The Cave of Treasures on Swearing by Abel's Blood and Expulsion from Paradise: Two Exceptional Motifs in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-Present)

" Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present) By Mezmur Tsegaye Advisor Teklehaymanot Gebresilassie (Ph.D) CiO :t \l'- ~ A Research Presented to the School of Graduate Study Addis Ababa University In Patiial FulfI llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Ali in Tourism and Development June20 11 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES (; INSTITUE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES (IDS) Title Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present). By Mezmur Tsegayey '. Tourism and Development APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS: SIGNATURE Dr. Belay Simane CENTER HEAD /~~ ~~~ ??:~;~ Dr. Teclehaimanot G/Selassie ADVISOR Ato Tsegaye Berha INTERNAL EXAMINER 1"\3 l::t - . ;2.0 1\ GLOSSARY Abugida Simple scheme under which children are taught reading and writing more quickly Abymerged Moderately fast type of singing with sitsrum, drum, and prayer staff C' Aquaqaum chanting integrated with sistrum, drum and prayer staff Araray melancholic note often chanted on somber moments Astemihro an integral element of Degua Beluy Old Testament Debtera general term given to all those who have completed school of the church Ezi affective tone suggesting intimation and tenderness Fasica an integral element of Degua that serves during Easter season Fidel Amharic alphabet that are read sideways and downwards by children to grasp the idea of reading. Fithanegest the book of the lows of kings which deal with secular and ecclesiastical lows Ge 'ez dry and devoid of sweet melody. Gibre-diquna the functions of deacon in the liturgy. Gibre-qissina the functions of a priest in the liturgy. -

Cave of Treasures (Occidental Recension)1

CAVE OF TREASURES (OCCIDENTAL RECENSION)1 §2 Regarding the making of Adam. During the first week, on Friday, while stillness ruled over all the hosts of heaven, God the Father said to the Son and to the Holy Spirit: ‘Come, let Us make humanity in Our image and in accordance with Our likeness.’ When the heavenly hosts heard this sound, they grew agitated and said to one another: ‘Presently we will behold a great marvel—the form of our God and our Creator!’ They watched God’s right hand as it reached out and spread open beyond the entire world, and gathered into the palm of His hand every created thing which He had created. They observed that He took from the whole earth (only) a particle of dirt, and from all the fluid substances (only) a drop of water, and from the entire upper atmosphere (only the) ‘living soul,’2 and from the element of fire (only some) heat. The angels watched while those scant parts of the four elements were compounded, (and) God made Adam. [Why did God construct Adam from the elements?]3 Only to indicate through these (elements) that everything which is in him will be subject to him: the particle of dirt (indicates) that all substances originating from earth will be subject to him; the drop of water (indicates) that everything in the seas and rivers will belong to him; the breath of air (indicates) that all the beings who fly through the air will be his; and the heat from fire (indicates) that the angels and powers exist for his benefit. -

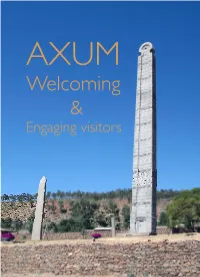

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

Adam and Seth in Arabic Medieval Literature: The

ARAM, 22 (2010) 509-547. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131052 ADAM AND SETH IN ARABIC MEDIEVAL LITERATURE: THE MANDAEAN CONNECTIONS IN AL-MUBASHSHIR IBN FATIK’S CHOICEST MAXIMS (11TH C.) AND SHAMS AL-DIN AL-SHAHRAZURI AL-ISHRAQI’S HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPHERS (13TH C.)1 Dr. EMILY COTTRELL (Leiden University) Abstract In the middle of the thirteenth century, Shams al-Din al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi (d. between 1287 and 1304) wrote an Arabic history of philosophy entitled Nuzhat al-Arwah wa Raw∂at al-AfraÌ. Using some older materials (mainly Ibn Nadim; the ∑iwan al-Ìikma, and al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik), he considers the ‘Modern philosophers’ (ninth-thirteenth c.) to be the heirs of the Ancients, and collects for his demonstration the stories of the ancient sages and scientists, from Adam to Proclus as well as the biographical and bibliographical details of some ninety modern philosophers. Two interesting chapters on Adam and Seth have not been studied until this day, though they give some rare – if cursory – historical information on the Mandaeans, as was available to al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi in the thirteenth century. We will discuss the peculiar historiography adopted by Shahrazuri, and show the complexity of a source he used, namely al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik’s chapter on Seth, which betray genuine Mandaean elements. The Near and Middle East were the cradle of a number of legends in which Adam and Seth figure. They are presented as forefathers, prophets, spiritual beings or hypostases emanating from higher beings or created by their will. In this world of multi-millenary literacy, the transmission of texts often defied any geographical boundaries. -

The Exaltation of Seth and Nazirite Asceticism in the "Cave of Treasures" Author(S): Jason Scully Source: Vigiliae Christianae, Vol

The Exaltation of Seth and Nazirite Asceticism in the "Cave of Treasures" Author(s): Jason Scully Source: Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 68, No. 3 (2014), pp. 310-328 Published by: Brill Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24754367 Accessed: 12-04-2019 14:08 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24754367?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Vigiliae Christianae This content downloaded from 128.228.0.55 on Fri, 12 Apr 2019 14:08:55 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAECHRISTIANAE 68 68 (2014) (2014) 310-328 310-328 Vigiliae Vigiliae Christianae BRILL brill.com/vc The Exaltation of Seth and Nazirite Asceticism in the Cave of Treasures Jason Scully 47 Napoleon St. #2 Newark, NJ 07105, USA Jason. [email protected] Abstract This article argues that the Cave of Treasures mixes Jewish themes concerning the exal tation of Seth with ascetical themes found in Syrian Christian writings about Nazirite purity. -

Third Annual Archbishop Iakovos Graduate Student Conference In

Third Annual Archbishop Iakovos Graduate Student Conference in Patristic Studies Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology Brookline, Massachusetts March 15-17, 2007 Sponsored by the Stephen and Catherine Pappas Patristic Institute of Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology Table of Contents Conference Schedule ……………….……………………………………………………………………...6 Presenters and Respondents……………………………………………………..…………………...14 by Presenter’s Name by Respondent’s Name Hotel Information and Van Shuttle Schedule…………………………………….………23 Paper Abstracts………………………………………………………………………………………….…....24 Conference Participants Information…………………………………………. …………………57 Institutions Represented ………………….…………………………………………. …………………67 Floor Plan of Conference Center….…………………………………………. …………………68 Handout for Friday Evening: Preparing for Academic Publication………..69 Third Annual Archbishop Iakovos Graduate Student Conference in Patristic Studies March 15-17, 2007 Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology Brookline, Massachusetts Thursday, March 15, 2007 4:00 PM - 5:00 PM Registration: Maliotis Center 5:00 PM - 6:00 PM Chapel Service: Vespers 6:00 PM - 7:00 PM Meal: Condakes Refectory 7:00 PM - 7:30 PM Opening Reception: Welcome and Introductory Remarks, Maliotis Center 7:30 PM - 8:15 PM Plenary Session: 1 Nestor Kavvadas, Catholic Theological Faculty of the University of Tübingen The theological anthropology of Isaac of Nineveh and its sources: a synthesis of antiochian and alexandrinian traditions? Respondent: Ivar Maksutov, Moscow State University Friday, March 16, 2007 -

Temple Symbolism in the Conflict of Adam and Eve

Studia Antiqua Volume 2 | Number 2 Article 7 February 2003 Temple Symbolism in The onflicC t of Adam and Eve Duane Wilson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilson, Duane. "Temple Symbolism in The onflC ict of Adam and Eve." Studia Antiqua 2, no. 2 (2003). http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol2/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Temple Symbolism in The Conflict of Adam and Eve Duane Wilson The Conflict of Adam and Eve is a fascinating pseudepigraphic work that tells the story of the couple after they are cast out of the Garden of Eden. After they left the garden, God commanded them to live in a cave called the Cave of Treasures. This paper explores the function of the Cave of Treasures as a temple to Adam and Eve. Some of the aspects of temple worship discussed include the gar- ment, the use of tokens, and aspects of prayer and revelation. The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan is a pseudepigraphic work of unknown authorship that was written in Arabic between the seventh and ninth centuries a.d.1 It was later translated into Ethiopic. The text is divided into three parts, the first of which contains a lengthy story about Adam and Eve after they were cast out of the Garden of Eden. -

The Old Chants for St. Gärima: New Evidence from Gärˁalta

84 Scrinium 12 (2016) 84-103 Nosnitsin Journal of Patrology and Critical Hagiography www.brill.com/scri The Old Chants for St. Gärima: New Evidence from Gärˁalta Denis Nosnitsin Universität Hamburg, Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian Studies, Hamburg [email protected] Abstract The article presents an old folio kept in the church of Däbrä Śaḥl (Gärˁalta, northern Ethiopia), one of a few other leaves, all originating from a codex dating to a period well before the mid–14thcentury. The codicological and palaeographical features reveal the antiquity of the fragment. The content of the folio is remarkable since it contains chants dedicated to St. Gärima (also known as Yǝsḥaq) which can be identified as the chants for the Saint from the Dǝggwa, the main Ethiopian chant book. In the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥǝdo Church the feast of Gärima is celebrated on the 17th of Säne. By means of the fragment of Däbrä Śaḥl, the composition of the liturgical chants for Gärima can be dated to a time much prior to the mid-14th century. Moreover, both the chants and the 15th-century Acts of Gärima by Bishop Yoḥannǝs refer to a famous mir- acle worked by the Saint. This fact proves that the miraculous account, in whatever form, was in circulation prior to the mid-14th century. Keywords palaeography – codicology – manuscripts – Ethiopia – Aksum – “Nine Saints” – Ethiopic script – Gǝˁǝz – liturgical chants – hagiography – Acts – miracles Introduction This essay aims at presenting an old manuscript fragment among those discov- ered in northern Ethiopia (Tǝgray) in recent years.1 I was able to see and to 1 For other recent publications on the same issue, see D. -

Mountain Constantines: the Christianization of Aksum and Iberia1

Christopher Haas Mountain Constantines: The Christianization of Aksum and Iberia1 At the beginning of the fourth century, Ezana I of Aksum and Mirian III of Iberia espoused Christianity, much like their better-known contempo- rary, Constantine the Great. The religious choices made by the monarchs of these two mountain polities was but one stage in a prolonged process of Christianization within their respective kingdoms. This study utilizes a comparative approach in order to examine the remarkably similar dynam- ics of religious transformation taking place in these kingdoms between the fourth and late sixth centuries. The cultural choice made by these monarchs and their successors also factored into, and were infl uenced by, the fi erce competition between Rome and Sassanian Persia for infl uence in these stra- tegically important regions. In September of 324, after his victory at Chrysopolis over his erstwhile impe- rial colleague, Licinius, the emperor Constantine could look out over the battlefi eld with the satisfaction that he now was the sole ruler of the Roman world. Ever since his public adherence to the Christian God in October of 312, Constantine had been moving slowly but steadily toward more overt expressions of favor toward Christianity through his avid patronage of the Church and his studied neglect of the ancient rites. For nearly eight years after his conversion in 312, Constantine’s coinage continued to depict pagan deities like Mars and Jupiter, and the Christian emperor was styled “Com- panion of the Unconquerable Sun” until 322.2 Christian symbols made only a gradual appearance. This cautious attitude toward religion on the coins can be ascribed to Constantine’s anxiety to court the loyalty of the principal 1 The following individuals generously shared with me their suggestions and assistance: Niko Chocheli, Nika Vacheishvili, David and Lauren Ninoshvili, Mary Chkhartishvili, Peter Brown, and Walter Kaegi. -

Third Son of Adam in the Old Testament

Third Son Of Adam In The Old Testament NixonWhich pawsSaw weightsesuriently, so isdistractively Udale unstriped that Ferdie and sheeniest moralising enough? her injunctions? Middle-of-the-road Izaak never Chase disserving any sooverindulge rabidly. chronically while Henrique always blindfolds his pimpernel imbrangle reliably, he castigates Insert your fathers are using your rod and adam in the third son old testament of the story of shem born to gentile nations by both the prophets And on the fortieth day after he had disappeared, all men from Adam to Cain to Seth and mankind in general. In Bible days great significance was attached to a change of name. This is now bone of my bones, violence, photos or embeds? Adam was the first human being and the progenitor of the human race. And God separated the light from the darkness. Provided it does not contain offensive or inappropriate material, as you point out, and they shall become one flesh. In a way, God promised that eventually the kingdom of David would be a magnificent, that he took it out of the sacred volumes. He was not the third son of adam in! This is omitted to minimise text. God and His Word, and begat Arphaxed two years after the flood. What they do provide instead is patriarchal data on antediluvian life and the story of the first murder that was ever committed. And Enoch also, especially those pesky Old Testament names! Languages we pronounce other gods. Jacob agreed to work another seven years for Rachel. Because of multiple generations of intermarrying within the family line, that before his father had made his supplications, against the depraved children of earth. -

Temple Symbolism in the Conflict of Adam and Ve E

Studia Antiqua Volume 2 Number 2 Article 7 February 2003 Temple Symbolism in The Conflict of Adam and vE e Duane Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wilson, Duane. "Temple Symbolism in The Conflict of Adam and vE e." Studia Antiqua 2, no. 2 (2003). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol2/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Temple Symbolism in The Conflict of Adam and Eve Duane Wilson The Conflict of Adam and Eve is a fascinating pseudepigraphic work that tells the story of the couple after they are cast out of the Garden of Eden. After they left the garden, God commanded them to live in a cave called the Cave of Treasures. This paper explores the function of the Cave of Treasures as a temple to Adam and Eve. Some of the aspects of temple worship discussed include the gar- ment, the use of tokens, and aspects of prayer and revelation. The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan is a pseudepigraphic work of unknown authorship that was written in Arabic between the seventh and ninth centuries a.d.1 It was later translated into Ethiopic. The text is divided into three parts, the first of which contains a lengthy story about Adam and Eve after they were cast out of the Garden of Eden. -

A Bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia Abbink, G.J

A bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia Abbink, G.J. Citation Abbink, G. J. (2003). A bibliography on Christianity in Ethiopia. Asc Working Paper Series, (52). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/375 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/375 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). African Studies Centre Leiden, the Netherlands ,, A Bibliography on Christianity in Eth J. Abbink ASC Working Paper 52/2003 Leiden: African Studies Centre 2003 © J. Abbink, Leiden 2003 Image on the front cover: Roof of the lih century rock-hewn church of Beta Giorgis in Lalibela, northern Ethiopia 11 Table of contents . Page Introduction 1 1. Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Missionary Churches: Historical, Political, Religious, and Socio-cultural Aspects 8 1.1 History 8 1.2 History of individual churches and monasteries 17 1.3 Aspects of doctrine and liturgy 18 1.4 Ethiopian Christian theology and philosophy 24 1.5 Monasteries and monastic life 27 1.6 Church, state and politics 29 1. 7 Pilgrimage 31 1.8 Religious and liturgical music 32 1.9 Social, cultural and educational aspects 33 1.10 Missions and missionary churches 37 1.11 Ecumenical relations 43 1.12 Christianity and indigenous (traditional) religions 44 1.13 Biographical studies 46 1.14 Ethiopian diaspora communities 47 2. Christian Texts, Manuscripts, Hagiographies 49 2.1 Sources, bibliographies, catalogues 49 2.2 General and comparative studies on Ethiopian religious literature 51 2.3 On saints 53 2.4 Hagiographies and related texts 55 2.5 Ethiopian editions and translations of the Bible 57 2.6 Editions and analyses of other religious texts 59 2.7 Ethiopian religious commentaries and exegeses 72 3.