Mountain Constantines: the Christianization of Aksum and Iberia1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-Present)

" Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present) By Mezmur Tsegaye Advisor Teklehaymanot Gebresilassie (Ph.D) CiO :t \l'- ~ A Research Presented to the School of Graduate Study Addis Ababa University In Patiial FulfI llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Ali in Tourism and Development June20 11 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES (; INSTITUE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES (IDS) Title Traditional Education of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Potential for Tourism Development (1975-present). By Mezmur Tsegayey '. Tourism and Development APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS: SIGNATURE Dr. Belay Simane CENTER HEAD /~~ ~~~ ??:~;~ Dr. Teclehaimanot G/Selassie ADVISOR Ato Tsegaye Berha INTERNAL EXAMINER 1"\3 l::t - . ;2.0 1\ GLOSSARY Abugida Simple scheme under which children are taught reading and writing more quickly Abymerged Moderately fast type of singing with sitsrum, drum, and prayer staff C' Aquaqaum chanting integrated with sistrum, drum and prayer staff Araray melancholic note often chanted on somber moments Astemihro an integral element of Degua Beluy Old Testament Debtera general term given to all those who have completed school of the church Ezi affective tone suggesting intimation and tenderness Fasica an integral element of Degua that serves during Easter season Fidel Amharic alphabet that are read sideways and downwards by children to grasp the idea of reading. Fithanegest the book of the lows of kings which deal with secular and ecclesiastical lows Ge 'ez dry and devoid of sweet melody. Gibre-diquna the functions of deacon in the liturgy. Gibre-qissina the functions of a priest in the liturgy. -

Continuity and Tradition: the Prominent Role of Cyrillian Christology In

Jacopo Gnisci Jacopo Gnisci CONTINUITY AND TRADITION: THE PROMINENT ROLE OF CYRILLIAN CHRISTOLOGY IN FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURY ETHIOPIA The Ethiopian Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest in the world. Its clergy maintains that Christianity arrived in the country during the first century AD (Yesehaq 1997: 13), as a result of the conversion of the Ethiopian Eunuch, narrated in the Acts of the Apostles (8:26-39). For most scholars, however, the history of Christianity in the region begins with the conversion of the Aksumite ruler Ezana, approximately during the first half of the fourth century AD.1 For historical and geographical reasons, throughout most of its long history the Ethiopian Church has shared strong ties with Egypt and, in particular, with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. For instance, a conspicuous part of its literary corpus, both canonical and apocryphal, is drawn from Coptic sources (Cerulli 1961 67:70). Its liturgy and theology were also profoundly affected by the developments that took place in Alexandria (Mercer 1970).2 Furthermore, the writings of one of the most influential Alexandrian theologians, Cyril of Alexandria (c. 378-444), played a particularly significant role in shaping Ethiopian theology .3 The purpose of this paper is to highlight the enduring importance and influence of Cyril's thought on certain aspects of Ethiopian Christology from the early developments of Christianity in the country to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Its aim, therefore, is not to offer a detailed examination of Cyril’s work, or more generally of Ethiopian Christology. Rather, its purpose is to emphasize a substantial continuity in the traditional understanding of the nature of Christ amongst Christian 1 For a more detailed introduction to the history of Ethiopian Christianity, see Kaplan (1982); Munro-Hay (2003). -

Tour to Georgia 10 Days /9 Nights

TOUR TO GEORGIA 10 DAYS /9 NIGHTS Day 1: Arrival at Tbilisi Meeting at the airport, transfer to the hotel. Free time. Overnight at the hotel in Tbilisi. Day 2. Tbilisi (B/L/-) Breakfast at the hotel. Tour of the historic part of the city, which begins with a visit to the Metekhi Temple, which is one of the most famous monuments in Tbilisi. This temple was honored in the 13th century, on the very edge of the stony shore of the Kura and the former fortress and residence of the Georgian kings. The first Georgian martyr, Queen Shushanika Ranskaya, was buried under the arches of the Metekhi temple. Inspection of the Tbilisi sulfur baths, which are built in the style of classical oriental architecture. These are low, squat buildings, covered with semicircular domes with large glass openings in the center, serving as windows that illuminate the interior, as the baths themselves are below ground level. In the old days, people here not only bathed, but also talked, lingering until dawn, and the city matchmakers arranged special days on special days. In the baths gave dinner parties, concluded trade deals. Walk on the square Maidan, which was the main shopping area of the city and along small streets known under the common name "Sharden". Narikala Fortress, which is the most ancient monument, a kind of "soul and heart of the city." The date of construction of the fortress is called approximately IV century AD, so it stands from the foundation of the city itself. Later, the fortress was expanded and completed several times. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

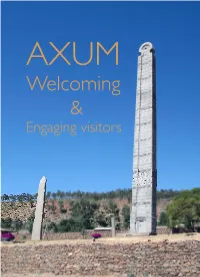

AXUM – Welcoming and Engaging Visitors – Design Report

Pedro Guedes (2010) AXUM – Welcoming and engaging visitors – Design report CONTENTS: Design report 1 Appendix – A 25 Further thoughts on Interpretation Centres Appendix – B 27 Axum signage and paving Presented to Tigray Government and tourism commission officials and stakeholders in Axum in November 2009. NATURE OF SUBMISSION: Design Research This Design report records a creative design approach together with the development of original ideas resulting in an integrated proposal for presenting Axum’s rich tangible and intangible heritage to visitors to this important World Heritage Town. This innovative proposal seeks to use local resources and skills to create a distinct and memorable experience for visitors to Axum. It relies on engaging members of the local community to manage and ‘own’ the various ‘attractions’ for visitors, hopefully keeping a substantial proportion of earnings from tourism in the local community. The proposal combines attitudes to Design with fresh approaches to curatorship that can be applied to other sites. In this study, propositions are tested in several schemes relating to the design of ‘Interpretation centres’ and ideas for exhibits that would bring them to life and engage visitors. ABSTRACT: Axum, in the highlands of Ethiopia was the centre of an important trading empire, controlling the Red Sea and channeling exotic African merchandise into markets of the East and West. In the fourth century (AD), it became one of the first states to adopt Christianity as a state religion. Axum became the major religious centre for the Ethiopian Coptic Church. Axum’s most spectacular archaeological remains are the large carved monoliths – stelae that are concentrated in the Stelae Park opposite the Cathedral precinct. -

“Little Girl, Get Up!” the Story of Bible Translation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2003.2.12.319 The Story of Bible Translation / Phil Noss “Little girl, get up!” The Story of Bible Translation Phil Noss To. koras, ion( soi. le,gw( e;geire “Little girl, I say to you, arise.” (RSV) “Little girl, get up!” (CEV) 1. Introduction The gospel writer Mark tells of a leader of the synagogue named Jairus who came to Jesus with a desperate request. His daughter was very ill and was dying and he asked Jesus to come and lay his hands on her so that she would be healed and would live. Jesus was apparently willing to help, but he was delayed on the way by a woman who wanted to be healed of an illness from which she had suffered for twelve years. Before he could reach the little girl, messengers arrived with the sad news that she had died. There was no longer any point in troubling the Teacher, they said. But Jesus did not accept the message and he did not want others to accept it either. “Do not fear, only believe,” he told those around him. He continued on the way to Jairus’ home, and when he arrived there, he remonstrated with those weeping outside the house. “She is not dead, only sleeping,” he announced. Then he went inside to the child, took her by the hand and said, “‘Talitha cum!’ which means ‘Little girl, get up!’” The narrator of the story reports, “The girl got straight up and started walking around” (CEV). Everyone was greatly surprised, but Jesus commanded them to tell no one what had happened and he instructed them to give the little girl something to eat! 2. -

Georgia/Abkhazia

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/HELSINKI March 1995 Vol. 7, No. 7 GEORGIA/ABKHAZIA: VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OF WAR AND RUSSIA'S ROLE IN THE CONFLICT CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................5 EVOLUTION OF THE WAR.......................................................................................................................................6 The Role of the Russian Federation in the Conflict.........................................................................................7 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Republic of Georgia ..............................................................................................8 To the Commanders of the Abkhaz Forces .....................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Russian Federation................................................................................................8 To the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus...........................................................................9 To the United Nations .....................................................................................................................................9 To the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe..........................................................................9 -

Politics and Christianity in Southwestern Ethiopia

Sociology and Anthropology 4(1): 29-36, 2016 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/sa.2016.040105 Religious Change among the Kore: Politics and Christianity in Southwestern Ethiopia Awoke Amzaye Assoma Department of Anthropology, Washington State University, USA Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract Although the introduction of Christianity to the the rapid expansion of Charismatic-Pentecostal Christianity Kore, southwestern Ethiopia, dates to the 14th and 15th among the Kore people of southwestern Ethiopia and its centuries, it remained marginal until Charismatic-Pentecost effects on Kore culture and belief. I seek to answer two al Christianity expanded and transformed the religious questions about the expansion of Charismatic-Pentecostal landscape of the Kore in the 20th century. This paper explores Christianity in Kore. (1) What historical situations enabled the historical and political factors behind this surge and its the rapid expansion of Charismatic-Pentecostal Christianity effects on Kore culture and belief. Based on literature review in Kore? (2) What are the impacts of this rapid expansion of and my field observations, I argue that the religious change Charismatic-Pentecostal Christianity on the Kore culture and in Kore reflects historically varying counter-hegemonic how does this relate to other African reactions to north Ethiopian domination. Contemporary Charismatic-Pentecostal movements? Anthropological religious change, the paper will show, needs to be writings on Christianity emphasize the ‘utilitarian’ and understood as counter-hegemonic reaction capable of ‘intellectualist’ 1 approaches to explain why people are reorganizing the Kore culture and belief in particular and the attracted to one or another form of religion [3, 4]. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title One Law for Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5qn8t4jf Author Spielman, David Benjamin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies by David Benjamin Spielman 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia by David Benjamin Spielman Master of Arts in African Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ghislaine E. Lydon, Chair This thesis historically traces the development and interactions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in Ethiopia. This analysis of the interactions between the Abrahamic faiths is primarily concerned with identifying notable periods of social cohesion in an effort to contest mainstream narratives that often pit the three against each other. This task is undertaken by incorporating a comparative analysis of the Ethiopian Christian code, the Fetha Nagast (Law of Kings), with Islamic and Judaic legal traditions. Identifying the common threads weaved throughout the Abrahamic legal traditions demonstrates how the historical development and periods of social cohesion in Ethiopia were facilitated. ii The thesis of David Benjamin Spielman is approved. Allen F. -

The Security of the Caspian Sea Region

16. The Georgian–Abkhazian conflict Alexander Krylov I. Introduction The Abkhaz have long populated the western Caucasus. They currently number about 100 000 people, speak one of the languages of the Abkhazo-Adygeyan (west Caucasian) language group, and live in the coastal areas on the southern slopes of the Caucasian ridge and along the Black Sea coast. Together with closely related peoples of the western Caucasus (for example, the Abazins, Adygeyans and Kabardians (or Circassians)) they play an important role in the Caucasian ethno-cultural community and consider themselves an integral part of its future. At the same time, the people living in coastal areas on the southern slopes of the Caucasian ridge have achieved broader communication with Asia Minor and the Mediterranean civilizations than any other people of the Caucasus. The geographical position of Abkhazia on the Black Sea coast has made its people a major factor in the historical process of the western Caucasus, acting as an economic and cultural bridge with the outside world. Georgians and Abkhaz have been neighbours from time immemorial. The Georgians currently number about 4 million people. The process of national consolidation of the Georgian nation is still far from complete: it includes some 20 subgroups, and the Megrelians (sometimes called Mingrelians) and Svans who live in western Georgia are so different in language and culture from other Georgians that it would be more correct to consider them as separate peoples. Some scholars, Hewitt, for example,1 suggest calling the Georgian nation not ‘Georgians’ but by their own name, Kartvelians, which includes the Georgians, Megrelians and Svans.2 To call all the different Kartvelian groups ‘Georgians’ obscures the true ethnic situation. -

The Role of the African Church in the 21St Century Global Mission: a Case Study of the Eecmy Global Mission Venture and Economic Mindset

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Art Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship Fall 12-18-2020 THE ROLE OF THE AFRICAN CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY GLOBAL MISSION: A CASE STUDY OF THE EECMY GLOBAL MISSION VENTURE AND ECONOMIC MINDSET WONDIMU M. GAME Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/ma_th Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation GAME, WONDIMU M., "THE ROLE OF THE AFRICAN CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY GLOBAL MISSION: A CASE STUDY OF THE EECMY GLOBAL MISSION VENTURE AND ECONOMIC MINDSET" (2020). Master of Art Theology Thesis. 92. https://scholar.csl.edu/ma_th/92 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Art Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF THE AFRICAN CHURCH IN THE 21ST CENTURY GLOBAL MISSION: A CASE STUDY OF THE EECMY GLOBAL MISSION VENTURE AND ECONOMIC MINDSET A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Practical in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Wondimu M. Game January, 2021 Approved by: Dr. Benjamin Haupt Thesis Advisor Dr.