Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technics, Precarity and Exodus in Rave Culture

29 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 2 Technics, Precarity and Exodus in Rave Culture TOBIAS C. VAN VEEN MCGILL UNIVERSITY Abstract Without a doubt, the question of rave culture’s politics – or lack thereof – has polarized debate concerning the cultural, social and political value of rave culture not only within electronic dance music culture (EDMC) studies, but in disciplines that look to various manifestations of subculture and counterculture for political innovation. It is time for the groundwork of this debate to be rethought. Ask not what rave culture’s politics can do for you; nor even what you can do for it. Rather, ask what the unexamined account of politics has ever done for anyone; then question all that rave culture has interrogated – from its embodied and technological practices to its production of ecstatic and collective subjectivities – and begin to trace how it has complicated the very question of the political, the communal and the ethical. This complication begins with the dissolution of the boundaries of labour and leisure and the always-already co-optation of culture. To the negation of ethics, community and politics, this tracing calls for the hauntology of technics, precarity and exodus. And it ends with a list of impossible demands demonstrating the parallax gap of rave culture’s politics. Keywords exodus, precarity, technics, multitude, workplay He [Randy] predicted the [rave] parties will eventually disappear under the combined pressure of police, city and fire officials. “In the next year and a half it’s going to vanish”, he said. “Then, when they think it’s gone, it will come back, becoming more underground again”. -

Horror of Philosophy

978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page i In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page ii 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iii In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] Eugene Thacker Winchester, UK Washington, USA 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iv First published by Zero Books, 2011 Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website. Text copyright: Eugene Thacker 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84694 676 9 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers. The rights of Eugene Thacker as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design: Stuart Davies Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. -

26 in the Mid-1980'S, Noise Music Seemed to Be Everywhere Crossing

In the mid-1980’s, Noise music seemed to be everywhere crossing oceans and circulating in continents from Europe to North America to Asia (especially Japan) and Australia. Musicians of diverse background were generating their own variants of Noise performance. Groups such as Einstürzende Neubauten, SPK, and Throbbing Gristle drew larger and larger audiences to their live shows in old factories, and Psychic TV’s industrial messages were shared by fifteen thousand or so youths who joined their global ‘television network.’ Some twenty years later, the bombed-out factories of Providence, Rhode Island, the shift of New York’s ‘downtown scene’ to Brooklyn, appalling inequalities of the Detroit area, and growing social cleavages in Osaka and Tokyo, brought Noise back to the center of attention. Just the past week – it is early May, 2007 – the author of this essay saw four Noise shows in quick succession – the Locust on a Monday, Pittsburgh’s Macronympha and Fuck Telecorps (a re-formed version of Edgar Buchholtz’s Telecorps of 1992-93) on a Wednesday night; one day later, Providence pallbearers of Noise punk White Mice and Lightning Bolt who shared the same ticket, and then White Mice again. The idea that there is a coherent genre of music called ‘Noise’ was fashioned in the early 1990’s. My sense is that it became standard parlance because it is a vague enough category to encompass the often very different sonic strategies followed by a large body of musicians across the globe. I would argue that certain ways of compos- ing, performing, recording, disseminating, and consuming sound can be considered to be forms of Noise music. -

SFMUSIC DAY LIVE + FREE 35 Groups

jazz creative music new music chamber music t early music h e s t 12noon-8pm r i sunday n september 25 G Q 2016 u a r t e t — t h e F Playbill i r s t 2 5 0 y e a r s SFMUSIC DAY LIVE + FREE 35 groups . 155 artists . 4 stages herbst theater . green room atrium theater . education studio san francisco war memorial veterans building 401 van ness avenue . san francisco www. sffcm. org © 2016 dpdp SFMUSIC DAY Sunday September 25, 2016 12:45 Montclair Women’s Big Band ** page 43 1:30 Kasey Knudsen Sextet** page 39 intermission 2:45 Friction Quartet page 36 3:30 Redwood Tango Ensemble** page 47 4:15 Dialogue - Ben Goldberg & Myra Melford** page 32 intermission 5:30 Del Sol String Quartet page 21 6:15 Quartet San Francisco page 22 7:00 Kronos Quartet page 23 HERBST THEATER HERBST 12:00 Sunset Duo** page 51 12:45 martha & monica page 41 1:30 Delphi Trio page 31 intermission 2:45 SF Conservatory of Music Faculty Artists Quartet page 17 3:15 Telegraph Quartet page 18 3:55 Chamber Music Society of San Francisco page 19 4:30 Thalea Quartet page 20 intermission 5:30 New Esterházy Quartet page 46 THE GREEN ROOM 6:15 Earplay page 33 7:00 Vajra Voices** page 54 early & chamber music contemporary & new music jazz & creative music ** Presidio Sessions Artists _ concert schedule page 63 2 . SFMusic Day 2016 LIVE + FREE 12 noon - 8:00pm 12:00 The String Quartet—The First 250 Years by Kai Christiansen page 8 12:30 St. -

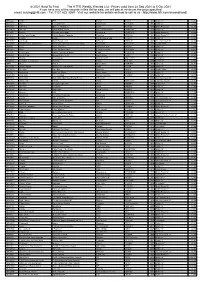

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

Electronic Music Midwest 13Th Annual Festival Providing Access to New

13th Annual Festival Electronic Music Midwest October 24-26, 2013 Kansas City Kansas Community College Providing access to new electroacoustic music by living composers October 24-26, 2013 Kansas City Kansas Community College Kansas City, Kansas October 24, 2013 Dear Friends, Welcome to the 13th Annual Electronic Music Midwest! We are truly excited about our opportunity to present this three-day festival of electroacoustic music. Over 200 works were submitted for consideration for this year’s festival. Congratulations on your selection! Since 2000, our mission has been to host a festival that brings new music and innovative technologies to the Midwest for our students and our communities. We present this festival to offer our students and residents a chance to interact and create a dialog with professional composers. We are grateful that you have chosen to help us bring these goals to fruition. We are grateful to Kari Johnson for serving as our artist in residence this year. Kari is an outstanding performer throughout the festival. The 2013 EMM will be an extraordinary festival. If only for a few days, your music in this venue will create a sodality we hope continues for a longtime to follow. Your contribution to this festival gives everyone in We are delighted that you have chosen to join us this year at EMM, and we hope that you have a great time during your stay. If we can do anything to make your experience here better, please do not hesitate to ask any of the festival team. Welcome to EMM! Mike, Jason, Jay, David, Rob, and Ian EMM Guest Artist, Kari Johnson “…Johnson played beautifully, displaying a !rm musicality and a "air for drama.” - Kansas City Star “…her sensitivities rather extraordinary, baroque while futuristic.” - www.acousticmusic.com Kari Johnson is a pianist who specializes in new music and electronic music performance. -

Genres, Stile Und Musikalische Strömungen Populärer Musik in Deutschland

Peter Wicke Genres, Stile und musikalische Strömungen populärer Musik in Deutschland Die populäre Musik hat sich in den letzten Jahrzehnten in eine unüberschaubare Vielfalt an Spielweisen und Stilformen ausdifferenziert. Dabei haben Genre- und Gattungsmodelle ihre normative Bindekraft verloren und einer im Prinzip grenzenlosen Individualisierung musikalischer Kreativität Raum gegeben. Andererseits liefern sie jedoch noch immer einen funktionellen Orientierungsrahmen für den Marketing-Prozess, der das ausufernde Angebot an Produktionen strukturiert und auf das Musikschaffen zurückwirkt. Der musikalische Inhalt der einschlägigen Begrifflichkeit hat sich dabei mit einer Vielzahl von außermusikalischen Aspekten – Nachfragestrukturen, Zielgruppen, Vertriebswegen, Kommunikationsstrategien, Medien- und Programm- formaten – verzahnt, die derartige Kategorien allenfalls noch als Grobraster tauglich machen. Hinter dieser Entwicklung haben sich zudem Musikformen wie etwa das unterhaltende Musiktheater in Form von Operet- te und Musical in ihren tradierten institutionellen Zusammenhängen behauptet, werden wie die Blasmusik und viele Laienmusikformen auf der Grundlage fester Traditionen erhalten oder sind wie die Film-, TV- und Werbemusik in eng definierte und damit relativ stabile Anwendungskontexte eingebunden, die je nach Be- trachtungsperspektive ebenfalls dem weiten Feld der populären Musik zuzuschlagen sind. Die Tatsache, dass es sich bei den einschlägigen Genre-Kategorien um reine Platzhalterbegriffe handelt, die weder stabile Zu- schreibungen -

Music Business in Detroit

October 18, 2013 Music Business in Detroit: Estimating the Size of the Music Industry in the Motor City Prepared by: Anderson Economic Group, LLC Colby Spencer Cesaro, Senior Analyst Alex Rosaen, Senior Consultant Lauren Branneman, Senior Analyst Forward by: Patrick L. Anderson, Principal & CEO Anderson Economic Group, LLC 1555 Watertower Place, Suite 100 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 Tel: (517) 333-6984 Fax: (517) 333-7058 www.AndersonEconomicGroup.com © Anderson Economic Group, LLC, 2013 Permission to reproduce in entirety granted with proper citation. All other rights reserved. Foreword I'm pleased to share with readers of Crain's Detroit Business, as well as with others in the Detroit region, this first-of-its-kind study of the business of music in southeast Michigan. Everyone that grew up in this area knows of the "Motown sound," as well as the heritage of jazz, blues, and rock that has steeped into our culture. Many of us are also aware of the more recent innovations of techno and hip-hop, much of which has roots in Detroit. However, until now there has been no systematic analysis of the business of music in our area. Our Anderson Economic Group consultants have combed census and other business records; examined the geographic pattern of nightclubs and perfor- mance venues; scanned demographic patterns for concentrations of heavy enter- tainment consumers; and even conducted primary research into the days/nights of live music available to metro Detroiters at over two hundred specific bars, taverns, and clubs. What we have assembled is a thorough analysis of an indus- try that has always been important to our culture, but can now also be known for its contributions to our employment and earnings. -

Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido

DESCUENTOS TIENDAS DE MUSICA 5 Unidades 3% CONSULTAR PRECIOS Y 10 Unidades 5% CONDICIONES DE DISTRIBUCION 20 Unidades 9% e-mail: [email protected] 30 Unidades 12% Tfno: (+34) 982 246 174 40 Unidades 15% LISTADO STOCK, actualizado 09 / 07 / 2021 50 Unidades 18% PRECIOS VALIDOS PARA PEDIDOS RECIBIDOS POR E-MAIL REFERENCIAS DISPONIBLES EN STOCK A FECHA DEL LISTADOPRECIOS CON EL 21% DE IVA YA INCLUÍDO Referencia Sello T Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido 3024-DJO1 3024 12" DJOSER - SECRET GREETING EP BASS NLD 14.20 AAL012 9300 12" EMOTIVE RESPONSE - EMOTIONS '96 TRANCE BEL 15.60 0011A 00A (USER) 12" UNKNOWN - UNTITLED TECHNO GBR 9.70 MICOL DANIELI - COLLUSION (BLACKSTEROID 030005V 030 12" TECHNO ITA 10.40 & GIORGIO GIGLI RMXS) SHINEDOE - SOUND TRAVELLING RMX LTD PURE040 100% PURE 10" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.60 (RIPPERTON RMX) BART SKILS & ANTON PIEETE - THE SHINNING PURE043 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 8.90 (REJECTED RMX) DISTRICT ONE AKA BART SKILS & AANTON PURE045 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.10 PIEETE - HANDSOME / ONE 2 ONE DJ MADSKILLZ - SAMBA LEGACY / OTHER PURE047 100% PURE 12" TECHNO NLD 9.00 PEOPLE RENATO COHEN - SUDDENLY FUNK (2000 AND PURE088 100% PURE 12" T-HOUSE NLD 9.40 ONE RMX) PURE099 100% PURE 12" JAY LUMEN - LONDON EP TECHNO NLD 10.30 DILO & FRANCO CINELLI - MATAMOSCAS EP 11AM002 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 (KASPER & PAPOL RMX) FUNZION - HELADO EN GLOBOS EP (PAN POT 11AM003 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 & FUNZION RMXS) 1605 MUSIC VARIOUS ARTISTS - EXIT PEOPLE REMIXES 1605VA002 12" TECHNO SVN 9.30 THERAPY (UMEK, MINIMINDS, DYNO, LOCO & JAM RMXS) E07 1881 REC. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

REVIEW ARTICLE James W. Heisig, Philosophers of Nothingness: an Essay on the Kyoto School University of Hawaii Press, 2001

PARRHESIA NUMBER 10 • 2010 • 87-92 REVIEW ARTICLE James W. Heisig, Philosophers of Nothingness: An Essay on the Kyoto School University of Hawaii Press, 2001 Eugene Thacker 1. DEATH IN DEEP SPACE There is a motif commonly found in science fiction, which derives from earlier narratives of nautical adven- ture and stories of castaways. The motif is that of the sole human being, unmoored, set loose, and adrift in space. One of the most popular versions of this is found in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which astronaut Frank Poole is set loose by the intelligent supercomputer HAL to drift aimlessly into the depths of deep space. In the film Kubrick portrays the scene without a soundtrack or, for that matter, any sound at all. The scene of being set adrift into space is depicted with silent horror: all we as viewers see is a lone figure speeding off into a black abyss. JAMES W. HEISIG, PHILOSOPHERS OF NOTHINGNESS During the Golden Age of science fiction in the 1920s and 1930s, pulp authors tended to depict the “adrift in space” motif as being “lost in space,” that is, as a by-product of inter-galactic adventure narratives. One was only lost in space until the next adventure, the next battle, the next conquest. However, for earlier works—most notably Camille Flammarion’s metaphysical science fiction Lumen—being adrift in space is less a by-way to yet another adventure, but a speculative opportunity in and of itself. Being adrift in space is the story itself, so much so that Edgar Allen Poe could pen entire cosmic dialogues around the theme, without character, plot, or setting.