Dirleton Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrow-Loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth Castle: Symbolism Vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’

Arrow-loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth castle: Symbolism vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’ Arrow-loops in the Great Tower of Kenilworth ground below (Fig. 7, for which I am indebted to castle: Symbolism vs Active/Passive ‘Defence’ Dr. Richard K Morris). Those on the west side have hatchet-shaped bases, a cross-slit and no in- Derek Renn ternal seats. Lunn’s Tower, at the north-east angle It is surprising how few Norman castles exhibit of the outer curtain wall, is roughly octagonal, arrow-loops (that is, tall vertical slits, cut through with shallow angle buttresses tapering into a walls, widening internally (embrasure), some- broad plinth. It has arrow-loops at three levels, times with ancillary features such as a wider and some with cross-slits and badly-cut splayed bases. higher casemate. Even if their everyday purpose Toy attributed the widening at the foot of each was to simply to admit light and air, such loops loop to later re-cutting. When were these altera- could be used profitably by archers defending the tions (if alterations they be)7 carried out, and for castle. The earliest examples surviving in Eng- what reason ? He suggested ‘in the thirteenth cen- land seem to be those (of uncommon forms) in tury, to give crossbows [... ] greater play from the square wall towers of Dover castle (1185-90), side to side’, but this must be challenged. Greater and in the walls and towers of Framlingham cas- play would need a widening of the embrasure be- tle, although there may once have been slightly hind the slit. -

LOCAL LIFE Template

LOCAL FEB | MAR 2020 LIFECOMMUNITY & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE NOTHING SAYS LOVE LIKE ARTISAN CHOCOLATE www.thechocolatestag.co.uk CONTENTS THIS ISSUE A Sweet Tradition 4 Look what we Found! 5 relaxed living Fashion | Spring’s Nature Inspired Palette 9 Go Green at Old Smiddy 14 Interiors | Rules for Renting 18 Out of the Wood 19 Interiors | Inspired Colour 22 Food and Drink | Chocolate Chestnut Pot 24 26 Out & About elcome to our Leonardo Da Vinci: A Life in Drawing 28 first issue of the Head to the Hill 30 new decade. And for us, 31 Wthe first issue in our new home. We’re Stories in Stone | Lauderdale House excited to have moved into the Lighthouse, Dates for your Diary, Useful Numbers & Tide Times 32 in North Berwick and to be working Mind, Body & Soul | Be Free to be Who You Truly Are 34 alongside other businesses and creatives with a diverse range of skills. Mind, Body & Soul | 21 Day Self-Love Challenge 35 Yoga Poses for New Beginnings 36 The start of a new year brims with 37 excitement, new trends, new beginnings Competition | win a Personal Training Session and, of course, new year’s resolutions. Ah, 39 Health | Could I have a Dental Implant? new year’s resolutions – those things you Gardening | Ten Jobs to do in the Garden in February 42 embark upon with such gusto at the start 50 of the year, determined that this will be And Finally the year! Then, as always, life gets in the way and even with the best intentions, your resolutions do not always come to fruition. -

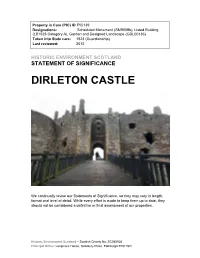

Dirleton Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 139 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90096), Listed Building (LB1525 Category A), Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00136) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DIRLETON CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DIRLETON CASTLE SYNOPSIS Dirleton Castle, in the heart of the pretty East Lothian village of that name, is one of Scotland's oldest masonry castles. Built around the middle of the 13th century, it remained a noble residence for four centuries. Three families resided there, and each has left its mark on the fabric – the de Vauxs (13th century – the cluster of towers at the SW corner), the Haliburtons (14th/15th century – the entrance gatehouse and east range) and the Ruthvens (16th century – the Ruthven Lodging, dovecot and gardens). The first recorded siege of Dirleton Castle was in 1298, during the Wars of Independence with England. The last occurred in 1650, following Oliver Cromwell’s invasion. However, Dirleton was primarily a residence of lordship, not a garrison stronghold, and the complex of buildings that we see today conveys clearly how the first castle was adapted to suit the changing needs and fancies of their successors. -

Report on the Current State- Of-Art on Protection

REPORT ON THE CURRENT STATE- OF-ART ON PROTECTION, CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION OF HISTORICAL RUINS D.T1.1.1 12/2017 Table of contents: 1. INTRODUCTION - THE SCOPE AND STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ........................................................................... 3 2. HISTORIC RUIN IN THE SCOPE OF THE CONSERVATION THEORY ........................................................................... 5 2.1 Permanent ruin as a form of securing a historic ruin .................................................................... 5 2.2 "Historic ruin" vs. "contemporary ruin" ............................................................................................ 6 2.3 Limitations characterizing historic ruins ....................................................................................... 10 2.4 Terminology of the conservation activities on damaged objects ............................................... 12 3. RESEARCH ON HISTORIC RUINS ................................................................................................................................ 14 3.1. Stocktaking measurements ............................................................................................................. 14 3.1.1. Traditional measuring techniques .............................................................................................. 17 3.1.2. Geodetic method ............................................................................................................................ 19 3.1.3. Traditional, spherical, and photography -

St Andrews Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC034 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90259) Taken into State care: 1904 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ST ANDREWS CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ST ANDREWS CASTLE SYNOPSIS St Andrews Castle was the chief residence of the bishops, and later the archbishops, of the medieval diocese of St Andrews. It served as episcopal palace, fortress and prison. -

June & July 2018

local life free community & lifestyle magazine JUNE|JULY 2018 Caring about our coffee, our customers and our planet CONTENTS Look What we Found! 5 Fashion | Summer Suitcase Edit 11 F is for Father’s Day 12 Food and Drink | Almond and Saffron Sticky Cake 16 News for Foodies 17 SUMMER LIVING Local News 18 Finding your Inner Zen 20 Mind, Body & Soul | Your Gremlins Don’t Live in Nature 23 Dates for your Diary & Guide to Local Galas and Games 26 Fidra Fine Art Relocates to Gullane 28 LOCAL LIFE this issue It’s Show Time 32 The sun has been shining for at least three #East Lothian 34 days in a row and whilst the farmers, Your Local People | Peter and Jenny Maniam 35 greenkeepers and gardeners amongst us A Touch of the Hamptons Comes to Gullane 36 might be performing evening rain dances, the sun has everyone at Local Life HQ Let’s Talk Waffle 39 smiling and dreaming of the long hazy Interiors | Colour to Dip your Toes Into 42 days of summer. Gardening | Why Use a Garden Designer 46 This is my favourite time of year, when Tide Times & Local Numbers 54 the East Lothian landscape is at its most glorious; all in all, an inspiring setting for the fêtes and festivals that flourish across the county, from Fringe by the Sea to gala’s, festivals and games days in our local villages. We’ve pulled together a guide of this summer’s events, all you have to do is roll up! The warmer weather also encourages us out into the garden. -

Planning Application Numbers: 16/00710/PM and 16/00711/P

Planning Application Numbers: 16/00710/PM and 16/00711/P Proposed Development for 24 Dwellings at Ware Road, Dirleton The Dirleton Village Association’s Objections to the Application 24 October 2016 Background Following the statutory community consultation carried out by Muir Homes in Dirleton, the Dirleton Village Association compiled and published its comments on the proposals in a document entitled Dirleton Expects. Muir Homes responded to this document, and revised their proposals, showing them to the DVA advisers at a meeting on 2 nd August. It was explained that no approvals could be given at the meeting. The advisers were to report back to the DVA and wait for a su bse quent application before making comment. The application was made and registered on 20 th September 2016 as two submissions. The emerging LDP has now reached the ‘Proposal’ stage, and at the end of the current response period, due to end on 30 th October 2016, it will become the ‘Final’ LDP and will then be presented to the Scottish government for approval. It is therefore at an advanced stage and has already been extensively consulted upon, considered and scrutinised by ELC officers and councillors. It is described as ‘the settled view’ of the council. It contains proposals for housing developments on sites that it proposes to allocate for housing development. The application site is not included. In fact, it is shown as protected countryside under the Countryside Around Towns policy section. The following objections to the applications fall into two groups: those relating to planning matters in relation to the Proposed Local Development Plan and those which relate to the details of the proposed applications. -

Gullane Outlook Magazine (August 2019)

Outlook Gullane Parish Church August 2019 Autumn You are warmly invited to join us in the SACRAMENT OF HOLY COMMUNION Sunday 25 August 2019 9.45am and 6.30pm All welcome Dear Friends Some months ago, a good friend gave me a birthday gift. It was a book; a slim volume entitled “A Splash of Words” and written by someone of whom I had never heard, Mark Oakley. The subtitle of the work is “Believing in poetry”, a neat play on words, as its focus is both the importance of poetry and the conviction that “from its very beginnings the human intuition that the world is a gift, that it has a divine origin, and that life and love come from this same source, was explored and shared poetically.” (A Splash of Words” page xviii). In the moment of receiving, I was, of course, appreciative; grateful for my friend’s thoughtfulness and generosity. When I unwrapped it, my gratitude grew as I read the title and some of the reviews printed on the back cover. It looked like something I would enjoy. When I sat down, some weeks on, to read the first chapter, I had, once again, an increased sense of blessing as I felt immediately at home with the writing and enriched by it. The trend has continued as I have savoured the rest of the book and ordered another by the same author. I know that I will continue to dip into and benefit from Mark Oakley’s writing. Truly this has been a gift that keeps on giving. -

HISTORY of the CHÂTEAU the ARTILLERY TOWER My Name Is

HISTORY OF THE CHÂTEAU 4Make your way towards the round tower, THE ARTILLERY TOWER THE PAINTINGS ROOMS LOWER CHAMBER OF THE KEEP UPPER CHAMBER OF THE KEEP the Artillery Tower, It was in the very early years of the 13th century. Bernard and enter through the postern gate. Third floor In the 11th and 12th centu- This room houses an exceptional collection of powerful and de Casnac, the powerful lord of Castelnaud, had become a Typical of this “modern” artillery were such pieces as the veuglaire ries, combatants wore a mail precise crossbows used in battle and for hunting. A collection of 14th and 15th century furniture is presented fervent supporter of the dualist religious beliefs practised by THE ARTILLERY TOWER cannons, culverins, and organs (spraying their projectiles from as shirt, which protected them very in this room of the keep. the Cathars, also known as the Albigensians. In 1214, the castle many as 12 gun barrels). effectively from sword slashes The crossbows with composite bow were armed with a spanning In the Middle Ages, furniture was very limited and followed the was seized by Simon de Montfort, a northern baron sent down to and arrows. belt with spanning hook (see the crayfish-shaped crossbow in the lords on their journeys. Displayed in the centre of the room is a culverin. crush the Cathar “heretics”. Bernard de Casnac recaptured it the The postern is a little door, often hidden, opposite the main arrowslit on the left). Each time the lord of Castelnaud moved to another residence, his following year, but it was finally burned down a few months later entrance. -

Rammed Earth Walls in Serón De Nágima Castle (Soria, Spain): Constructive Lecture

Rammed Earth Conservation – Mileto, Vegas & Cristini (eds) © 2012 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-62125-0 Rammed earth walls in Serón de Nágima castle (Soria, Spain): Constructive lecture I.J. Gil Crespo Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT: The Raya or frontier between the kingdoms of Castile and Aragón was fortified with a system of castles and walled-cities that were useful during the several conflicts that took place in the Late Medieval Age. The Serón de Nágima castle defended the communication road between the axis of the Jalón river valley, which flows into the Ebro, and Duero valley. Its uniqueness stems from the fact that it is one of the few fortifications in the area where rammed earth is the only building system used. In this paper, the castle building fundaments are exposed mainly focusing on the techniques and building proc- esses developed from the interpretation of the legible constructive signs in its walls. 1 INTRODUCTION the constructive putlog holes left in the masonry by the scaffolding we can study the systems and The Late Medieval strategy for delimitating and processes of building. The architectonical lecture defending the frontier between Castile and Aragón of these putlog holes reveals to us the auxiliary was in its systematic fortification. Ancient cas- methods and the constructive processes. tles and Muslim fortifications were repaired and This paper presents the study of the fortress of new buildings for defense were erected. The aim Serón de Nágima. This castle is, along with the of the author’s Doctoral Thesis, which gathers castle of Yanguas, the only case in which rammed from the present paper, is to know the construc- earth is the only technique used for building the tion techniques of a selection of these castles, so walls in the province of Soria. -

LOCAL LIFE Template

LOCAL JUNE | JULY 2019 JUNE | JULY LIFECOMMUNITY & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FROM EAST AFRICA TO EAST LOTHIAN CONTENTS Look what we Found! 5 THIS ISSUE relaxed living Fashion | Club Tropicana 11 Feel Good Festivals 13 From East Africa to East Lothian 14 Making Spaces 16 Butterfly Splendour 20 Interiors | The Lazy Summer Guide to a High Vibe Life 25 Summer Glamping Season in Full Swing at Harvest Moon 26 Don’t you Just love a Fête? 28 30 Dates for your Diary, Useful Numbers & Tide Times s I write we’re It’s Show Time 33 enjoying a spell of Food and Drink | Sunshine Tomatoes 34 settled and dry weather and whilst 35 Athe farmers, greenkeepers and gardeners Farming your Local Quality Produce amongst us might be performing evening Healing Herbs 36 rain dances, the rest of us are dreaming of Home Grown Passion takes you Places 38 the long hazy days of summer. 40 Mind, Body & Soul | Take a Walk in Nature This is my favourite time of year – the East Mind, Body & Soul | Nothing in this Life is Permanent 41 Lothian landscape is at its most glorious with fields of yellow and green, reminding Time for Yoga 44 me how lucky we are to live in a county full 46 Gardening | Climbing Plants for the Garden of nature’s bounty. Our cover image (taken And Finally 54 by local photographer Martin Covey) sets the scene for our cover story, From East Africa to East Lothian, telling us why it’s so important to think about the production process when we’re enjoying the fruits of farmers and producers labour. -

LOCAL LIFE Template

local life Free your community magazine FEBRUARY/MARCH 2016 Steampunk delivers the goods!....page 11 local life in this issue… Editor’s Letter 2 What’s On 4 This Issue, We’re Loving 5 Gardening – Bumper Year at Smeaton 9 Steampunk Delivers the Goods! 11 NB Gin selected by Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club 12 Food & Drink – Pecan, Maple and Brioche Pudding 14 Dear Readers A Shopper’s Guide to Spring Fashion 17 Welcome to the first issue of Local Life for 2016. The Healthy You – Back Care in the Garden 19 start of a new year brims with excitement, new trends Easter Fun at Scottish Seabird Centre 23 and the possibility of new beginnings. What’s On – Local Art Exhibitions 24 Our cover girl Mavis turns 40 this year and whilst her owners Steampunk Coffee are not ready to see her In the Spotlight – Laura Young MBE 27 retire, they are starting a new chapter in their lives with Interiors – Start Fresh this Spring 28 the launch on their online shop (page 11). A huge thanks to Rachel Seago for designing our gorgeous cover. Easter Fun 31 Archerfield Walled Garden Setting Roots Back at Home 33 Also celebrating is Laura Young, founder of the Teapot Trust, who received a MBE in the Queen’s New Year Tumbled Marble Tiles for a Chic 2016 34 Café/restaurant, deli & gallery shop Honours List in recognition of her services to chronically- The Golden Rules for Selling your Home 36 ill children in Scotland. We speak to her on page 27. Open daily from Building Wealth in Property 41 This issue features some of the key spring trends for 9.30am Useful Numbers and Weekend Tide Times 46 2016.