Imagining Europe: Memory, Visions, and Counter-Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northeast Asia: Obstacles to Regional Integration the Interests of the European Union

Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Discussion Paper Ludger Kühnhardt Northeast Asia: Obstacles to Regional Integration The Interests of the European Union ISSN 1435-3288 ISBN 3-936183-52-X Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Walter-Flex-Straße 3 Tel.: +49-228-73-4952 D-53113 Bonn Fax: +49-228-73-1788 C152 Germany http: //www.zei.de 2005 Prof. Dr. Ludger Kühnhardt, born 1958, is Director at the Center for European Integration Studies (ZEI). Between 1991 and 1997 he was Professor of Political Science at Freiburg University, where he also served as Dean of his Faculty. After studies of history, philosophy and political science at Bonn, Geneva, Tokyo and Harvard, Kühnhardt wrote a dissertation on the world refugee problem and a second thesis (Habilitation) on the universality of human rights. He was speechwriter for Germany’s Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker and visiting professor at various universities all over the world. His recent publications include: Europäische Union und föderale Idee, Munich 1993; Revolutionszeiten. Das Umbruchjahr 1989 im geschichtlichen Zusammenhang, Munich 1994 (Turkish edition 2003); Von der ewigen Suche nach Frieden. Immanuel Kants Vision und Europas Wirklichkeit, Bonn 1996; Beyond divisions and after. Essays on democracy, the Germans and Europe, New York/Frankfurt a.M. 1996; (with Hans-Gert Pöttering) Kontinent Europa, Zurich 1998 (Czech edition 2000); Zukunftsdenker. Bewährte Ideen politischer Ordnung für das dritte Jahrtausend, Baden-Baden 1999; Von Deutschland nach Europa. Geistiger Zusammenhalt und außenpoliti- scher Kontext, Baden-Baden 2000; Constituting Europe, Baden- Baden 2003. -

French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana

The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana Passman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Donald M. Reid Dr. Christopher R. Browning Dr. Konrad H. Jarausch Dr. Alice Kaplan Dr. Lloyd Kramer Dr. Jay M. Smith ©2008 Elana Passman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ELANA PASSMAN The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 (under the direction of Donald M. Reid) Through a series of case studies of French-German friendship societies, this dissertation investigates the ways in which activists in France and Germany battled the dominant strains of nationalism to overcome their traditional antagonism. It asks how the Germans and the French recast their relationship as “hereditary enemies” to enable them to become partners at the heart of today’s Europe. Looking to the transformative power of civic activism, it examines how journalists, intellectuals, students, industrialists, and priests developed associations and lobbying groups to reconfigure the French-German dynamic through cultural exchanges, bilingual or binational journals, conferences, lectures, exhibits, and charitable ventures. As a study of transnational cultural relations, this dissertation focuses on individual mediators along with the networks and institutions they developed; it also explores the history of the idea of cooperation. Attempts at rapprochement in the interwar period proved remarkably resilient in the face of the prevalent nationalist spirit. While failing to override hostilities and sustain peace, the campaign for cooperation adopted a new face in the misguided shape of collaborationism during the Second World War. -

Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics After 1945'

H-German Morina on Forner, 'German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945' Review published on Monday, April 18, 2016 Sean A. Forner. German Intellectuals and the Challenge of Democratic Renewal: Culture and Politics after 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. xii +383 pp. $125.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-107-04957-4. Reviewed by Christina Morina (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) Published on H-German (April, 2016) Commissioned by Nathan N. Orgill Envisioning Democracy: German Intellectuals and the Quest for Democratic Renewal in Postwar German As historians of twentieth-century Germany continue to explore the causes and consequences of National Socialism, Sean Forner’s book on a group of unlikely affiliates within the intellectual elite of postwar Germany offers a timely and original insight into the history of the prolonged “zero hour.” Tracing the connections and discussions amongst about two dozen opponents of Nazism, Forner explores the contours of a vibrant debate on the democratization, (self-) representation, and reeducation of Germans as envisioned by a handful of restless, self-perceived champions of the “other Germany.” He calls this loosely connected intellectual group a network of “engaged democrats,” a concept which aims to capture the broad “left” political spectrum they represented--from Catholic socialism to Leninist communism--as well as the relative openness and contingent nature of the intellectual exchange over the political “renewal” of Germany during a time when fixed “East” and “West” ideological fault lines were not quite yet in place. Forner enriches the already burgeoning historiography on postwar German democratization and the role of intellectuals with a profoundly integrative analysis of Eastern and Western perspectives. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

The Experience of the German Soldier on the Eastern Front

AUTONOMY IN THE GREAT WAR: THE EXPERIENCE OF THE GERMAN SOLDIER ON THE EASTERN FRONT A THESIS IN History Presented to the Faculty of the University Of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By Kevin Patrick Baker B.A. University of Kansas, 2007 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 ©2012 KEVIN PATRICK BAKER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AUTONOMY IN THE GREAT WAR: THE EXPERIENCE OF THE GERMAN SOLDIER ON THE EASTERN FRONT Kevin Patrick Baker, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT From 1914 to 1919, the German military established an occupation zone in the territory of present day Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia. Cultural historians have generally focused on the role of German soldiers as psychological and physical victims trapped in total war that was out of their control. Military historians have maintained that these ordinary German soldiers acted not as victims but as perpetrators causing atrocities in the occupied lands of the Eastern Front. This paper seeks to build on the existing scholarship on the soldier’s experience during the Great War by moving beyond this dichotomy of victim vs. perpetrator in order to describe the everyday existence of soldiers. Through the lens of individual selfhood, this approach will explore the gray areas that saturated the experience of war. In order to gain a better understanding of how ordinary soldiers appropriated individual autonomy in total war, this master’s thesis plans to use an everyday-life approach by looking at individual soldiers’ behaviors underneath the canopy of military hegemony. -

First World War Centenary Poetry Collection

First World War Centenary Poetry Collection 28th July 2014 All items in this collection are in the U.S. Public Domain owing to date of publication. If you are not in the U.S.A., please check your own country's copyright laws. Whether an item is still in copyright will depend on the author's date of death. 01 Preface to Poems by Wilfred Owen (1893 - 1918) This Preface was found, in an unfinished condition, among Wilfred Owen's papers after his death. The (slightly amended) words from the preface “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity” are inscribed on the memorial in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey. 02 For the Fallen by Laurence Binyon (1869 - 1943) Published when the Battle of the Marne was raw in people's memories, For the Fallen was written in honour of the war dead. The fourth verse including the words “We will remember them” has become the Ode of Remembrance to people of many nations and is used in services of remembrance all over the world. 03 [RUSSIAN] Мама и убитый немцами вечер (Mama i ubity nemcami vecher) by Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893 - 1930) В стихах «Война объявлена!» и «Мама и убитый немцами вечер» В.В. Маяковский описывает боль жертв кровавой войны и свое отвращение к этой войне. In this poem “Mama and the Evening Killed by the Germans” Mayakovsky describes the victims' pain of bloody war and his disgust for this war. 04 To Germany by Charles Hamilton Sorley (1895 - 1915) Sorley is regarded by some, including John Masefield, as the greatest loss of all the poets killed during the war. -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

Theory and Interpretation of Narrative) Includes Bibliographical References and Index

Theory and In T e r p r e Tati o n o f n a r r ati v e James Phelan and Peter J. rabinowitz, series editors Postclassical Narratology Approaches and Analyses edited by JaN alber aNd MoNika FluderNik T h e O h i O S T a T e U n i v e r S i T y P r e ss / C O l U m b us Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Postclassical narratology : approaches and analyses / edited by Jan Alber and Monika Fludernik. p. cm. — (Theory and interpretation of narrative) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-5175-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-5175-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1142-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1142-9 (cloth : alk. paper) [etc.] 1. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Alber, Jan, 1973– II. Fludernik, Monika. III. Series: Theory and interpretation of narrative series. PN212.P67 2010 808—dc22 2010009305 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1142-7) Paper (ISBN 978-0-8142-5175-1) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9241-9) Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction Jan alber and monika Fludernik 1 Part i. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „Die völkerrechtliche Klassifizierung von bewaffneten Konflikten und deren Auswirkung auf die Planung und Durchführung militärischer Operationen“ Verfasser Mag. iur. Karl EDLINGER angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Rechtswissenschaften (Dr. iur.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 783 101 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Rechtswissenschaften Betreuer: Prof. MMag. Dr. August REINISCH, LL.M. Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................. iii 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................. 1 2 Einführung in das humanitäre Völkerrecht ........................................... 7 3 Rechtsquellen des humanitären Völkerrechts ................................... 10 3.1 Die Genfer Abkommen und deren Zusatzprotokolle ............................................ 14 3.1.1 Anwendungsbereich der Genfer Abkommen und der Zusatzprotokolle ........... 18 3.1.1.1 Erklärte Kriege .............................................................................................. 21 3.1.1.2 Internationale bewaffnete Konflikte .............................................................. 23 3.1.1.3 Militärische Besetzung .................................................................................. 31 3.1.1.4 Bewaffnete Konflikte, die keinen internationalen Charakter haben.............. 39 3.1.1.5 Klassische Bürgerkriege ............................................................................... -

Ebook Download TOM HANKS CAREER in ORBIT

TOM HANKS CAREER IN ORBIT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Quinlan | 96 pages | 01 Oct 1998 | PAVILION BOOKS | 9780713480733 | English | London, United Kingdom TOM HANKS CAREER IN ORBIT PDF Book Best Actor Cast Away Larry Crowne Roger Ebert. They were not at all snobbish. Best Actor The Post The Extra Terrestrial , the co-stars he often reunited with, and how his father-in-law inspired The Terminal. Learn more. They can save the cost of a launch, just give me a few more birthdays then come and get me. A look at who could be nominated for Best Director at the upcoming Oscars. But I think I asked my agent. Some things are good for everyone, and some things are a waste of life and resources. The Terminal Roger Ebert. We made it like the still impoverished former Eastern Bloc nation that didn't have a thing. The broad success with the fantasy-comedy Big established him as a major Hollywood talent, both as a box office draw and within the film industry as an actor. I would see whatever Jason Robards did. Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson are still quarantined in Australia, and she, at least, is going a bit stir crazy. Newport, Campbell County, Kentucky, July 10, , d. That's more than enough," Obama said of Hanks at the ceremony. I've made an awful lot of movies that didn't make any sense, and didn't make any money, but that doesn't alter the work that goes into it, or even what your opinion of it is. -

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism By

Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anton Kaes, Chair Professor Martin Jay Professor Linda Williams Fall 2015 Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism © 2015 by Nicholas Walter Baer Abstract Absolute Relativity: Weimar Cinema and the Crisis of Historicism by Nicholas Walter Baer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Anton Kaes, Chair This dissertation intervenes in the extensive literature within Cinema and Media Studies on the relationship between film and history. Challenging apparatus theory of the 1970s, which had presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship, the ‘historical turn’ of recent decades has prompted greater attention to transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience. In my view, while film scholarship has subsequently emphasized the historicity of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, it has all too often left the very concept of history underexamined and insufficiently historicized. In my project, I propose a more reflexive model of historiography—one that acknowledges shifts in conceptions of time and history—as well as an approach to studying film in conjunction with historical-philosophical concerns. My project stages this intervention through a close examination of the ‘crisis of historicism,’ which was widely diagnosed by German-speaking intellectuals in the interwar period. -

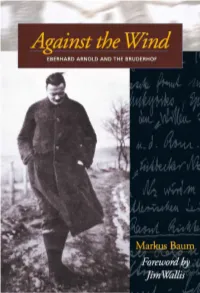

Against the Wind E B E R H a R D a R N O L D a N D T H E B R U D E R H O F

Against the Wind E B E R H A R D A R N O L D A N D T H E B R U D E R H O F Markus Baum Foreword by Jim Wallis Original Title: Stein des Anstosses: Eberhard Arnold 1883–1935 / Markus Baum ©1996 Markus Baum Translated by Eileen Robertshaw Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 2015, 1998 by Plough Publishing House All rights reserved Print ISBN: 978-0-87486-953-8 Epub ISBN: 978-0-87486-757-2 Mobi ISBN: 978-0-87486-758-9 Pdf ISBN: 978-0-87486-759-6 The photographs on pages 95, 96, and 98 have been reprinted by permission of Archiv der deutschen Jugendbewegung, Burg Ludwigstein. The photographs on pages 80 and 217 have been reprinted by permission of Archive Photos, New York. Contents Contents—iv Foreword—ix Preface—xi CHAPTER ONE 1 Origins—1 Parental Influence—2 Teenage Antics—4 A Disappointing Confirmation—5 Diversions—6 Decisive Weeks—6 Dedication—7 Initial Consequences—8 A Widening Rift—9 Missionary Zeal—10 The Salvation Army—10 Introduction to the Anabaptists—12 Time Out—13 CHAPTER TWO 14 Without Conviction—14 The Student Christian Movement—14 Halle—16 The Silesian Seminary—18 Growing Responsibility in the SCM—18 Bernhard Kühn and the EvangelicalAlliance Magazine—20 At First Sight—21 Against the Wind Harmony from the Outset—23 Courtship and Engagement—24 CHAPTER THREE 25 Love Letters—25 The Issue of Baptism—26 Breaking with the State Church—29 Exasperated Parents—30 Separation—31 Fundamental Disagreements among SCM Leaders—32 The Pentecostal Movement Begins—33