QR Content for “Passing the Torch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY a Long March for Suffrage

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge in1810. By her late teens, she was considered a prodigy and equal or superior in intelligence to her male friends. As an adult she hosted “Conversations” for men and women on topics that ranged from women’s rights to philosophy. She joined Ralph Waldo Emerson in editing and writing for the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial from 1840-1842. It was in this publication that she wrote an article about women’s rights titled, “The Great Lawsuit,” which she would go on to expand into a book a few years later. In 1844, she moved to NYC to write for the New York Tribune. Her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in1845. She traveled to Europe as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent, the first woman to hold such a role. She died in a shipwreck off the coast of NY in July 1850 just as she was returning to life in the U.S. Her husband and infant also perished. It was hoped that she would be a leader in the equal rights and suffrage movements but her life was tragically cut short. 02 SARAH BURKS, CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL COMMISSION December 2019 CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Harriet A. Jacobs (1813-1897) was born into slavery in Edenton, NC. She escaped her sexually abusive owner in 1835 and lived in hiding for seven years. In 1842 she escaped to the north. She eventually was able to secure freedom for her children and herself. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Suffrage Organizations Chart.Indd

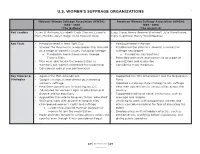

U.S. WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ORGANIZATIONS 1 National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), 1869 - 1890 1869 - 1890 “The National” “The American” Key Leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Lucy Stone, Henry Browne Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anna Howard Shaw Mary Livermore, Henry Ward Beecher Key Facts • Headquartered in New York City • Headquartered in Boston • Started The Revolution, a newspaper that focused • Established the Woman’s Journal, a successful on a range of women’s issues, including suffrage suffrage newspaper o Funded by a pro-slavery man, George o Funded by subscriptions Francis Train • Permitted both men and women to be a part of • Men were able to join the organization as organization and leadership members but women controlled the leadership • Considered more moderate • Considered radical and controversial Key Stances & • Against the 15th Amendment • Supported the 15th Amendment and the Republican Strategies • Sought a national amendment guaranteeing Party women’s suffrage • Adopted a state-by-state strategy to win suffrage • Held their conventions in Washington, D.C • Held their conventions in various cities across the • Advocated for women’s right to education and country divorce and for equal pay • Supported traditional social institutions, such as • Argued for the vote to be given to the “educated” marriage and religion • Willing to work with anyone as long as they • Unwilling to work with polygamous women and championed women’s rights and suffrage others considered radical, for fear of alienating the o Leadership allowed Mormon polygamist public women to join the organization • Employed less militant lobbying tactics, such as • Made attempts to vote in various places across the petition drives, testifying before legislatures, and country even though it was considered illegal giving public speeches © Better Days 2020 U.S. -

The Context of the Western Woman Suffrage Movement

1 The Context of the Western Woman Suffrage Movement I think civilization is coming Eastward gradually. —Theodore Roosevelt1 By the end of 1914, almost every western state and territory in the United States had enfranchised its female citizens in the greatest in- novation in participatory democracy since Reconstruction. These western successes stand in profound contrast to the East, where few women voted until after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment (1920), and to the South, where African American men were systematically disfran- chised. The regional pattern of early western victories has remained un- clear, despite many state studies, and adequate explication requires reevaluation within the contemporary political context.2 This study es- tablishes western precocity as the result of the unsettled state of regional politics, the complex nature of western race relations, broad alliances be- tween suffragists and farmer-labor-progressive reformers, and sophisti- cated activism by western women. It recognizes suffrage racism and elit- ism as major problems deeply embedded in larger cultural and political processes, and places special emphasis on the political adaptability of suf- fragists. It argues that the last generation of activists, often educated and professional women, employed modern techniques and arguments that invigorated the movement and helped meliorate class tensions. Stressing political and economic justice for women and deemphasizing prohibition persuaded increasing numbers of wary urban voters and weakened the negative influence of large cities. Thus, understanding woman suffrage in the West reintegrates this important region into national suffrage history and helps explain the ultimate success of this radical reform. 1 2 | The Context of the Movement The western victories fall clearly into three phases closely related to distinct periods of political instability and reform. -

The Woman Suffrage Debate 1865-1919

Dialectic of the Enlightenment in America: The Woman Suffrage Debate 1865-1919 Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät für Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Frau Borislava Borisova Probst, geboren Marinova Wohnadresse: Ludwig-Thoma-Str. 19, 93051 Regensburg Vorlage der Arbeit bei der Fakultät für Sprach-, Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften im Jahre 2014 Druckort: Regensburg, 2015 Erstgutachter: Herr Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat, Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik, Universität Regensburg Zweitgutachter: Frau Prof. Dr. Nassim Balestrini, Institut für Amerikanistik, Karl-Franzens- Universität Graz Dialectic of the Enlightenment in America: The Woman Suffrage Debate 1865-1919 Table of Contents: I. Introduction: I. 1. Aim of Study…………………………………………………………………..…1 I. 2. Research Situation ………………………………………………………………9 I. 2.1. Scholarly Situation on Female Suffrage ……………………………10 I. 2.2. The Enlightenment in America…………………………………..……12 I. 2.3. Dialectic of Enlightenment in America………………………….……16 I. 3. Mothodology und Sources ……………………………………………………..18 I. 3.1. Methodology………………………………………………………….18 I. 3.2. Sources………………………………………………………………30 II. Suffragist and Anti-Suffragist Pragmatics of Communication II. 1. The Progressive Era, Women and the Enlightenment…………………………33 II. 1.2. The Communication of the Suffrage Debate: The Institutionalization of the Movements…………………………….……42 II. 1.3. Organized, Public Suffrage Communication………………………………43 II. 1.4. Organized Public Anti-Suffrage Communication……………………….….67 III. Enlightenment and Inclusion: Suffrage Voices…………………………………………88 III. 1. Isabella Beecher Hooker: “The Constitutional Rights of the Women in the United States” (1888)……………90 III. 2. Carrie Chapman Catt: “Will of the People” (1910)………………………………..104 III. 3. Further Suffrage Voices………………………………………………………….…114 III. 3.1. Suffragists’ Self-understanding…………………………..……………….115 III. 3.2. Rights…………………………………………………………………..…120 III. Suffragism and Progress……………………………………………………….126 IV. -

Tennessee's Perfect 36

TENNESSEE’S TRAVELING TREASURES TEACHER’S FOR GRADES Lesson Plan 5, 9 – 12 Understanding Women’s Suffrage: Tennessee’s Perfect 36 An Educational Outreach Program of the TENNESSEE’S TRAVELING TREASURES Understanding Women’s Suffrage: Tennessee’s Perfect 36 Introduction GOAL To understand the significance of the fight for women’s suffrage and recognize the key role Tennessee played in the ratification of the 19th amendment. CONTENT The lessons in this trunk provide a detailed examination of the long fight to give women the right to vote. Students learn that there were two sides—the pro-suffrage and the anti-suffrage. Using primary source materials, students will uncover and explore argu- ments from each side, finally re-enacting the final vote that took place in Tennessee and gave women across the country the right to vote. O B J E C T I V E S • Students will define key terms in the movement for women’s right to vote. • Students will analyze primary source materials pertaining to the suffrage movement in Tennessee. PRO-SUFFRAGE ADVERTISEMENT • Students will identify the two opposing sides of this issue and consider the arguments for each side. • Students will recognize key Tennesseans who played a significant role in the women’s suffrage movement. • Students will role play a suffrage rally and re-enact the final vote of the Tennessee General Assembly granting women the right to vote. INTRODUCTION Your students will go on a journey back in time to the hot summer of 1920. The city is Nashville, and the places are the Hermitage Hotel and the Tennessee State Capitol. -

27 Fast Facts About the 19Th Amendment Breanna Mccann

27 Fast Facts About the 19th Amendment Breanna McCann The Amendment 1. The 19th Amendment does not directly mention women. Instead, it says: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” 2. The 19th Amendment was officially added to the United States constitution on August 26, 1920. 3. The 19th Amendment is also called the Anthony Amendment, named for Susan B. Anthony. 4. The first attempt at a universal suffrage amendment in Congress came in 1868, but gained no traction. The next attempt came in 1878 from California Senator Aaron A. Sargent, who introduced a bill drafted by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stan- ton. While his bill was rejected, it was introduced every year for the following forty- one years. Eventually, in 1919, Congress approved the exact text of Sargent’s original bill and it was ratified by three-fourths of states in 1920. 5. President Woodrow Wilson tried to pass a national suffrage act in 1918 in the midst of World War I. He endorsed what would later become the 19th Amendment, and one day after doing so, the House passed the measure. Wilson addressed the Senate personally, appealing to the fact that women were also actively participating in the war effort, but it failed in the Senate by two votes. A few months later, Congress attempted to pass the act again, but failed by one vote in the Senate. Early Voting Rights 6. Unmarried women were allowed to vote in New Jersey from 1797 to 1807. -

Background Guide

The National American Woman Suffrage Association 1890 (NAWSA) MUNUC 33 ONLINE1 The National American Woman Suffrage Association 1890 (NAWSA)| MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ A NOTE ON INTERSECTIONALITY FROM THE DAIS………...……….………3 CHAIR LETTERS………………………….….…………………..…….…….....…5 COMMITTEE STRUCTURE.……………..………………………………………..9 TOPIC A: ORGANIZING THE WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT……….14 Statement of the Problem……………….……………..………….…14 History of the Problem………………………………………………….26 Roster……………………………………………………………………..30 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..66 2 The National American Woman Suffrage Association 1890 (NAWSA)| MUNUC 33 Online A NOTE ON INTERSECTIONALITY FROM THE DAIS ____________________________________________________ Dear Delegates, Welcome to the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association - where you will spend your weekend writing and voting on policy that will advance gender equality and grant women the rights that they deserve. We hope this committee will provoke conversations, creativity, and a hard (and even critical) look at the movement that led to the enfranchisement of the largest group of voters at a single time. Our goal with running this committee is to teach you about how to organize and run a political movement. However, we also want you to understand and critique how political movements have worked in the past. In order to do this, we must confront both the parts of our history that are commendable and inspiring, as well as the parts of our history in which people were discriminatory or acted in a manner that we would not support today. The history we will be discussing is not faultless, and deals with racist, antisemitic, and homophobic actors both outside and within the suffrage movement. Some of you have been assigned characters who hold problematic, prejudiced beliefs. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K. -

Suffrage Centennial Patch Program

The Fifth Star Washington State and Women’s Suffrage TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ………………………………………….…….... 2 Background ………………………………………………..... 3 Suffrage: What’s the Big Deal? .………………...……….. 4 Women in the West Lead the Way ………………...…….. 5 Washington Women and the Vote ……………...……….. 6 An Incomplete Victory ……………...……………………... 8 Washington State Voting Today …...……………………. 11 Additional Resources and Activities ......………………. 12 Glossary ………………………………………….…...…….. 15 The Fifth Star Washington State and Women’s Suffrage Introduction Welcome to Girl Scouts of Western Washington’s Suffrage Centennial Patch Program! Developed in partnership with the Washington State History Museum, this program focuses on the women’s suffrage movement in Washington State and the rest of the USA. Why now? 2020 is the 100th anniversary of the passage and ratification of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, which granted women the right to vote. The 19th Amendment states: As you explore this patch program, you will Discover the history of the women’s “The right of citizens of the United suffrage movement and how Washington States to vote shall not be denied or contributed to the process that led to the abridged by the United States or by any 19th Amendment. You will Connect what State on account of sex.” you learn about women suffragists to current Women suffragists famously fought for this issues around voting, and to the role you right at both national and state levels—but play as a future voter. And, you will Take what is less known is Washington State’s Action by attending an event sponsored by role in the process. the Washington State History Museum virtually or in-person or using the information The patch for this program is modeled after in the Additional Resources section of this the flag of the National Women’s Party. -

“A Religious Recognition of Equality”: Liberal Spirituality and the Marriage Question in America, 1835–1850

religions Article “A Religious Recognition of Equality”: Liberal Spirituality and the Marriage Question in America, 1835–1850 Gregory Garvey Department of English, The College at Brockport, State University of New York, Brockport, NY 14420, USA; [email protected] Received: 16 July 2017; Accepted: 10 August 2017; Published: 8 September 2017 Abstract: Studying texts by Lydia Maria Child, Sarah Grimke, and Margaret Fuller, this article seeks to recover the early phases of a dialogue that moved marriage away from an institution grounded in ideas of unification and toward a concept of marriage grounded in liberal ideas about equality. It seeks to situate the “marriage question” within both the rhetoric of American antebellum reform and of liberal religious thought. Rather than concluding that these early texts facilitated a movement toward a contractarian ideal of marriage this article concludes that Child, Grimke, and Fuller, sought to discredit unification as an organizing idea for marriage and replace it with a definition that placed a spiritual commitment to equality between the partners as the animating core of the idea of marriage. Keywords: Transcendentalism; marriage reform; liberalism; Margaret Fuller; Lydia Maria Child; Sarah Grimke Questions about marriage reform began to accelerate onto reformers’ agendas after Lydia Maria Child and Sarah Grimke published texts of women’s history in the 1830s. Serving both religious and civil functions, the marriage tie was at the very center of adult life for the vast majority of Americans. But marriage was also profoundly anti-egalitarian, demanding sacrifices for women that contradicted basic assumptions about individual rights that by the mid-nineteenth century had transformed political, economic, and religious life. -

Dedication Planned for New National Suffrage Memorial

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month NATIONAL WOMEN'S HISTORY ALLIANCE Women Win the Vote Before1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 1920 & Beyond You're Invited! Celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote Learn What’s Happening in Your State and Online HROUGHOUT 2020, Americans will celebrate the Tcentennial of the extension of the right to vote to women. When Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919, and 36 states ratified it by August 1920, women’s right to vote was enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. Now there are local, state and national centennial celebrations in the works including shows and © Trevor Stamp © Trevor parades, parties and plays, films The Women’s Suffrage Centennial float in the Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, was seen by millions on January 1, 2020. On the float were the and performers, teas and more. descendants of suffragists including Ida B. Wells, Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Ten rows of Learn more, get involved, enjoy the ten women in white followed, waving to the crowd. Trevor Stamp photo. activities, and recognize as never before that women’s hard fought Dedication Planned for New achievements are an important part of American history. National Suffrage Memorial HE TURNING POINT Suffra- were jailed over 100 years ago. This gist Memorial, a permanent marked a critical turning point in suffrage Inside This Issue: tribute to the American women’s history. Great Resources T © Robert Beach suffrage movement, will be unveiled on Spread over an acre, the park-like A rendering of the Memorial August 26, 2020 in Lorton, Virginia.