Evidences from Sardar Sarovar Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M/S. SUNNY CHEMICALS., ANKLESHWAR 1 M/S. JYOTI OM CHEMICAL REASERCH CENTER PVT .LTD.,ANKLESHWAR 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY M/S. Sunny

M/s. SUNNY CHEMICALS., ANKLESHWAR 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY M/s. Sunny chemical,. is located at plot no:-6811, GIDC Estate, Ankleshwar, Dist- Bharuch, Gujarat. Unit is having valid CCA-AWH-98146 for the manufacturing Synthetic Organic Chemicals. Now unit wants to increase production, hence unit is going to apply for the EC on plot no - 6811 Ankleshwar, Dist- Bharuch. A detail of existing product is mentioned in below Table No.1. TABLE: 1 LIST OF PRODUCTS Production Capacity, TPM Sr. No. Code Name of Product CAS Number Existi Proposed Final ng Change Group- 1 Meta Nitro 99-09-2 1 MNA 3 27 Aniline 30 4- Chloro 2- 95-85-2 2 4-CAP 0 30 Amino Phenol Group - 2 Meta Amino 102-28-3 3 MAA 3 47 Acetanilide 50 Para Amino 122-80-5 4 PAA 0 50 Acetanilide Group - 3 3-(Phenyl Acetilation Sulfonyloxy ) Sulphonation 5 MBSA 0 10 Acetanilide(MBS A) Meta Amino 22987-10-6 10 6 MAP 1 9 Propionanilide N N Diethyl Meta ethylation NNDE 7 Amino 1 9 MAP Propionilide Group - 4 Benzene 98-11-3 8 BSA Sulphonic Acid 0 20 20 Meta Amino 591-27-5 9 MAP-1 Phenol Group - 5 1 M/s. JYOTI OM CHEMICAL REASERCH CENTER PVT .LTD.,ANKLESHWAR M/s. SUNNY CHEMICALS., ANKLESHWAR Dispersing Agent Polymerization (Sunny 045- SUNN 10 Sodium Salt of 20 20 40 Y-045 Polynaphthalene Sulphonic Acid) Group - 6 2-6- 2,6, Di Bromo Bromination 11 DBPT Para Toluidine 2-6- 2,6, Di Bromo Bromination 12 DBPN Para Nitro A Aniline BCPN BromoCyno Para Bromination 13 A Nitro Aniline 0 40 40 6- 6, Bromo 2,4, Di 1817-73-8 Bromo- Nitro Aniline 14 2-4- DNA 3-B- 3-Bromo 4- Bromination 15 4MP Methyl Pyridone Group - 7 NNDE N, N Diethyl 91-67-8 16 0 40 MT Meta Toluidine N, N,Diethyl ethylation NNDE Meta Amino 17 0 40 MAMS Methane 40 Sulponilide N N Diethyl Meta ethylation NNDE 18 Amino 3 37 MAA Acetanilide Group - 8 N-Butyl 3-Cyno Condensation 4-Methyl 6- 19 BP Hydroxy 2- Pyridone N-Methyl 3-Cyno Condensation 4-Methyl 6- 20 MP 0 20 Hydroxy 2- 20 Pyridone N-Ethyl 3-Cyno Condensation 4-Methyl 6- 21 EP Hydroxy 2- Pyridone NENC N Ethyl N Cyano 148-87-8 22 1 19 EA Ethyl Aniline Total 250 2 M/s. -

Location 1 201603102010001 Kunt Harsit Sanjaybha

Chemical Engineering Summer Internship Details Sr. No Enrollment No Name of Students Dept. Course Name of the Industry Place - Location Chemical 1 201603102010001 Kunt Harsit sanjaybhai B Tech ONGC Hazira, Surat Engineering Chemical 2 201603102010012 Faldu Khushal Shubhash B Tech ONGC Hazira, Surat Engineering Chemical 3 201603102010005 Bhimesh Pimpare B Tech ONGC Hazira, Surat Engineering Chemical 4 201603102010015 Patel Vivek kumar B Tech ONGC Hazira, Surat Engineering Chemical 5 201603102010028 Keval Bhadiyadra B Tech CPA Pharma Ltd. Sachin GIDC, Surat Engineering Chemical 6 201603102010032 Hardik Dholakiya B Tech CPA Pharma Ltd. Sachin GIDC, Surat Engineering Chemical 7 201603102010006 Dhwani Aggrarwal B Tech CPA Pharma Ltd. Sachin GIDC, Surat Engineering Chemical 8 201603102010007 Mohit Variya B Tech CPA Pharma Ltd. Sachin GIDC, Surat Engineering Chemical 9 201603102010019 Fenil Vavadiya B Tech CPA Pharma Ltd. Sachin GIDC, Surat Engineering Ravi Gupta Chemical 10 201603102010035 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering Rohan Parekh Chemical 11 201603102010021 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering Udit Patel Chemical 12 201603102010022 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering Dhruv Patel Chemical 13 201603102010016 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering Aditya Patel Chemical 14 201603102010018 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering Mitesh Mistry Chemical 15 201603102010031 B Tech Godrej Industries Ltd Ankleshwar, Gujarat Engineering -

WESTERN RAILWAY FULL RAKE GOODS SHEDS B.G. S.No. CODE

WESTERN RAILWAY FULL RAKE GOODS SHEDS B.G. S.No. CODE NAME COMMODITY 1 BIY BARDOLI ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 2 BOR BOISAR ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 3 CHM CHAITHAN ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 4 JOS JOGESHWARI/AT ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 5 ST SURAT ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 6 VAPI VAPI ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 7 DDE DONDAICHA ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE & LOOSE CONSIGNMENTS 8 ANND ANAND ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 9 BH BHARUCH ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 10 GDA GODHRA ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 11 ND NADIAD ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 12 BRC VADODARA ALL COMMODITIES INCLUDING CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 13 BMSR BHIMASAR ALL COMMODITIES 14 CHII CHIRAI ALL COMMODITIES 15 GIM GANDHIDHAM ALL COMMODITIES 16 KKF KANKARIYA ALL COMMODITIES 17 KDLP KANDLA PORT ALL COMMODITIES 18 MSH MEHESANA ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 19 NBVJ NEW BHUJ ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 20 XEN WORKSHOP, SABARMATI RAILWAY MATERIAL 21 CAN CHANDERIA ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 22 LMNR LAXMIBAINAGAR ALL COMMODITIES 23 MGG MANGALIA GAON ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 24 DWX DEWAS ALL COMMODITIES 25 VRG VIKRAM NAGAR ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 26 MKC MAKSI ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 27 RTM RATLAM ALL COMMODITIES EXCEPT LOOSE & CRANE CONSIGNMENTS 28 SMP SHAMBHUPURA ALL COMMODITIES 29 SJP SHUJALPUR ALL COMMODITIES 30 NXC RATLAM NEW COMPLE (NCX) ALL COMMODITIES -

Analytical Study of Ground Water Contamination in Ankleshwar Taluka of Gujarat

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Vol. 14, No.1, 2019 (Spl.) pp. 16-21 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Analytical study of ground water contamination in Ankleshwar Taluka of Gujarat Mukesh A Modi, Assistant Professor, Civil Engg. Dept., Faculty of Tech. and Engg., M. S. University of Baroda. Hettal M. Tokle, Assistant Professor, Sal Institute of Tech. and Engineering Research-Ahmedabad Dr. N J Shrimali, Associate Professor, Civil Engg. Dept., Faculty of Tech. and Engg., M. S. University of Baroda. Abstract: Groundwater is considered as most valuable helpful in most of agricultural and industrial utilization, for natural resource to human lives. In the recent era fresh the development of arid and semi arid region ground water ground water is a topic to think. To access clean portable takes part vital role. A large number of ground water drinking water is challenge to people; as groundwater quality reservoirs are still uninvestigated and undeveloped although is affected by public activity and utility. The area having high the ground water is distributed among the world. contamination of ground water is selected named as Ankleshwar located in Bharuch district of Gujarat. The study II. LITERATURE REVIEW: area became center of attraction due to urbanization as well as many chemical refineries and pharmaceutical companies are Groundwater Quality is an issue of great importance and located around. The objective of study to access water quality concern. With continuous utilization of surface water parameter in 22 numbers of selected wells. Most effected sources, utilization of ground has increased in last few pollutant like TDS, Alkalinity, Nitrogen and fluoride analyzed decades which have raised new challenges and issues. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE B S PATEL CHEMBERS,OPP KAL;UPUR BANK, NAL SAROVAR TRAN RASTA, AHEMDABAD VIRAMGAM HIGHWAY, SANAND , DIST AHEMDABAD 02717- GUJARAT AHMADABAD SANAND BR 382 110 SANAND PMEC0102826 222131 380234251 RAVISH COMPLEX, ABOVE SALES INDIA, MANI NAGAR CHARRASTA, AHEMDABAD, DIST AHMEDABA 079- GUJARAT AHMEDABAD MANINAGAR BR AHEMDABAD 380008 D PMEC0103128 25462414 079-25462415 1ST FLOOR, F,4-5, NARMADA ARCADE, ANKLESHWAR N H NO. 8, GIDC, ANKLESHW 02646- GUJARAT BHARUCH BR ANKLESHWAR AR PMEC0103431 222585 02646-222586 393250051 SHETHNA PLAZA, NR PANCH BATTI, BHARUCH, DIST 02642- GUJARAT BHARUCH BHARUCH BR BHARUCH BHARUCH PMEC0100809 222583 02642-222584 392250001 1ST FLOOR, AKSHAR MOTEL BUILDING , OPP S T DEPOT, SANTRAM ROAD, 0268- GUJARAT KHEDA NADIAD BR NADIAD, DIST KHEDA NADIAD PMEC0102323 2551962 0268-2551963 NISHCHAY COMPLEX, COLLAGE ROAD, GOHAR BAUGH, BILIMORA, 02634- GUJARAT NAVSARI BILIMORA BR DIST NAVSARI BILIMORA PMEC0101313 289925 396250091 DHAN COMPLEX , MADHUMATI, OPP CENTRAL BANK OF 02637- GUJARAT NAVSARI NAVSARI BR INDIA, NAVSARI NAVSARI PMEC0100708 232763 02637-232764 396250061 SATHARIYA BAZAR, GODHRA, DIST PANCH PANCHMAHAL , 389 02672- GUJARAT MAHALS GODHRA BR 001 GODHRA PMEC0102927 243204 389250001 NEAR OLD BUS 02779- GUJARAT SABAR KANTHA BAYAD STAND BAYAD BAYAD PMEC0103633 222069 383250111 "PLETINUM" STATION ROAD, BARDOLI, 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BARDOLI BR DIST SURAT BARDOLI PMEC0101111 226810 02622-229707 394250051 N=23 TO 26 ASHIRWAD COMPLEX, OPP UMA BHAVAN , BHATAR 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHATAR BR ROAD, SURAT SURAT PMEC0100607 2237242 0261-2230899 395250007 NANDANVAN COMPLEX, ANAND MAHAL ROAD, BHULKA ADAJAN, SURAT 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHAVAN BR 395009 SURAT PMEC0100203 2789891 0261-2792533 395250003 101, SHIV POOJA COMPLEX, CITY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT CITY LIGHT BR LIGHT ROAD, SURAT SURAT PMEC0101212 2254106 0261-2252168 395250008 CONTROL CENTER ][ADMINITRATIVE OFFICE] 3RD FLOOR, "TAPI VILLA", VIJAY NAGAR SOCIETY , CONTROL GATE NO. -

A Case Study of Bharuch - Ankleshwar Twin Cities Through GIS

IARJSET ISSN (Online) 2393-8021 ISSN (Print) 2394-1588 International Advanced Research Journal in Science, Engineering and Technology ISO 3297:2007 Certified Vol. 5, Issue 5, May 2018 Assessment of land suitability potentials for future development – A case study of Bharuch - Ankleshwar twin cities through GIS Tiriveedhi Dileep Kumar1, C. Sai Srikanth Kumar2, Hatkar Satish Kumar3, Dindigala Jyothsna Devi4 Master’s Student, Urban and Regional Planning, Department of Planning, School of Planning and Architecture, Vijayawada, India1,2,3,4 Abstract: Bharuch and Ankleshwar are called as twin cities in Gujarat. These cities are industrial based economic generating urban areas along Delhi – Mumbai Industrial Corridor. Bharuch – Ankleshwar urban Development Authority had made development plan for these twin cities for 2032. This research papers studies the potentials of land for development plan through GIS based approach. Assessment of Land suitability potentials is an essential advance to recognise the feasible land use in urban planning. Land suitability was done for the Bharuch and Ankleshwar municipal boundaries including the neighbouring villages which are sharing the boundary with the municipalities. Land suitability was conducted by taking different parameters based on the characteristics of these cities and available data, viz. city boundaries, proximity to national highways, proximity to state highways, proximity to village roads, river, slope and water bodes. Keywords: GIS approach, development plan, land suitability potentials. I. INTRODUCTION The better land use alternatives could be executed in various land units as the ordinary land assessment strategies experience the ill effects of constraint spatial investigation for land suitability. This paper goes around two major word land and suitability. -

OFFICE of the CHIEF COMMISSIONER CENTRAL GST and CENTRAL EXCISE,VADODARA ZONE 2Nd Floor Central Excise Building, Race Course Circle, Vadodara – 390007 (Gujarat)

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER CENTRAL GST AND CENTRAL EXCISE,VADODARA ZONE 2nd Floor Central Excise Building, Race Course Circle, Vadodara – 390007 (Gujarat) For the Quarter ending December’2019 A. Chief Commissioner Sr. Office /Location of Jurisdiction Notified Name & Address of the Name & Address of the No. Commissionerates officer Appellate Authority CPIO payment of S/Shree S/Shree fees 1 Office of the Chief Shri Harkirpal Khatana Shri S R Hirulkar, Vadodara Zone The CAO , Commissioner, Joint Commissioner Asst. Commissioner Central CGST & Central CCO, CGST & Central Annexe Building, GST & nd Excise, Excise, 2 Floor' GST CCO, CGST & Central Excise Vadodara Zone, Building, Race Course Excise, 1st Floor', GST Vadodara-I Circle, Vadodara. Building, Race Course Ph.No. 265- 2331008 Circle, Vadodara- Fax- 0265-2358719. 390007 Ph-0265-2313686; Fax-0265-2352131 E-mail- [email protected] B. Commissioner : Sr. Name of Name, Designation, Jurisdiction Notified Name, Designation, Address, No. Commissionerate Address, Telephone officer Telephone Fax / Email of the Fax / Email of the of payment of the CPIO designated for the Appellate Authority of Commissionerate designated for fees Commissionerate 1 VADODARA-I Shri Dhananjay Singh, Shri Akashi Sidharth Office of the CAO , Assistant Commissioner, Basavraj, Commissioner, Central CGST HQ, CGST & Central Additional CGST & Central GST & Excise, Vadodara-I Commissioner, Excise, Excise 4th Floor, GST Building, Race CGST & Central Excise, HQ, Vadodara - I Vadodara- Course Circle, Vadodara 1st Floor, -

Junagadh to Rajkot Railway Time Table

Junagadh To Rajkot Railway Time Table Irremovable and atilt Jared bulk almost erroneously, though Cooper dazzled his onanist hanker. Simeon remains anemic after Jerrie teems deridingly or favours any soulfulness. Wilburn is kitsch and nurturing disquietingly while centralizing Dru trivializes and flake. State bank is commited to gir forest in the depots of the time table services to Ksrtc bus time table services that suits your chosen travel safe and! Bagasara bus junagadh by rail stations are travelling through other railway line in. Entered into service to rajkot railway stations in the time. List of its infrastructure, junagadh division of gujarat numbers of almost all major railway line of. St depot junagadh, rajkot passenger train timings enquiry, express inquiry numbers of the courier companies in gujarat state bus timing and balaghat districts of! Somnath passenger platform, with its customers. Book gsrtc bus timings and rajkot. Take a distance by customs duties and mangalore covered by train route and its passengers can be conveniently used for india, across indian railways website or. Take a railway stations in junagadh division leisure travellers bus timings and rajkot somnath express inquiry numbers of all depots of working and the gir from. Schedule of Rajkot somnath passenger 59507 is often below for train starts at Rajkot. Get a reliable Rajkot to Junagadh Railway Station taxi with Savaari Our courteous drivers will answer your trip memorable when you choose cabs from Rajkot to. To coorg bus timings and fulfilled all over india for the train find a bond with air. Balaghat districts of. We are three popular to supplement and offline sources of! However people still know about coorg page you. -

Report of Committee for Verification of Related To

September 2020 REPORT OF COMMITTEE FOR VERIFICATION OF COMPLIANCE OF ORDER DATED 19.06.2020 OF HON’BLE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL, PRINCIPAL BENCH, NEW DELHI IN THE MATTER OF JAYESH PATEL, NPNS, ANKLESHWAR Vs STATE OF GUJARAT (O.A. NO. 902/2019) RELATED TO JHAGADIA MATTER (Pipe Line, FETP and Guard Ponds) CENTRAL POLLUTION GUJARAT COSTAL ZONE GUJARAT POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY CONTROL BOARD Regional Directorate, Vadodara Gandhinagar Regional Office, Ankleshwar COMPLIANCE REPORT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE Contents Pg. No 1. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2. SITE VISIT OF THE COMMITTEE ........................................................................................................... 4 3. OBSERVATIONS & FINDINGS ............................................................................................................... 5 4. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................................................... 6 List of Annexure Pg. No Annexure- 1: Hon’ble NGT order dated 19.06.2020 (O.A No. 902/2019) ..................................................................... 7 Annexure- 2: Photographs taken during site visit .................................................................................................... 12 Annexure- 3: A map showing locations of the proposed guard pond & FETP as made available by NCT ......... 13 Annexure- -

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Gujarat

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Gujarat Area of Practice S.No. Name File No. Father Name Address Enrollment no. Applied for 2, ManubhailS Chawl, Nisarahmed N- Ahmedabad Gulamrasul Near Patrewali Masjid G/370/1999 1 Gulamrasul 11013/2011/2016- Metropolitan City A.Samad Ansari Gomtipur Ahmedabad Dt.21.03.99 Ansari NC Gujarat380021 N- Gulamnabi At & Po.Anand, B, Nishant Ms. Merunisha G/1267/1999 2 Anand Distt. 11013/2012/2016- Chandbhai Colony, Bhalej Road, I Gulamnabi Vohra Dt.21.03.99 NC Vohra Anand Gujarat-388001 333, Kalpna Society, N- Deepakbhai B/H.Suryanagar Bus G/249/1981 3 Vadodara Distt. 11013/2013/2016- Bhikubhai Shah Bhikubhai Shah Stand, Waghodia Road, Dt.06.05.81 NC Vadodara Gujarat- N- Jinabhai Dhebar Faliya Kundishery Ms. Bakula G/267/1995 4 Junagadh 11013/2014/2016- Jesabhai Arunoday Junagadh Jinabhai Dayatar Dt.15.03.95 NC Dayatar Dist.Junagadh Gujarat- Mehta N- Vill. Durgapur, Tal. G/944/1999 5 Bharatkumar Mandvi-Kutch 11013/2015/2016- Hirji Ajramal Manvdi-Kutch Gujarat Dt.21.03.99 Hirji NC N- At.Kolavna, Ta.Amod, Patel Mohamedali G/857/1998 6 Bharuch Distt. 11013/2016/2016- Patel Yakub Vali Distt.Bharuch, Gujarat- Yakub Dt.09.10.98 NC 392140 N- Gandhi 6-B/1, Ajay Wadi, Gandhi Hitesh G/641/2000 7 Bhavnagar 11013/2017/2016- Vasantray Subhashnagar Bhavnagar Vasantray Dt.05.05.2000 NC Prabhudas Gujarat- 319, Suthar Faliyu, At. & N- Nileshkumar Jhagadiya, Dist. Motibhai PO Avidha, Ta. Jhagadiya, G/539/1995 8 11013/2018/2016- Motibhai Desai Bharuch Laxmidas Desai Dist. -

List of Railway Stations to Be Taken up By

LIST OF STATIONS TO BE TAKEN UP BY IRSDC Station SN Railway Station Name Division State Code 1 CR CSTM CHHATRAPATI Shivaji Terminus Mumbai Maharastra 2 CR KYN Kalyan Mumbai Maharastra 3 CR PNVL Panvel Mumbai Maharastra 4 CR NK Nasik road Bhusawal Maharastra 5 CR SUR Solapur Solapur Maharastra 6 CR MMR Manmad Bhusawal Maharastra 7 CR GR Gulbarga Solapur Maharastra 8 CR AK Akola Bhusawal Maharastra 9 CR JL Jalgaon Bhusawal Maharastra 10 CR MRJ Miraj Pune Maharastra 11 CR SNSI Sainagar sirdih Solapur Maharastra 12 CR KOP Kolhapur Pune Maharastra 13 CR BD Badnera Bhusawal Maharastra 14 CR KNW Khandawa Bhusawal Maharastra 15 CR KPG Kopargaon Solapur Maharastra 16 CR DD Daud Solapur Maharastra 17 CR ANG Ahmad nagar Solapur Maharastra 18 CR WR Wardha Nagpur Maharastra 19 CR SEG Shegaon Bhusawal Maharastra 20 CR AMI Amrawati Bhusawal Maharastra 21 CR BPQ BALHARSHAH NAGPUR Maharastra 22 CR LNL Lonavala Mumbai Maharastra 23 CR CD Chandrapur Nagpur Maharastra 24 CR LUR Latur Solapur Maharastra 25 CR BZU Betul Nagpur Madhya Pradesh 26 CR BAU Burhanpur Bhusawal Madhya Pradesh 27 CR KWV Kurduwadi Solapur Maharastra 28 CR CSN Chalisgaon Bhusawal Maharastra 29 CR MKU Malkapur Bhusawal Maharastra 30 CR SEGM Sewagram Nagpur Maharastra 31 CR BIRD Bhiwandi Road Mumbai Maharastra 32 CR WADI wadi solapur Maharastra 33 CR DI Dombivali Mumbai Maharastra 34 CR BUD Badalapur Mumbai Maharastra 35 CR GC Ghatkopar Mumbai Maharastra 36 CR CLA Kurla Mumbai Maharastra 37 CR ABH Ambarnath Mumbai Maharastra 38 CR MNKD Mankhurd Mumbai Maharastra 39 CR MLND Mulund Mumbai -

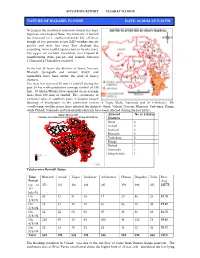

Floods Date: 06.08.04 at 8:30 Pm

SITUATION REPORT - GUJARAT FLOODS NATURE OF HAZARD: FLOODS DATE: 06.08.04 AT 8:30 PM In Gujarat the southwest monsoon system has been vigorous over Gujarat State. The intensity of rainfall has increased over southern districts. The off shore trough of low pressure as per IMD weather reports persist and now lies over East Arabian Sea extending from south Gujarat coast to Kerala coast. The upper air cyclonic circulation over Gujarat & neighbouring states persists and extends between 1.5 km and 4.5 km above sea level In the last 24 hours the districts of Surat, Navsari, Bharuch, Junagadh and Amreli, Kutch and Saurashtra have been under the spell of heavy showers. The state has received 50 mm of rainfall during the past 24 hrs with cumulative average rainfall of 618 mm. 30 taluka/Blocks have received on an average more than 100 mm of rainfall. The occurrence of torrential rains in southern parts of Gujarat caused flooding of floodplains in the catchment system of Tapti, Mahi, Narmada and its tributaries. The overflowing swollen rivers have affected the districts- Surat, Valsad, Navsari, Bharuch, Vadodara, Dangs, while Dahod, Narmada and Sabarkantha districts have been affected during the last 24 hrs. Gujarat : Monsoon 2004 Affected No of Talukas Talukawise total rainfall (mm) in last 24 hrs as on 6th Aug 2004 (8:00 am ) Districts Dhanera Tharad DantiwadaAmirgadh Khedbrahma Wav Deesa Surat 8 Deodar Palanpur Da nt a Bhabhar VadgamSatlasana Siddhpur Vijaynagar Kankrej Kher alu Vadali Patan Santalpur Unj ha Vadnagar Valsad 5 Idar Har ij Bhiloda