Forests &Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SNH Commissioned Report 449B: Bryological Assessment For

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 449b Bryological assessment for hydroelectric schemes in the West Highlands (2nd edition) COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 449b Bryological assessment for hydroelectric schemes in the West Highlands (2nd edition) For further information on this report please contact: Dr David Genney Policy & Advice Officer - Bryophytes, Fungi and Lichens Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road Inverness, IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725000 Email: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Averis, A.B.G., Genney, D.R., Hodgetts, N.G., Rothero, G.P. & Bainbridge, I.P. (2012). Bryological assessment for hydroelectric schemes in the West Highlands – 2nd edition. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No.449b This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2012. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Bryological assessment for hydroelectric schemes in the West Highlands – 2nd edition Commissioned Report No.: Report No. 449b Project No.: 10494 Contractor: A.B.G. Averis Year of publication: 2012 Background Proposals for run-of-river hydroelectric schemes are being submitted each year, but developers and planning consultees are often unclear about when to commission a bryophyte survey as part of the information submitted in a planning application. This project was commissioned by SNH to provide a means of assessing the bryological importance and/or potential of watercourses. This will help to clarify whether a survey is needed for any particular hydroelectric proposal. -

A Revised Red List of Bryophytes in Britain

ConservationNews Revised Red List distinguished from Extinct. This Red List uses Extinct in the Wild (EW) – a taxon is Extinct version 3.1 of the categories and criteria (IUCN, in the Wild when it is known to survive only in A revised Red List of 2001), along with guidelines produced to assist cultivation or as a naturalized population well with their interpretation and use (IUCN, 2006, outside the past range. There are no taxa in this 2008), further guidelines for using the system category in the British bryophyte flora. bryophytes in Britain at a regional level (IUCN, 2003), and specific Regionally Extinct (RE) – a taxon is regarded guidelines for applying the system to bryophytes as Regionally Extinct in Britain if there are no (Hallingbäck et al., 1995). post-1979 records and all known localities have Conservation OfficerNick Hodgetts presents the latest revised Red List for How these categories and criteria have been been visited and surveyed without success, or interpreted and applied to the British bryophyte if colonies recorded post-1979 are known to bryophytes in Britain. Dumortiera hirsuta in north Cornwall. Ian Atherton flora is summarized below, but anyone interested have disappeared. It should be appreciated that in looking into them in more depth should regional ‘extinction’ for bryophytes is sometimes he first published Red List of et al. (2001) and Preston (2010), varieties and consult the original IUCN documents, which less final than for other, more conspicuous bryophytes in Britain was produced subspecies have been disregarded. are available on the IUCN website (www. organisms. This may be because bryophytes are in 2001 as part of a Red Data Book 1980 has been chosen as the cut-off year to iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories- easily overlooked, or because their very efficient for bryophytes (Church et al., 2001). -

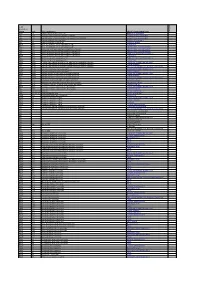

A Revised List of Nationally Rare Bryophytes

ConservationNews Revised list of nationally rare bryophytes v Timmia megapolitana. Ron Porley Committee, revises the list of nationally rare Table 1. Species now recorded in more than 15 10-km squares since 1950 species. It is a companion to the earlier revision A revised of scarce species (Preston, 2006) which provides H, hornwort; L, liverwort; M, moss. more background to the use of these terms. Atlas total Current total % of Atlas total The starting point for this revision is the list of nationally rare bryophyte species and subspecies H Phaeoceros carolinianus 4 17 425 list of L Barbilophozia kunzeana 10 17 170 which can be extracted from the spreadsheet of Conservation Designations for UK taxa on the L Fossombronia fimbriata 10 17 170 nationally Joint Nature Conservation Committee’s (JNCC) L Leiocolea fitzgeraldiae – 22 – website (www.jncc.gov.uk). I have brought the L Leiocolea gillmanii 13 18 138 taxonomy into line with that of the new Census L Lophozia perssonii 12 23 192 rare Catalogue (Hill et al., 2008), and updated the L Nardia breidleri 11 20 182 list to include newly discovered taxa and new L Scapania curta 15 16 107 10-km square records. The 10-km square totals L Scapania paludicola 4 19 475 bryophytes are based on records made from Britain (v.-cc. L Scapania paludosa 14 22 157 1–112) from 1950 onwards. M Bryum gemmilucens 10 20 200 The changes to the list are summarized below M Bryum knowltonii 13 19 146 and a complete new list of nationally rare species Chris Preston presents a M Bryum kunzei 8 16 200 then follows. -

Pohlia-Arten Der Schweiz Bestimmungsschlüssel Für Sterile Pflanzen

Pohlia-Arten der Schweiz Bestimmungsschlüssel für sterile Pflanzen zusammengestellt von Heiner Lenzin am 16. Januar 2019 nach dem Bestimmungsschlüssel von Gisela Nordhorn-Richter (1986) und den Unterlagen von Frank Müller für den Kurs vom 24./25.11.2018 (zusammengestellt aus den Quellen: Guerra 2007, Ignatov & Ignatova 2003, Köckinger in Swissbryophytes.ch, Köckinger et al. 2005, Liu et al. 2018, Meinunger & Schröder 2007, Nordhorn-Richter 1982, Nyholm 1993, Rothero 2014, Suarez et al. 2011, Shaw 1981, 1982, Shaw 2014 in Flora of North America 28, Smith 2004, Warnstorf 1906) und unter Verwendung von Nebel (2001). à s. Literaturverzeichnis Achtung: Schlüssel ohne Pohlia atropurpurea (Skandinavien, Russland), P. bolanderi (LESQ.) BROTH. (Spanien, Portugal, Madeira), P. scotica CRUNDW. (Schottland) und P. erecta LINDB. (Finnland, Norwegen, Schweden) 1. Pflanzen mit Bulbillen in den Achseln der Blättchen. ................................................. 2 – Pflanzen ohne Bulbillen in den Achseln der Blättchen. ............................................... 15 2. Bulbillen meist einzeln in den Achseln der Blättchen (selten mehr als 3), ei- bis kegelförmig, grün oder rot, gelb-orange bis schwarz, oft > 500 µm gross. ................. 3 – Mehr als eine Bulbille in den Achseln der Blättchen, z. T. an der Stämmchenspitze gehäuft, eiförmig oder länglich bis wurmförmig, grün, gelb-orange bis rot oder bräunlich, 50–400(–500) µm gross, die wurmförmigen schmal und oft viel länger werdend. ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Blättchen der Bulbillen klein und unscheinbar, an der Spitze der Bulbillen stark zusammengezogen („Krönchen“) P. filum (SCHIMP.) MART. -- Faden-Pohlmoos – Pflanzen bis 5 cm hoch. Bulbillen gelb-orange, selten rot, im Alter schwarz werdend, dann glänzend; 300–600 µm lang. Die Blättchen der sterilen Pflanzen gerade, auch trocken dem Stämmchen eng anliegend, der Pflanze oft ein fadenförmiges Aussehen gebend. -

List of UK BAP Priority Non-Vascular Plant Species (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Non-Vascular Plant Species (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Non-Vascular Plant Species (2007) A list of UK BAP priority non-vascular plant species, created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report, published in 2007, is provided in the table below. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Scientific name Common Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK name Ireland BAP species? Acaulon triquetrum Triangular bryophyte Y N N N Yes – SAP Pygmy-moss Acrobolbus wilsonii Wilson's bryophyte N Y N N Yes – SAP Pouchwort Adelanthus Lindenberg's bryophyte N Y N N Yes – SAP lindenbergianus Featherwort Anastrophyllum Joergensen's bryophyte N Y N N joergensenii Notchwort Andreaea nivalis Snow Rock- bryophyte N Y N N moss Anomodon Long-leaved bryophyte Y Y Y N longifolius -

Lead Ecosystem Group Code SBL Habitat Name UKBAP Priority

Lead Ecosystem Group code SBL Habitat name UKBAP Priority habitat name Category M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L CG2 Festuca ovina-Helictotrichon pratense grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 F&L CG7 Festuca ovina-Hieracium pilosella-Thymus polytrichus grassland Lowland calcareous grassland 1 M&C H7 Calluna vulgaris-Scilla verna heath Maritime cliff and slopes 3 F&L H8 Calluna vulgaris-Ulex gallii heath Lowland heathland 2 F&W M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Lowland fens 1 F&L M13 Schoenus nigricans-Juncus subnodulosus mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M21 Narthecium ossifragum-Sphagnum papillosum valley mire Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Upland flushes, fens and swamps 3 F&L M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M23 Juncus effusus/acutiflorus-Galium palustre rush-pasture Lowland fens 1 F&L M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Purple moor grass and rush pastures 2 F&W M26 Molinia caerulea-Crepis paludosa fen Lowland fens 1 F&W MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh 3 M&C MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Coastal saltmarsh 3 F&L MG11 Festuca rubra-Agrostis stolonifera-Potentilla anserina inundation grassland Open mosaic habitats on previously developed land 3 F&W MG12 Festuca arundinacea coarse grassland Coastal -

OPP DOC.19.21 Current OMEGA WEST RAW DATA

Total Taxon group Common name Scientific name Designation code Designation group 0 LICHEN Buellia hyperbolica Buellia hyperbolica IUCN Global Red List - Vulnerable, Nationally Rare, NERC S41, UK BAP Priority Species European/National Importance,European and UK Legal Protection 0 LICHEN Lecidea mucosa Lecidea mucosa Nationally Rare European/National Importance 0 FLOWERING PLANT Keeled Garlic Allium carinatum Invasive Non-Native Species Invasive Non-Native 0 LICHEN Micarea submilliaria Micarea submilliaria Nationally Rare European/National Importance 0 CHROMIST Macrocystis pyrifera Macrocystis pyrifera Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 European and UK Legal Protection 0 CHROMIST Macrocystis laevis Macrocystis laevis Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 European and UK Legal Protection 0 FLOWERING PLANT Indian Balsam Impatiens glandulifera Invasive Non-Native Species, Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 Invasive Non-Native,European and UK Legal Protection 0 FLOWERING PLANT False-acacia Robinia pseudoacacia Invasive Non-Native Species, Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 Invasive Non-Native,European and UK Legal Protection 0 FLOWERING PLANT Giant Hogweed Heracleum mantegazzianum Invasive Non-Native Species, Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 Invasive Non-Native,European and UK Legal Protection 0 CHROMIST Macrocystis integrifolius Macrocystis integrifolius Wildlife and Countryside Act Schedule 9 European and UK Legal Protection 0 CHROMIST Macrocystis augustifolius Macrocystis augustifolius Wildlife and Countryside Act -

Chapter 12 Bryophytes

Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs Part 2: Detailed Guidelines for Habitats and Species Groups Chapter 12 Bryophytes Authors Sam Bosanquet, David Genney and Jonathan Cox To view other Part 2 chapters and Part 1 of the SSSI Selection Guidelines visit: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2303 Cite as: Bosanquet, S.D.S., Genney, D.R. and Cox, J.H.S. 2018. Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs. Part 2: Detailed Guidelines for Habitats and Species Groups. Chapter 12 Bryophytes. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. © Joint Nature Conservation Committee 2018 Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs - Part 2: Chapter 12 Bryophytes (2018 revision, v1.0) Cover note This chapter updates and, along with Chapter 13 Lichens and Chapter 14 Non-lichenised fungi, replaces the previous Non-vascular plants SSSI Selection Guidelines chapter (Nature Conservancy Council 1992). It was prepared by Sam Bosanquet (Natural Resources Wales), Jonathan Cox (Natural England) and David Genney (Scottish Natural Heritage), and provides detailed guidance for use in selecting bryophyte sites throughout Great Britain to recommend for notification as SSSIs. It should be used in conjunction with Part 1 of the SSSI Selection Guidelines, as published in 2013 (Bainbridge et al 2013), which detail the overarching rationale, operational approach and criteria for selection of SSSIs. The main changes from the previous version of the chapter are: • only bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) are considered; • assemblage scoring is based on ecologically coherent assemblages; • scores for Nationally Scarce species are constant across Britain; • two Atlantic assemblages have scoring systems that include non-Scarce Hyperoceanic species; • a criterion for selecting the largest population of Red List species in each of England, Scotland and Wales is included; and • discontinuation of the Schedule 8 species selection criterion. -

UK BAP Priority Habitat Descriptions

UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Habitat Descriptions UK Biodiversity Action Plan; Priority Habitat Descriptions. BRIG (ed. Ant Maddock) 2008. (Updated Dec 2011) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit http://www.jncc.gov.uk/page-5155 Contents UK BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN: PRIORITY HABITAT DESCRIPTIONS INTRODUCTION 1 HABITAT DESCRIPTIONS 2 Aquifer Fed Naturally Fluctuating Water Bodies 2 Arable Field Margins 3 Blanket Bog 4 Blue Mussel Beds on Sediment 6 Calaminarian Grasslands 8 Carbonate Mounds 9 Coastal and Floodplain Grazing Marsh 10 Coastal Saltmarsh 10 Coastal Sand Dunes 12 Coastal Vegetated Shingle 13 Cold-water Coral Reefs 14 Deep-sea Sponge Communities 16 Estuarine Rocky Habitats 18 Eutrophic Standing Waters 21 File Shell Beds 22 Fragile Sponge and Anthozoan Communities on Subtidal Rocky Habitats 23 Hedgerows 25 Horse Mussel Beds 25 Inland Rock Outcrop and Scree Habitats 27 Intertidal Underboulder Communities 28 Intertidal Chalk 30 Intertidal Mudflats 31 Limestone Pavements 33 Lowland Beech and Yew Woodland 33 Lowland Calcareous Grassland 34 Lowland Dry Acid Grassland 34 Lowland Fens 36 Lowland Heathland 36 Lowland Meadows 37 Lowland Mixed Deciduous Woodland 38 Lowland Raised Bog 39 Machair 40 Maerl Beds 41 Maritime Cliff and Slopes 42 Mesotrophic Lakes 44 Mountain Heaths and Willow Scrub 45 Mud Habitats in Deep Water 46 Native Pine Woodlands 47 Oligotrophic and Dystrophic Lakes 48 i Open Mosaic Habitats on Previously Developed Land 49 Peat and Clay Exposures with Piddocks 57 Ponds 59 Purple -

SBL: Algae, Mosses, Liverworts & Stoneworts

Scottish Biodiversity List: Algae, Liverworts, Mosses & Stoneworts Taxonomic Scientific Name Common Name Distribution Map Group alga Actinotaenium NBN Atlas Map adelochondrum alga Actinotaenium clevei NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium colpopelta NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium cucurbitinum NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium curtum NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium gelidum NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium perminutum NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium rufescens NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium silvae-nigrae NBN Atlas Map alga Actinotaenium turgidum NBN Atlas Map alga Batrachospermum NBN Atlas Map gelatinosum spermatoinvolucrum alga Closterium anguineum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium archerianum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium calosporum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium didymotocum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium limneticum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium lineatum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium navicula NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium nematodes NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium pritchardianum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium pygmaeum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium subscoticum NBN Atlas Map alga Closterium toxon NBN Atlas Map alga Coelastropsis costata NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium alpestre NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium binum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium bioculatum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium carinthiacum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium conspersum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium crenulatum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium cucumis NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium cyclicum NBN Atlas Map alga Cosmarium dentiferum NBN Atlas Map Scottish Biodiversity List: Algae, Liverworts, Mosses & -

2447 Introductions V3.Indd

BRYOATT Attributes of British and Irish Mosses, Liverworts and Hornworts With Information on Native Status, Size, Life Form, Life History, Geography and Habitat M O Hill, C D Preston, S D S Bosanquet & D B Roy NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and Countryside Council for Wales 2007 © NERC Copyright 2007 Designed by Paul Westley, Norwich Printed by The Saxon Print Group, Norwich ISBN 978-1-85531-236-4 The Centre of Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) is one of the Centres and Surveys of the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). Established in 1994, CEH is a multi-disciplinary environmental research organisation. The Biological Records Centre (BRC) is operated by CEH, and currently based at CEH Monks Wood. BRC is jointly funded by CEH and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (www.jncc/gov.uk), the latter acting on behalf of the statutory conservation agencies in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. CEH and JNCC support BRC as an important component of the National Biodiversity Network. BRC seeks to help naturalists and research biologists to co-ordinate their efforts in studying the occurrence of plants and animals in Britain and Ireland, and to make the results of these studies available to others. For further information, visit www.ceh.ac.uk Cover photograph: Bryophyte-dominated vegetation by a late-lying snow patch at Garbh Uisge Beag, Ben Macdui, July 2007 (courtesy of Gordon Rothero). Published by Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Monks Wood, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, PE28 2LS. Copies can be ordered by writing to the above address until Spring 2008; thereafter consult www.ceh.ac.uk Contents Introduction . -

Devon Local Sites Manual V1.2 May 2009

The Devon Local Sites Manual Policies and Procedures for the Identification and Designation of Wildlife Sites Version 1.2 – May 2009 Devon Biodiversity Records Centre 27 Commercial Road Exeter EX2 4AE (01392) 274128 [email protected] Changes to the Devon Local Site Manual: Changes agreed by DBRC Steering Group 11/09/08 (v1.1): Section 1: Introduction • p5: Section on Local Wildlife Sites amended • p10: Deleted sites updated Section 3: Habitat Guidelines • p13: Section 3.1.2.1 (b) Non-ancient woodland amended Appendices: • p44: Appendix 3 Calcifugous grassland amended Changes agreed by DBRC Steering Group 08/05/09 (v1.2): Section 1: Introduction • p4: Section on proposed County Wildlife Sites (pCWS) amended Section 2: The Selection of County Wildlife Sites • p8: Section 2.5 – new list of evidence that can be used in the selection of CWS • p11: Section 2.11– section on notification of landowners updated Section 3: Habitat Guidelines • p15: Section 3.1.5 – parkland criteria now complete Appendices: • p41-56: Appendices 2 -7 - IHS categories added to all the NVC community appendices • p47: Appendix 3 - table for indicator species of neutral grasslands added • p57-65: Appendix 8 - vascular plant list updated, old status (e.g. DN1) reinstated, references added. i ii Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Non-statutory Wildlife Site Selection Procedure 3. Habitat Guidelines for County Wildlife Sites 3.1 Woodlands 3.1.1 Ancient Woodlands 3.1.2 Non-ancient Woodlands 3.1.3 Wet Woodlands 3.1.4 Scrub 3.1.5 Parkland, Wood Pasture and Veteran Trees 3.1.6 Traditional Orchards 3.2 Grasslands 3.3 Lowland Heath 3.4 Upland Habitats 3.5 Mires, bogs, fens and swamps 3.6 Standing Waters 3.7 Rivers 3.8 Coastal floodplains and grazing marsh 3.9 Coastal and marine 3.10 Non-montane rock habitats 3.11 Artificial habitats 3.12 Mosaic sites 4.