 1 The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and its publications . 2 Addresses of members of the Commission 3 International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 4 The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature 5 Towards Stability in the Names of Animals 5 General Article Recording and registration of new scientific names: a simulation of the mechanism proposed (but not adopted) for the International Code of Zoological Nomen- clature. P. Bouchet 6 Applications Eiulendriwn arbuscula Wright, 1859 (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa): proposed conservation of the specific name. A.C. Marques & W. Vervoort 16 AUGOCHLORiNi Moure. 1943 (Insecta. Hymenoptera): proposed precedence over oxYSTOGLOSSiNi Schrottky, 1909. M.S. Engel 19 Strongylogasier Dahlbom. 1835 (Insecta. Hymenoptera): proposed conservation by the designation of Teiuhredo muhifascuim Geoffroy in Fourcroy, 1785 as the type species. S.M. Blank, A. Taeger & T. Naito 23 Solowpsis inviclu Buren, 1972 (Insecta, Hymenoptera): proposed conservation of the specific name. S.O. Shattuck. S.D. Porter & D.P. Wojcik 27 NYMPHLILINAE Duponchel, [1845] (Insecta, Lepidoptera): proposed precedence over ACENTROPiNAE Stephens. 1835. M.A. Solis 31 Hemibagnis Bleeker, 1862 (Osteichthyes, Siluriformes): proposed stability of nomenclature by the designation of a single neotype for both Bagrus neimirus Valenciennes, 1840 and B. -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Advertisement Calls, Notes on Natural History, and Distribution of Leptodactylus Chaquensis (Amphibia: Anura: Leptodactylidae) in Brasil

Advertisement calls, notes on natural history, and distribution of Leptodactylus chaquensis (Amphibia: Anura: Leptodactylidae) in Brasil W. Ronald Heyer* and Ariovaldo A. Giaretta (WRH) Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, P.O. Box 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 20013-7012, U.S.A., e-mail: [email protected]; (AAG) Universidade Federal Uberlaˆndia, 38400-902 Uberlaˆndia, Minas Gerais, Brasil, e-mail: [email protected] PROCEEDINGS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON 122(3):292–305. 2009. Advertisement calls, notes on natural history, and distribution of Leptodactylus chaquensis (Amphibia: Anura: Leptodactylidae) in Brasil W. Ronald Heyer* and Ariovaldo A. Giaretta (WRH) Amphibians and Reptiles, MRC 162, P.O. Box 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 20013-7012, U.S.A., e-mail: [email protected]; (AAG) Universidade Federal Uberlaˆndia, 38400-902 Uberlaˆndia, Minas Gerais, Brasil, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Three types of advertisement calls of Leptodactylus chaquensis from the Cerrado of Minas Gerais, Brasil are described – growls, grunts, and trills. Additional variation includes calls that start with growls andend with trills. The growl call has not been reported previously. Tadpoles are described and agree with previous descriptions. A female was found associated with tadpoles for at least 20 d. The female communicated with the tadpoles by pumping behavior and also exhibited aggressive behavior toward potential predators. The data reported herein are the first conclusive evidence that L. chaquensis occurs in the Cerrado of Minas Gerais. Other reported Brasilian records for L. chaquensis come from the southern portion of the Cerrado. Additional field work is necessary to determine whether L. chaquensis occurs in the northern Cerrado (in the states of Bahia, Distrito Federal, Maranha˜o, Para´, and Tocantins). -

Insights Into the Natural History of the Endemic Harlequin Toad, Atelopus Laetissimus Ruiz-Carranza, Ardila-Robayo, and Hernánd

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 14(1) [General Section]: 29–42 (e221). Insights into the natural history of the endemic Harlequin Toad, Atelopus laetissimus Ruiz-Carranza, Ardila-Robayo, and Hernández-Camacho, 1994 (Anura: Bufonidae), in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia 1,*Hernán D. Granda-Rodríguez, 2Andrés Camilo Montes-Correa, 3Juan David Jiménez-Bolaño, 4Alberto J. Alaniz, 5Pedro E. Cattan, and 6Patricio Hernáez 1Programa de Ingeniería Ambiental, Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad de Cundinamarca, Facatativá, COLOMBIA 2,3Grupo de Investigación en Manejo y Conservación de Fauna, Flora y Ecosistemas Estratégicos Neotropicales (MIKU), Universidad del Magdalena, Santa Marta, COLOMBIA 4Centro de Estudios en Ecología Espacial y Medio Ambiente, Ecogeografía, Santiago, CHILE 5Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, CHILE 6Centro de Estudios Marinos y Limnológicos, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, CHILE Abstract.—Atelopus laetissimus is a bufonid toad that inhabits the mountainous areas of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNSM), Colombia. This species is endemic and endangered, so information about its ecology and distribution are crucial for the conservation of this toad. Here, the relative abundance, habitat and microhabitat uses, and vocalization of A. laetissimus are described from the San Lorenzo creek in the SNSM, as well as its potential distribution in the SNSM. To this end, 447 individuals were analyzed during several sampling trips from 2010 to 2012. Against expectations, population density was signifcantly higher in the stream than in the riparian forest. Overall, A. laetissimus used seven different diurnal microhabitats, with a high preference for leaf litter substrates and rocks. -

Description of a New Reproductive Mode in Leptodactylus (Anura, Leptodactylidae), with a Review of the Reproductive Specialization Toward Terrestriality in the Genus

U'/Jeia,2002(4), pp, 1128-1133 Description of a New Reproductive Mode in Leptodactylus (Anura, Leptodactylidae), with a Review of the Reproductive Specialization toward Terrestriality in the Genus CYNTHIA P. DE A. PRADO,MASAO UETANABARO,AND Ctuo F. B. HADDAD The genus Leptodactylusprovides an example among anurans in which there is an evident tendency toward terrestrial reproduction. Herein we describe a new repro- ductive mode for the frog Leptodactyluspodicipinus, a member of the "melanonotus" group. This new reproductive mode represents one of the intermediate steps from the most aquatic to the most terrestrial modes reported in the genus. Three repro- ductive modes were previously recognized for the genus Leptodactylus.However, based on our data, and on several studies on Leptodactylusspecies that have been published since the last reviews, we propose a new classification, with the addition of two modes for the genus. T HE concept of reproductive mode in am- demonstrated by species of the "fuscus" and phibians was defined by Salthe (1969) and "marmaratus" groups. Heyer (1974) placed the Sallie and Duellman (1973) as being a combi- "marmaratus" species group in the genus Aden- nation of traits that includes oviposition site, omera.Species in the "fuscus" group have foam ovum and clutch characteristics, rate and dura- nests that are placed on land in subterranean tion of development, stage and size of hatch- chambers constructed by males; exotrophic lar- ling, and type of parental care, if any. For an- vae in advanced stages are released through urans, Duellman (1985) and Duellman and floods or rain into lentic or lotic water bodies.