Prestongrange House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum: University of Nottingham Letters : Copy of Father Grant’S Letter to A

Nottingham Letters Addendum: University of 170 Figure 1: Copy of Father Grant’s letter to A. M. —1st September 1751. The recipient of the letter is here identified as ‘A: M: —’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 171 Figure 2: The recipient of this letter is here identified as ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 172 Figure 3: ‘Key to Scotch Names etc.’ (NeC ¼ Newcastle of Clumber Mss.). Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 173 Figure 4: In position 91 are the initials ‘A: M: —,’ which, according to the information in NeC 2,089, corresponds to the name ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’, are on the same line as the cant name ‘Pickle’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. Notes 1 The Historians and the Last Phase of Jacobitism: From Culloden to Quiberon Bay, 1746–1759 1. Theodor Fontane, Jenseit des Tweed (Frankfurt am Main, [1860] 1989), 283. ‘The defeat of Culloden was followed by no other risings.’ 2. Sir Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History (London, [1967] 1987), 20. 3. Any subtle level of differentiation in the conclusions reached by participants of the debate must necessarily fall prey to the approximate nature of this classifica- tion. Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites. Britain and Europe, 1688–1788 (Manchester, 1994), 1–6. -

9 Decorative Pottery at Prestongrange

9 Decorative Pottery at Prestongrange Jane Bonnar This analysis is complemented by the Prestoungrange Virtual Pottery Exhibition to be found on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. -

A Singular Solace: an Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000

A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 David William Dutton BA, MTh October 2020 This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Stirling for the degree of Master of Philosophy in History. Division of History and Politics 1 Research Degree Thesis Submission Candidates should prepare their thesis in line with the code of practice. Candidates should complete and submit this form, along with a soft bound copy of their thesis for each examiner, to: Student Services Hub, 2A1 Cottrell Building, or to [email protected]. Candidate’s Full Name: DAVID WILLIAM DUTTON Student ID: 2644948 Thesis Word Count: 49,936 Maximum word limits include appendices but exclude footnotes and bibliographies. Please tick the appropriate box MPhil 50,000 words (approx. 150 pages) PhD 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by publication) 80,000 words (approx. 300 pages) PhD (by practice) 40,000 words (approx. 120 pages) Doctor of Applied Social Research 60,000 words (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Business Administration 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Education 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Midwifery / Nursing / Professional Health Studies 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Doctor of Diplomacy 60,000 (approx. 180 pages) Thesis Title: A Singular Solace: An Ecclesiastical History of Haddington, 1560-2000 Declaration I wish to submit the thesis detailed above in according with the University of Stirling research degree regulations. I declare that the thesis embodies the results of my own research and was composed by me. Where appropriate I have acknowledged the nature and extent of work carried out in collaboration with others included in the thesis. -

LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD Introduction 1 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board, 1987-1995 2 Agenda of Meetings of Lothia

LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD Introduction 1 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board, 1987-1995 2 Agenda of Meetings of Lothian Health Board Committees, 1987-1989 2A Minutes of Board, Standing Committees and Sub-Committees, 1973-1986 2B Draft Minutes of Board Meetings, 1991-2001 2C [not used] 2D Area Executive Group Minutes, 1973-1986 2E Area Executive Group Agendas and Papers, 1978-1985 2F Agenda Papers for Contracts Directorate Business Meetings, 1993-1994 2G Agenda Papers of Finance, Manpower and Establishment Committee, 1975-1979 2H Agenda papers of the Policy and Commissioning Team Finance and Corporate Services Sub- Group, 1994-1995 2I [not used] 2J Minutes and Papers of the Research Ethics Sub-Committees, 1993-1995 3 Annual Reports, 1975-2004 4 Annual Reports of Director of Public Health, 1989-2008 5 Year Books, 1977-1992 6 Internal Policy Documents and Reports, 1975-2005 7 Publications, 1960-2002 8 Administrative Papers, 1973-1994 8A Numbered Administrative Files, 1968-1993 8B Numbered Registry Files, 1970-1996 8C Unregistered Files, 1971-1997 8D Files of the Health Emergency Planning Officer, 1978-1993 9 Annual Financial Reviews, 1974-1987 10 Annual Accounts, 1976-1992 10A Requests for a major item of equipment, 1987-1990 LHB37 LOTHIAN HEALTH BOARD 11 Lothian Medical Audit Committee, 1988-1997 12 Records of the Finance Department, 1976-1997 13 Endowment Fund Accounts, 1972-2004 14 Statistical Papers, 1974-1990 15 Scottish Health Service Costs, 1975-1987 16 Focus on Health , 1982-1986 17 Lothian Health News , 1973-2001 18 Press -

1984 the Digital Conversion of This Burns Chronicle Was Sponsored by Alexandria Burns Club

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1984 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Alexandria Burns Club The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE 1984 BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 FOURTH SERIES: VOLUME IX PRICE: Paper £3.50, Cloth £4.25, (Members £2.50 and £3.00 respectively). CONTENTS George Anderson 4 From the Editor 6 Obituaries 8 Heritage James S. Adam 13 Book Reviews 14 Facts are Cheels that winna Ding J.A.M. 17 Burns Quiz 21 Afore ye go ... remember the Houses! John Riddell 22 Bi-Centenary of Kilmarnock Edition 23 Personality Parade 24 John Paul Jones and Robert Burns James Urquhart 29 Junior Chronicle 34 Mossgiel William Graham 46 Sixteen Poems of Burns Professor G. Ross Roy 48 Broughton House, Kirkcudbright 58 'Manners-Painting': Burns and Folklore Jennifer J. Connor 59 A Greetin' Roon the Warl' 63 Henryson's 'The Tail! of the Uponlandis Mous and the Burges Mous' and Burns's 'The Twa Dogs' Dietrich Strauss 64 Anecdotal Evidence R. Peel 74 Nannie's Awa' J. L. Hempstead 77 The Heart of Robert Burns Johnstone G. Patrick 78 Rob Mossgiel, Bard of Humanity Pauline E. Donnelly 81 The Lost Art of saying 'Thank you' David Blyth 89 Answers to the Quiz 91 The Burns Federation Office Bearers 92 List of Districts 97 Annual Conference Reports, 1982 101 Club Notes 114 Numerical List of Clubs on the Roll 211 Alphabetical List of Clubs on the Roll 257 The title photograph is from the Nasmyth portrait of Burns and is reproduced by courtesy of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. -

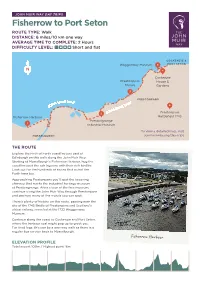

Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 Miles/10 Km One Way AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and Flat

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton ROUTE TYPE: Walk DISTANCE: 6 miles/10 km one way AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 2 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Short and flat COCKENZIE & Waggonway Museum 5 PORT SETON LONGNIDDRY 4 Cockenzie Prestonpans House & Murals Gardens 3 PRESTONPANS R W M U I AY Y H N A O W 6 J U IR N M OH 2 J Prestonpans Fisherrow Harbour Battlefield 1745 Prestongrange 1 Industrial Museum To view a detailed map, visit MUSSELBURGH joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Explore the Firth of Forth coastline just east of Edinburgh on this walk along the John Muir Way. Starting at Musselburgh’s Fisherrow Harbour, hug the coastline past the ash lagoons with their rich birdlife. Look out for the hundreds of swans that patrol the Forth here too. Approaching Prestonpans you’ll spot the towering chimney that marks the industrial heritage museum at Prestongrange. After a tour of the free museum, continue along the John Muir Way through Prestonpans and see how many of the murals you can spot. There’s plenty of history on this route, passing near the site of the 1745 Battle of Prestonpans and Scotland’s oldest railway, revealed at the 1722 Waggonway Museum. Continue along the coast to Cockenzie and Port Seton, where the harbour seal might pop up to greet you. For tired legs, this can be a one-way walk as there is a regular bus service back to Musselburgh. Fisherrow Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 100m / Highest point 16m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Fisherrow to Port Seton PLACES OF INTEREST 1 FISHERROW HARBOUR Just west of Musselburgh this harbour, built from 1850, is still used by pleasure and fishing boats. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1987 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Jan Boydol & Brian Cumming The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE 1987 BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1891 FOURTH SERIES: VOLUME XII PRICE: Paper £6.50, Cl oth £10.00. (Members £4.50 and £7.00 respecti ve ly). CONTENTS D. Wilson Ogilvie 4 From the Editor 6 Obituaries 8 Burns and Loreburn Irving Miller 10 Sixth Annual Scots County Ball R. 0. Aitken 12 Burns, Jean Lorimer and James Hogg David Groves 13 Ae Paisley Prenter's Greeting T.G.11 13 The Subscribers' Edition J. A. M. 14 Gordon Mackley 15 West Sound Burns Supper Joe Campbell 16 Exotic Burns Supper William Adair 16 Henley and Henderson G. Ross Roy 17 Book Reviews 28 Sir James Crichton-Browne Donald R. Urquhart 46 Elegy Geoffrey Lund 48 The Star o' Robbie Burns Andrew E. Beattie 49 Junior Chronicle 51 Dumfries Octocentenary Celebrations David Smith 64 Frank's Golden Touch George Anderson 66 And the Rains Came! David McGregor 68 Burns and Co. David Smith 71 Burns in Glass ... James S. Adam 72 Wauchope Cairn 73 Alexander Findlater James L. Hempstead 74 Burns Alive in the USA! Robert A. Hall 86 Fraternal Greetings from Greenock Mabel A. Irving 89 Federation Centenary Celebration in Toronto Jim Hunter 90 Random Reflections from Dunedin William Brown 92 Steam Trains o the Sou-west Ronnie Crichton 93 We Made a Film about Rabbie James M. -

Prestongrange Museum

Tell us how you feel about …. Prestongrange Museum How to have your say East Lothian Council have commissioned Simpson and Brown Architects as lead consultant to deliver a masterplan for Prestongrange Museum (PGM) to identify a vision for the sustainable future of the site and the options available to achieve this. We are interested in everyone’s views about this, whether people want no change at Prestongrange, or a significant redevelopment of the site. We also want to know how individuals and groups would like to be involved in future. There are seven main ways to have your say between now and January 2018: Respond to the public questionnaire: https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/PGMasterPlanSH Comment on the project Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/Prestongrange-Perspectives-872559646259120/ Contact the study team direct by email or ‘phone through the details below Attend one or more of the public consultation events (dates, time and venues will be posted on the Facebook page and also emailed to anyone requesting the information through responding to the questionnaire or through other means) Ask us to attend a meeting with your group or organisation. We are particularly interested to speak with groups or organisations that use the Prestongrange site at the moment or would like to use the site in future Write to us anonymously at the correspondence address below Feedback your views through your local area partnership http://www.eastlothian.gov.uk/areapartnerships How are we going to use the information? The information we are gathering will be used in drawing up the final masterplan report which is due in March 2018. -

East Lothian Life Index

East Lothian Life Index A A1 Road Dualling Tranent to Haddington 21, 18; Haddington to Dunbar 42, 16; 43, 28 A Future for the Past (Property) 27 A Meadow in Haddington (Property) 22 A Seasonal relection on beekeeping 92,37 Aberdeen Asset Management Scottish Open 92,41 Abbey Mill 34, 16; 45, 34 Aberlady 13, 13; 59, 45 Aberlady Angles 98, 72 Bay 8, 20; 35, 20 Bowling Club 84, 30 Cave 57, 30 Climate Friendly 105, 19 Curling Club 1860-2010 75, 53 Scale Model Project 57, 39 Submarines 60, 22 Village 59, 45: 60, 39 Village Kirk (The) 70, 40 Acorn Designs 10, 15 Act of Union 27, 9 Act Now to cut your Heating Costs (Property) 31 Acute Oak Decline 97,27 Adam, Robert 41, 34 Adventure Driving 1, 16 After the great War – peace in Musselburgh 73, 49 After the great War 2 75, 49 After the pips 70, 16 Aikengall 53, 28 Airfields 6, 25; 60, 33 Airships 45, 36 Alba Trees 9, 23 Alder, Ruth 50, 49 Alderston House (Homes) 29, 6 Alexander, Dr Thomas 47, 45 Allison Cargill House (Homes) 38, 40 Allotted time (Gardening) 63, 15 Allure of Haddington etc (Property), The 41 Alpacas 54, 30 Amisfield 16, 14 Amisfield Murder 60, 24 Amisfield Secret Garden 32, 10 Amisfield Lost Pineapple House 84, 27 Amisfield Park 91, 18 A night to remember – Haddington’s Blitz 78, 51 An East Lothian Icon – the Lewis Organ 80, 40 Ancient Settlements – Auldhame 97, 34 Anderson Strathearn – Graham White 99, 14 Anderson, William 22, 31 An East Lothian Gangabout 74, 30, 76, 28, 77, 28 An East Lothian Walkabout with Patrick Neill 1776-1851 75, 30 Angus, George 26, 16 Antiques Action at an -

Open Entry Form 2021 V2

Royal Musselburgh Golf Club Ltd. Open Competitions 2021 Details and Entry Form Date: Details: Tick Date: Details: Tick Entry Fee Entry Fee Entry Entry Thursday £30.00 Tuesday Junior Open – Age Max 18 £5.00 Ladies Tri-Am, Max Paying H’cap 36 13th May 2021 per Team 3rd Aug 2021 yrs. Max Playing H’cap 36 per Junior Saturday Gents Open Pairs - 2 Ball better ball £16.00 Tuesday Senior Open Texas Scramble, £40.00 15th May 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap 28 per pair 17th Aug 2021 50+ H’cap Max G28, L36 *1 per Team Tuesday Senior Open Texas Scramble, 50+ £40.00 Saturday Mixed Foursomes Open £15.00 18th May 2021 Max Playing H’cap G28, L36 *1 per Team 4th Sept2021 H’cap G28, L36 per couple Tuesday Senior Mixed Foursomes Open, 55+ £15.00 Wednesday Ladies Better Ball, Max £16.00 per 25th May 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap G28, L36 per couple 8th Sept 2021 Playing H’cap 36 Team Thursday Gents Senior Open, 55+ £15.00 per *1 - teams may be 4 Gents, 4 Ladies or a mixture 24th June 2021 Maximum Playing H’cap 28 Player Monday Ladies Greensomes, Max Playing £8.00 Entries may be made online via BRS through our website at th 28 June 2021 H’cap 36 per Player www.royalmusselburgh.co.uk No refunds will be made for cancellations Gents 18 Hole Scratch – Willie Park Saturday £15.00 per within 7 days of the competition. Putter, H’cap Max 5 and Handicap 31st July 2021 Open, Max Playing H’cap 18 Player Closing Please send completed entry form, Competition Preferred Tee Off Date cheque and SAE [or email address] to:- Ladies Tri-Am 09:30am – 14:30pm 06 May2021 Gents Open Pairs 07:00am – 14:30pm 08 May 2021 Honorary Secretary Snr Open Texas Scramble – May 07:30am – 16:00pm 11 May 2021 Royal Musselburgh Golf Club, Snr Mixed Foursomes Open 09:00am – 13:00pm 18 May 2021 Prestongrange House, Gents Senior Open 07:30am – 16:00pm 17 June 2021 PRESTONPANS, Ladies Greensomes 09:30am – 14:30pm 21 June 2021 EH32 9RP. -

2 Acheson/Morrison's Haven

2 Acheson/Morrison’s Haven What Came and Went and How? Julie Aitken PRESTOUNGRANGE UNIVERSITY PRESS http://www.prestoungrange.org FOREWORD This series of books has been specifically developed to provided an authoritative briefing to all who seek to enjoy the Industrial Heritage Museum at the old Prestongrange Colliery site. They are complemented by learning guides for educational leaders. All are available on the Internet at http://www.prestoungrange.org the Baron Court’s website. They have been sponsored by the Baron Court of Prestoungrange which my family and I re-established when I was granted access to the feudal barony in 1998. But the credit for the scholarship involved and their timeous appearance is entirely attributable to the skill with which Annette MacTavish and Jane Bonnar of the Industrial Heritage Museum service found the excellent authors involved and managed the series through from conception to benefit in use with educational groups. The Baron Court is delighted to be able to work with the Industrial Heritage Museum in this way. We thank the authors one and all for a job well done. It is one more practical contribution to the Museum’s role in helping its visitors to lead their lives today and tomorrow with a better understanding of the lives of those who went before us all. For better and for worse, we stand on their shoulders as we view and enjoy our lives today, and as we in turn craft the world of tomorrow for our children. As we are enabled through this series to learn about the first millennium of the barony of Prestoungrange we can clearly see what sacrifices were made by those who worked, and how the fortunes of those who ruled rose and fell. -

Climatevolution: Vision and Action Programme

ClimatEvolution: Vision and Action Programme Strategic Environmental Assessment Environment Report Supplementary Planning Guidance to the East Lothian Local Development Plan 2018 Published: 27/May/2020 6 Draft Environment Report: ClimatEvolution Copyright notices Mapping © Crown copyright and database rights 2020 OS licence number 100023381. You are granted a non-exclusive, royalty free, revocable licence solely to view the Licensed Data for non-commercial purposes for the period during which East Lothian Council makes it available. You are not permitted to copy, sub-license, distribute, sell or otherwise make available the Licensed Data to third parties in any form. Third party rights to enforce the terms of this licence shall be reserved to OS I-tree data Data produced using the I-Tree Suite developed by the I-Tree Cooperative has been included. The I-Tree Cooperative consist of the USDA Forest Service, Davey Tree Expert Co., National Arbor Day Foundation, Society of Municipal Arborists, International Society of Arboriculture and Casey Trees. KEY FACTS: Climate Change Resilience Zone Strategy and Action Plan The key facts relating to this PPS are set out below: Name of Responsible Authority: East Lothian Council. Title of PPS: Climate Change Resilience Zone Strategy and Action Plan (ClimatEvolution). What prompted the PPS: desire of the Council to balance the built development (housing and employment use) coming forward in the area with an attractive landscape setting, active travel and recreational offer; the desirability of addressing existing access and drainage constraints in the area and of making use of the renewable heat resource in the area. The ELC Green Network Strategy identifies action in this area as a priority.