In Search of the State. an Ethnography of Public Service Provision in Urban Niger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: an Historical Analysis, 1804-1960

Legacies of Colonialism and Islam for Hausa Women: An Historical Analysis, 1804-1960 by Kari Bergstrom Michigan State University Winner of the Rita S. Gallin Award for the Best Graduate Student Paper in Women and International Development Working Paper #276 October 2002 Abstract This paper looks at the effects of Islamization and colonialism on women in Hausaland. Beginning with the jihad and subsequent Islamic government of ‘dan Fodio, I examine the changes impacting Hausa women in and outside of the Caliphate he established. Women inside of the Caliphate were increasingly pushed out of public life and relegated to the domestic space. Islamic law was widely established, and large-scale slave production became key to the economy of the Caliphate. In contrast, Hausa women outside of the Caliphate were better able to maintain historical positions of authority in political and religious realms. As the French and British colonized Hausaland, the partition they made corresponded roughly with those Hausas inside and outside of the Caliphate. The British colonized the Caliphate through a system of indirect rule, which reinforced many of the Caliphate’s ways of governance. The British did, however, abolish slavery and impose a new legal system, both of which had significant effects on Hausa women in Nigeria. The French colonized the northern Hausa kingdoms, which had resisted the Caliphate’s rule. Through patriarchal French colonial policies, Hausa women in Niger found they could no longer exercise the political and religious authority that they historically had held. The literature on Hausa women in Niger is considerably less well developed than it is for Hausa women in Nigeria. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER

Co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING FOR CAPACITY BUILDING LET4CAP Law Enforcement Training for Capacity Building NIGER Downloadable Country Booklet DL. 2.5 (Ve 1.2) Dissemination level: PU Let4Cap Grant Contract no.: HOME/ 2015/ISFP/AG/LETX/8753 Start date: 01/11/2016 Duration: 33 months Dissemination Level PU: Public X PP: Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission) RE: Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission) Revision history Rev. Date Author Notes 1.0 20/03/2018 SSSA Overall structure and first draft 1.1 06/05/2018 SSSA Second version after internal feedback among SSSA staff 1.2 09/05/2018 SSSA Final version version before feedback from partners LET4CAP_WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable_2.5 VER1.2 WorkpackageNumber 2 Deliverable Deliverable 2.5 Downloadable country booklets VER V. 1 . 2 2 NIGER Country Information Package 3 This Country Information Package has been prepared by Eric REPETTO and Claudia KNERING, under the scientific supervision of Professor Andrea de GUTTRY and Dr. Annalisa CRETA. Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy www.santannapisa.it LET4CAP, co-funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union, aims to contribute to more consistent and efficient assistance in law enforcement capacity building to third countries. The Project consists in the design and provision of training interventions drawn on the experience of the partners and fine-tuned after a piloting and consolidation phase. © 2018 by LET4CAP All rights reserved. 4 Table of contents 1. Country Profile 1.1Country in Brief 1.2Modern and Contemporary History of Niger 1.3 Geography 1.4Territorial and Administrative Units 1.5 Population 1.6Ethnic Groups, Languages, Religion 1.7Health 1.8Education and Literacy 1.9Country Economy 2. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE POLITICS OF ELECTORAL REFORM IN FRANCOPHONE WEST AFRICA: THE BIRTH AND CHANGE OF ELECTORAL RULES IN MALI, NIGER, AND SENEGAL By MAMADOU BODIAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Mamadou Bodian To my late father, Lansana Bodian, for always believing in me ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want first to thank and express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Leonardo A. Villalón, who has been a great mentor and good friend. He has believed in me and prepared me to get to this place in my academic life. The pursuit of a degree in political science would not be possible without his support. I am also grateful to my committee members: Bryon Moraski, Michael Bernhard, Daniel A. Smith, Lawrence Dodd, and Fiona McLaughlin for generously offering their time, guidance and good will throughout the preparation and review of this work. This dissertation grew in the vibrant intellectual atmosphere provided by the University of Florida. The Department of Political Science and the Center for African Studies have been a friendly workplace. It would be impossible to list the debts to professors, students, friends, and colleagues who have incurred during the long development and the writing of this work. Among those to whom I am most grateful are Aida A. Hozic, Ido Oren, Badredine Arfi, Kevin Funk, Sebastian Sclofsky, Oumar Ba, Lina Benabdallah, Amanda Edgell, and Eric Lake. I am also thankful to fellow Africanists: Emily Hauser, Anna Mwaba, Chesney McOmber, Nic Knowlton, Ashley Leinweber, Steve Lichty, and Ann Wainscott. -

Trans-Sahara Highway Project

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND TRANS-SAHARA HIGHWAY (TSH) PROJECT COUNTRY : MULTINATIONAL (ALGERIA/NIGER/CHAD) PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT OITC DEPARTMENT November 2013 Translated Document TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 STRATEGIC THRUST AND RATIONALE ............................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Linkages with Country and Regional Strategies and Objectives ................................................. 1 1.2 Rationale for Bank Involvement ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Aid Coordination ...................................................................................................................................... 2 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Project Objectives and Components ......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Technical Solutions Adopted and Alternatives Explored ......................................................................... 5 2.3 Project Type .............................................................................................................................................. 6 2.4 Estimated Project Cost and Financing Arrangements ............................................................................... 7 2.5 Project Areas and Beneficiaries ............................................................................................................... -

ECFG-Niger-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment (Photos courtesy of IRIN News 2012 © Jaspreet Kindra). Niger Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Niger, focusing on unique cultural features of Nigerien society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Republique Du Niger

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Ministère de l’Hydraulique et de l’Assainissement Direction Générale des Ressources en eau Direction de l’Hydrogéologie ETAT DE MISE EN ŒUVRE DES ACTIVITES DU PROJET DANS LE COMPLEXE AQUIFERE DU LIPTAKO GOURMA AU NIGER RAF7011 – Gestion intégrée et durable des ressources en eau en Afrique axé sur les États Membres de la région du Sahel Vienne, du 05 au 08 Mai 2014 Présenté par Sanoussi RABE, Ingénieur Hydrogéologue DHGL/DGRE/MH/A PLAN DE L’EXPOSE 1. Présentation du complexe Aquifère du Liptako Gourma 2. Les principaux problèmes hydrogéologiques identifiés dans le bassin ; 3. Critères utilisés pour la sélection des points de prélèvement ; 4. Liste des personnes directement impliquées dans les activités ; 5. Principaux problèmes rencontrés lors des missions de terrain ; 6. Etat de lieux sur les données de base (Base des données et cartes thématiques de la zone du projet) 7. Conclusion et perspectives Introduction Introduction Capitale Niamey Superficie (km2) 1 267 000 Superficie de la zone d’intervention par pays (km2) 123 805 Densité (hbt/km2) 10 Population Ensemble 13 044 973 Zone ALG 4 839 638 Taux de croissance démographique 3,3 Ensemble 7+CUN Découpage administratif Zone ALG 2+CUN Introduction Le Liptako Gourma est une région enclavée aux conditions très difficiles du fait de la rareté des ressources en eaux dont les plus importantes sont situées dans des aquifères discontinus et dont les débits sont très faibles. Cette région qui regroupe le Burkina Faso, le Mali et le Niger.est concernée par le aquifères des grands bassins hydrogéologiques. Introduction 0 1 2 3 4 5 MALI 15 REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER 15 TA HO UA Projet RAF7011/AIEA %[ Ayorou CARTE DE LA REGION DU LIPTAKO GOURMA ILLELA OU ALLA M FILING UE ]' ]' Tillaberi ]%[' TERA 14 ]' 14 BIRN I N 'K ON N I N DOG ON DO UTC HI ]' NIAMEY ]' LO GA O E %[ S KOLLO ]' %[ Dosso BURKINA FASO ]' ]' SAY ]' 13 BIRN IN GA OU RE 13 30 0 30 60 Kilomètres 12 Gaya 12 %[]' 0 1 2 3 4 5 2. -

Le Journal De Jica Niger

L E J O U R N A L DE JICA NIGE R Bulletin d’information de la JICA - N i g e r N ゜ 0 0 9 j u i n 2 011 LES MOTS DU REPRESENTANT RESIDENT DE LA JICA AU NIGER Je voudrais féliciter tous les nigériens pour le retour du Niger à une vie constitutionnelle normale avec un gouvernement démocratiquement élu. C’est assurément un motif de fierté pour les nigériens surtout eu égard à la situation sociopolitique qui prévaut dans la plupart des pays de la sous région caractérisée par une certaine instabilité institutionnelle. L’Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) ne manquera pas cette opportunité pour contribuer, de manière significative, à la relance et au renforcement de la coopération technique et financière entre le Japon et le Niger dont les premiers jalons ont été posés en 1976. Dans son discours d’investiture SEM Mahamadou Issoufou, Président de la République du Niger, a réaffirmé sa détermination de mettre un accent particulier sur l’éducation de base, la Santé Publique et la sécurité alimentaire qui constituent de grands défis à relever. La JICA pour sa part, entend plus que par le passé, réitérer son ferme engagement et sa volonté d’œuvrer aux cotés des laborieuses populations nigériennes pour la recherche d’un mieux-être et d’un meilleur avenir. LES MOTS DU DIRECTEUR AMERIQUE ASIE OCEANIE (DAMAO) SUITE AU DEPART DEFINITIF DES VOLONTAIRES JAPONAIS DU NIGER Le retrait des volontaires japonais au Niger a été fortement ressenti par les SOMMAIRE communautés nigériennes. La coopération Nigéro -japonaise est l’une des plus fructueuse et couvre les domaines de CEREMONIE DE REMISE développement socio- économiques du Niger en l’occurrence l’Education, la santé, l’aide DE DON A LA SOPAMIN alimentaire, l’augmentation de la production agricole ainsi que plusieurs autres projets P.2 financés sur fonds de contrepartie. -

E6978b8c6f842788485463a7e1

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Planning to cope with tropical and subtropical climate change Original Planning to cope with tropical and subtropical climate change / Tiepolo, Maurizio; Ponte, Enrico; Cristofori, ELENA ISOTTA. - STAMPA. - Libro pubblicato sia in formato cartaceo che elettronico open access (DOI: 10.1515/9783110480795, e-ISBN 978-3-11-048079-5).(2016), pp. 1-380. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2624919 since: 2017-05-04T12:04:59Z Publisher: De Gruyter Open Ltd Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 17 December 2018 OPEN PLANNING TO COPE WITH TROPICAL AND SUBTROPICAL CLIMATE CHANGE CHANGE CLIMATE WITHTROPICALANDSUBTROPICAL COPE PLANNING TO EnricoPonte,ElenaCristofori Maurizio Tiepolo, Maurizio Tiepolo, Enrico Ponte, Elena Cristofori (Eds.) During the last decade, many local governments have launched initiatives to reduce CO2 emissions and the potential impact of hydro-climatic disasters. Nonetheless, PLANNING TO COPE today barely 11% of subtropical and tropical cities with over 100,000 inhabitants have a climate plan. Often this tool neither issues from an analysis of climate change or hydro climatic risks, nor does it provide an adequate depth of detail WITH TROPICAL for the identified measures (cost, funding mode, implementation), nor a sound monitoring-evaluation device. This book aims to improve the quality of climate planning by providing 19 examples AND SUBTROPICAL of analysis and assessments in eleven countries. It is intended for local operators in the fields of climate, hydro-climatic risks, physical planning, besides researchers and students of these subjects. -

Sketch-Map Illustrating the Special Agreement Seising the International Court of Justice

- 96 - Sketch-map illustrating the Special Agreement seising the International Court of Justice Tillabéry Tripoint a and b: sectors agreed between the Parties 1 and 2: sectors disputed by the Parties 1: Téra sector 2: Say sector Tripoint: meeting point of Tillabéry, Say and Dori cercles This sketch-map is for illustrative purposes only 4 February 2011 - 97 - 7.6. The area is characterized by the presence of abundant wildlife. Its southern part includes one of the most important wildlife reserves in West Africa: the Niger W Regional Park 291 , which covers 1 million hectares on the territories of Niger, Burkina Faso and Benin. Outside the area of the park, towards the River Sirba, herds of elephant, buffalo and warthog can be met with, as well as groups of lion, hyena and leopard, which makes the conduct of human activity problematic in the area. The region’s watercourses and pools were long infested with tsetse flies, causing blindness among humans and animals. This parasite was eradicated several decades ago. But previously, the presence of tsetse fly and poisonous snakes resulted in the relocation of many villages, or even their disappearance. 7.7. In human terms, the Say/Fada region is lightly populated. It is subject to constant regional transhumance. This is of three kinds: major transhumance, which consists of movements over very long distances, generally practiced by the Bororo and related Peulhs; minor transhumance, a movement over short and medium distances, generally carried out in order to exploit the pastureland beside rivers and pools; commercial transhumance, involving small flocks, for the purpose of increasing milk production and taking advantage of the pasturage provided by fallow croplands. -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

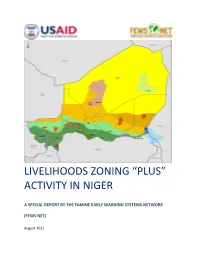

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt .....................................................................................................................