Consultative Draft Forres Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drainage Plan.Pdf

100 Í A9 TO INVERNESS SHEET AREA AT 1:1250 SCALE # DENOTES SHEET NUMBER NOTES 1. ONLY PLAN SHEET EXTENTS ARE SHOWN ON THE Millimetres KEY PLAN. #5.16J RET. POND ZA POND RET. Í B9154 TO DAVIOT 10 #5.16J #5.16I RET. POND XA POND RET. 0 RET. POND 9A POND RET. RET. POND YA POND RET. #5.16I #5.16H DO NOT SCALE #5.16H RET. POND 8A POND RET. #5.16J LOCH MOY INF. BASIN 7B BASIN INF. #5.16G 7A POND RET. LYNEBEG #5.16G JUNCTION MOY RAIL BRIDGE RET. POND 6A&B POND RET. FUNTACK BURN #5.16F MOY SOUTH RET. POND 5A&B POND RET. JUNCTION #5.16F DALMAGARRY #5.16E #5.16E #5.16K PROPOSED RUTHVEN LINK ROAD P01 RC GA RB 30/03/18 FIRST ISSUE Rev Drawn / Des Checked Approved Date #5.16D Description Drawing Status Suitability FINAL B Client Í A9 TO INVERNESS #5.16D #5.16B C1121 C1121 TOMATIN SOUTH Drawing Title FIGURE 5.16A JUNCTION #5.16C RIVER FINDHORN DRAINAGE PLAN SHEET 0 OF 10 TOMATIN NORTH A9 TO PERTH Scale Designed / Drawn Checked Approved Authorised A9 TO PERTH JUNCTION AS SHOWN RC GA RB SB #5.16B C1121 Î Original Size Date Date Date Date A1 30/03/18 30/03/18 30/03/18 30/03/18 Î Drawing Number Revision KEY PLAN KEY PLAN Project Originator Volume A9P12 - AMJ - HGN - P01 5HSURGXFHGE\SHUPLVVLRQRI2UGQDQFH6XUYH\RQEHKDOIRI (SCALE 1:12500) (SCALE 1:12500) +062&URZQFRS\ULJKWDQGGDWDEDVHULJKW2018. All rights X_ZZZZZ_ZZ - DR - DE - 0516 Plotted: Mar 30, 2018 - 4:43pm by: UKSMY600 UHVHUYHG2UGQDQFH6XUYH\/LFHQFHQXPEHU Location Type Role Number 100 NOTES: 1. -

Extend Time Duration of Tom Nan Clach Wind Farm from 3 to 5 Years

Agenda THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL 5.7 Item SOUTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Report PLS/030/15 19 May 2015 No 15/01404/PAN: Nanclach Ltd Tom Nan Clach Wind Farm, Glenferness, Nairn Report by Head of Planning and Building Standards Proposal of Application Notice Description : Extend time duration of Tom Nan Clach Wind Farm from 3 to 5 years. Ward : 19 - Nairn 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 To inform the Planning Applications Committee of the submission of the attached Proposal of Application Notice (PAN). 1.2 The submission of the PAN accords with the provisions of the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006 and was lodged on 13 April 2015. Members are asked to note this may form the basis of a subsequent planning application. 1.3 The following information was submitted in support of the Proposal of Application Notice: Site Location Plan Layout Plan; and Application Notice which includes: Description of Development; and Details of Proposed Consultation 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 2.1 The development comprises of: 17 wind turbines with tip-height of 110m; Access tracks; Turbine foundations and transformer plinths and enclosures; Electrical substation; Borrow pits; Permanent anemometer mast; and Temporary site construction compound. 2.2 The proposal is an application to preserve the current planning permission on the site for a 17 wind turbine development that was granted on Appeal on 14 June 2013 (09/00439/FULIN). No development has commenced. 2.3 It is unusual to receive a PAN for an application such as this, which is limited to consideration of time limits only, since most applications will have by now gone through the formal pre-application process introduced by the 2006 Act. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Moy Estate Tomatin by Inverness

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda Item 5.7 SOUTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE PLS Report No 20 AUGUST 2013 048/13 13/01180/S36 : CARBON FREE MOY LIMITED (CFML) MOY ESTATE TOMATIN BY INVERNESS Report by Head of Planning and Building Standards SUMMARY Description : Application to increase the potential generational capacity of the consented Moy Wind Farm from 41MW to 66MW. Recommendation - Raise No Objection Ward : 20 Inverness South Development Category : Section 36 Application – Electricity Act 1989. Pre-determination Hearing : Not Required Reason referred to Committee : 5 or more objections. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The application is to facilitate an increased power output from the 20 turbine wind farm project previously granted planning permission, on appeal, within Moy Estate. It offers a potential 66MW of generating capacity, an increase from the potential 41MW generating capacity associated with the approved scheme. 1.2 The application was submitted to the Scottish Government for approval under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989. Should Ministers approve the development, it will carry deemed planning permission under Section 57(2) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997. The Council is a consultee on the proposed development. Should the Council object to the development, Scottish Ministers will require to hold a Public Local Inquiry to consider the development before determining the application. 1.3 As the application is not significantly different to the earlier planning application, the supporting information relies upon the Environmental Statement (ES) prepared for the planning application. In a similar way this report seeks to focus on the key differences between the applications and to update Committee on changes to those policy/material considerations relevant to the applications to help the Committee determine its position on the consultation from the Scottish Government. -

The Glen Kyllachy Granite and Its Bearing on the Nature of the Caledonian Orogeny in Scotland

J. geol. Soc. London, Vol. 140, 1983, pp. 47-62, 4 figs., 3 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland The Glen Kyllachy Granite and its bearing on the nature of the Caledonian Orogeny in Scotland 0. van Breemen & M. A. J. Piasecki SUMMARY:The Tomatin (Findhorn) Granite in the NW GrampianHighlands has been separatedinto two distinct complexes: alate-tectonic Glen Kyllachy Granite (tectonically foliated) and a post-tectonic Findhorn Granite (flow foliated). For the Glen Kyllachy complex, Rb-Sr analyses of muscovites from the granite and from an associated suite of cross-foliated pegmatites yield an emplacement age of 443T:5 Ma. Whole-rock Rb-Sr data support field and textural evidence that the pegmatite and granite emplacement was late-tectonic to the last (F3) phase of Caledonian folding. Initial granite X7Sr/X6Srof 0.7176 supports field and geochemical evidence of derivationfrom upper crustal metasediments first metamorphosedduring the Grenville event. For the Findhorn Granite, concordant Rb-Sr and K-Ar mineral data establish an age of 413 2 5 Ma, and an initial *'SriX6Sr of c. 0.706 indicates a lower crustal and/or mantle source. Thisage and isotopiccontrast between these granites is characteristic of the whole Grampian region, in which a plutonic hiatus between c. 440 and 415Ma coincides with the peak of sedimentary accretion in the Southern Uplands, and may be explained in terms of the lack of hydrous materials passing down the associated subduction zone. Structural, metamorphic and radiometric evidence suggests (a) that the late-F3 Glen Kyllachy pegmatites are comparable with the 442 f 7 Ma old, syn-F3 pegmatites in the N Highlands- both pegmatite suites are situated in the axial zone of the metamorphic Caledonides displaced by the GreatGlen Fault; and (b) thatthe Caledonian, c. -

15. Cultural Heritage

A9 Dualling Northern Section (Dalraddy to Inverness) A9 Dualling Tomatin to Moy Stage 3 Environmental Statement 15. Cultural Heritage 15.1. Introduction 15.1.1. This chapter presents the results of the cultural heritage assessment for the Proposed Scheme. The Design Manual for Roads and Bridges (DMRB Volume 11, Section 3, Part 2: HA208/07) identifies three specific areas of interest under the overarching aspect of cultural heritage: archaeological remains, historic buildings and historic landscapes. 15.1.2. Archaeological remains consider those materials created or modified by past human activities, which includes a wide range of visible and buried artefacts, field monuments, structures and landscape features. Built heritage considers architectural, designed or other structures with a significant historical value, such as listed buildings. The historic landscape concerns perceptions that emphasise evidence of the past and its significance in shaping the present landscape. 15.1.3. Within the context of the DMRB, a cultural heritage asset is considered to be an individual archaeological site or building, a monument or group of monuments, an historic building or group of buildings and/or historic landscape. 15.1.4. In relation to archaeological remains and historic buildings the assessments have generally focussed on known sites, features, buildings and structures or sites and areas identified as having archaeological potential within the study area. 15.1.5. In relation to historic landscapes, the assessment has focussed on historic landscape types and historic landscape units within the assessment study area where social and economic activity has served to shape the landscapes in which there is a discernible awareness of their evolution. -

SB-4403-September 20

thethethe ScottishScottishScottish Banner BannerBanner 44 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 44 36 Number36 Number Number 3 11 The 11 The world’sThe world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper September May May 2013 2013 2020 Remembering Valerie Cairney US Barcodes 7 25286 844598 0 1 Australia $4.50 N.Z. $4.95 7 25286 844598 0 9 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 1 1 7 25286 844598 1 2 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 44 - Number 3 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Contact: Scottish Banner Pty Ltd. The Scottish Banner Remembering Valerie Cairney Editor PO Box 6202 to be one of her boys and it just This publication is not just our family Sean Cairney Marrickville South, NSW, 2204 happens to be I was the one to follow business, but it is her legacy to both EDITORIAL STAFF Tel:(02) 9559-6348 her in her footsteps and take a leap the international Scottish community Jim Stoddart [email protected] of faith and join the Banner many and to me. I know my mother will The National Piping Centre years ago and make a life out of being rest better knowing how many her David McVey part of the amazing international work touched and connected across Lady Fiona MacGregor Eric Bryan Scottish community. Sometimes to the world. -

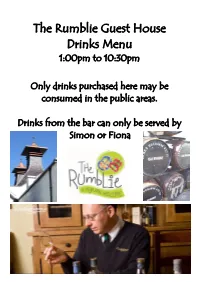

The Rumblie Guest House Drinks Menu 1:00Pm to 10:30Pm

The Rumblie Guest House Drinks Menu 1:00pm to 10:30pm Only drinks purchased here may be consumed in the public areas. Drinks from the bar can only be served by Simon or Fiona Drinks Menu– Non Alcoholic Bottle. Fentimans Lemonade 275ml £1.50 With the juice of one and a half lemons in every bottle, for real refreshment our cloudy Victorian Lemonade takes some beating. Fentimans Ginger Beer 275ml £1.50 A traditional brewed Ginger Beer with a complex taste. Made using the finest natural ginger root. Fiery and full of flavour. Fentimans Wild English Elderflower 275ml £1.50 It has a sweet floral smell with a full bodied flavour which is enhanced by the addition of pear juice during the botanical brewing process. Coca Cola £0.65 Biona Organic Orange Pressed Juice 175ml glass £0.60 Organic smooth Orange Juice is simply pressed, so more of its goodness reaches your glass. The oranges are carefully selected from organic citrus farms and freshly squeezed immediately after harvest to capture all their zesty sweetness. Biona Organic Tart Cherry Pure Juce 175ml glass £0.60 Organic tart cherry juice is made from carefully selected organic fruits, harvest fresh pressed with a rich, tart flavour. Drinks Menu—Beers Cairngorm Brewery 500ml Trade Winds 4.3% ABV £3.75 Light golden in colour with high proportion of wheat giving the beer a clean fresh taste. The mash blends together with Pearle hops and elderflower, providing a bouquet of fruit and citrus flavours.2013 Sheepshaggers Gold 4.5% ABV £3.75 A Flavoursome Blonde beer, a light golden ale, almost a continental lager style.Liquorice and caramel Scotch Ale notes in the flavour, with gentle malt and spice overtones. -

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY Planning Committee Agenda Item 5 16/10/2015

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY Planning Committee Agenda Item 5 16/10/2015 CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY Title: CONSULTATION FROM THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL (15/03286/FUL) Prepared by: KATHERINE DONNACHIE PLANNING OFFICER (DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT) DEVELOPMENT PROPOSED Erection of 13 wind turbines, including site tracks, crane hardstanding, 80m permanent anemometer mast, substation compound, temporary construction compound & provision for 3 onsite borrow pits at Tom Nan Clach Wind Farm Glenferness REFERENCE: 2015/0296/PAC APPLICANT: Nanclach Ltd RECOMMENDATION: NO OBJECTION 1 CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY Planning Committee Agenda Item 5 16/10/2015 2 CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY Planning Committee Agenda Item 5 16/10/2015 PURPOSE OF REPORT 1. The purpose of this report is to provide a consultation response to The Highland Council (who is the determining Authority for this application) on this proposed wind farm, which lies to the north of the Cairngorms National Park. The application is accompanied by an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and is categorised as a ‘major’ application. 2. The planning issues being considered in relation to this consultation are whether there are any impacts upon the qualities of the National Park. SITE DESCRIPTION AND PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT Site Description 3. The application site is located within the Highland Council administrative area at Tom Nan Clach to the north of the Cairngorms National Park. Tom Nan Clach is located some 5.5 km to the east of the A9, around 7 km to the north east of Tomatin, and some 6 km west of the B9007 Duthil to Ferness road. The closest point of the wind farm is some 5.5km to the north of the Cairngorms National Park boundary as shown in Figure 1. -

Inverness Burgh Directory Foe 1911-1912

THE Real Scotch Wincey Manufactured expressly for JOHN FORBES, Inverness, in New Stripes and Checks, also in White and all Colours, IS THE IDEAL FABRIC for Ladies' Blouses, Children's Dresses, Gent's Shirts and Pyjamas, and every kind of Day, Night and Underwear. ENDLESS IN WEAR AND POSITIVELY UNSHRINKABLE. 31 inches wide, 1/9 per yard. New Exclusive Weaves. All Fast Colours. Pattern Bunches Free on application to JOHN FORBES High Street & Inglis Street INVERNESS. SCOTTISH PROVIDENT INSTITUTION Head Office : 6 St. Andrew Sq., Edinburgh. In this SOCIETY are combined the advantages of Mutual Assurance with Moderate Premiums. Examples of Premiums for £100 at Death—With Profits- Ag-e 25 30 35 40 45 50 next Birthday During Life. £1 17 £2 2 4 £2 8 (5 &i 16 6 £3 8 2 £4 3 2 25 Payments . 2 9 2 13 11 2 19 3 3 5 11 3 15 11 4 8 8 15 Payments . 3 7 3 13 2 3 19 11 4 7 11 4 18 6 5 11 2 THE WHOLE SURPLUS is reserved exclusively for those Members who survive the period at which their Pre- miums if accumulated with ^compound interest at 4 per cent, would amount ti£jfoe^ttrfpnal assurance. PROVISION^ FOR»f THE YOUNG. A Savings Fund \|jfolic$£%»Example—An Annual Pre- mium of £10 secures t§fcs&r child age 1 next birthday an assurance commencing at age 21 of £1276 with numerous options. ENDOWMENT ASSURANCE. Special Class, with separate Fund. Eeversionary additions at the rate of £1 15s per cent, per annum were allotted at last division, and intermediate Bonuses at same rate on sums assured and existing Bonuses. -

Edinburgh Castle – Gatehouse, Inner Barrier, Old Guardhouse

Property in Care (PIC) no :PIC222 Designations: Listed Building (LB48218) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2012 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE EDINBURGH CASTLE – GATEHOUSE, INNER BARRIER, OLD GUARDHOUSE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH EDINBURGH CASTLE – GATEHOUSE, INNER BARRIER AND OLD GUARDHOUSE BRIEF DESCRIPTION The present Gatehouse, built in 1886–88, is the latest in a series of main entrances into the castle. Replacing a far simpler gate, the Victorian structure was seen as a bold intervention at the time. It is surrounded by a number of lesser constructions; the oldest, including the Inner Barrier, date from the later 17th century, and the latest, the ticket office, was constructed as recently as 2008. Archaeological investigations in the area in 1989, in advance of creating the vehicle tunnel through the castle rock, uncovered evidence for two massive Iron Age ditches in the area. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview Late 1st millennium BC: Two massive ditches are dug on the east side of the castle rock, presumably as part of a scheme to upgrade the defences of the prehistoric fort. The ditches are still serving a defensive function into the 14th century. 1649/50: The ‘forte of the castell hill’, or Spur, built in 1548 on the site of the present Esplanade, is dismantled and removed. -

The Repair and Maintenance of War Memorials ISBN 978-1-84917-115-1

3 Short Guide The Repair and Maintenance of War Memorials ISBN 978-1-84917-115-1 All images unless otherwise noted are Crown Copyright Principal Author: Jessica Snow Published by Historic Scotland, March 2013. Updated March 2014 Historic Scotland, Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh, EH9 1SH While every care has been taken in the preparation of this guide, Historic Scotland specifically exclude any liability for errors, omissions or otherwise arising from its contents and readers must satisfy as to the principles and practices described. The repair and maintenance of war memorials Contents 1. Introduction 02 2. Design and context 04 3. Recording the monument 10 4 . Stone elements 11 5. Concrete elements 22 6. Metal elements 23 7. Gilding and other finishes 29 8. Stained and decorative glass 30 9. Graffiti and vandalism 31 10. Bird control 33 11. Summary of common defects and suggested actions 34 12. Statutory consents 35 13. Adding names to war memorials 37 14. Moving memorials 38 15. Summary 39 16. Grants 40 17. Contacts 41 18. References and further reading 42 The repair and maintenance of war memorials 1. Introduction 1. Introduction Memorials of many types have been erected at various times in the past to commemorate battles and to remember the fallen from conflicts. However, war memorials became much more common following the First World War. The scale of the losses suffered in the War and the many soldiers whose fate remained unknown or uncertain left those at home with a sense of shared grief. There was hardly a parish or community in Britain where a husband, son or father had not been lost and the war memorials erected in their honour are a focal point in towns and villages throughout the country.