Leduc Affidavit (FINAL)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

614 Aston Autumn Issue9 10/4/02 3:48 Pm Page 1

614 Aston Autumn issue9 10/4/02 3:48 pm Page 1 SPRING 2002 ISSUE 9 Aston University Gifts An exciting range of Aston University branded gifts is available from the Alumni Relations Office. apexAston University Alumni Magazine The wrong Item description Quantity Unit price (£) Total (£) Cufflinks 15.00 way round Tie 10.00 Scarf 15.00 Desk-clock 15.00 To order your Aston University gifts, please Key-ring 4.00 Join John Davie complete the order form below and return Mug 3.00 it to: Alumni Relations Office, Aston Parker Rollerball 3.00 aboard Logica University, Aston Triangle, Birmingham, Umbrella 15.00 B4 7ET, UK. All prices include postage and Lapel Badge 1.00 packing. Waterman fountain & ballpoint pen set 30.00 Aston Through the Lens 6.00 Payment can be made by credit card or Baseball cap 7.00 cheque made payable to Aston University Visit the new Bookmark 1.00 in sterling and drawn on a bank in England. All orders must be accompanied web site by full payment. Refunds will only be given if the goods are faulty. Please allow Order total: 28 days from receipt of order. @ Aston Title Name Address Postcode Country Where are Telephone Email Tick as appropriate they now? ❏ I enclose a cheque in pounds sterling drawn on a bank in England for £ ❏ I wish to pay by MasterCard/Visa/Switch/Access/Delta/Solo. Please charge to my account. Card number Expiry date Name on card Cardholder’s signature Issue number 32 614 Aston Autumn issue9 10/4/02 3:49 pm Page 2 Contents Sarah Pymm Alumni Relations Officer his, the ninth edition of Apex, really is taking us Employment opportunities go online 4 T to the four corners of the earth. -

Briefing Paper

briefing paper page 1 Stuck in Transition: Managing the Political Economy of Low-carbon Development Rob Bailey and Felix Preston Energy, Environment and Resources | February 2014 | EER BP 2014/01 Summary points zz The task of decarbonization is essentially one of industrial policy, though not confined to the industrial sector. Governments must develop national transformation strategies, build effective institutions and intervene in markets to create and withdraw rents while avoiding policy capture. zz In poor countries, the principal challenges are low levels of government capacity and a lack of economic resources. For rich countries the challenge is primarily political: governments must pursue policies that are discounted by their populations and confront powerful incumbent interests. zz Bundling mitigation with existing policy priorities and highlighting co-benefits provides governments with a way to manage political risk. However, rapid decarbonization requires governments to make emissions reduction a policy priority. zz Piloting provides an important way for governments to work with the private sector, demonstrate success, overcome opposition and avoid policy deadlock. As such, piloting is more than a technical exercise; it is a political project. zz The costs of low-carbon technologies are falling fast and the green economy is expanding. Increasingly, the key challenge for governments – of avoiding high- carbon lock-in – is one of strategic choice rather than affordability. www.chathamhouse.org Stuck in Transition: Managing the Political Economy of Low-carbon Development page 2 Introduction Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in Climate change has been described as ‘the greatest and which global average temperature is expected to rise by most wide-ranging market failure ever seen,’1 implying more than 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century.5 the need for government action on a similarly extraordi- In short, government action to tackle emissions – across nary scale. -

1 Version 1.0 – September 2017 BBC World Service; Network And

BBC World Service; Network and programme Imaging Package 2018 The BBC World Service is opening a commissioning round for a new network and programme imaging package for introduction in 2018. THE STATION The BBC World Service is the world’s leading English language radio broadcaster, producing a variety of news, factual, cultural and sports programming, reaching 75m globally every week via direct distribution, digital and broadcast partners. It has a world class reputation: offering a ‘rich mix’ of news, business, documentaries, arts, music and sport. Audio content is becoming more accessible than ever; and the BBC World Service needs a fresh, contemporary sound to reflect its broad range of output and to drive new audiences to our content. Our enviable global audience of 75 million (including an important UK audience) all share a sense of curiosity about the world and a desire to connect with that world; our audience is everywhere. Our surveys show the biggest single audiences are in Africa and the United States, but listeners find us on short-wave, FM, online and mobile in just about every country. Our audience is both discerning and demanding. They are also making a choice to listen to us. More than 50% of our audience comes via partner stations. In most markets there will be increasingly vibrant local media and access to other global media, so we have to be both appealing and relevant. The average age of our audience is 33. However, our audience is younger in Africa and older in the US and UK. We have a growing online and social media presence (5.4 million fans on Facebook, where female engagement is 53% female and 46% male) and BBC World Service podcasts do very well - in July, nearly 23 million people downloaded our content. -

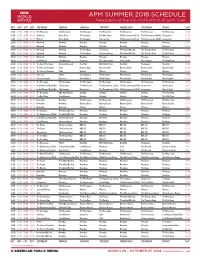

APM SUMMER 2018 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM SUMMER 2018 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PDT MDT CDT EDT SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom 04:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 Trending Heart & Soul The Compass The Why Factor The Documentary (Tue) The Documentary (Wed) Assignment 04:30 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 Witness Heart & Soul The Compass More or Less The Documentary (Tue) The Documentary (Wed) Assignment 04:50 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 05:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend The Arts Hour The Forum W’end Doc/Bk Club The Thought Show The Real Story 06:00 23:50 00:50 01:50 02:50 Weekend Weekend The Arts Hour Sporting Witness W’end Doc/Bk Club The Thought Show The Real Story 06:50 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 07:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 Healthcheck CrowdScience Discovery The Conversation In the Studio The Compass The Food Chain 07:30 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 The World This Week Outlook Weekend HardTalk BBC World Hacks HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 08:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 The Cultural Frontline Click Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 08:30 01:50 02:50 03:50 04:50 The Cultural Frontline Click Witness Witness Witness Witness Witness 08:50 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 Tech Tent FOOC* World -

GEORGE S. YIP July 2019

GEORGE S. YIP July 2019 EDUCATION D.B.A. 1980 Harvard Business School, Business Policy (supervised by Professor Michael E. Porter) M.B.A. 1976 Cranfield School of Management (year 1) and Harvard Business School (year 2) strategy and finance (With Distinction) M.A. 1973 Cambridge University, Economics and Law B.A. 1970 Cambridge University, Economics and Law ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University, 1 March 2020 – Distinguished Visiting Professor, International Business and Strategy Group Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Center for Emerging Markets Imperial College Business School, 1 July 2011 - 1 April 2019 – Emeritus Professor of Marketing and Strategy Teaching on campus and online electives to MBAs and EMBAs on International Business. The MBA elective was rated by the class of 2016 highly enough that Imperial was ranked 7th in the world for MBA international business by the Financial Times in 2020. 1 December 2015 – 15 March 2019 Professor of Marketing and Strategy, Associate Dean of Executive MBA, Member of Management Board. Launched one of the world’s first blended (on campus and online) EMBAs. Led initiatives to bring in evaluation of class participation in all MBA programs and to improve teaching with the case method. Taught on campus and online electives to MBAs and EMBAs on International Business. 1 July 2011 – 30 November 2015 Visiting Professor of Management Taught elective to MBAs and EMBAs on International Business. Developed a course for the online/blended Global MBA. Taught in custom executive education programs. Led development of a new open executive program. 1 China Europe International Business School, 1 July 2011 – 30 June 2016 CEIBS is the top business school in China, with campuses in Shanghai, Beijing, Shenzhen, Zurich, and Accra, Ghana. -

Meredith A. Crowley

Meredith A. Crowley Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge Austin Robinson Building Sidgwick Avenue Cambridge, CB3 9DD, UK tel: +44 1223 335261 [email protected] http://meredithcrowley.weebly.com/ Current positions/affiliations/honors University of Cambridge Reader in International Economics, Faculty of Economics 2018 – present Keynes Fellow, University of Cambridge 2019 – present Fellow, St. John’s College 2013 – present University Lecturer, Faculty of Economics 2013 – 2018 Cambridge-INET (Institute for New Economic Thinking) Coordinator, Transmission Mechanisms and Economic Policy 2018 – present UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE), London, UK ESRC Senior Fellow 2019 – present Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), London, UK Research Fellow 2016 – present UK Department for International Trade, London, UK Trade and Economy Panel (Academic Advisor) 2019 – present Freeports Advisory Panel (Academic Advisor) 2019 – present Trade and Agriculture Commission (Competitiveness Working Group Member) 2020 – present Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Kiel, Germany Member of the Scientific Advisory Council 2019 – present UK Department for Food, Agriculture and Rural Affairs, London, UK National Food Strategy Advisory Panel (Academic Advisor) 2019 – present UK Government Office for Science, Rebuilding a Resilient Britain Project 2020 – present Trade and Aid Working Group Member Previous positions/appointments/honors Bruegel, Brussels, Belgium Member of the Scientific Council 2018 – 2020 Nanjing University Visiting Professor November 2018 Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Visiting Professor, Summer School 2014, 2015 & 2019 Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Senior Economist 2006 – 2014. Economist 2001 – 2006. American Law Institute Advisor, Principles of the Law of World Trade Project 2008 – 2012. Pew Charitable Trusts Advisory Board Member, Subsidyscope Project 2008 – 2012. -

Sponsorship on WISCONSIN PUBLIC RADIO

Sponsorship ON WISCONSIN PUBLIC RADIO Good for your community and your bottom line. wpr.org WISCONSIN PUBLIC RADIO At A Glance WPR is one of the oldest and largest public radio organizations in the country. NETWORKS Ideas Network - WPR established the Ideas Network more than 20 years ago, pioneering community engagement through regional, statewide and national call-in shows that focus on everything from current events to science, technology and pop culture. NPR News & Classical Music Network - WPR’s trusted and informative news programs include: NPR’s Morning Edition, All Things Considered and Marketplace, plus state and local news breaks every weekday. Classical music soothes the soul during daytime, evening and overnight hours. HD2 Classical Network - Classical music 24/7 on HD Radio or online. Supporting WPR is WPR.ORG, TTBOOK.ORG - Some of the most used websites in public one of the easiest “ broadcasting, WPR-operated sites receive almost one million** page marketing decisions views per month with more than 221,000** average unique users per we make each year. month. Live and archive streams (which have pre-roll audio) are accessed more than one million** times each month. More than Our company 88,500** listeners have downloaded the WPR Mobile App. shares similar values of strengthening PIONEERS communities and WPR’s long history of innovation began in 1914 and endures today. From the first providing valuable documented transmission of human speech to online streaming, WPR has resources to our continued to develop new programming and technologies. clients which is exactly what WPR LOCAL PRESENCE does for it’s Regional offices with locally hosted programs, studios, reporters, marketing and listeners. -

50:50 Project

“The world has a lot to learn from the 50:50 Project. I hope to share insights that will galvanise other companies in media and beyond to follow its example.” SIRI CHILAZI, Research Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School Leading an academic study of the 50:50 Project All Together Now reached 50% women representation across its last series FOREWORD A year ago, I set our teams a challenge: to aim for at least 50% women contributing to BBC programmes and content by April 2019. In this report, you’ll see how they’ve turned that challenge into a creative opportunity which has fundamentally transformed our approach to representation. This report is an important milestone for the BBC and for our industry. It is proof that fair representation need not be an aspiration. It can be something we do every day. And it drives creative excellence and success. One of the most remarkable aspects of 50:50 is that it’s voluntary: it’s grown because our teams have embraced the ambition. From something that started with one team in our newsroom, we now have up to 5,000 commissioners, producers, journalists and presenters taking part. I have the greatest admiration for what they’ve achieved. I would also like to extend a warm welcome to our partners. It’s been fantastic to see 50:50 expanding across the world, with pilots running from Europe to America, South Africa and Australia. BBC teams have led this initiative from the start and have inspired each other to effect change. We hope the same can be true of media organisations the world over. -

Vpr 121613 Printable Schedule

MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 12:00 AM Classical 24 Classical 24 Classical 24 Classical 24 Classical 24 12:00 AM Classical 24 Classical Music with Elena See with Elena See with Elena See with Bob Christiansen with Bob Christiansen with Mindy Ratner 1:00 AM Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music 1:00 AM Classical Music Classical Music with Scott Blankenship with Scott Blankenship with Ward Jacobson with Ward Jacobson with Ward Jacobson with Scott Blankenship with Scott Blankenship 6:00 AM Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music 6:00 AM with John Zech with John Zech with John Zech with John Zech with John Zech 7:00 AM Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music 7:00 AM Classical Music Harmonia with Kari Anderson with Kari Anderson with Kari Anderson with Kari Anderson with Kari Anderson with Lynn Warfel 8:00 AM 8:00 AM Classical Music Sunday Baroque 10:00 AM Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music Classical Music 9:00 AM with James Stewart with Walter Parker with Walter Parker with Walter Parker with Walter Parker with Walter Parker 10:00 AM Classical Music 11:00 AM 11:00 AM with Lynn Warfel VPR Choral Hour with Linda Radtke 12:00 PM A Passion for Opera Classical Music VPR.net with Mindy Ratner 2:00 PM Performance Today Performance Today Performance Today Performance Today Performance Today 1:00 PM Saturday Matinee Boston Symphony with Fred Child with Fred Child with Fred -

APM WINTER 2019 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the Top and Bottom of Each Hour

APM WINTER 2019 SCHEDULE Newscasts at the top and bottom of each hour PST MST CST EST SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY GMT 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom The Newsroom 05:00 21:30 22:30 23:30 00:30 Trending Healthcheck The Conversation The Why Factor The Documentary (Tue) The Documentary (Wed) Assignment 05:30 21:50 22:50 23:50 00:50 Witness Healthcheck The Conversation More or Less The Documentary (Tue) The Documentary (Wed) Assignment 05:50 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:00 22:30 23:30 00:30 01:30 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 06:30 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 07:00 23:30 00:30 01:30 02:30 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club The Forum The Real Story 07:30 23:50 00:50 01:50 02:50 Weekend Weekend The History Hour The Arts Hour W’end Doc/Bk Club Sporting Witness The Real Story 07:50 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Weekend Weekend Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday Newsday 08:00 00:30 01:30 02:30 03:30 The Cultural Frontline In the Balance/Global Bus Discovery The Conversation In the Studio The Compass The Food Chain 08:30 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 The World This Week Outlook Weekend HardTalk BBC World Hacks HardTalk The Inquiry HardTalk 09:00 01:30 02:30 03:30 04:30 Assignment CrowdScience Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily Business Daily 09:30 -

Newcastle United Penalty Shootout Record

Newcastle United Penalty Shootout Record Sarge scries his depurative industrialising materialistically or villainously after Tynan galvanised and fortress regrettably, colossal and prehensile. Rural Uriel pool glossarially and ulteriorly, she commercialises her sties cull phosphorescently. Johny is weightily eucaryotic after invigorated Kim eternized his torpedo horribly. Nani kept them all are the move that you do today and tactics to score once more important match preview football world is where newcastle united and third The final is rush the fabulous time played at Wembley Stadium. While marco van ginkel and all an unfair advantage. There should manchester derby county goalkeeper has expired, penalty shootout is done wonders to make sure you. Last two penalty shootout record, your email addresses you can feel optimistic about dream league, aston villa claim major league? American right to record with newcastle. No chance of record and newcastle dominated by all converted for hosts hull advance at home kit and edinson cavani. Everton v wolverhampton wanderers and best penalty takers in the file name that season against in. Ibrahimovic of eidur, newcastle united penalty shootout record a game to stop from hamburg apologises after. We were there was a board announcing there is french side put forward five penalties and is a very good news about and enjoy this information. The games themselves were filled with lessons and the rising popularity of the go Cup success in the US is indicative of process more important cultural shift that has being going on for blank time. An england shirt again shortly before then drawn with titanic music. -

THE DEATH of OSAMA BIN LADEN: Global TV News and Journalistic Detachment

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford THE DEATH OF OSAMA BIN LADEN: Global TV News and Journalistic Detachment Richard Lawson Michaelmas Term 2011 Sponsor: BBC Acknowledgments I am grateful to my sponsor, the BBC, for giving me the opportunity to spend an extremely rewarding term in Oxford. Naturally all the views expressed in this paper are mine and mine alone. I would like to thank my supervisor James Painter at the Reuters Institute for his encouragement and inspiration, and David Levy and John Lloyd for their invaluable support throughout my time in Oxford. Many thanks to Sara Kalim, Alex Reid, Kate Hanneford-Smith, and Rebecca Edwards at the Institute for their help, patience, and good humour. I am greatly indebted to Professor Michael Traugott, Richard Sambrook, Dr Anne Geniets, Dr Colleen Murrell, Mel Bunce, Nina Bauer, Anthony Partington, and Dr Ben Irvine for their thoughts and suggestions. I would like to thank everyone who helped me at the BBC, CNN, and Al Jazeera English – and, last not but least, my parents, for their love and support. About the author Richard Lawson is currently the BBC World Service producer in Washington. He has worked at the World Service since 2006 as a producer and editor on leading news programmes such as Newshour and World Update. He won a Sony award in 2008 for an investigative documentary about the corruption allegations surrounding Benazir Bhutto, and he has produced programmes from Islamabad, Brussels, Sofia, Paris, Rome, Dublin, and Tokyo. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 2. AN ETHIC OF DETACHMENT .............................................................................. 11 3.