Moving Towards Markets: Cash, Commodification and Conflict in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an Extension of the Deadline For

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of Anti-personnel Mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 of the convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction Submitted at the 18th Meeting of the State Parties Submitted to the Chair of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Date 31 March 2020 Prepared for State Party: South Sudan Contact Person : Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch Position: Chairperson, NMAA Phone : (211)921651088 Email : [email protected] 1 | Page Contents Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 II. Detailed Narrative 8 1 Introduction 8 2 Origin of the Article 5 implementation challenge 8 3 Nature and extent of progress made: Decisions and Recommendations of States Parties 9 4 Nature and extent of progress made: quantitative aspects 9 5 Complications and challenges 16 6 Nature and extent of progress made: qualitative aspects 18 7 Efforts undertaken to ensure the effective exclusion of civilians from mined areas 21 # Anti-Tank mines removed and destroyed 24 # Items of UXO removed and destroyed 24 8 Mine Accidents 25 9 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: quantitative aspects 27 10 The Disaggregation of Current Contamination 30 11 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: qualitative aspects 41 12 Circumstances that impeded compliance during previous extension period 43 12.1 Humanitarian, economic, social and environmental implications of the -

Land Tenure Issues in Southern Sudan: Key Findings and Recommendations for Southern Sudan Land Policy

LAND TENURE ISSUES IN SOUTHERN SUDAN: KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SOUTHERN SUDAN LAND POLICY DECEMBER 2010 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Tetra Tech ARD. LAND TENURE ISSUES IN SOUTHERN SUDAN: KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SOUTHERN SUDAN LAND POLICY THE RESULTS OF A RESEARCH COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE SUDAN PROPERTY RIGHTS PROGRAM AND THE NILE INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES DECEMBER 2010 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acknowledgements Page i Scoping Paper Section A Sibrino Barnaba Forojalla and Kennedy Crispo Galla Jurisdiction of GOSS, State, County, and Customary Authorities over Land Section B Administration, Planning, and Allocation: Juba County, Central Equatoria State Lomoro Robert Bullen Land Tenure and Property Rights in Southern Sudan: A Case Study of Section C Informal Settlements in Juba Gabriella McMichael Customary Authority and Traditional Authority in Southern Sudan: A Case Study Section D of Juba County Wani Mathias Jumi Conflict Over Resources Among Rural Communities in Southern Sudan Section E Andrew Athiba Synthesis Paper Section F Sibrino Barnaba Forojalla and Kennedy Crispo Galla ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The USAID Sudan Property Rights Program has supported the Southern Sudan Land Commission in its efforts to undertake consultation and research on land tenure and property rights issues; the findings of these initiatives were used to draft a land policy that is meant to be both legitimate and relevant to the needs of Southern Sudanese citizens and legal rights-holders. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 March 8, 2019

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 MARCH 8, 2019 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Insecurity in Yei results in unknown number of civilian deaths, prevents 15,000 5% 7% 20% people from receiving aid 7.1 million 7% Estimated People in South Health actors continue EVD awareness Sudan Requiring Humanitarian 10% and screening activities Assistance 19% 2019 Humanitarian Response Plan – WFP conducts first road delivery to 15% December 2018 central Unity 17% Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Health (17%) 6.5 million FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE Nutrition (15%) Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) February 2019 Shelter & Settlements (5%) USAID/FFP $398,226,647 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 1.9 million USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $624,967,8824 Estimated IDPs in BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE South Sudan SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 UN – January 31, 2019 84% 9% 5% U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,756,094,855 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE 191,238 Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases UNMISS – March 4, 2019 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Ongoing violence between Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GoRSS) and opposition forces near Central Equatoria State’s Yei area has displaced an estimated 2.3 million 7,400 people to Yei town since December and is preventing relief agencies from reaching Estimated Refugees and Asylum more than 15,000 additional people seeking safety outside of Yei, the UN reports. -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES .................................................................................................................................................................. -

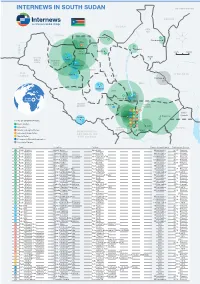

Internews in South Sudan Map Updated May 2020

INTERNEWS IN SOUTH SUDAN MAP UPDATED MAY 2020 SUDAN SUDAN UPPER NILE SUDAN Jamjang 11 3 Gendrassa Abyei 1 2 UNITY 34 Malakal 40 Bentiu 0 km 100 km Turalei 7 SUDAN 4 5 Nasir WESTERN Aweil BAHR EL NORTHERN GHAZAL BAHR EL 32 GHAZAL Kwajok WARRAP D.R. 41 Wau ETHIOPIA CONGO 42 Leer Pochala 36 JONGLEI 37 38 Rumbek LAKES 8 9 10 6 Bor South Awerial Sudan WESTERN Mundri EASTERN EQUATORIA 35 EQUATORIA 12 18 24 30 13 19 25 Ilemi- Kapoeta Dreieck Yambio Juba 14 20 26 15 21 27 31 TYPES OF ORGANIZATIONS 43 16 22 28 Radio Station 17 23 29 Torit Repeaters CENTRAL KENYA Media Training Institution EQUATORIA Magwi DEMOCRATIC 33 Advocacy Organization REPUBLIC OF Media Outlet THE CONGO Community-Based Organization UGANDA Associate Partner Type Location Partner Reach (if applicable) Partnership Active 1 Radio Station Abyei, Agok Abyei FM 60 km radius 2015 - Present 3 Radio Station Jamjang, Unity Jamjang FM 60 km radius 2016 - Pesent 4 Radio Station Aweil, Northern Bahr el Ghazal Akol Yam 91.0FM 150 km radius 2017 - Present 6 Radio Station Awerial, Lakes Mingkaman 100FM 150 km radius 2014 - Present 7 Radio Station Bentiu, Unity Kondial FM 30 km radius 2018 - Present 8 Radio Station Bor, Jonglei Radio Jonglei 50 km radius 2018 11 Radio Station Gendrassa, Upper Nile Radio Salam 30 km radius 2019 - Present 19 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Radio Bakhita 100 km radius 2015-2016 23 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Advance Youth Radio 50 km radius 2019 - Present 26 Radio Station Juba, Central Equatoria Eye Radio 60 km radius 2014 - Present 28 Radio Station -

Tragedy, Ritual, and Power in Nilotic Regicide

Tragedy, Ritual and Power in Nilotic Regicide: The regicidal dramas of the Eastern Nilotes of Sudan in Comparative Perspective1 Simon Simonse Introduction Regicide as an aspect of early kingship is a central issue in the anthropological debate on the origin of the state and the symbolism of kingship. By a historical coincidence the kingship of the Nilotic Shilluk has played a key role in this debate which was dominated by the ideas of James Frazer, as set out in the first (The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings), the third (The Dying God) and the sixth part (The Scapegoat) of The Golden Bough (1913). The fact that the Shilluk king was killed before he could die a natural death was crucial to Frazer’s interpretation of early kingship. Frazer equated the king with a dying god who though his death regenerates the forces of nature. This ‘divine kingship’ was an evolutionary step forward compared to ‘magical kingship’ where the power of the king is legitimated by his claim to control the natural processes on which human communities depend. Frazer’s interpretation of kingship was opposed by a post-war generation of anthropologists who were interested in the empirical study of kingship as a political system and who treated the ritual and symbolic aspects of kingship as a secondary dimension of kingship more difficult to penetrate by the methodology of structural-functional analysis. The reality of the practice of regicide that was so central to Frazer’s interpretations of kingship was put in doubt (Evans-Pritchard, 1948). The ongoing practice by mostly Eastern Nilotic communities of killing Rainmakers when they failed to make rain – noted by Frazer in The Golden Bough (1913, Part 1, Vol. -

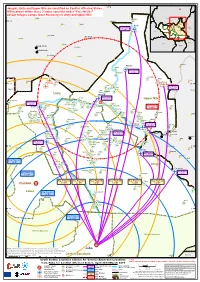

Unity Jonglei Upper Nile Lakes Central Equatoria Rumbek Juba

Jonglei, Unity and Upper Ni3l0e° Eare identified as Conflict Affected States. 32° E 34° E Khartoum All locations within these 3 states consider under "Free-to-Use" except refugee camps (Cost Recovery) in Unity and Upper Nile Dilling Gerger Sudan 12° N Alakafaria 12° N Upper Dalami Rashad Nile Renk Ab yei Unity El Roseires Avg. Payload: Ed DamEthaiozpiian 5.2 MT South Sudan Jonglei Wadakona CAR Umm Heitan Abu Jibaiha Lagawa Kenya DRC Heiban Kadugli (North) Uganda Sudan Kadugli (South) Umm Dorain Kologi Wirni Kurmuk Paloich Melut Avg. Payload: Athidway 5.2 MT Yida Jemaam Kaya Asosa Higlig Ajuong Pariang Thok Yusuf Doro 10° N Batil Bunj/Maban 10° N Oriny Kodok Gendrassa Rom Avg. Payload: Lul 5.2 MT Abyei Akoka Bambesi Wau Nyingaro Shaluk Unity Malakal Tonga Avg. Payload: 5.2 MT Upper Nile Abiemnhom Juaibor New Kaldak Avg. Payload: Rubkona Pigi Fangak Baliet 5.2 MT Kuernyang Kurwai Kamel Mayom Mayom Khorfulus Wun-Gak Avg. Payload: Dajo Bentiu Atar 1.3 MT Guit Paguer Old Abwong Fangak Riang Mankien Wang-Kay Kadet Wunrok Chuil Kiech Mathiang Nhialdiu Kon Gidami Wicok Ngop Kuach Juong Boaw Thow Toic Kuacdeng Mading Gaireng Turkej Pagil Gum Ulang Wathjak NassAvegr. Payload: Koch Menime Maiwut Pultruk Nyangore 5.2 MT Kandak Mandeng Mir Mir Haat Pagak Pading Nyambor Lankien Jikmir Mogok Makak Pagak Jiech Avg. Payload: Jikou Dablual 5.2 MT Metar Leer Malwal-Gakhoth Nyenyang Kowerneng Wai Gorway Gambela Nyanepol Mayendit Adok Motot Mwot Tot Waat Itang Ayod Avg. Payload: Pathai Walgak Pagiel Pieri Wanding 5.2 MT Torwar Kotdalok 8° N Madol Yuai Ethiopia 8° N Warrap Abobo Duk Akobo Shentewa Nyal Ayueldit Fadiat Pajut Avg. -

Central Equatoria State Map

" ") 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E " Padak/baidit Central Equatoria State Map Lakes ") Anyidi Atiit " Attit Bor Jonglei Akojan Awerial Mimi " Mvolo Rein " Attir N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 Bengeya 0 ° ° 6 Melekwich 6 Buron Tali Marlango " Jabor Bari Umbolo Tokot Verlingai Tellang Gillut Yebisak Jakari Buring Tombi Yeri Mirda Mandari Moggi Buka " Gboerr Shogle Tur Baro Gwojo-adung Gaya Mogutt Bori Mejiki Kulwo Rumih Nyale Gutetian Jarrah Maralinn Makur Tiarki Gigging Vora Malari Maleit Bita Badai Gemmaiza Parilli TERKEKA Bojo-ajut Tindalo Mori Jua Baringa Tuga Gobo Wani Poko Bologna Bokuna Pagar Settlements Loriangwara Tankariat Tukara Mandari Pom Toe Kursomba Gali Type Langni Rejar Amadi Lopore Wala Langkokai Bulu Koli " Loduk Golo ") State Capitals Kumaring Rego Terkeka Logono ") Wit ") Wanyang Larger Towns Western Equatoria Minga Gabir Magara Juban Western Equatoria Rambo Jelli Amardi " Biyara Kworijik Towns ") Mundri Lui Badigeru Swamp " Legeri Simsima Big Villages Bala Pool Small Villages Mangalla Buko " Fajelu Tijor Gabur Main Road Network Rokon Rombe Lako " Man Karo Jokoki Lado Koda County Boundaries Wulikare Nija Ludo Kenyi Logo Luala Lado N N " El Iqlim Al Istiwa'i Tibari " 0 State Boundaries 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 5 Gori 5 Ilibari River Nyigera Gamichi National Boundary Mugiri Nyara Indura Pitia Gondokoro Gworolorongo Roja Kenyi Tambur International Boundaries Nyangwara Lukudu Juba River Wanga Singi Perang Mogiri Jongwa Lokoko ") Chamba Chaka Gumba Mandubulu Kamarok Lokoiya Mendopolo Kimangoro Tokiman Tobaipapwa Katatabi Lekilla Jeraputa Lokuta Rejaf -

CEDAT Spotlight: South Sudan and Adjacent Areas (1998 -2012)

Complex Emergency Database CEDAT May 2013 CEDAT spotlight: South Sudan and adjacent areas (1998 -2012) White Nile Sinnar CE-DAT coverage West Kordofan Surveys on South Kordofan Blue Nile South Darfur - residents 173 - IDPs 62 Upper Nile Abyei - refugees 11 North Bahr-al-Ghazal Unity - mixed 154 West Bahr-al-Ghazal Warab Total surveys 400 4 Jonglei DeLinitions of indicators and pop- Lakes ulation groups and further tech- Kilometers nical information can be found on 0100 200 400 West Equatoria www.cedat.be . Central Equatoria Eastern Equatoria Administrative unit: district historical data available in CE-DAT (1998-2009) recent data available in CE-DAT (2010-2012) heavily conflict affected (ACLED reports at least 5 event since 2010) Median (minimum - maximum) values: 2010 -2012 (n=71) Acute malnutrition (%) Mortality (deaths/10,000/day) Vaccination (%) Globa l Severe Crude Child Measles North Bahr -El-Ghazal 23.5 4.9 0.41 0.64 11.6 (18.4 - 25.7) (2.7 - 6) (0.13 - 0.97) (0 - 0.98) Jonglei 15.2 5 0.64 0.71 57.5 (13.7 - 45.7) (2.1 - 15.5) (0.03 - 2.40) (0.03 - 5.14) (29.6 - 92) Upper Nile 28.3 7.8 0.91 1.28 82 (14.4 - 39.8) (3.9 - 13.4) (0.76 – 1.75) (0.75 - 4.19) (78.3 - 85.7) Unity 0.97 1.68 NA NA NA (0.73 - 1.95) (1.19 - 3.98) Warab 22.4 4.6 0.42 1.19 58.4 (12.1 - 25.2) (0.9 - 5.9) (0.35 - 1. -

Central Equatoria State

Central Equatoria State Map 30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E Ngwer Falabai Ngop Fagiel Korikori Wulu Paker Gumro Unagok Alel Lual Ashandit Kulu Chundit Bunagok Bor Makuac Eassi Dekada Yirol West Atiit Deng Shol Pengko Jerweng )" Brong Anyidi Wulu Pul Anyuol Anuol Rokon Macdit Minikolome Malangya Khalil Nyadask Awerial Wurrier Tukls Lake Nyiropo Latolot Kondoagoi Anyat Awan Wako Lakes " Nyiel Bahr El Girin Awerial Bor South Mvolo Pwora Dor Jonglei " Minkamman Jalango Guar Aliab Aliab N Dogoba Kila Malek N " " 0 Dorri 0 ' Ambo Wun Abiyei ' 0 Bengeya Golo Dijeyr Pariak Pariak 0 ° Wun Thou ° 6 River Tapari 6 Gira Domeri Melekwich Wun Chwei Mangi Panabang Mvolo Koalikiri Tali Melwel Latuk Lesi " Jabor Bari Dakada Awiri Wasi Verlingai Tellang Banwar Dari Ndia Azai Jakari Mirda Tombi Duboro Yeri Delinoi Mulinda Mandari Teri Tur Gwojo-Adung Azai Kulundulu Kasiko Gaya Gutetian Tiarki Bori Kulwo Jarrah Maralinn Bogora Gigging Bogori Vora Bita Gemmaiza Lakamadi Tindalo Bojo-Ajut Terekeka Gobo Gabir Bokuna Poko Gulu Rushi Duwwo Wani Mika Pagar Bitti Tukara Abdulla Mbara Magiri Lamindo Pom Lopore Wala Gali Kpakpawiya Kederu Kediba Onayo Amadi Bulu Koli Ire " Paya Wandi Riku Doso Wito Rego Logono Terekeka Kemande Mariba Gabir Wit Magara )" Movo Minga Juban Western Equatoria Gullu Mundri Amardi Rambo Lui Gabat Badigeru Swamp )" " Wiro River Meri Mundri East Kotobi Lanyi Bala Pool Lapon Yalo Mangalla Mundri West Buko " Madi Buaji Naramoa Karika Landigwa Laporu Rokon Tijor Gunba " Mulai Kalala Bunduqiyah Bahr Olo Nidri Wulikare Bundukki Jambo Jalang Luala N -

The Burst and the Cut Stomach -The Metabolism of Violence and Order

The Burst and the Cut Stomach . -The Metabolism of Violence and Order 1n Nilotic Kingship- SIMON SIMONSE Universit;' of Leiden An interpretation is offered of two contrasting Nilotic customs relating to the stomach of a king who has just died: the cutting of the stomach of a king who has been killed by his subjects for causing drought and the practice of some Bari speaking peoples of allowing the stomach of the king, who has died a natural death, to bloat and burst. The case material on the cutting of the stomach is taken from nineteenth cen tury accounts by travellers and a missionary concerning two cases of regicide among the Bari and from the study of the murder of the Pari queen in 1984 by the an thropologist Eisei Kurimoto. In a first round of interpretation it is argued that the relevant property of the stomach in this context, as well as in other Nilotic sacrificial ritual, is its capacity to turn a mass of undifferentiated substance into something valued and desirable. In a sec ond round we demonstrate that the stomach-metaphor is used to make sense of the socio-political impact of the king on the conflicts in his realm and, closely interwined with that, of his cosmic impact on the weather. To understand why the king's metabolism plays such an important role at the moment of his death we turn to the theory of the victimary origins of kingship developed by Rene Girard. Since the death of the king is a powerful lever for achieving social unity and cosmic harmony, his peo ple should leave nothing to chance when he dies, especially with regards to the organ most closely associated with his powers to dissolve conflicts and bring peace and rain.