Vestiges of Tsimshianic and Other Penutian in Bella Coola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Report No. 70

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 70 1968 FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Technical Reports FRE Technical Reports are research documents that are of sufficient importance to be preserved, but which for some reason are not aopropriate for scientific pUblication. No restriction is 91aced on subject matter and the series should reflect the broad research interests of FRB. These Reports can be cited in pUblications, but care should be taken to indicate their manuscript status. Some of the material in these Reports will eventually aopear in scientific pUblication. Inquiries concerning any particular Report should be directed to the issuing FRS establishment which is indicated on the title page. FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD DF CANADA TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 70 Some Oceanographic Features of the Waters of the Central British Columbia Coast by A.J. Dodimead and R.H. Herlinveaux FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA Biological Station, Nanaimo, B. C. Paci fie Oceanographic Group July 1%6 OONInlTS Page I. INTHOOOCTION II. OCEANOGRAPHIC PlDGRAM, pooa;OORES AND FACILITIES I. Program and procedures, 1963 2. Program and procedures, 1964 2 3. Program and procedures, 1965 3 4 III. GENERAL CHARACICRISTICS OF THE REGION I. Physical characteristics (a) Burke Channel 4 (b) Dean Channel 4 (e) Fi sher Channel and Fitz Hugh Sound 5 2. Climatological features 5 (aJ PrectpitaUon 5 (b) Air temperature 5 (e) Winds 6 (d) Runoff 6 3. Tides 6 4. Oceanographic characteristics 7 7 (a) Burke and Labouchere Channels (i) Upper regime 8 8 (a) Salinity and temperature 8 (b) OJrrents 11 North Bentinck Arm 12 Junction of North and South Bentinck Arms 13 Labouchere Channel 14 (ii) Middle regime 14 (aJ Salinity and temperature (b) OJrrents 14 (iii) Lower regime 14 (aJ 15 Salinity and temperature 15 (bJ OJrrents 15 (bJ Fitz Hugh Sound 16 (a) Salinlty and temperature (bJ CUrrents 16 (e) Nalau Passage 17 (dJ Fi sher Channel 17 18 IV. -

Eulachon Past and Present

Eulachon past and present by Megan Felicity Moody B.Sc., The University of Victoria, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Resource Management and Environmental Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2008 © Megan Felicity Moody, 2008 Abstract The eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus), a small anadromous smelt (Family Osmeridae) found only along the Northwest Pacific Coast, is poorly understood. Many spawning populations have suffered declines but as their historic status is relatively unknown and the fisheries poorly documented, it is difficult to study the contributing factors. This thesis provides a survey of eulachon fisheries throughout its geographical range and three analyses aimed at improving our understanding of past and present fisheries, coast-wide abundance status, and the factors which may be impacting these populations. An in-depth view of the Nuxalk Nation eulachon fishery on the Bella Coola River, Central Coast, BC, is provided. The majority of catches were used for making eulachon grease, a food item produced by First Nations by fermenting, then cooking the fish to release the grease. Catch statistics were kept yearly from 1945-1989 but have since, rarely been recorded. Using traditional and local ecological knowledge, catches were reconstructed based on estimated annual grease production. Run size trends were also created using local Fisheries Officers and Nuxalk interview comments. A fuzzy logic expert system was designed to estimate the relative abundance of fifteen eulachon systems. The expert system uses catch data to determine the exploitation status of a fishery and combines it with other data sources (e.g., CPUE) to estimate an abundance status index. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

1 the Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University

1 The Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University of Victoria, March 2010 Abstract This article offers an overview of the phonological typology and analysis of the Wakashan languages, namely Haisla, Heiltsukvla (Heiltsuk, Bella Bella), Oowekyala, Kwak’wala (Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), Ditidaht (Nitinaht), and Makah. Like other languages of the Northwest Coast of North America, these have many consonants, including several laterals, front and back dorsals, few labials, contrastive glottalization and lip rounding, and a glottal stop with similar distribution to other consonants. Consonant-vowel sequences are characterized by large obstruent clusters, and no hiatus. Of theoretical interest at the segmental level are consonant mutations, positional neutralizations of laryngeal features, vowel-glide alternations, glottalized vowels and glottalized voiced plosives, and historical loss of nasal consonants. Also addressed here are aspects of these languages’ rich prosodic morphology, such as patterns of reduplication and templatic stem modifications, the distribution of Northern Wakashan schwa, alternations in Southern Wakashan vowel length and presence, and the syllabification of all-obstruent words. 1. Introduction The Wakashan language are spoken in what are now British Columbia, Canada, and Washington State, USA. The family comprises a northern branch—Haisla, Heiltsukvla, Oowekyala, and Kwa kwala—and̓ a southern branch—Nuu-chah-nulth, Ditidaht, and Makah— that diverge significantly from each other, but are internally very similar. They are endangered, being spoken natively by about 350 people, out of ethnic populations of about 23,000 whose main language is English. At the same time, most are undergoing active revitalization, with about 1,000 semi-speakers and learners ( First Peoples’ Language Map ). -

Burke. Channel

~.. ~. HSHtRI tS atSu~R&' " . BGA'R~ ~f Cl~llA . .~ ~. - . ' ~ . B\OtOG\b~t ,Sl~l\Q~, .. , - '-. '.'· Sf. Jn1\tiJs.M£WfnU:Rnl~ND .., " ).0 '.;; I" . .' -... ... -.. - . IJI8:8 •••_$ _R_ . 8~~B~ (;P .·' BOA •• ," ' OF" CA -:N ' A:P&-~ " . :- ', ..~:ANJ1SCRIPT REP'O~T . SEItIES ,No. 976 .. .. " • j. _ ' - - . ' • I _I, ' . [ , '<" . ~ .. r, . Drift Card Beiea8e.8 ~ ~n, d .ReeQverielf . , .. , ... ..... • ' -' .0 >' In . '. , -,. 'Burke . Channel - .- \ . i j' , " >.- British ,Columbia, 1 1967 .. ,. 0 • b1 " ~"" 'It • ' .J 1t~1I~ ', Herlinveaq~ . .- , ~. :" . - , ", .BlQ1o.gical S-tat;on, NJlIi.tmo, B.C.; - .. i?~cifl~Qceanogr~phic Group ' . - , ' , ,~ ."~. March 1968 FISHERIES RE8EAR~B BOARD OF ~ANADA MANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 970 Drift Card Releases and Recoveries • In Burke Channel British Columbia, 1967 by R. H. Herlinveaux Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C. Pacific Oceanographic Group March 1968 Programmed by The Canadian Committee on Oceanography Drift Card Releases and Recoveries in Burke Channel, British Columbi.a, 1967 by E..H. Herlinveaux INTRODUCTION Burke Channel is the main migratory route of the pink salmon moving into and out of the Bella Coola River system (Figure 1). On their way to the sea, the pink salmon spend approximately twq months (mid~April to mid-June) in the system, during which time a significant and variable mortality occurs. The mortality must be associated partly with environmental factors. among which water movements are considered to be most significant. Water movements may either directly tiansport the fish, or, by altering the salinity distribution, and! or by concentrating or dispersing food organisms, modify their travel. Furthermore , variation in water movements may change the nutrient supply, which in turn will alter production of food necessary for growth and survivaL An extensive 5=year study of the l!spring Qceanographic conditionsl! in the system was terminated in 1967. -

7"'" Eyak Tlingit/1\ Dialects

301 302 THE ATHABASCAN COMPONENT OF NUXALK so be shown that the Nuxalk-Athabascan connection underlies certain phonological traits and developments in Nuxalk that are quite unique in Salish. Considering Hank Nater Red Earth Creek, Alberta the typological distance between Salish and Athabascan in general, we infer that Athabascan linguistic pressure has been more penetrating in Nuxalk than in other Canada TOGlXO Salish;2 the likelihood that the origin of the Nuxalk-Athabascan interrelation antedates the development of the Nuxalk-Wakash Sprachbund is an indication that O. Introduction. Obvious lexical similarities between Nuxalk (Bella Coola, at least a section of the Nuxalk population has ancestral ties with the Interior Salish) and Upper North Wakash have been described on previous occasions (Nater Salish (which is corroborated by the fact that the Salish portion of the Nuxalk 1974, 1977, 1984; Nater and Rath 1987; Newman 1973). I also reported that a few lexicon links Nuxalk with both Coast and Interior Salish, cf. Nater 1984: XVII). Nuxalk words appear to be of Athabascan origin, and it is the latter portion of In this paper, the circumflex (as in lei le'l I§/) is used instead of the hachek the Nuxalk lexicon that we shall examine here in more detail than before. Note to transcribe apico-alveolars; in Iii and Iii, the superscript dot replaces the that, while I had presumed that traces of Athabascan vocabulary in Nuxalk were subscript dot, and Igl = IG/. References are abbreviated as follows: C = Cook largely attributable to interaction with speakers of contemporary neighboring 1983; CD = Carrier Dictionary Committee 1974; K70 = Kuipers 1970, K74 = Kuipers Athabascan languages (Carrier, Chilcotin), further research has revealed that 1974, K82 = Kuipers 1982, K89 = Kuipers 1989; KL = Krauss and Leer 1981; L = most such borrowings are older than hitherto alleged; in addition, the number of Leer 1979; LR = Lincoln and Rath 1986; MI = Morice 1932 (vol. -

UBCWPL University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics

UBCWPL University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics -Papers for ICSNL 53- The Fifty-Third International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages Edited by: Marianne Huijsmans, Roger Lo, Daniel Reisinger, and Oksana Tkachman August 2018 Volume 47 -Papers for ICSNL 53- The Fifty-Third International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages Bellingham,WA August 10–11th, 2018 Hosted by: Whatcom Museum, WA Edited by: Marianne Huijsmans, Roger Lo, Daniel Reisinger, and Oksana Tkachman The University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 47 July 2018 UBCWPL is published by the graduate students of the University of British Columbia. We feature current research on language and linguistics by students and faculty of the department, and we are the regular publishers of two conference proceedings: the Workshop on Structure and Constituency in Languages of the Americas (WSCLA) and the International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages (ICSNL). If you have any comments or suggestions, or would like to place orders, please contact : UBCWPL Editors Department of Linguistics Totem Field Studios 2613 West Mall V6T 1Z2 Tel: 604 822 8948 Fax 604 822 9687 E-mail: <[email protected]> Since articles in UBCWPL are works in progress, their publication elsewhere is not precluded. All rights remain with the authors. i Cover artwork by Lester Ned Jr. Contact: Ancestral Native Art Creations 10704 #9 Highway Compt. 376 Rosedale, BC V0X 1X0 Phone: (604) 793-5306 Fax: (604) 794-3217 Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-88865-301-7 ii Table of Contents PREFACE ............................................................................ v JOHN DAVIS ................................................................... 1–8 Expressing future certainty in Comox MARIANNE HUIJSMANS AND DANIEL REISINGER ........ -

Segmental Phonology Darin Howe University of Calgary

SEGMENTAL PHONOLOGY DARIN HOWE HOWED UCALGARY.CA UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY DARIN HOWE, 2003 ii Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................................................IV INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET CHART.................................................................................................. V 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................................................1 2. INTRASEGMENTAL PHONOLOGY ..................................................................................................................4 2.1. PHONEME INVENTORIES AND FEATURES.......................................................................................................... 4 2.2. ARTICULATOR-FREE FEATURES .....................................................................................................................12 2.2.1. Major class features .................................................................................................................................................12 2.2.1.1. [±consonantal]...........................................................................................................................................12 2.2.1.2. [±sonorant].................................................................................................................................................22 2.2.2. Other articulator-free features..............................................................................................................................27 -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT TITEL DER DIPLOMARBEIT “The Politics of Storytelling”: Reflections on Native Activism and the Quest for Identity in First Nations Literature: Jeannette Armstrong’s Slash, Thomas King’s Medicine River, and Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach. VERFASSERIN Agnes Zinöcker ANGESTREBTER AKADEMISCHER GRAD Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, im Mai 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuer: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz Acknowledgements To begin with, I owe a debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Waldemar Zacharasiewicz. He supported me in stressful times and patiently helped me to sort out my ideas about and reflections on Canadian literature. He introducing me to the vast field of First Nations literature, shared his insights and provided me with his advice and encouragements to develop the skills necessary for literary analysis. I am further indebted to express thanks to the ‘DLE Forschungsservice und Internationale Beziehungen’, who helped me complete my degree by attributing some funding to do research at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. I also wish to address special thanks to Prof. Misao Dean from the University of Victoria for letting me join some inspiring discussions in her ‘Core Seminar on Literatures of the West Coast’, which gave me the opportunity to exchange ideas with other students working in the field of Canadian literature. Lastly, I warmly thank my parents Dr. Hubert and Anna Zinöcker for their devoted emotional support and advice, and for sharing their knowledge and experience with me throughout my education. -

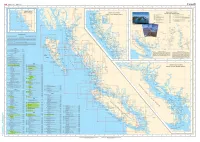

CHS Index Chart

Fisheries and Oceans Pi'lches et Oceans Canada Canada Canada ••• 137 ° 136 " 134" 133 ° 131° 129 ° ,.. 126 ° 125 " 124 " 123° 122° 119° 124 ° 118 ° GENERAL CHARTS CARTES GENERALES SMALL-CRAFT CHARTS REV ILLAG IGEDO LARGER SCALE CHARTS ISLAND CARTES POUR EMBARCATIONS CARTES A PLUS GRANDE ECHELLE 3050 Kootenay Lake and Rovet 75 000 3311 Sunshtno Coast- Vancouver Ha rbour lo/A 3052 Okanagan Lako so 000 Desolatoon Sound 40 000 3053 Shuswap Lake so 000 331:2 JerviS Intel ond/et Do•o latoon Sound 0 305S Waneta to /~ Hugh Keen leyside Dam 20 000 Vo,ous Scolo•JEche tle• vo"h• > z 3056 Hugh Koon loySido Dam to/A Burlon 40 000 3313 Gull Islands and Ad jacent Watotways/el les Vo1es Navigables Ad1acentes ~ ' 3057 Button IO/~ 1\rrowhood 40 000 Variou• Scale•/Echel le• vo"~"' 3058 Arrowhead lo/6 Rovo lotoko Go «m• 20 000 3488 Fro5er River/F I&uve Fraser, Cre•<ent l5land 3061 " "'"'on Lake and/ol Hamson R1ver '""'' to/~ Hon loon Mills 20 000 Harrison Lake 40 000 3469 Fraser Rovor/Fiouve Fr8set, Pattullo B"dgo Harrison R1ver 30 000 to/a Crescent Is land 20 000 Pitt River and/ot Poll l ak e 25 000 Stuaot L a~e (Not•howniP••rnd•qu o!) 50 000 54 " ~f--- ' ~ 0 "" I < ''"0' 't)Go iUn "?1- Cocoov• 3053 Foo ..o<o o l 0 "' GJ ,. Shu wap .•. Lake CANAOA !'; "'""""'' •·o~ d 130" 125° 120 " •5"omouo .,cocho Cceo> ,... ,. ' GJ ... ' <om l oops ~ DIXON E'N TRANCE' LEGENO/LEGENDE • •• • Scales smaller ttlan 1"40 000 Ectlellas plus petites qua 1:40 000 '' GJ Scales 1:40 000 and larger Ectlelles 1: 40 000 et plus grande& CHART SCALE Chart soale os the rat10 of one umt of d1stance 011 the cha" to the actual d.stance on the Earth's surface expressed on tho same unots. -

LU Boundary Rationale

DMC - Rationale Statement Mid Coast Forest District Landscape Unit Rationale Statement Landscape Unit Area (ha) Rationale Other # Name Mountain Islands Total Boundary Description Size Topography/Ecology/Hydrology Watersheds/Islands BEC Comments 1 King Island 40759 40759 Western boundary follows the topographic features southern boundary of landscape Jenny Inlet, Fog Creek, CWHms2 height of land which separates are similar to those unit established along height of Green River, Loken CWHvm1 watersheds flowing into Jenny Inlet located in complex land at the ecological transition Creek, Hole in the Wall, CWHvm2 from those watersheds flowing into coastal mountains- from hypermaritime to maritime and several unnamed CWHvm3 Fisher Channel and Burke within recommended biogeoclimatic subzones streams and MHmm1 Channel. Bound by water on three target size range for waterbodies ATc sides (Labouchere Channel, Burke complex coastal Channel and Dean Channel). mountains 2 Labouchere 50803 50803 Eastern boundary follows the within recommended height of land encompassing entire Nusash Creek, CWHms2 height of land which excludes target size range for watershed-ecosystem remains Nooseseck Creek, and CWHvm3 drainage into Nieumiamus Creek complex coastal intact-southern, western, and several unnamed MHmm1 and follows height of land west to mountains. northeastern boundary established streams and ATc White Cliff Point. Height of land along large waterbody waterbodies. encompassing Nusash Creek to the north and associated tributaries which flow into Dean Channel. 3 Saloompt 69049 69049 Height of land encompassing within recommended height of land encompassing entire Saloompt River, CWHds2 watersheds flowing into Saloompt target size range for watersheds, excluding those Noosgulch River, CWHms2 River, Noosgulch River, complex coastal portions within Landscape Unit #5 Tseapseahoolz Creek, CWHws2 Necleetsconnay River and mountains (Bella Coola)-ecosystem remains Talcheazoone Lakes, MHmm2 Nieumiamus Creek. -

Prepositional His and the Development of Morphological Case in Northern Wakashan1

Prepositional his and the development of morphological case in Northern Wakashan1 Katie Sardinha University of British Columbia This paper will present evidence for the historical development of “oblique” and “genitive” case-marking clitics in the Northern Wakashan language family from the Proto- North Wakashan preposition *his and an associated set of person-marking enclitics. The three Upper Northern Wakashan languages (Haisla, Heiltsuk, Oowekyala) are at intermediate stages of a process whereby a remnant of the preposition his/yis together with its associated person- marking enclitics is becoming enclitic to the prosodic word prior to the noun phrase it introduces or replaces; this can be taken as evidence that these languages are moving towards developing case-marking such as that which exists in Kwak’wala. Correspondences between the synchronic distribution and phonology of the Kwak’wala oblique and third-person possessive clitics and that of his/yis prepositional constructions in the Upper Northern Wakashan languages provide additional evidence for an historical relationship. Prior to the development of morphological case, prepositions themselves seem to have been innovated in the Northern Wakashan language branch from verbal and demonstrative roots. This situation indicates a deep syntactic divide, and significant time depth, between the Northern and Southern branches of Wakashan. 1 Introduction The aim of this paper is to develop an historical hypothesis to account for the innovation of two Northern Wakashan syntactic features which are conspicuously absent in the Southern Wakashan branch: the presence of prepositions, and the occurrence of varying degrees of morphological case- marking. More specifically, I will be presenting evidence for two historical 1 I would like to thank my Kwak’wala consultant Ruby Dawson Cranmer for sharing her language with me, my supervisor Henry Davis, and the members of the 2009-2010 UBC Field Methods class.