Who Was John Sampson Really Protecting?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call for Films

CALL FOR FILMS To all Roma, Sinti, Kale, Kalderash, Lovara, Lalleri, Ursari, Beasch, Manouches, Ashkali, Aurari, Romanichals, Droma, Doma, Gypsies, Travellers and all the other Romani groups of the world… The fourth Festival of Romani Film will take place in Berlin in 2020: AKE DIKHEA? Festival of Romani Film 19 – 23 November 2020 We are looking for films with which members of different Romani groups can identify to. People with a Romani background or self-organizations can propose films by Roma and non-Roma filmmakers whose themes concern the lives of Romani people in the world and critically reflect upon the reality of discrimination. Possibilities of film registration: FilmFreeWay: https://filmfreeway.com/AkeDikhea Form: https://bit.ly/2NiDumj E-mail: [email protected] Deadline for submission of proposals: Sunday, 9 August 2020 Background information: AKE DIKHEA? translated means “YOU SEE?". It is a self-organized, international festival of Romani film that will take place in Berlin in November 2020. The festival presents Berlin, Germany and the whole world from the perspective of Romani people: Which films represent us, which themes are important to us, how do we see ourselves and how do we want to be seen? We don't want to wait until someone gives us a voice. We want to shape the social space ourselves and decide on the themes and structure of the festival events. The festival is organized by the Berlin Roma self-organization RomaTrial in cooperation with Germany's oldest cinema, Moviemento. Further information can be found on the roma-filmfestival.com website. Selection process The AKE DIKHEA? Festival of Romani Film stands for a unique, participatory selection process: Thanks to our worldwide network of (Romani) filmmakers, we are able to discover topics, people and perspectives that would otherwise remain hidden or only have a local or national impact. -

'Race' and Diaspora: Romani Music Making in Ostrava, Czech Republic

Music, ‘Race’ and Diaspora: Romani Music Making in Ostrava, Czech Republic Melissa Wynne Elliott 2005 School of Oriental and African Studies University of London PhD ProQuest Number: 10731268 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731268 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis is a contribution towards an historically informed understanding of contemporary music making amongst Roma in Ostrava, Czech Republic. It also challenges, from a theoretical perspective, conceptions of relationships between music and discourses of ‘race’. My research is based on fieldwork conducted in Ostrava, between August 2003 and July 2004 and East Slovakia in July 2004, as well as archival research in Ostrava and Vienna. These fieldwork experiences compelled me to explore music and ideas of ‘race’ through discourses of diaspora in order to assist in conceptualising and interpreting Romani music making in Ostrava. The vast majority of Roma in Ostrava are post-World War II emigres or descendants of emigres from East Slovakia. In contemporary Ostrava, most Roma live on the socio economic margins and are most often regarded as a separate ‘race’ with a separate culture from the dominant population. -

(CCJ) International Roma

ADVISORY COUNCIL ON YOUTH (CCJ) 8 April 2021 English only International Roma Day On International Roma Day, 8 April, the Advisory Council on Youth sends its warm wishes to Roma and Travellers1 communities across Europe. International Roma Day recognises and celebrates Romani history and culture but also pays tribute to the work and great achievements of the Roma Movement and Romani activists over the decades. Fifty years ago, on this day, the Roma Movement held the First World Romani Congress in Orpington, England (UK). The Congress has become a part of Roma history, several significant decisions were made, which have had an identity-forming impact on Roma communities, such as the adoption of the song “Gelem, Gelem” as the official Romani anthem and the creation of a common flag. The choice of the terms “Rom” and “Romani” as official designations was to eliminate old prejudices and help create a new self-confidence.2 The Advisory Council on Youth welcomes the recently adopted Recommendation CM/Rec(2020)2 on the inclusion of the history of Roma and/or Travellers in school curricula and teaching materials. The recommendation represents a timely agreement among the member states, that Romani history is part of European and national histories and provides an opportunity, for the marginalised Roma communities, to nurture their own culture and values in an institutionalised system. The Advisory Council on Youth invites the Council of Europe member states to commit to the implementation of this recommendation, and to the provision of adequate support to all relevant stakeholders in this process. Structural discrimination against Roma persists, however, rendering it extremely difficult for young Roma to access their rights, including social and civic rights. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Europe's Poverty-Stricken Roma Communities

EUROPE’S POVERTY-STRICKEN ROMA COMMUNITIES Askold Krushelnyck The next few years will be crucial for the Roma people. There are at least 6 million Roma in Europe with the majority in former communist countries, several of which joined the European Union (EU) in May 2004. Roma people hope that the tolerance espoused by the EU will break a centuries-long cycle of prejudice and persecution. Romania, scheduled to join the EU in 2007, has Europe’s largest Roma population of around 2million people. But the name Roma is not derived from Romania, where they were enslaved until 1864. The Nazis slaughtered between 500,000 and 1.5 million Roma in a little known holocaust. The Roma, or Romani (meaning ‘man’ or ’people’), have also been called Gypsies, Tsigani, Tzigane, Ciganoand Zigeuner, which most of them consider derogatory terms. Many identify themselves by their tribes and groups, which include the Kalderash, Machavaya, Lovari, Churari, Romanichal, Gitanoes, Kalo, Sinti, Rudari, Manush, Boyash, Ungaritza, Luri, Bashaldé, Romungroand Xoraxai. There is no universal Roma culture, although there are attributes common to all Roma: Roma populations have the poorest education, health and employment opportunities, and the highest rates of imprisonment and welfare dependency. They have the lowest life expectancy levels of all Europeans. They also have the highest birthrate, giving credibility to evidence that authorities in one Central European country were recently pressuring Roma women to undergo sterilization. The Roma still have a reputation as nomadic peoples; but the nomadic lifestyle owed as much to Roma people being banned from entering towns as to any desire to wander. -

Download Booklet

Heavenly Harp BEST LOVED classical harp music Heavenly Harp Best loved classical harp music 1 Alphonse HASSELMANS (1845–1912) 10 Henriette RENIÉ (1875–1956) La Source, Op. 44 3:55 Danse des Lutins 3:59 Erica Goodman (8.573947) Judy Loman (8.554347) 2 Hugo REINHOLD (1854–1935) 11 Marcel TOURNIER (1879–1951) Impromptu in C sharp minor, Op. 28, No. 3 5:35 Vers la source dans le bois 4:18 Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) (‘Towards the Fountain in the Wood’) Judy Loman (8.554561) 3 John THOMAS (1826–1913) Dyddiau Mebyd (‘Scenes of Childhood’) – 3:05 12 Gabriel FAURÉ (1845–1924) II. Toriad y Dydd (‘The Dawn of Day’) Une chatelaine en sa tour, Op. 110 4:41 Lipman Harp Duo (8.570372) Judy Loman (8.554561) 4 Gaetano DONIZETTI (1797–1848) 13 Elias PARISH ALVARS (1808–1849) Lucia di Lammermoor, Act 1 Scene 2 4:25 Serenade, Op. 83 – Serenade 7:13 (arr. A.H. Zabel) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) 14 Gabriel PIERNÉ (1863–1937) 5 Marcel GRANDJANY (1891–1975) Impromptu-caprice, Op. 9 5:51 Fantasy on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 31 7:54 Ellen Bødtker (8.555328) Judy Loman (8.554561) 15 Nino ROTA (1911–1979) 6 Manuel de FALLA (1876–1946) Toccata 2:33 La vida breve, Act II – 4:11 Elisa Netzer (8.573835) Danse espagnole No. 1 (ver. For 2 guitars) Judy Loman (8.554561) 16 John PARRY (1710–1782) Sonata No. 2 – Siciliana 2:06 7 Sophia DUSSEK (1775–1847) Judy Loman (8.554347) Sonata – Allegro 2:39 Judy Loman (8.554347) 17 Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH (1714–1788) 12 Variations on La folia d’Espagne, 9:13 8 Louis SPOHR (1784–1859) Wq. -

Challenging Essentialized Representations of Romani Identities in Canada

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-7-2014 12:00 AM Challenging Essentialized Representations of Romani Identities in Canada Julianna Beaudoin The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Randa Farah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Julianna Beaudoin 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Beaudoin, Julianna, "Challenging Essentialized Representations of Romani Identities in Canada" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1894. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1894 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Challenging Essentialized Representations of Romani Identities in Canada (Thesis format: Monograph) by Julianna Calder Beaudoin Graduate Program in Anthropology Collaborative Program in Migration and Ethnic Relations A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada ©Julianna Beaudoin 2014 Abstract Roma are one of the world’s most marginalized and exoticized ethnic groups, and they are currently the targets of increasing violence and exclusionary polices in Europe. In Canada, immigration and refugee policies have increasingly dismissed Roma as illegitimate or ‘bogus’ refugee claimants, in large part because they come from ‘safe’ European countries. -

European Roma Grassroots Organisations (Ergo) Network

EUROPEAN ROMA GRASSROOTS ORGANISATIONS (ERGO) NETWORK How to ensure that the European Pillar of Social Rights delivers on Roma equality, inclusion, and participation? Introduction On 17 November 2017, the European Union broke new ground by adopting the European Pillar of Social Rights (Social Pillar), the first set of social rights proclaimed by EU institutions since the Charter of Fundamental Rights in the year 2000. While not legally binding, this comprehensive initiative of 20 social policy principles, complemented by a Social Scoreboard of 14 indicators, aims at supporting well-functioning and fair labour markets and welfare systems, with a focus on better integrating and delivering on social concerns. The European Commission has pledged to make the Social Pillar “the compass of Europe’s recovery and our best tool to ensuring no one is left behind”1, so that Europe’s future is socially fair and just. This paper sets out ERGO Network’s analysis and policy recommendations so that the implementation of the Social Pillar does not leave the European Roma2 behind. It builds on the direct experience of our national members on the ground, and it aims to draw positive reinforcing links between the Social Pillar and the recently adopted EU Strategic Framework for Roma Equality, Participation, and Inclusion. Delivery on the latter must, in turn, be fully integrated in the European Semester, and work in synergy with other key economic and social processes, such as the European Pillar of Social Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals. These must be mutually reinforcing processes. Unfortunately, the EU Roma Strategic Framework targets makes few specific links to the Social Pillar and its 20 principles, and a footnote even reduces the scope to only 3 principles. -

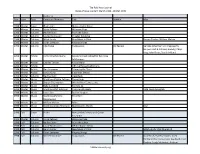

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998 Author or Year Issue Type Composer/Arranger Title Subtitle Misc 1998 Winter Cover Illustration Make a Joyful Noise 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Winter Column Laurie Rasmussen Chapter Roundup 1998 Winter Column Mitch Landy New Music in Print Harper Tasche; William Mahan 1998 Winter Column Dinah LeHoven Ringing Strings 1998 Winter Column Alys Howe Harpsounds CD Review Verlene Schermer; Lori Pappajohn; Harpers Hall & Culinary Society; Chrys King; John Doan; David Helfand 1998 Winter Article Patty Anne McAdams Second annual retreat for Bay Area folk harpers 1998 Winter Article Charles Tanner A Cool Harp! 1998 Winter Article Fifth Gulf Coast Celtic harp 1998 Winter Article Ann Heymann Trimming the Tune 1998 Winter Article James Kurtz Electronic Effects 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn Classifieds 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Sylvia Fellows Three Kings 1998 Winter Music Sharon Thormahlen Where River Turns to sky 1998 Winter Music Reba Lunsford Tootie's Jig 1998 Winter Music Traditional/M. Schroyer The Friendly Beats 12th Century English 1998 Winter Music Joyce Rice By Yon Yangtze 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Serena He is Born Underwood 1998 Winter Music William Mahan Adios 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Ann Heymann MacDonald's March Irish 1998 Fall Cover Photo New Zealand's Harp and Guitar Ensemble 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Fall Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Fall Column -

Romani | Language Roma Children Council Conseil of Europe De L´Europe in Europe Romani | Language

PROJECT EDUCATION OF ROMANI | LANGUAGE ROMA CHILDREN COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE IN EUROPE ROMANI | LANGUAGE Factsheets on Romani Language: General Introduction 0.0 Romani-Project Graz / Dieter W. Halwachs The Roma, Sinti, Calè and many other European population groups who are collectively referred to by the mostly pejorative term “gypsies” refer to their language as Romani, Romanes or romani čhib. Linguistic-genetically it is a New Indo-Aryan language and as such belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. As an Indo-Aryan diaspora language which occurs only outside the Indian subcontinent, Romani has been spoken in Europe since the Middle Ages and today forms an integral part of European linguistic diversity. The first factsheet addresses the genetic and historical aspects of Romani as indicated. Four further factsheets cover the individual linguistic structural levels: lexis, phonology, morphology and syntax. This is followed by a detailed discussion of dialectology and a final presentation of the socio-linguistic situation of Romani. 1_ ROMANI: AN INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE OF EUROPE deals with the genetic affiliation and with the history of science and linguistics of Romani and Romani linguistics. 2_ WORDS discusses the Romani lexicon which is divided into two layers: Recent loanwords from European languages are opposed by the so-called pre-European inherited lexicon. The latter allowed researchers to trace the migration route of the Roma from India to Europe. 3_ SOUNDS describes the phonology of Romani, which includes a discussion of typical Indo-Aryan sounds and of variety- specific European contact phenomena. THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN THIS WORK ARE THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AUTHORS AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE OFFICIAL POLICY OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE. -

Contribution Au Glossaire Sur Les Roms

1 HDIM.IO/218/07 27 September 2007 ORIGINAL: English Roma and Travellers Glossary Compiled by Claire PEDOTTI (French Translation Department) and Michaël GUET (DGIII Roma and Travellers Division) in consultation with the English and French Translation Departments and Aurora AILINCAI (DGIV Project «Schooling for Roma Children in Europe»). Kindly translated into English by Vincent NASH (English Translation Department). General comments: The many different terms found in Council of Europe texts and on Council websites make harmonisation of the Organisation’s usage essential. That is the purpose of this glossary, which will be up-dated regularly . This glossary reflects the current consensus. Following its suggestions is thus strongly recommended (if in doubt, use the underlined term). Last update : 11 December 2006 2 The terminology used by the Council of Europe (CoE) has varied considerably since the early 1970s : «Gypsies and other travellers»1, «nomads»2, « populations of nomadic origin»3, «Gypsies»4, «Rroma (Gypsies)»5, «Roma»6, « Roma/Gypsies»7, «Roma/Gypsies and Travellers»8, « Roms et Gens du voyage »9. Some of our decisions on terminology are based on the conclusions of a seminar held at the Council of Europe in September 2003 on «The cultural identities of Roma, Gypsies, Travellers and related groups in Europe», which was attended by representatives of the various groups in Europe (Roma, Sinti, Kale, Romanichals, Boyash, Ashkali, Egyptians, Yenish, Travellers, etc.) and of various international organisations (OSCE-ODIHR, European Commission, UNHCR and others). The question’s complexity has obliged us to lay down a number of linguistic principles, which may seem a little arbitrary. -

Romani Realities in the US: Breaking the Silence

Romani Realities in the US: Breaking the Silence. Challenging the Stereotype. About the Study: The FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University and Voice of Roma are collaborating on a study of Romani (i.e., Roma/Romani/Romanichal/ “Gypsy”) lives in the United States. The research team will collect data to help improve the understanding of the social, economic, cultural, and health status of Romani people and the discrimination Romani people face in the United States. Currently, there is little information about the lived realities and challenges faced by the American Romani population. Romani people in the US are spread widely, and census data does not include information on Romani identity. This study will collect quantitative and qualitative data via short answers plus open-ended questions. The findings in this study will hopefully inspire and encourage more research on Romani populations across the Americas, counter stereotypes, and begin to address the problems that Romani people face. Those taking part in the study will be Roma/Romani/Romanichals who are 18 years or older. Participants will be asked for their opinion on how Roma/Romani/Romanichals/ “Gypsies” are depicted in the United States. Most of the questions are about Romani identity, culture, and participants’ feelings on some of the challenges facing their communities. The interview will take about 1 hour to complete and will be done through face-to-face interviews or via online video calling platforms. The researcher will not ask participants’ last names or any identifying personal data, such as indication of housing location. All responses to interview questions are private.