Wombats 5O Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

February 2018

February 2018 Welcome back to our regulars and a very warm welcome aboard to our new recruits. We are finding that some of our new recruits have some great stories to tell. Sincere thanks to our regular contributors, Gary Martinic, Chris Meuzelaar and Paul Rosenzweig for their continued support. You can read an article from Paul on 6 Wing activities in this edition. There are some great insights out there showing the work the AAFC Staff and Cadets are doing and it is not just the average home Squadron activities. Thanks also to our dedicated supporters of the Quiz. Without them we wouldn’t know if our magazine was getting out. We have discussed the continuation of the magazine. Is it worth continuing? We really don’t know if it is being read or if we have lost our way. We have sent out over 25 editions of the Magazine and we really need to know if it is worth the effort for a couple of people. We would welcome your comment, and/or some articles of interest. UPDATE ON AAFC ANNUAL HERITAGE WRITING COMPETITION As forecast in the November edition of the Air Cadets Alumni e-Mag, an annual Heritage Writing Competition has been organised and managed by your Alumni Committee. The competition is supported by CAF and was launched by the AAFC Commander on 18 November 2017. See the AAFC Commander’s video message here. In this inaugural year of the competition, entry is restricted to current AAFC staff and cadets and there are cash and other prizes to be won. -

Farewell Qantas

Farewell Qantas 747 Wednesday 22 July was a sad day for many aviation enthusiasts as Qantas’ last Boeing 747-438 ER, VH-OEJ, ‘Wunala’, departed Sydney for Los Angeles and eventually to the aircraft boneyard in Victorville on the edge of the Mojave Desert, to be placed into storage. The departure was done in style though with all the fanfare and flourish befitting the ‘Queen of the Skies’! After push back, the aircraft initially performed a ‘lap of honour’ at Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport, complete with the traditional water cannon salute, before departing on Runway 16R as QF7474. The departure was followed by some low level passes over the Sydney metropolitan area before VH-OEJ turned south to the Illawarra to fly over her older sibling, VH-OJA ‘City of Canberra’ at Shellharbour airport. The departure of VH-OEJ marks the end of almost 50 years of Qantas operating Boeing 747 ‘Jumbo jet’ aircraft. The first was a Boeing 747-238, entering service with Qantas in September 1971. A total of 65 747s were operated by Qantas during the period 1971 to 2020, including almost every variant offered by Boeing. Many Qantas staff, past and present, attended HARS on the day to wave farewell to VH-OEJ and catch up with old friends from their days of flying. As VH-OEJ passed over Shellharbour airport at 1,500 feet, Captain Sharelle Quinn saluted the first Qantas 747-438: “...from the last Qantas Boeing 747, farewell to HARS and farewell to OJA,” before setting course for Los Angeles. At least that’s what everyone thought until somebody noticed on a flight tracking app, the aircraft turning back towards Port Macquarie. -

Page | 1 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN AVIATION MUSEUM SIGNIFICANT AVIATION EVENTS a BRIEF HISTORY of the AUSTRALIAN SABRE This Article Is D

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN AVIATION MUSEUM SIGNIFICANT AVIATION EVENTS A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AUSTRALIAN SABRE This article is derived from a speech that Group Captain Robert (Bob) MacIntosh (Ret.) gave to the Civil Aviation Historical Society of South Australia on 13 June 2013. Bob kindly gave me permission to plagiarise his speech notes and he contributed the photographs. He has also confirmed that I have not inadvertently introduced any errors to my edited version - Mike Milln 24 June 2013 As early as 1949 the RAAF began planning a replacement jet fighter for the locally-built CAC (Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation) Mustang and de Havilland Vampire. A number of existing and proposed aircraft were considered but, in the event, Gloster Meteors were obtained in 1951 for service with No 77 Squadron in the Korean War. In May 1951, plans were finalised for CAC to build a locally-designed version of the North American F-86F Sabre swept-wing fighter. Due in part to the technical investigations initiated by CAC Manager L.J. Wackett, the RAAF FLT SGT Bob MacIntosh in an Avon Sabre decided to substitute 7,500Lb thrust Rolls-Royce Courtesy Bob MacIntosh Avon RA.7 turbojets for the 6,100lb thrust General Electric J-47s. This required major modifications including a larger nose-intake and positioning the Avon further aft; plus other improvements such as increased fuel capacity, a revised cockpit layout and replacement of the six 0.5 inch machine guns with two 30mm Aden cannons. This all resulted in CAC having to redesign 50% of the airframe and an aircraft, sometimes called the Avon-Sabre, that became the best of the many Sabre variants built around the world. -

The Joys and Dangers of an Aviation Pilot

Heritage Series The Joys and Dangers of an Aviation Pilot Leigh ‘Laddie’ Hindley Winner of the 2012 RAAF Heritage Award © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Cover Image: Laddie Hindley, Richmond, 1945 (Hindley family). Back Cover Image: Laddie placing the cross on Saint Mathew’s Anglican Church, Windsor, NSW, 1963 (Hindley family). National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Hindley, Leigh Oxley, author. Title: The Joys and Dangers of an Aviation Pilot / Leigh Oxley Hindley. Publisher: The Air Power Development Centre ISBN: 9781920800802 (paperback) Subjects: Air pilots--Australia--Biography. World War, 1939-1945--Aerial operations, Australian. Vietnam War, 1961-1975--Aerial operations, Australian. Other Authors/Contributors: Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre, issuing body. Dewey Number: 629.13092294 Air Power Development Centre Office of Air Force History Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre F3-G, Department of Defence Telephone: + 61 2 6128 7041 PO Box 7935 Facsimile: + 61 2 6128 7053 CANBERRA BC 2610 Email: [email protected] AUSTRALIA Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Editor’s Note The Joys and Dangers of an Aviation Pilot is a personal account of Leigh Oxley Hindley’s experiences as a RAAF and commercial pilot. -

Print This Page

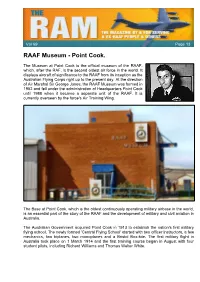

Vol 49 Page 3 Vol 69 Page 13 RAAF Museum - Point Cook. The Museum at Point Cook is the official museum of the RAAF, which, after the RAF, is the second oldest air force in the world. It displays aircraft of significance to the RAAF from its inception as the Australian Flying Corps right up to the present day. At the direction of Air Marshal Sir George Jones, the RAAF Museum was formed in 1952 and fell under the administration of Headquarters Point Cook until 1988 when it became a separate unit of the RAAF. It is currently overseen by the force's Air Training Wing. The Base at Point Cook, which is the oldest continuously operating military airbase in the world, is an essential part of the story of the RAAF and the development of military and civil aviation in Australia. The Australian Government acquired Point Cook in 1913 to establish the nation's first military flying school. The newly formed 'Central Flying School' started with two officer instructors, a few mechanics, two biplanes, two monoplanes and a Bristol Box-kite. The first military flight in Australia took place on 1 March 1914 and the first training course began in August with four student pilots, including Richard Williams and Thomas Walter White. RAAF Radschool Association Magazine. Vol 69. Page 13 During World War I the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was established at Point Cook as a new element of the army. Many of its pilots saw active duty overseas, in the Middle East and the Western Front. The first Australian airman to die in action was Lieutenant George Merz, one of the first pilot graduates from Point Cook, who was killed in Mesopotamia. -

Defence Self-Reliance and Plan ‘B’

1 Defence Self-Reliance and Plan ‘B’ Alan Stephens For 118 years, since Federation in 1901, the notion of “self-reliance” has been one of the two most troublesome topics within Australian defence thinking. The other has been “strategy”, and it is no coincidence that the two have been ineluctably linked. The central question has been this: what level of military preparedness is necessary to achieve credible self-reliance? What do we need to do to be capable of fighting and winning against a peer competitor by ourselves? Or, to reverse the question, to what extent can we compromise that necessary level of preparedness before we condemn ourselves to becoming defence mendicants – to becoming a nation reliant for our security on others, who may or may not turn up when our call for help goes out? Pressure points within this complex matrix of competing ideas and interests include leadership, politics, finance, geography, industry, innovation, tradition, opportunism, technology and population. My presentation will touch on each of those subjects, with special reference to aerospace capabilities. My paper’s title implies that we have a Plan A, which is indeed the case. Plan A is, of course, that chestnut of almost every conference on Australian defence, namely, our dependence on a great and powerful friend to come to our aid when the going gets tough. From Federation until World War II that meant the United Kingdom; since then, the United States. The strategy, if it can be called that, is simple. Australia pays premiums on its national security by supporting our senior allies in wars around the globe; in return, in times of dire threat, they will appear over the horizon and save us. -

Modern Combat Aircraft (1945 – 2010)

I MODERN COMBAT AIRCRAFT (1945 – 2010) Modern Combat Aircraft (1945-2010) is a brief overview of the most famous military aircraft developed by the end of World War II until now. Fixed-wing airplanes and helicopters are presented by the role fulfilled, by the nation of origin (manufacturer), and year of first flight. For each aircraft is available a photo, a brief introduction, and information about its development, design and operational life. The work is made using English Wikipedia, but also other Web sites. FIGHTER-MULTIROLE UNITED STATES UNITED STATES No. Aircraft 1° fly Pg. No. Aircraft 1° fly Pg. Lockheed General Dynamics 001 1944 3 011 1964 27 P-80 Shooting Star F-111 Aardvark Republic Grumman 002 1946 5 012 1970 29 F-84 Thunderjet F-14 Tomcat North American Northrop 003 1947 7 013 1972 33 F-86 Sabre F-5E/F Tiger II North American McDonnell Douglas 004 1953 9 014 1972 35 F-100 Super Sabre F-15 Eagle Convair General Dynamics 005 1953 11 015 1974 39 F-102 Delta Dagger F-16 Fighting Falcon Lockheed McDonnell Douglas 006 1954 13 016 1978 43 F-104 Starfighter F/A-18 Hornet Republic Boeing 007 1955 17 017 1995 45 F-105 Thunderchief F/A-18E/F Super Hornet Vought Lockheed Martin 008 1955 19 018 1997 47 F-8 Crusader F-22 Raptor Convair Lockheed Martin 009 1956 21 019 2006 51 F-106 Delta Dart F-35 Lightning II McDonnell Douglas 010 1958 23 F-4 Phantom II SOVIET UNION SOVIET UNION No. -

Model Expo 2016 - Competition Results

Model Expo 2016 - Competition Results Category Placings MEJA - Junior - Aircraft (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by Andrews Hobbies 1st Place Harry mccumiskey HELLCAT 2nd Place Xavier McArthur Friendship 3rd Place Savannah McArthur Hellcat MEJC - Junior - Civil Vehicles (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by DEKLS 1st Place Joseph Powzyk 63 Corvette Stingray coupe 2nd Place Harrison SchembrI 1969 Z/28 22 CAMARO 3rd Place Leo Scicluna 1959 Chevrolet El Camino "Grumpys Toyto Car" Commendation Lincon Sharp 49 Mercury police patrol car Commendation Lincon Sharp Porsche Cayman MEJE - Junior - Military AFVs, vehicles & equipment (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by HobbyLink Japan 1st Place Alex Frowen SAS Jeep 2nd Place Joseph Powzyk Rainbow Tank MEJM - Junior - Miscellaneous (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by Red Roo Models 1st Place Ashley Cropley ORC WARBOSS 2nd Place Ashley Cropley ORC BISMEK 3rd Place Joseph Powzyk Captain Phasma Commendation Marcus Cropley SCARABS Commendation Ashley Cropley BATTLEWAGON Commendation Ashley Cropley MARKANAUT Commendation Marcus Cropley IMPERIAL KNIGHT MEIE - Military AFVs, vehicles & equipment (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by Model World SA 1st Place John Haycroft Tiger 1 Ausf. E 2nd Place Evan Nott Sherman Firefly 3rd Place Evan Nott M113A1 MEIG - Sci-Fi, Movie & Fantasy (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by HobbyLink Japan 1st Place Christopher Kouvelis Ultra marine 2nd Place Christopher Kouvelis Cadian sniper 3rd Place Evan Nott Rainbow Dash MEIM - Miscellaneous (All scales) OPEN Sponsored by Model World SA 1st Place Fletcher Sheeran -

HPK048011 Canadair Sabre Mk 4 and Mk 5

P C4 L P D15 6 R P D16 L P D48 CAC SABRE Mk32 “AVON SABRE” P C5 R P D49 P C25 K 072074 P C26 1/72 Scale Model Construction Kit HISTORY 11 The CAC Avon Sabre was a unique aircraft in Australian military aviation history. It was the first all metal jet fighter to be constructed in this country. The decision to produce the North American Aviation (NAA) F-86 Sabre, fitted with the Rolls-Royce Avon turbo-jet engine and upgraded armament in the form of two ADEN cannons, saw CAC embark upon a major re-design program. Because the Avon engine was lighter, shorter and of greater diameter than the General Electric J34 engine which powered the NAA Sabre, CAC incorporated major structural changes in the Sabre fuselage, resulting in a total P C27 redesign of almost 40% of the fuselage. P C28 The Avon Sabre gave sports car like performance as well as packing quite a punch. ln service the aircraft proved to be versa- tile and although no trainer variant was produced in Australia pilot conversion proceeded with reasonable speed. As NAA produced modifications to the basic design these were incorporated in CAC built aircraft. The slatted wing was replaced Option: with the famous ‘six-three’ wing. Sidewinder missiles were fitted to the aircraft and even ground attack missions were incor- The CAC Sabre often flew with drop porated within the aircraft’s repertoire. ? tanks. The Sabre served operationally with 3, 75, 76, 77 & 79 Squadrons, and 2 OTU & 3 OCU between 1953-68. -

Überraschend Und Gut... Milano Malpensa X

Deutschland: 5,90 € Nr. 1/2017 Österreich: 6,50 € • Schweiz: 9,90 SFr Dezember 2016/Januar 2017 FS MAGAZIN MAGA ZIN FS Die Fachzeitschrift für Flugsimulation • Überraschend und gut... Milano Malpensa X • Ein Stück Luftfahrtgeschichte: One-Eleven 300/400/500 • Fliegerisch anspruchsvoll: Airport Buochs X • Startup-Szenerie:• Darf getreten Venice werden: Marco RUDDO Polo VST - Verlag für Simulation und Training GmbH • www.fsmagazin.de • 12. Jahrgang • Nr. 1/2017 Nr. • Jahrgang 12. • www.fsmagazin.de • GmbH Training und Simulation für Verlag - VST Simmarket_f_GER_2016_11 Linkliste zum FS MAGAZIN 1/2017 Irrtümer und Änderungen vorbehalten Linkliste zum kostenlosen Download www.fsmagazin.de/download/FSM1_2017Linkliste.pdf Plusartikel zum kostenlosen Download www.fsmagazin.de/download/FSM1_2017Plusartikel.pdf Aktuelles und Kurzmeldungen Links Stichwörter Automatic Terminal Information System http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_Terminal_Information_Service (ATIS) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_Terminal_Information_Service www2.bombardier.com/Used_Aircraft/en/Q_Dash_Overview.jsp Bombardier Dash 8 http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardier_Q_Series https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardier_Dash_8 www.drf-luftrettung.de/de/menschen/standorte/station-halle Christoph Sachen-Anhalt www.rth.info/stationen.db/station.php?id=70 https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christoph_Sachsen-Anhalt www.drf-luftrettung.de/de/menschen/standorte/station-halle Christoph Halle www.rth.info/stationen.db/station.php?id=60 https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christoph_Halle