State-Building and Land Conflict in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

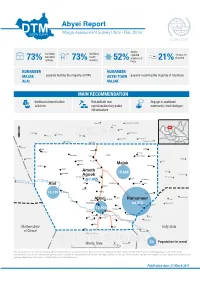

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

![Visit to Terekeka [Oct 2020]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9639/visit-to-terekeka-oct-2020-339639.webp)

Visit to Terekeka [Oct 2020]

Visit to Terekeka and St Stephen’s School, South Sudan – 17th – 18th March 2020 Report by Mike Quinlan Introduction Following my participation in a SOMA (Sharing of Ministries Abroad) Mission to the Internal Province of Jonglei from 7th to 16th March, I was able to make a short visit to Terekeka and to St Stephen’s School escorted by the Bishop of Terekeka, Rt Rev Paul Moji Fajala. Bp Paul met me at my hotel in Juba and drove me to Terekeka on the morning of Tuesday 17th March. We visited St Stephen’s School and I also saw some of the other sights of Terekeka (mainly boats on the bank of the Nile). Bp Paul also took me to see his house in Terekeka. After a night at a comfortable hotel, which had electricity and a fan in the evening, Bp Paul drove me back to Juba on the morning of Wednesday 18th March. I was privileged to be taken to meet the Primate of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan (ECSS), Most Rev Justin Badi Arama at his office. ABp Justin is also the chair of SOMA’s International Council. Bp Paul also took me to his house in Juba, where I met his wife, Edina, and had lunch before he took me to the airport to catch my flight back to UK. Terekeka is a small town about 75km north of Juba on the west bank of the White Nile. It takes about two and a half hours to drive there from Juba on a dirt road that becomes very difficult during the rainy season. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

Population Mobility Mapping (Pmm) South Sudan: Ebola Virus Disease (Evd) Preparedness

POPULATION MOBILITY MAPPING (PMM) SOUTH SUDAN: EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE (EVD) PREPAREDNESS CONTEXT The 10th EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is still ongoing, with a total of 3,428 EVD cases reported as of 2 February 2020, including 3,305 confirmed and 118 probable cases. A total of 2,250 deaths have been reported, with a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 65.6%. Although the rate of new cases in DRC has decreased and stabilized, two health zones reported 25 new confirmed cases within the 21-day period from 13 January to 2 February 2019: Beni (n=18) and Mabalako (n=30).1 The EVD outbreak in DRC is the 2nd largest in history and is affecting the north-eastern provinces of the country, which border Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan. South Sudan, labeled a 'priority 1' preparedness country, has continued to scale up preparedeness efforts since the outbreak was confirmed in Kasese district in South Western Uganda on 11 June 2019 and in Ariwara, DRC (70km from the South Sudan border) on 30 June 2019. South Sudan remains at risk while there is active transmission in DRC, due to cross-border population movements and a weak health system. To support South Sudan’s Ministry of Health and other partners in their planning for EVD preparedness, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has applied its Population Mobility Mapping (PMM) approach to inform the prioritization of locations for preparedness activities. Aim and Objectives The aim of PMM in South Sudan is to inform the 2020 EVD National Preparedness Plan by providing partners with relevant information on population mobility and cross-border movements. -

Local Needs and Agency Conflict: a Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 11, Issue 1 | Fall 2009 Local Needs and Agency Conflict: A Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan RANDALL FEGLEY Abstract: During Southern Sudan’s second period of civil war, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provided almost all of the region’s public services and greatly influenced local administration. Refugee movements, inadequate infrastructures, food shortages, accountability issues, disputes and other difficulties overwhelmed both the agencies and newly developed civil authorities. Blurred distinctions between political and humanitarian activities resulted, as demonstrated in a controversy surrounding a 2004 distribution of relief food in Central Equatoria State. Based on analysis of documents, correspondence and interviews, this case study of Kajo Keji reveals many of the challenges posed by NGO activity in Southern Sudan and other countries emerging from long-term instability. Given recurrent criticisms of NGOs in war-torn areas of Africa, agency operations must be appropriately geared to affected populations and scrutinized by governments, donors, recipients and the media. A Critique of NGO Operations Once seen as unquestionably noble, humanitarian agencies have been subject to much criticism in the last 30 years.1 This has been particularly evident in the Horn of Africa. Drawing on experience in Ethiopia, Hancock depicted agencies as bureaucracies more intent on keeping themselves going than helping the poor.2 Noting that aid often allowed despots to maintain power, enrich themselves and escape responsibility, he criticized their tendency for big, wasteful projects using expensive experts who bypass local concerns and wisdom and do not speak local languages. He accused their personnel of being lazy, over-paid, under-educated and living in luxury amid their impoverished clients. -

South Sudan Rapid Response Ebola 2019

RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS YEAR: 2019 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS SOUTH SUDAN RAPID RESPONSE EBOLA 2019 19-RR-SSD-33820 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR ALAIN NOUDÉHOU REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. 10 October 2019 The AAR took place on 10 October 2019, with the participation of WHO, UNICEF, IOM, WFP, and the Ebola Secretariat (EVD Secretariat). b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report on the Yes No use of CERF funds was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team. The report was not discussed within the Humanitarian Country Team due to time constraints; however, they received a draft of the completed report for their review and comment as of the 25 October 2019. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant Yes No government counterparts)? The final version of the RC/HC report was shared with CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, as well as with cluster coordinators and the EVD Secretariat, as of 16 October 2019. 2 PART I Strategic Statement by the Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator South Sudan is considered to be one of the countries neighbouring the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at highest risk of Ebola importation and transmission. Thanks to the allocation of USD $2.1 million from the Central Emergency Relief Fund Ebola preparedness in South Sudan, including the capacity to detect and respond to Ebola, has been strengthened. -

Boating on the Nile

United Nations Mission September 2010 InSUDAN Boating on the Nile Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 8 August: Meeting with Minister of Humanitarian Affairs Mutrif Siddiq, Joint Special Representative for Darfur 3 Special Focus: Transport Ibrahim Gambari expressed regrets on behalf of the • On every corner Diary African Union-UN Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) over • Boating on the Nile recent events in Kalma and Hamadiya internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in • Once a lifeline South Darfur and their possible negative impacts on the future of the peace process. • Keeping roads open • Filling southern skies 9 August: Blue Nile State members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and National Congress Party (NCP) formed a six-member parliamentary committee charged with raising awareness about popular consultations on Comprehensive Peace Agreement 10 Photo gallery implementation in the state. The Sufi way 10 August: The SPLM and NCP began pre-referendum talks on wealth and power-sharing, 12 Profile demarcating the border, defining citizenship and sharing the Nile waters in preparation for the Knowledge as food southern self-determination vote, scheduled for 9 January 2011. 14 August: Two Jordanian police advisors with UNAMID were abducted in Nyala, Southern Darfur, 13 Environment as they were walking to a UNAMID transport dispatch point 100 meters from their residence. Reclaiming the trees Three days later the two police advisors were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. 14 Communications 16 August: Members of the Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission elected a nine-member The voice of Miraya steering committee to oversee its activities as the region approaches the self-determination referendum three days later the two police advisor were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. -

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an Extension of the Deadline For

The Republic of South Sudan Request for an extension of the deadline for completing the destruction of Anti-personnel Mines in mined areas in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 1 of the convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction Submitted at the 18th Meeting of the State Parties Submitted to the Chair of the Committee on Article 5 Implementation Date 31 March 2020 Prepared for State Party: South Sudan Contact Person : Jurkuch Barach Jurkuch Position: Chairperson, NMAA Phone : (211)921651088 Email : [email protected] 1 | Page Contents Abbreviations 3 I. Executive Summary 4 II. Detailed Narrative 8 1 Introduction 8 2 Origin of the Article 5 implementation challenge 8 3 Nature and extent of progress made: Decisions and Recommendations of States Parties 9 4 Nature and extent of progress made: quantitative aspects 9 5 Complications and challenges 16 6 Nature and extent of progress made: qualitative aspects 18 7 Efforts undertaken to ensure the effective exclusion of civilians from mined areas 21 # Anti-Tank mines removed and destroyed 24 # Items of UXO removed and destroyed 24 8 Mine Accidents 25 9 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: quantitative aspects 27 10 The Disaggregation of Current Contamination 30 11 Nature and extent of the remaining Article 5 challenge: qualitative aspects 41 12 Circumstances that impeded compliance during previous extension period 43 12.1 Humanitarian, economic, social and environmental implications of the -

Frontlines September/October 2011

FRONTLINES WWW.USAID.GOV SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 TWO SUDANS THE SEPARATION OF AFRICA’S LARGEST COUNTRY AND THE ROAD AHEAD > A GLOBAL EDUCATION FOOTPRINT TAKES SHAPE > EGYPT SHAKES UP THE CLASSROOM > Q&A WITH REP. NITA LOWEY Sudan & South Sudan/Education Edition INSIGHTS From Administrator Dr. Rajiv Shah A few weeks before South Sudan’s skills, making it more likely they will day of independence, I had the oppor- eventually drop out. tunity to visit the region and meet a These failures leave developing na- HE WORLD welcomed its group of children who were learning tions without the human and social newest nation when South English and math in a USAID-supported capital needed to advance and sustain Sudan officially gained its primary education program. The stu- development. They deprive too many inde pendence on July 9. After dents ranged in ages from 4 to 14. individuals of the skills they need as Tover two decades of war and suffering, Many of the older students have lived productive members of their commu- a peace agree ment between north and through a period of displacement, vio- nities and providers for their families. south Sudan paved the way for South lence, and trauma. This was likely the Across the world, our education pro- Sudanese to fulfill their dreams of self- very first opportunity they had to re- grams emphasize a special focus on determination. The United States played ceive even a basic education. disadvantaged groups such as women an important role in helping make this When you see American taxpayer and girls and those living in remote moment possible, and today we remain money being effectively used to provide areas. -

National Education Statistics

2016 NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FEBRUARY 2017 www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education & Instruction 2017 Photo Courtesy of UNICEF This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. The map used in this document is not the official maps of the Republic of South Sudan and are for illustrative purposes only. This publication has been produced with financial assistance from the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and technical assistance from Altai Consulting. Soft copies of the complete National and State Education Statistic Booklets, along with the EMIS baseline list of schools and related documents, can be accessed and downloaded at: www.southsudanemis.org. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director of Planning and Budgeting / MoGEI [email protected] Giir Mabior Cyerdit / EMIS Manager / MoGEI [email protected] Data & Statistics Unit / MoGEI [email protected] Nor Shirin Md. Mokhtar / Chief of Education / UNICEF [email protected] Akshay Sinha / Education Officer / UNICEF [email protected] Daniel Skillings / Project Director / Altai Consulting [email protected] Philibert de Mercey / Senior Methodologist / Altai Consulting [email protected] FOREWORD On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am delighted to present The National Education Statistics Booklet, 2016, of the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). It is the 9th in a series of publications initiated in 2006, with only one interruption in 2014, a significant achievement for a new nation like South Sudan. The purpose of the booklet is to provide a detailed compilation of statistical information covering key indicators of South Sudan’s education sector, from ECDE to Higher Education.