The Criminalization of States the Relationship Between States and Organized Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

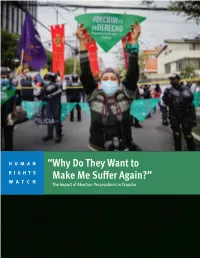

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

Ecuador-Background.Pdf

Drug law reform in Latin America Working document, Chapter Ecuador A Short History of the Effects of Drug Policy and Its Implementation on Ecuador’s Prison System Sandra G. Edwards May 2010 1 A Short History of Ecuador’s Drug Legislation and the Impact on its Prison Population by Sandra G. Edwards Ecuador, a small country on the Pacific Coast of South America, has never been known as a significant producer or trafficker of illicit drugs; nor has the country ever experienced the social convulsions that can result from high levels of drug abuse or the existence of a dynamic domestic drug market.1 While Ecuador has become an important transit country for illicit drugs and precursor chemicals and for money laundering, the illicit drug trade has not been considered a major threat to the country’s national security.2 However, for nearly two decades, Ecuador has not only had one of the most draconian drug laws in Latin America, U.S. economic assistance to Ecuador has consistently prioritized drug control funding to its security forces. Ecuador’s drug law, Law 108, The Law on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, was not developed based on the reality on the ground, but rather was the result of international pressures and domestic politics. It is an extremely punitive law, resulting in sentences disproportionate to the of- fense, contradicting due process guarantees and violating the constitutional rights of the accused. Its focus on enforcement and the presence of U.S. pressure meant that the success of Ecuador’s drug policies was measured by how many individuals were in prison on drug charges. -

Political Culture of Democracy in Ecuador, 2010 Democratic

Political Culture of Democracy in Ecuador, 2010 Democratic Consolidation in the Americas in Hard Times By: Juan Carlos Donoso, Ph.D. Daniel Montalvo, Ph.D. Diana Orcés, Ph.D. Mitchell A. Seligson, Ph.D. Scientific Coordinator and Editor of the Series Vanderbilt University This study was done with support from the Program in Democracy and Governance of the United States Agency for International Development. The opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the point of view of the United States Agency for International Development. March, 2011 Political Culture of Democracy in Ecuador, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................................................................................... V LIST OF TABLES .....................................................................................................................................................................XI PREFACE ...............................................................................................................................................................................XIII PROLOGUE: BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY............................................................................................................... XV Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................................xxii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................XXV -

Download Ecuador-En.Pdf

A Short History of Ecuador’s Drug Legislation and the Impact on its Prison Population by Sandra G. Edwards Ecuador was never a significant center of production or traffic of illicit drugs; nor has it ever experienced the social convulsions that can result from the existence of a dynamic domestic drug market. While Ecuador has become an important transit country for illicit drugs and precursor chemicals and for money laundering, the illicit drug trade has not been perceived as a major threat to the country’s national security. However, for nearly two decades, Ecuador has had one of the most draconian drug laws in Latin America. Ecuador’s current drug law, The Law on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, better known as 108, was not developed based on the reality on the ground, but rather was the result of international pressures and domestic politics. It is an extremely punitive law, resulting in sentences disproportionate to the offense, contradicting due process guarantees and violating the constitutional rights of the accused. Its focus on enforcement and the presence of U.S. pressure meant that the success of Ecuador’s drug policies was measured by how many individuals were in prison on drug charges. This resulted in major prison over-crowding and a worsening of prison conditions. This paper analyzes the direct connections between Law 108 and Ecuador’s worsening prison conditions up until the time of the present government. Although the law is still in force, the Correa administration is the first to analyze the law’s ramifications, define the problems within the country’s prisons and develop proposals for legal and institutional reforms related to both drugs and prisons. -

Criminalité Urbaine En Equateur : Trois Essais Sur Les Rôles Des Inégalités Économiques, La Taille Des Villes Et Les Émotions Andrea Carolina Aguirre Sanchez

Criminalité urbaine en Equateur : trois essais sur les rôles des inégalités économiques, la taille des villes et les émotions Andrea Carolina Aguirre Sanchez To cite this version: Andrea Carolina Aguirre Sanchez. Criminalité urbaine en Equateur : trois essais sur les rôles des in- égalités économiques, la taille des villes et les émotions. Economics and Finance. Université de Lyon; Faculte latinoamericaine de sciences sociales. Programa Ecuador, 2018. English. NNT : 2018LY- SES051. tel-02068954 HAL Id: tel-02068954 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02068954 Submitted on 15 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N°d’ordre NNT : 2018LYSES051 UNIVERSITÉ JEAN MONNET SAINT-ÉTIENNE Groupe d’Analyse et de Théorie Économique Lyon Saint-Étienne, UMR 5824 Université de Lyon École Doctorale de Sciences Économiques et de Gestion 486 Urban Crime in Ecuador: Three essays on the role of economic inequalities, population density and emotions THÈSE DE DOCTORAT EN SCIENCES ÉCONOMIQUES Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Andrea Carolina AGUIRRE SÁNCHEZ Devant le jury composé de: Fabien CANDAU, Professeur, Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour (Rapporteur). Nelly EXBRAYAT, Maître des Conférences HDR, Université de Saint-Étienne (Directrice de thèse). -

Dissertation Andrea Romo.Pdf

Gender biased police misbehaviour. An analysis of deviant police practices and female offenders' experiences in Ecuador (1979-2010) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Andrea Romo Pérez Berlin im September 2018 1. Gutachter/in: Prof. Dr. Debora Gerstenberger Freie Universität Berlin Lateinamerika Institut (LAI) 2. Gutachter: Prof.Dr. Markus Michael Müller Freie Universität Berlin Lateinamerika Institut (LAI) Tag der Disputation: 05.02.2019 Acknowledgments I would like to thank God for allowing me to conduct this exciting and important research project. I would also like to thank a number of people special to me because, without their help and guidance, the completion of this dissertation would have not been possible. Pro- fessors Debora Gerstenberger and Markus Müller: thank you for your support during this time. I couldn’t have asked for better supervisors. I appreciate every second of your time as well as everything you have done for me and this project throughout these four years. Debora you are an extraordinary human being. I also want to thank Dr. Teresa Orozco for the always kind and amazing help you have given me during this time. Thanks Dr. Rocio Vera for the advice you gave me throughout my studies and your support as a friend. To all my friends in Germany and Ecuador I want to thank for their support, time, company and loyalty. Having you in my life gave me strength and the energy to continue every day. I love you. Finally thank you to my family: Sister, mom, uncle and aunt. -

2001-Audit.Pdf

DEMOCRACY AUDIT: ECUADOR 2001 BY MITCHELL A. SELIGSON WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF AGUSTÍN GRIJALVA UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LATIN AMERICAN PUBLIC OPINION PROJECT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PITTSBURGH, PA 15260 [email protected] JULY 31, 2003 SUPPORTED BY A GRANT FROM THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (511-330-4265) Democracy Audit: Ecuador 2001 1 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The survey reported on in these pages is the largest, most comprehensive effort to systematically measure the political culture of Ecuador. As such, it required a great deal of effort by many parties, and we would like to thank a number of them here. The sample design, field work and data entry for the project were carried out by CEDATOS, the Gallup International affiliate in Ecuador, ably led by its director, Dr. Polibio Córdova. We have been deeply impressed by the professionalism, skill and care demonstrated by that organization at every step of the way. The pre-testing of the questionnaire and the supervision of interviewer training was carried out by Dr. Orlando Pérez of the University of Central Michigan. With Orlando’s expert assistance we were able to move through what turned out to be 19 distinct revisions of the instrument and to produce a polished final product. At the University of Pittsburgh, we owe a great deal to Melanie Weissberger and Rocco Belmonte, our two work-study assistants who helped track down citations and struggle with the formatting of the final document. Mary Malone ably translated key components of the study. Michelle Pupich of the Department of Political Science ably handled all of the financial and logistical details of the project.