2013 ELA&FN Soc Transactions Vol XXIX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL LIFE Template

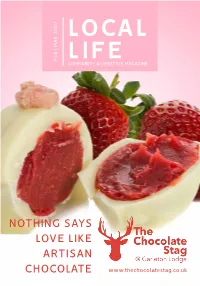

LOCAL FEB | MAR 2020 LIFECOMMUNITY & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE NOTHING SAYS LOVE LIKE ARTISAN CHOCOLATE www.thechocolatestag.co.uk CONTENTS THIS ISSUE A Sweet Tradition 4 Look what we Found! 5 relaxed living Fashion | Spring’s Nature Inspired Palette 9 Go Green at Old Smiddy 14 Interiors | Rules for Renting 18 Out of the Wood 19 Interiors | Inspired Colour 22 Food and Drink | Chocolate Chestnut Pot 24 26 Out & About elcome to our Leonardo Da Vinci: A Life in Drawing 28 first issue of the Head to the Hill 30 new decade. And for us, 31 Wthe first issue in our new home. We’re Stories in Stone | Lauderdale House excited to have moved into the Lighthouse, Dates for your Diary, Useful Numbers & Tide Times 32 in North Berwick and to be working Mind, Body & Soul | Be Free to be Who You Truly Are 34 alongside other businesses and creatives with a diverse range of skills. Mind, Body & Soul | 21 Day Self-Love Challenge 35 Yoga Poses for New Beginnings 36 The start of a new year brims with 37 excitement, new trends, new beginnings Competition | win a Personal Training Session and, of course, new year’s resolutions. Ah, 39 Health | Could I have a Dental Implant? new year’s resolutions – those things you Gardening | Ten Jobs to do in the Garden in February 42 embark upon with such gusto at the start 50 of the year, determined that this will be And Finally the year! Then, as always, life gets in the way and even with the best intentions, your resolutions do not always come to fruition. -

Dirleton Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 139 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90096), Listed Building (LB1525 Category A), Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00136) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DIRLETON CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DIRLETON CASTLE SYNOPSIS Dirleton Castle, in the heart of the pretty East Lothian village of that name, is one of Scotland's oldest masonry castles. Built around the middle of the 13th century, it remained a noble residence for four centuries. Three families resided there, and each has left its mark on the fabric – the de Vauxs (13th century – the cluster of towers at the SW corner), the Haliburtons (14th/15th century – the entrance gatehouse and east range) and the Ruthvens (16th century – the Ruthven Lodging, dovecot and gardens). The first recorded siege of Dirleton Castle was in 1298, during the Wars of Independence with England. The last occurred in 1650, following Oliver Cromwell’s invasion. However, Dirleton was primarily a residence of lordship, not a garrison stronghold, and the complex of buildings that we see today conveys clearly how the first castle was adapted to suit the changing needs and fancies of their successors. -

Scottish Borderers Between 1587 and 1625

The chasm between James VI and I’s vision of the orderly “Middle Shires” and the “wickit” Scottish Borderers between 1587 and 1625 Anna Groundwater Scottish History, University of Edinburgh L’élimination du crime le long des frontières anglaises, de pair avec un plus grand sérieux face à ce problème à partir de 1587, fait partie d’une monopolisation générale de l’utilisation de la violence et des procédés légaux par le gouvernement écossais. Au fur et à mesure que la succession de Jacques Stuart sur le trône anglais devenait vraisemblable, le contrôle des frontières s’est accéléré, et les chefs expéditionnaires des raids outre frontières y ont contribué. Aux environs de 1607, Jacques affirmait que les désordres frontaliers s’étaient transformés en une harmonie exemplaire au sein d’une nouvelle unité transfrontalière, les « Middle Shires ». Toutefois, ceci était davantage l’expression de la vision qu’avait Jacques de l’union politique de l’Écosse et de l’Angleterre, contredite par la séparation effective des organisations frontalières écossaise et anglaise, et qui a duré jusqu’en 1624. Cet article examine les transformations de la loi et du crime dans les régions frontalières, ainsi que la détérioration de la perception qu’avait le gouvernement de ces frontières. Those confining places which were the Borders of the two Kingdomes, where here- tofore much blood was shed, and many of your ancestours lost their lives; yea, that lay waste and desolate, and were habitations but for runnagates, are now become the Navell or Umbilick of both Kingdomes […] where there was nothing before […] but bloodshed, oppressions, complaints and outcries, they now live every man peaceably under his owne figgetree […] The Marches beyond and on this side Twede, are as fruitfull and as peaceable as most parts of England.1 o James declared in March 1607 to the English parliament as its members dis- Scussed the merits of union. -

1984 the Digital Conversion of This Burns Chronicle Was Sponsored by Alexandria Burns Club

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1984 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Alexandria Burns Club The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE 1984 BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 FOURTH SERIES: VOLUME IX PRICE: Paper £3.50, Cloth £4.25, (Members £2.50 and £3.00 respectively). CONTENTS George Anderson 4 From the Editor 6 Obituaries 8 Heritage James S. Adam 13 Book Reviews 14 Facts are Cheels that winna Ding J.A.M. 17 Burns Quiz 21 Afore ye go ... remember the Houses! John Riddell 22 Bi-Centenary of Kilmarnock Edition 23 Personality Parade 24 John Paul Jones and Robert Burns James Urquhart 29 Junior Chronicle 34 Mossgiel William Graham 46 Sixteen Poems of Burns Professor G. Ross Roy 48 Broughton House, Kirkcudbright 58 'Manners-Painting': Burns and Folklore Jennifer J. Connor 59 A Greetin' Roon the Warl' 63 Henryson's 'The Tail! of the Uponlandis Mous and the Burges Mous' and Burns's 'The Twa Dogs' Dietrich Strauss 64 Anecdotal Evidence R. Peel 74 Nannie's Awa' J. L. Hempstead 77 The Heart of Robert Burns Johnstone G. Patrick 78 Rob Mossgiel, Bard of Humanity Pauline E. Donnelly 81 The Lost Art of saying 'Thank you' David Blyth 89 Answers to the Quiz 91 The Burns Federation Office Bearers 92 List of Districts 97 Annual Conference Reports, 1982 101 Club Notes 114 Numerical List of Clubs on the Roll 211 Alphabetical List of Clubs on the Roll 257 The title photograph is from the Nasmyth portrait of Burns and is reproduced by courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. -

Irish and Scots

Irish and Scots. p.1-3: Irish in England. p.3: Scottish Regents and Rulers. p.4: Mary Queen of Scots. p.9: King James VI. p.11: Scots in England. p.14: Ambassadors to Scotland. p.18-23: Ambassadors from Scotland. Irish in England. Including some English officials visiting from Ireland. See ‘Prominent Elizabethans’ for Lord Deputies, Lord Lientenants, Earls of Desmond, Kildare, Ormond, Thomond, Tyrone, Lord Bourke. 1559 Bishop of Leighlin: June 23,24: at court. 1561 Shane O’Neill, leader of rebels: Aug 20: to be drawn to come to England. 1562 Shane O’Neill: New Year: arrived, escorted by Earl of Kildare; Jan 6: at court to make submission; Jan 7: described; received £1000; Feb 14: ran at the ring; March 14: asks Queen to choose him a wife; April 2: Queen’s gift of apparel; April 30: to give three pledges or hostages; May 5: Proclamation in his favour; May 26: returned to Ireland; Nov 15: insulted by the gift of apparel; has taken up arms. 1562 end: Christopher Nugent, 3rd Lord Delvin: Irish Primer for the Queen. 1563 Sir Thomas Cusack, former Lord Chancellor of Ireland: Oct 15. 1564 Sir Thomas Wroth: Dec 6: recalled by Queen. 1565 Donald McCarty More: Feb 8: summoned to England; June 24: created Earl of Clancare, and son Teig made Baron Valentia. 1565 Owen O’Sullivan: Feb 8: summoned to England: June 24: knighted. 1565 Dean of Armagh: Aug 23: sent by Shane O’Neill to the Queen. 1567 Francis Agard: July 1: at court with news of Shane O’Neill’s death. -

June & July 2018

local life free community & lifestyle magazine JUNE|JULY 2018 Caring about our coffee, our customers and our planet CONTENTS Look What we Found! 5 Fashion | Summer Suitcase Edit 11 F is for Father’s Day 12 Food and Drink | Almond and Saffron Sticky Cake 16 News for Foodies 17 SUMMER LIVING Local News 18 Finding your Inner Zen 20 Mind, Body & Soul | Your Gremlins Don’t Live in Nature 23 Dates for your Diary & Guide to Local Galas and Games 26 Fidra Fine Art Relocates to Gullane 28 LOCAL LIFE this issue It’s Show Time 32 The sun has been shining for at least three #East Lothian 34 days in a row and whilst the farmers, Your Local People | Peter and Jenny Maniam 35 greenkeepers and gardeners amongst us A Touch of the Hamptons Comes to Gullane 36 might be performing evening rain dances, the sun has everyone at Local Life HQ Let’s Talk Waffle 39 smiling and dreaming of the long hazy Interiors | Colour to Dip your Toes Into 42 days of summer. Gardening | Why Use a Garden Designer 46 This is my favourite time of year, when Tide Times & Local Numbers 54 the East Lothian landscape is at its most glorious; all in all, an inspiring setting for the fêtes and festivals that flourish across the county, from Fringe by the Sea to gala’s, festivals and games days in our local villages. We’ve pulled together a guide of this summer’s events, all you have to do is roll up! The warmer weather also encourages us out into the garden. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1987 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Jan Boydol & Brian Cumming The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE 1987 BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 FOURTH SERIES: VOLUME XII PRICE: Paper £6.50, Cl oth £10.00. (Members £4.50 and £7.00 respecti ve ly). CONTENTS D. Wilson Ogilvie 4 From the Editor 6 Obituaries 8 Burns and Loreburn Irving Miller 10 Sixth Annual Scots County Ball R. 0. Aitken 12 Burns, Jean Lorimer and James Hogg David Groves 13 Ae Paisley Prenter's Greeting T.G.11 13 The Subscribers' Edition J. A. M. 14 Gordon Mackley 15 West Sound Burns Supper Joe Campbell 16 Exotic Burns Supper William Adair 16 Henley and Henderson G. Ross Roy 17 Book Reviews 28 Sir James Crichton-Browne Donald R. Urquhart 46 Elegy Geoffrey Lund 48 The Star o' Robbie Burns Andrew E. Beattie 49 Junior Chronicle 51 Dumfries Octocentenary Celebrations David Smith 64 Frank's Golden Touch George Anderson 66 And the Rains Came! David McGregor 68 Burns and Co. David Smith 71 Burns in Glass ... James S. Adam 72 Wauchope Cairn 73 Alexander Findlater James L. Hempstead 74 Burns Alive in the USA! Robert A. Hall 86 Fraternal Greetings from Greenock Mabel A. Irving 89 Federation Centenary Celebration in Toronto Jim Hunter 90 Random Reflections from Dunedin William Brown 92 Steam Trains o the Sou-west Ronnie Crichton 93 We Made a Film about Rabbie James M. -

Consultative Draft Forres Conservation Area

Consultative Draft Forres Conservation Area Part 1: Conservation Area Appraisal Andrew PK Wright The Scottish Civic Trust Horner Maclennan McLeod & Aitken Duncan Bryden Associates June 2013 Forres Conservation Area Part 1: Conservation Area Appraisal Andrew PK Wright Chartered Architect & Heritage Consultant 16 Moy House Court Forres Moray IV36 2NZ The Scottish Civic Trust The Tobacco Merchant’s House 42 Miller Street Glasgow G1 1DT Horner Maclennan Landscape Architects No 1 Dochfour Business Centre Dochgarroch Inverness IV3 8GY McLeod & Aitken Chartered Quantity Surveyors Culbard House 22 Culbard Street Elgin IV30 1JT Duncan Bryden Associates Sheneval Tomatin Inverness IV13 7XY June 2013 Extracts of Ordnance Survey maps published in 1868 and 1905 respectively showing the centre of Forres, both © National Library of Scotland Forres Conservation Area Part 1 – Conservation Area Appraisal Contents Page no 0 Executive summary 1 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Commissioning and brief 1.2 Project team 1.3 Methodology 1.4 Credits, copyright and licensing of images 1.5 Public consultation 1.6 Acknowledgements 1.7 Date of the designation of the conservation area 1.8 Extent of the conservation area 1.9 Status of the document 2 Context 8 2.1 Topography and climate 2.2 Geology 2.3 Regional context 3 Historical background and patterns of growth 14 3.1 Pre-burghal history 3.2 The medieval burgh 3.3 From lawlessness to being a place of civilisation: the burgh from 1560 to 1750 3.4 Improvements and expansion: the burgh from 1750 to 1919 3.5 Modern developments -

Planning Application Numbers: 16/00710/PM and 16/00711/P

Planning Application Numbers: 16/00710/PM and 16/00711/P Proposed Development for 24 Dwellings at Ware Road, Dirleton The Dirleton Village Association’s Objections to the Application 24 October 2016 Background Following the statutory community consultation carried out by Muir Homes in Dirleton, the Dirleton Village Association compiled and published its comments on the proposals in a document entitled Dirleton Expects. Muir Homes responded to this document, and revised their proposals, showing them to the DVA advisers at a meeting on 2 nd August. It was explained that no approvals could be given at the meeting. The advisers were to report back to the DVA and wait for a su bse quent application before making comment. The application was made and registered on 20 th September 2016 as two submissions. The emerging LDP has now reached the ‘Proposal’ stage, and at the end of the current response period, due to end on 30 th October 2016, it will become the ‘Final’ LDP and will then be presented to the Scottish government for approval. It is therefore at an advanced stage and has already been extensively consulted upon, considered and scrutinised by ELC officers and councillors. It is described as ‘the settled view’ of the council. It contains proposals for housing developments on sites that it proposes to allocate for housing development. The application site is not included. In fact, it is shown as protected countryside under the Countryside Around Towns policy section. The following objections to the applications fall into two groups: those relating to planning matters in relation to the Proposed Local Development Plan and those which relate to the details of the proposed applications. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1591

1591 1591 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey. Jan 1,Fri New Year gifts; play, by the Queen’s Men.T Jan 1: Esther Inglis, under the name Esther Langlois, dedicated to the Queen: ‘Discours de la Foy’, written at Edinburgh. Dedication in French, with French and Latin verses to the Queen. Esther (c.1570-1624), a French refugee settled in Scotland, was a noted calligrapher and used various different scripts. She presented several works to the Queen. Her portrait, 1595, and a self- portrait, 1602, are in Elizabeth I & her People, ed. Tarnya Cooper, 178-179. January 1-March: Sir John Norris was special Ambassador to the Low Countries. Jan 3,Sun play, by the Queen’s Men.T Court news. Jan 4, Coldharbour [London], Thomas Kerry to the Earl of Shrewsbury: ‘This Christmas...Sir Michael Blount was knighted, without any fellows’. Lieutenant of the Tower. [LPL 3200/104]. Jan 5: Stationers entered: ‘A rare and due commendation of the singular virtues and government of the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, with the happy and blessed state of England, and how God hath blessed her Highness, from time to time’. Jan 6,Wed play, by the Queen’s Men. For ‘setting up of the organs’ at Richmond John Chappington was paid £13.2s8d.T Jan 10,Sun new appointment: Dr Julius Caesar, Judge of the Admiralty, ‘was sworn one of the Masters of Requests Extraordinary’.APC Jan 13: Funeral, St Peter and St Paul Church, Sheffield, of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (died 18 Nov 1590). Sheffield Burgesses ‘Paid to the Coroner for the fee of three persons that were slain with the fall of two trees that were burned down at my Lord’s funeral, the 13th of January’, 8s. -

Prestongrange House

1 Prestongrange House Sonia Baker PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. As we are enabled through this series to learn about the first millennium of the barony of Prestoungrange we can clearly see what sacrifices were made by those who worked, and how the fortunes of those who ruled rose and fell. -

Gullane Outlook Magazine (August 2019)

Outlook Gullane Parish Church August 2019 Autumn You are warmly invited to join us in the SACRAMENT OF HOLY COMMUNION Sunday 25 August 2019 9.45am and 6.30pm All welcome Dear Friends Some months ago, a good friend gave me a birthday gift. It was a book; a slim volume entitled “A Splash of Words” and written by someone of whom I had never heard, Mark Oakley. The subtitle of the work is “Believing in poetry”, a neat play on words, as its focus is both the importance of poetry and the conviction that “from its very beginnings the human intuition that the world is a gift, that it has a divine origin, and that life and love come from this same source, was explored and shared poetically.” (A Splash of Words” page xviii). In the moment of receiving, I was, of course, appreciative; grateful for my friend’s thoughtfulness and generosity. When I unwrapped it, my gratitude grew as I read the title and some of the reviews printed on the back cover. It looked like something I would enjoy. When I sat down, some weeks on, to read the first chapter, I had, once again, an increased sense of blessing as I felt immediately at home with the writing and enriched by it. The trend has continued as I have savoured the rest of the book and ordered another by the same author. I know that I will continue to dip into and benefit from Mark Oakley’s writing. Truly this has been a gift that keeps on giving.