Summer Assignment AP Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

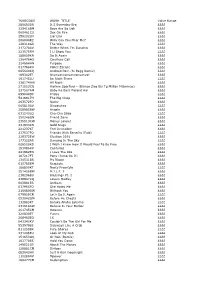

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Historical Archaeology and the Importance of Material Things

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE IMPORTANCE OF MATERIAL THINGS LELAND FERGUSON, Editor r .\ SPECIAL PUBLICATION SERIES, NUMBER 2 Society for Historical Archaeology Special Publication Series, Number 2 published by The Society for Historical Archaeology The painting on the cover of this volume was adapted from the cover of the 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue, publishedby Chelsea House Publishers, New York, New York, 1968. The Society for Historical Archaeology OFFICERS RODERICK SPRAGUE, University ofIdaho President JAMES E. AYRES, Arizona State Museum President-elect JERVIS D. SWANNACK, Canadian National Historic Parks & Sites Branch Past president MICHAEL J. RODEFFER, Ninety Six Historic Site Secretary-treasurer JOHN D. COMBES, Parks Canada ,,,, , , Editor LESTER A. Ross, Canadian National Historic Parks & Sites Branch Newsletter Editor DIRECTORS 1977 KATHLEEN GILMORE, North Texas State University LEE H. HANSON, Fort Stanwix National Monument 1978 KARLIS KARKINS, Canadian National Parks & Sites Branch GEORGE QUIMBY, University ofWashington 1979 JAMES E.. FITTING, Commonwealth Associates,Inc. DEE ANN STORY, Balcones Research Center EDITORIAL STAFF JOHN D. COMBES ,, Editor Parks Canada, Prairie Region, 114 Garry Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C IGI SUSAN JACKSON Associate Editor Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina 29208 JOHN L. COITER Recent Publications Editor National Park Service, 143South Third Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 WILLIAM D. HERSHEY , , Recent Publications Editor Temple University, Broad and Ontario, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 KATHLEEN GILMORE. ....................................................... .. Book Review Editor Institute for Environmental Studies, North Texas State University, Denton, Texas 76201 LESTER A. Ross Newsletter Editor National Historic Parks & Sites Branch, 1600Liverpool Court, Ottawa, Ontario, KIA OH4 R. DARBY ERD Art Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina. -

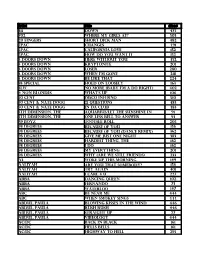

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Former JSU Athlete Makes AIDS Reality Mented Cases of AIDS in Calhoun County." and Vaginal Secretions

Vol. 39 No. 22 Jacksonville State University March 5,1992 Faculty question DSS gets division move positive review ments would be resurfacing the track Deborah Martin Petty of the Uni- Eric G. Mackey and building a new baseball field. Editor in Chief versity ofTennesseecommunicates Kennamer said he was not aware if with JSU's deaf students through there was a need for a softball field. the use of sign language. Petty JSU Trustee Bob Kennarner, though a report released earlier by visited JSU last week as part of a Anniston, met with the Faculty Sen- the athletic department called for one. peer review program with the ate to discuss the University's move JSU's present baseball field is con- Postsecondary Education Consor- to NCAA Division I Monday. sidered unsafe because of its loca- tium, which provided $65,000 for The senators asked Kennamer to tion. Kennamer helped halt the con- Disabled Student Services' pro- meet with them to answer prepared struction of a new facility several grams for the hearing impaired last questions which Kennamerreviewed years ago, but said he now under- year. The peerreview did not affect earlier and answered Monday. stands the problems of the current funding for disabled students, but Kennamer also took some spontane- location by Bennett Drive if a fly ball allowed the department the oppor- ous questions. were to hit a passing car. "I was in tunity to learn what it can do better, Most of the questions dealt with error when I stopped that process as well as what it does best.The the financial implicationsof themove. -

Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY By tommy symmes A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE William B Parsons William B Parsons (Apr 21, 2021 11:48 PDT) William Parsons Jeffrey Kripal Jeffrey Kripal (Apr 21, 2021 13:45 CDT) Jeffrey Kripal James Faubion James Faubion (Apr 21, 2021 14:17 CDT) James Faubion HOUSTON, TEXAS April 2021 1 Abstract This dissertation studies dance music events in a field survey of writings, in field work with interviews, and in conversations between material of interest sourced from the writing and interviews. Conversations are arranged around six reading themes: events, ineffability, dancing, the materiality of sound, critique, and darkness. The field survey searches for these themes in histories, sociotheoretical studies, memoirs, musical nonfiction, and zines. The field work searches for these themes at six dance music event series in the Twin Cities: Warehouse 1, Freak Of The Week, House Proud, Techno Tuesday, Communion, and the Headspace Collective. The dissertation learns that conversations that take place at dance music events often reflect and engage with multiple of the same themes as conversations that take place in writings about dance music events. So this dissertation suggests that writings about dance music events would always do well to listen closely to what people at dance music events are already chatting about, because conversations about dance music events are also, often enough, conversations about things besides dance music events as well. 2 Acknowledgments Thanks to my dissertation committee for reading this dissertation and patiently indulging me in conversations about dance music events. -

Most Requested Songs of 2015

Top 200 Most Requested Songs in the UK Based on thousands of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings/parties in 2015 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Williams, Pharrell Happy 3 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 4 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 5 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 6 Killers Mr. Brightside 7 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 8 ABBA Dancing Queen 9 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 10 Adams, Bryan Summer Of '69 11 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 12 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 13 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 14 Mars, Bruno Marry You 15 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 16 Daft Punk Feat. Pharrell Williams Get Lucky 17 B-52's Love Shack 18 Psy Gangnam Style 19 Dexy's Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 22 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 23 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 24 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 25 Outkast Hey Ya! 26 Trainor, Meghan All About That Bass 27 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 28 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 29 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Travolta, John & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 32 Omi Cheerleader 33 Avicii Wake Me Up! 34 Los Del Rio Macarena 35 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 36 House Of Pain Jump Around 37 One Direction What Makes You Beautiful 38 Medley, Bill & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life 39 Perry, Katy Firework 40 Maroon 5 Sugar 41 Sister Sledge We Are Family 42 Wonder, Stevie Superstition 43 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go 44 Legend, John All Of Me 45 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody 46 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

US Representations of the Male Body in Performance Art Monologues

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 Performing masculinities: U.S. representations of the male body in performance art monologues Darren C. Goins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goins, Darren C., "Performing masculinities: U.S. representations of the male body in performance art monologues" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2539. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2539 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PERFORMING MASCULINITIES: U.S. REPRESENTATIONS OF THE MALE BODY IN PERFORMANCE ART MONOLOGUES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Communication Studies by Darren C. Goins B.A., Emory University, 1994 M.A., Florida State University, 1997 August, 2004 To my family of origin and my chosen family who have shaped my performance of masculinity. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank those individuals whose cooperation and guidance made the successful completion of this project possible. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Ruth Laurion Bowman, for her wisdom, patience, attention, faith, and energy. Next, I would like to thank Dr. -

Music List (PDF)

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU -

Record of the Week

ISSUE 636 / 16 JULY 2015 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Germany first-half Summer See page 12 music sales rise 4.5%. for contact (Billboard) Aufgang details Blue Note France } Neil Young withdraws July 17 from streaming Aufgang is a critically acclaimed French pop duo, hugely services over influenced by the incredible underground disco and synth pop poor audio quality. sounds of New York in the 1980s. Rami and Aymeric met whilst in Beirut, Paris and NYC) sees them drawing on their French/ CONTENTS (Facebook) studying piano at the prestigious Julliard School in Manhattan Lebanese backgrounds for a rather unique blend of indie pop, and that classical training shines through here in the intricate electronica and pre-modern Arabic sounds. This great track } Berklee College keyboard flourishes and string arrangements that underpin this has been mixed by Michael Brauer, noted for his work with P2 Editorial: David report criticises music gloriously funky little pop nugget. Both guys have collaborated acts including Coldplay, Sade and Florence & The Machine. Balfour on the industry for lack with the likes of Cassius and Phoenix and their forthcoming Summer’s here, fling the windows open and get ready to sing Rethink Music of transparency. album (due for release next year and currently being recorded your head off to this, undoubtedly with a huge grin on your face. transparency report (Billboard) P4 Interview: LWE discuss promoting } HMV planning in London international expansion. (Telegraph) P6 Compass p8 Gossip and Sony Music } observations asserts right to from Mongrel strike deals which ‘disadvantage’ artists. p16 The week’s best P4 London Warehouse Events P6 Compass: Oslo Parks P11 Records of the Week: Radio (HollywoodReporter) comment pieces Plus all the regulars WORLDWIDE SALES including 6am, Word On, Business News, MARKETING AND Media Watch and DISTRIBUTION Chart Life 1 editorial There are many valid points raised in the Rethink Music transparency report, David Balfour comments, though it’s also quite unbalanced in places. -

1. SF35001 Taylor Swiftанаstyle 2. SF35002 Ed Sheeran & Rudimental

1. SF35001 Taylor Swift Style 2. SF35002 Ed Sheeran & Rudimental Bloodstream 3. SF35003 Florence & The Machine What Kind Of Man 4. SF35004 Royal Blood Out Of The Black 5. SF35005 Usher & Juicy J I Don't Mind 6. SF35006 Carly Rae Jepsen I Really Like You 7. SF35007 Rihanna Towards The Sun 8. SF35008 Alex Adair Make Me Feel Better 9. SF35009 Flo Rida & Sage The Gemini & Lookas GDFR 10. SF35010 Vaccines Handsome 11. SF35011 Jess Glynne Hold My Hand 12. SF35012 Conor Maynard Talking About 13. SF35013 Kanye West & Theophilus London & Allan Kingdom & Paul McCartney All Day 14. SF35014 Pitbull & NeYo Time Of Our Lives 15. SF35015 Olly Murs Seasons 16. SF35016 Philip George Wish You Were Mine 17. SF35017 Madonna Ghosttown 18. SF35018 Van Morrison & Michael Buble Real Real Gone 19. SF35101 Wiz Khalifa ft Charlie Puth See You Again 20. SF35102 Mumford & Sons Believe 21. SF35103 Iggy Azalea ft Jennifer Hudson Trouble 22. SF35104 Sam Smith ft John Legend Lay Me Down 23. SF35105 Tough Love So Freakin' Tight 24. SF35106 Lunchmoney Lewis Bills 25. SF35107 Muse Dead Inside 26. SF35108 Blonde ft Alex Newell All Cried Out 27. SF35109 Jason Derulo Want To Want Me 28. SF35110 Electro Velvet Still In Love With You 29. SF35111 Clean Bandit Stronger 30. SF35112 Kodaline The One 31. SF35113 Major Lazer ft Mo & DJ Snake Lean On 32.