A Modular Approach to Evidentiality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/64d102q5 Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 5(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Davies, William D Publication Date 1994-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L451005171 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California English Dative Alternation and Evidence for a Thematic Strategy in Adult SLA William D. Davies University of Iowa INTRODUCTION A body of recent work in second language acquisition is concerned with applying constructs from Chomsky's conception of Universal Grammar in both constructing an overall theory of SLA and explaining various phenomena in L2 learners (e.g., Flynn, 1984, 1987; Hilles, 1986; Phinney, 1987; White, 1985a, 1985b; papers in Flynn and O'Neil, 1988). A key linguistic construct that has received relatively little attention in SLA research is thematic roles—notions such as AGENT, THEME, GOAL, LOCATION, SOURCE, and others that are believed to contribute to semantic encoding and decoding. Although thematic roles (alternatively, thematic relations, semantic roles, case roles, 9-roles) have long been part of modem linguistic theory (cf. Gruber, 1965; Fillmore, 1968; Jackendoff, 1972), they have enjoyed increased popularity in the recent linguistic literature owing in part to their central role in Chomsky's (1981) government and binding (GB) theory, as embodied in the G-Criterion.^ Various formulations of the 9-Criterion have been proposed, but the simple formulation in (1) will suffice here. (1) e-Criterion (Chomsky 1981, p. 36): Each argument bears one and only one H-role, and each H-role is assigned to one and only one argument. -

PUMICE: a Multi-Modal Agent That Learns Concepts and Conditionals

PUMICE: A Multi-Modal Agent that Learns Concepts and Conditionals from Natural Language and Demonstrations Toby Jia-Jun Li1, Marissa Radensky2, Justin Jia1, Kirielle Singarajah1, Tom M. Mitchell1, Brad A. Myers1 1Carnegie Mellon University, 2Amherst College {tobyli, tom.mitchell, bam}@cs.cmu.edu, {justinj1, ksingara}@andrew.cmu.edu, [email protected] Figure 1. Example structure of how PUMICE learns the concepts and procedures in the command “If it’s hot, order a cup of Iced Cappuccino.” The numbers indicate the order of utterances. The screenshot on the right shows the conversational interface of PUMICE. In this interactive parsing process, the agent learns how to query the current temperature, how to order any kind of drink from Starbucks, and the generalized concept of “hot” as “a temperature (of something) is greater than another temperature”. ABSTRACT CCS Concepts Natural language programming is a promising approach to •Human-centered computing ! Natural language inter enable end users to instruct new tasks for intelligent agents. faces; However, our formative study found that end users would of ten use unclear, ambiguous or vague concepts when naturally Author Keywords instructing tasks in natural language, especially when spec Programming by Demonstration; Natural Language Pro ifying conditionals. Existing systems have limited support gramming; End User Development; Multi-modal Interaction. for letting the user teach agents new concepts or explaining unclear concepts. In this paper, we describe a new multi- INTRODUCTION modal domain-independent approach that combines natural The goal of end user development (EUD) is to empower language programming and programming-by-demonstration users with little or no programming expertise to program [43]. -

Veridicality and Utterance Meaning

2011 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing Veridicality and utterance understanding Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Christopher D. Manning and Christopher Potts Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 {mcdm,manning,cgpotts}@stanford.edu Abstract—Natural language understanding depends heavily on making the requisite inferences. The inherent uncertainty of assessing veridicality – whether the speaker intends to convey that pragmatic inference suggests to us that veridicality judgments events mentioned are actual, non-actual, or uncertain. However, are not always categorical, and thus are better modeled as this property is little used in relation and event extraction systems, and the work that has been done has generally assumed distributions. We therefore treat veridicality as a distribution- that it can be captured by lexical semantic properties. Here, prediction task. We trained a maximum entropy classifier on we show that context and world knowledge play a significant our annotations to assign event veridicality distributions. Our role in shaping veridicality. We extend the FactBank corpus, features include not only lexical items like hedges, modals, which contains semantically driven veridicality annotations, with and negations, but also structural features and approximations pragmatically informed ones. Our annotations are more complex than the lexical assumption predicts but systematic enough to of world knowledge. The resulting model yields insights into be included in computational work on textual understanding. the complex pragmatic factors that shape readers’ veridicality They also indicate that veridicality judgments are not always judgments. categorical, and should therefore be modeled as distributions. We build a classifier to automatically assign event veridicality II. CORPUS ANNOTATION distributions based on our new annotations. -

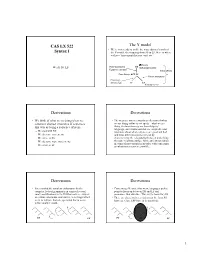

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras To cite this version: Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras. Romani Syntactic Typology. Yaron Matras; Anton Tenser. The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics, Springer, pp.187-227, 2020, 978-3-030-28104- 5. 10.1007/978-3-030-28105-2_7. halshs-02965238 HAL Id: halshs-02965238 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02965238 Submitted on 13 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romani syntactic typology Evangelia Adamou and Yaron Matras 1. State of the art This chapter presents an overview of the principal syntactic-typological features of Romani dialects. It draws on the discussion in Matras (2002, chapter 7) while taking into consideration more recent studies. In particular, we draw on the wealth of morpho- syntactic data that have since become available via the Romani Morpho-Syntax (RMS) database.1 The RMS data are based on responses to the Romani Morpho-Syntax questionnaire recorded from Romani speaking communities across Europe and beyond. We try to take into account a representative sample. We also take into consideration data from free-speech recordings available in the RMS database and the Pangloss Collection. -

Definiteness and Determinacy

Linguistics and Philosophy manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Definiteness and Determinacy Elizabeth Coppock · David Beaver the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract This paper distinguishes between definiteness and determinacy. Defi- niteness is seen as a morphological category which, in English, marks a (weak) uniqueness presupposition, while determinacy consists in denoting an individual. Definite descriptions are argued to be fundamentally predicative, presupposing uniqueness but not existence, and to acquire existential import through general type-shifting operations that apply not only to definites, but also indefinites and possessives. Through these shifts, argumental definite descriptions may become either determinate (and thus denote an individual) or indeterminate (functioning as an existential quantifier). The latter option is observed in examples like `Anna didn't give the only invited talk at the conference', which, on its indeterminate reading, implies that there is nothing in the extension of `only invited talk at the conference'. The paper also offers a resolution of the issue of whether posses- sives are inherently indefinite or definite, suggesting that, like indefinites, they do not mark definiteness lexically, but like definites, they typically yield determinate readings due to a general preference for the shifting operation that produces them. Keywords definiteness · descriptions · possessives · predicates · type-shifting We thank Dag Haug, Reinhard Muskens, Luca Crniˇc,Cleo Condoravdi, Lucas -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Dative Shift) • Interactions Among Lexical Rules 2

Grammar Development with LFG and XLE Miriam Butt University of Konstanz Last Time • LFG and XLE basics • C-structure and f-structure • Functional annotation • Unification/Consistency, Completenes and Coherence • Templates • XLE Walkthrough This Time: Lesson 3 1. Lexical Rules • Passive • English Dative Alternation (Dative Shift) • Interactions among Lexical Rules 2. Different types of functional equations/constraints Lexical rules (vs. Transformations) ! A feature that LFG is very well known for is the Lexical Rule. ! At the time LFG was invented, generalizations between certain types of sentences were thought of in terms of syntactic transformations. ! A famous example involved the passive. ! Linguistic Observation: active clauses are related to passive clauses via a generalizable rule. » Active: The tiger chased the cat. » Passive: The cat was chased by the tiger. Transformations ! For example, within Transformational Grammar the rule for the English passive looked something like this: NP1 V NP2 → NP2 AUX V by NP1 ! In our example: NP1 = the tiger NP2 = the cat V = chased Aux = was ! Over time, however, it was realized that this was not the best way to express what happens with passives across languages. Lexical rules ! Work by David Perlmutter and Paul Postal showed that the relationship between active and passive was best understood in terms of grammatical relations. ! In LFG terms, this was formulated in terms of a Lexical Rule: – OBJ → SUBJ – SUBJ → Adjunct or OBL-AG (OBL agent) ! Verbs which allow for the passive encode this rule as part of their lexical entry. Lexical rules ! Not all verbs allow for passivization. ! Passives are generally formed with agentive (di)transitive verbs. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Tagalog Pala: an Unsurprising Case of Mirativity

Tagalog pala: an unsurprising case of mirativity Scott AnderBois Brown University Similar to many descriptions of miratives cross-linguistically, Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s clas- sic descriptive grammar of Tagalog describes the second position particle pala as “expressing mild surprise at new information, or an unexpected event or situation.” Drawing on recent work on mi- rativity in other languages, however, we show that this characterization needs to be refined in two ways. First, we show that while pala can be used in cases of surprise, pala itself merely encodes the speaker’s sudden revelation with the counterexpectational nature of surprise arising pragmatically or from other aspects of the sentence such as other particles and focus. Second, we present data from imperatives and interrogatives, arguing that this revelation need not concern ‘information’ per se, but rather the illocutionay update the sentence encodes. Finally, we explore the interactions between pala and other elements which express mirativity in some way and/or interact with the mirativity pala expresses. 1. Introduction Like many languages of the Philippines, Tagalog has a prominent set of discourse particles which express a variety of different evidential, attitudinal, illocutionary, and discourse-related meanings. Morphosyntactically, these particles have long been known to be second-position clitics, with a number of authors having explored fine-grained details of their distribution, rela- tive order, and the interaction of this with different types of sentences (e.g. Schachter & Otanes (1972), Billings & Konopasky(2003) Anderson(2005), Billings(2005) Kaufman(2010)). With a few recent exceptions, however, comparatively little has been said about the semantics/prag- matics of these different elements beyond Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s pioneering work (which is quite detailed given their broad scope of their work). -

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing

Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject-Sharing and Index-Sharing Juwon Lee The University of Texas at Austin Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar University at Buffalo Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2014 CSLI Publications pages 135–155 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2014 Lee, Juwon. 2014. Two Types of Serial Verb Constructions in Korean: Subject- Sharing and Index-Sharing. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 21st In- ternational Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, University at Buffalo, 135–155. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract In this paper I present an account for the lexical passive Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) in Korean. Regarding the issue of how the arguments of an SVC are realized, I propose two hypotheses: i) Korean SVCs are broadly classified into two types, subject-sharing SVCs where the subject is structure-shared by the verbs and index- sharing SVCs where only indices of semantic arguments are structure-shared by the verbs, and ii) a semantic argument sharing is a general requirement of SVCs in Korean. I also argue that an argument composition analysis can accommodate such the new data as the lexical passive SVCs in a simple manner compared to other alternative derivational analyses. 1. Introduction* Serial verb construction (SVC) is a structure consisting of more than two component verbs but denotes what is conceptualized as a single event, and it is an important part of the study of complex predicates. A central issue of SVC is how the arguments of the component verbs of an SVC are realized in a sentence.