Alexander R. Galloway and Eugene Thacker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horror of Philosophy

978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page i In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page ii 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iii In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] Eugene Thacker Winchester, UK Washington, USA 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iv First published by Zero Books, 2011 Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website. Text copyright: Eugene Thacker 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84694 676 9 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers. The rights of Eugene Thacker as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design: Stuart Davies Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. -

REVIEW ARTICLE James W. Heisig, Philosophers of Nothingness: an Essay on the Kyoto School University of Hawaii Press, 2001

PARRHESIA NUMBER 10 • 2010 • 87-92 REVIEW ARTICLE James W. Heisig, Philosophers of Nothingness: An Essay on the Kyoto School University of Hawaii Press, 2001 Eugene Thacker 1. DEATH IN DEEP SPACE There is a motif commonly found in science fiction, which derives from earlier narratives of nautical adven- ture and stories of castaways. The motif is that of the sole human being, unmoored, set loose, and adrift in space. One of the most popular versions of this is found in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which astronaut Frank Poole is set loose by the intelligent supercomputer HAL to drift aimlessly into the depths of deep space. In the film Kubrick portrays the scene without a soundtrack or, for that matter, any sound at all. The scene of being set adrift into space is depicted with silent horror: all we as viewers see is a lone figure speeding off into a black abyss. JAMES W. HEISIG, PHILOSOPHERS OF NOTHINGNESS During the Golden Age of science fiction in the 1920s and 1930s, pulp authors tended to depict the “adrift in space” motif as being “lost in space,” that is, as a by-product of inter-galactic adventure narratives. One was only lost in space until the next adventure, the next battle, the next conquest. However, for earlier works—most notably Camille Flammarion’s metaphysical science fiction Lumen—being adrift in space is less a by-way to yet another adventure, but a speculative opportunity in and of itself. Being adrift in space is the story itself, so much so that Edgar Allen Poe could pen entire cosmic dialogues around the theme, without character, plot, or setting. -

Nine Disputations on Theology and Horror Eugene Thacker

COLLAPSE IV Nine Disputations on Theology and Horror Eugene Thacker 1. AFT E R -LIF E Ever since Aristotle distinguished the living from the non-living in terms of psukhê – commonly translated as ‘soul’ or ‘life-principle’ – the concept of ‘life’ has itself been defined by a duplicity – at once self-evident and yet opaque, capable of categorization and capable of further mystifica- tion. This duplicity is related to a another one, namely, that there are also two Aristotles – Aristotle-the-metaphysician, rationalizing psukhê, form, and causality, and Aristotle-the- biologist, observing natural processes of ‘generation and corruption’ and ordering the ‘parts of animals’. Arguably, the question of life is the burning question of the contemporary era, one in which life is everywhere at stake as ‘bare life’, one in which ‘all politics is biopolitics’. If the question of Being was the central issue for antiquity (raised again by Heidegger), and if the question of God 55 COLLAPSE IV – as alive or dead – was the central issue for modernity (Kierkegaard, Nietzsche), then perhaps the central question today is that of Life – the function of the concept of ‘life itself’, the two-fold approach to life as at once scientific and mystical, the return of vitalisms of all types, and the pervasive politicization of life. The question that runs through these brief disputatio is the following: Can there be an ontology of ‘life’ that does not immediately become a concern of either Being or God? Put differently, if one accepts that the concept of ‘life’ is -

Renaissance and Early Modern Philosophy

Late Modern Philosophy (PHH 4440) W-F, 12:00-1:50 p.m. ED/112 Instructor: Dr. Marina P. Banchetti Office: SO/280 Contact Information: 297-3816 or [email protected] Office Hours: W-F, 10:00-11:00 a.m. 3:30-4:30 p.m. Credit Hours: 4 credits Klaus Kinski as Fitzcarraldo (Dir. Werner Herzog) Textbooks: W. T. Jones, A History of Western Philosophy, Volume IV: Kant and the Nineteenth Century, second edition, revised (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1997). Immanuel Kant, Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics, the Paul Carus translation, extensively revised by James W. Ellington (New York: Hackett Publishing Company, 1977). Immanuel Kant, Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, translated and with an introduction by Lewis White Beck (Indianapolis: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 1990). G.W.F. Hegel, Reason in History, translated and with an introduction by Robert S. Hartman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967). G.W.F. Hegel, Philosophy of Right, translated with notes by T. M. Knox (Indianapolis: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 1998). 2 Arthur Schopenhauer, Philosophical Writings, edited by Wolfgang Schirmacher, translated by E. F. Payne (New York: Continuum Press, 1998). Additional required and recommended readings are posted on Blackboard. Course Credit Hours: This 4-credit course fulfills a core history of philosophy requirement for the philosophy major. The prerequisite for this course is PHH 3420 (“Early Modern Philosophy”). Catalog Description: An in-depth study of major 18th and 19th century European philosophers, with an emphasis on Kant and Hegel, though other philosophers may also be covered. The course focuses on contributions to metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and social and political philosophy. -

Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY By tommy symmes A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE William B Parsons William B Parsons (Apr 21, 2021 11:48 PDT) William Parsons Jeffrey Kripal Jeffrey Kripal (Apr 21, 2021 13:45 CDT) Jeffrey Kripal James Faubion James Faubion (Apr 21, 2021 14:17 CDT) James Faubion HOUSTON, TEXAS April 2021 1 Abstract This dissertation studies dance music events in a field survey of writings, in field work with interviews, and in conversations between material of interest sourced from the writing and interviews. Conversations are arranged around six reading themes: events, ineffability, dancing, the materiality of sound, critique, and darkness. The field survey searches for these themes in histories, sociotheoretical studies, memoirs, musical nonfiction, and zines. The field work searches for these themes at six dance music event series in the Twin Cities: Warehouse 1, Freak Of The Week, House Proud, Techno Tuesday, Communion, and the Headspace Collective. The dissertation learns that conversations that take place at dance music events often reflect and engage with multiple of the same themes as conversations that take place in writings about dance music events. So this dissertation suggests that writings about dance music events would always do well to listen closely to what people at dance music events are already chatting about, because conversations about dance music events are also, often enough, conversations about things besides dance music events as well. 2 Acknowledgments Thanks to my dissertation committee for reading this dissertation and patiently indulging me in conversations about dance music events. -

In the Dust of This Planet: Eugene Thacker Confronts the Unthinkabl

In the Dust of This Planet: Eugene Thacker Confronts the Unthinkabl... http://blogs.newschool.edu/news/2014/11/eugene-thacker-confronts-... THE NEW SCHOOL (HTTP://NEWSCHOOL.EDU/ NEWS (/NEWS/) (http://blogs.newschool.edu/news/2014 /11/eugene-thacker-confronts-the-unthinkable/) Eugene Thacker, author, philosopher and associate professor of Media Studies and Film at New School for Public Engagement and Liberal Studies at The New School for Social Research, has written several books focusing on nihilism, philosophy and media theory. II nn tt hhee DDuusstt ooff You know you’ve made it when Glenn Beck views you as a threat. 1 of 5 8/12/15 8:56 PM In the Dust of This Planet: Eugene Thacker Confronts the Unthinkabl... http://blogs.newschool.edu/news/2014/11/eugene-thacker-confronts-... That’s the position Eugene Thacker found himself in when, during a TT hh ii ss PP ll aa nn ee tt :: recent episode of The Glenn Beck Program (http://www.youtube.com /watch?v=2IW8OK4_1gQ), the right-wing pundit bashed an “obscure Eugene Thacker author” whose book was contributing to a surge in “pop nihilism.” Referring to a Radiolab episode (http://www.radiolab.org/story/dust- Confronts the planet/) in which Thacker was interviewed, Beck complained that ideas from the author’s book had shown up in the script of the HBO TV Unthinkable series True Detective (http://www.youtube.com /watch?v=A8x73UW8Hjk), the videos of Jay Z and Beyoncé (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNcJg5svv9A), the pages of fashion Nov 4, 2014 magazines (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-2546967/Lily- Collins-rocks-Gothic-look-pale-skin-deep-red-lips-photo-shoot- contrastingly-cheery-Mexican-cantina.html), and the work of Employee Featured (http://blogs.newschool.edu contemporary artists (http://www.maureenpaley.com/artists/gardar- /news/category/hub-features/employee- eide-einarsson/images/14). -

Deleuze, Dark Philosophies, and Global Pandemics by CHRISTIAN FRIGERIO

LA DELEUZIANA – ONLINE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY – ISSN 2421-3098 N. 12 / 2020 – OF EXCESS: OUTLINE OF A PRACTICAL PHILOSOPHY The Virtual and the Viral: Deleuze, Dark Philosophies, and Global Pandemics by CHRISTIAN FRIGERIO Abstract At the point of convergence Between speculative realism, nihilism, and a certain taste for hor- ror culture, “dark philosophies” have emerged as some of the most original theoretical proposals of our times. All these philosophies see virality as the paradigmatic event that disturBs the gloBal axiomatics of capitalism. Today, this gloBality is precisely what gives virality its enormous strength. What dark philosophies can teach us, through a crossed reflection on current social- political conditions and on the concept of life, is how to draw from virality a possiBility for thought: virality is a pharmacological concept, and its meaning will Be in a great part dependent on what we will Be aBle to make of it. A thorough reflection on virality could Bring us to see in the present situation not only a possiBility for new kinds of individuation, But also a catalyst for a type of politics that is perhaps the only possiBility to cope with imperial axiomatics. Introduction: lessons of darkness Darkness is not the aBsence of light…But aB- sorption into the outside. Georges Bataille (1988: 17) The distinction between axiomatics (or theorematics) and proBlematics is among the guiding dichotomies of Deleuze’s philosophy. This opposition has its source in mathe- matics, where it indicates two different modes of formalization and deduction: “in axio- matics, a deduction moves from axioms to the theorems that are derived from it, where- as in proBlematics a deduction moves from the proBlem to the ideal accidents and events that condition the proBlem and form the cases that resolve it” (Smith 2006: 145). -

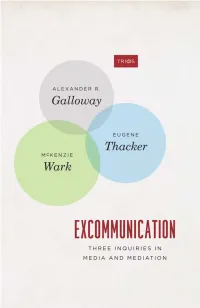

Excommunication: Three Inquiries in Media and Mediation (TRIOS)

EXCOMMUNICATION ALSO PUBLISHED IN THE SERIES Occupy: ree Inquiries in Disobedience Each TRIOS book w. j. t. mitchell, bernard e. addresses an important harcourt, and michael taussig theme in critical theory, e Neighbor: ree Inquiries in Political eology philosophy, or cultural slavoj žižek, eric l. santner, and studies through three kenneth reinhard extended essays wri en in close collaboration by leading scholars. Excommunication THREE INQUIRIES IN MEDIA AND MEDIATION ALEXANDER R. Galloway EUGENE Thacker MCKENZIE Wark e University of Chicago Press Chicago and London ALEXANDER R. GALLOWAY is associate professor of media studies at New York University. He is the author of four books on digital media and critical theory, most recently, e Interface Eff ect. EUGENE THACKER is associate professor in the School of Media Studies at the New School. He is the author of many books, including A er Life, also published by the Univer- sity of Chicago Press. MCKENZIE WARK is professor of liberal studies at the New School for Social Research. His books include A Hacker Manifesto and Gamer eory. e University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 e University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2014 by e University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978-0-226-92521-9 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978-0-226-92522-6 (paper) isbn- 13: 978-0-226-92523-3 (e- book) doi: 10.7208/ chicago/ 9780226925233.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Excommunication : three inquiries in media and mediation / Alexander R. -

On Ascensionism

____________________________________ On Ascensionism Eugene Thacker The New School, New York ____________________________________ The concept of “life” has a privileged but ambivalent position within philosophy. On the one hand, “life” is the topic of regional philosophies whether it be the philosophy of biology, where life is understood in terms of the life sciences, or whether it be in ethical philosophy, where life is understood in terms of the qualified life of the human being. But “life” is not just something that philosophy meditates on as an object of study, for philosophy itself is living thought, a dynamic way of thinking and being in the world. There is not only a thought of life but a life of thought as well. From Aristotle to Descartes to Kant, one can witness this twofold aspect of life in relation to philosophy. Life is that which philosophy thinks about, as a subject an object, and life is also that which conditions the very possibility of philosophy. It is with Kant that one discovers the central dilemma regarding the philosophy of life: if one can posit an order that is specific to the living, does this also presume a purpose that is likewise specific to the living? But the dilemma turns in on itself, for any thought of life must, of course, be thought and is thus not identical with life itself. As Kant notes, any assertion of a concept of life is inseparable from its relative value as a life-for-us as human beings: “If, however, the human being, through the freedom of his causality, finds things in nature completely advantageous for his often foolish aims…one cannot assume here even a relative end of nature” (Kant: §63, 240). -

The Philosophical Side of Contemporary Art Forms

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 The Philosophical Side of Contemporary Art Forms Kristina Bodetti Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PHILOSOPHICAL SIDE OF CONTEMPORARY ART FORMS by KRISTINA BODETTI A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2015 ii ©2015 KRISTINA BODETTI All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. 01-05-2015__________ ___Noel Carroll______________ Date Thesis Advisor 01-12-2015__________ ___Matthew Gold____________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract The Philosophical Side of Contemporary Art Forms By Kristina Bodetti Advisor: Noel Carroll The purpose of this project is to show that contemporary art forms, specifically popular music, film and comics/graphic novels, are capable of, and do in many cases work as philosophical pieces. I believe that an analysis of these mediums will reveal instances in which the works of art explicate established philosophical theories, expand upon them, and in some cases invent new theories. -

Black Metal, Ecology and Contemporary Nihilism

Black Metal, Ecology and Contemporary Nihilism Contents Introduction Chapter 1 - Melanchology and The Blackening of the Green: Black Metal and its Relationship to Ecology 1. What is Melanchology? 2. Black Metal and the Toxic Landscape - The Realists Prophecy 3. Melancholia Forever Chapter 2 – The Black Nihilist 1. Neo-Nietzschean politics in Black Metal and the Creative Force of Nihilism 2. The (active) Black Nihilist Chapter 3 - Contemporary nihilism, are Doomer’s the New Harbingers of Black Bile? 1. Doomers Chapter 4 - Death: Political vs Non-human 1.The Horror of Science and Our Immanent Death Chapter 5 - Annihilation, Chaos Magick (as the Contemporary Emancipatory Mysticism) and Eroti- cizing Nature: George Bataille and Black Metal 6. Conclusion Bibliography After Pandora – Chapter 1 Introduction A feeling of pensive sadness - typically without a cause - eats away, slowly and silently, the endur- ing spirit of man. No human is exempt. This affliction can sink its teeth into any learned soul, it could strike at any time. I refer here to the phenomena of melancholia but specifically a theory of melancholy (aka, melan- chology) as discussed by Scott Wilson in Melanchology, Black Metal theory and Ecology. Pub- lished in 2014, this book is a compilation of texts that discuss the use of a melancholy ideology and aesthetics, combined with ecological concerns and implications, within the black metal musical genre. Black Metal and its insights into an alternate, and somewhat doomed, outlook on ecology and hu- man existence will provide the starting point to this essay. This text, being written by a somewhat nihilistic, culturally privileged, queer Doomer fe/male, will undergo a slime morphology. -

By Alexander R. Galloway, Eugene Thacker and Mckenzie

CULTURE MACHINE CM REVIEWS • 2015 ALEXANDER R. GALLOWAY, EUGENE THACKER, MCKENZIE WARK (2014) EXCOMMUNICATION: THREE INQUIRIES IN MEDIA AND MEDIATION. CHICAGO: UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS. ISBN: 978-0-226-92522-6. Marco Deseriis Excommunication is a strange book, if anything because its agile and crystalline prose often runs into the very limit of what philosophy can and should be able to communicate. The third in the University of Chicago Press Trios series, Excommunication is a three-pronged probe into the aporia of excommunication—the perfomative anti- message that terminating all communications ‘evokes the impossibility of communication’ (16). Make no mistake, Galloway, Thacker, and Wark are not interested in revisiting the deconstructive axiom for which the conditions of possibility of a system ultimately coincide with its conditions of impossibility. Nor do they seem concerned with resuming a version of the Lacanian Real—the foreign, inaccessible, and traumatic dimension that traces the boundaries of the symbolic order. Rather, the essays that make up the book examine philosophical problems that are both much older and much newer than the linguistic turn. They are older in that, as the authors note in the introduction, the question of the conditions of possibility of communication already surfaces in the Phaedrus as the disciple’s threat to Socrates of withdrawing from the discussion becomes instrumental to the continuation of philosophy. And they are much newer as the three New York-based media theorists shun a Socratic and anthropocentric legacy of thinking about communication as presence, interpretation, and discourse in favor of recent philosophical developments such as posthumanism and object- oriented ontology.