Principled Flexibility and Environmental Co-Management in the Mackenzie Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Outlook 2011 12 Final.Indd

Northwest Territories Economic Review 2011-12 Contents Introduction Minister’s Statement i Introduction 1 Key Economic Indicators 2 Investment 4 Employment 5 Economic Outlook Economic Outlook 7 Sustainability 11 Diavik Wind Farm 14 Economic Factors Introduction 16 Land 16 Population 18 Transportation Infrastructure 20 Business Climate 21 Business Distribution 22 Income Distribution Median Incomes 23 Income Distribution 24 Gender Incomes 26 Economic Sectors Non-Renewable Resources 29 Mackenzie Gas Project 34 Retail Trade 37 Wholesale Trade 38 Construction 39 Manufacturing 40 Tourism 41 Energy 44 Arts and Fine Crafts 49 Film 52 Fur and Fish Harvesting 55 Forestry 59 Agriculture 60 Conclusion 62 Honourable David Ramsay Minister of Industry, Tourism and Investment Government of the Northwest Territories The Northwest Territories is embarking on an era of opportunity and growth. Global economies are changing, new markets are growing, and international focus is shifting north – and we are poised to take full advantage of this incredible opportunity. Our vast natural resource base continues to provide the backbone to our territorial economy and provide opportunities to our residents. The NWT exports approximately $3 billion in diamonds and oil annually. However, signifi cant potential remains. Last year industry bid over $500 million in the Sahtu Region for land parcels that will be explored for oil potential. The rugged, pristine and isolated nature of the Northwest Territories is also a perfect fi t for the large and growing international tourism market – tourism contributes $100 million annually to our economy, and, like our resource industry, it is on the brink of tremendous growth. Our smaller industries are also capitalizing on the unique Northern setting. -

2018 Yellowknife Geoscience Forum Abstract and Summary Volume

2018 Abstract and Summary Volume Cover photograph Carcajou River, NWT; Viktor Terlaky, Senior Petroleum Geologist at the Northwest Territories Geological Survey The picture was taken following a rainstorm along Carcajou River, NWT, which resulted in a spectacular rainbow across the river valley. In the background are outcrops of the Late Devonian Imperial Formation, interpreted to be submarine turbidite deposits. The light bands are sandstone bodies intercalated with the darker shale intervals, representing periodic activity in sedimentation. Compiled by D. Irwin, S.D. Gervais, and V. Terlaky Recommended Citation: Irwin, D., Gervais, S.D., and Terlaky, V. (compilers), 2018. 46th Annual Yellowknife Geoscience Forum Abstracts; Northwest Territories Geological Survey, Yellowknife, NT. YKGSF Abstracts Volume 2018. - TECHNICAL PROGRAM - 2018 YELLOWKNIFE GEOSCIENCE FORUM ABSTRACTS AND SUMMARIES I Contents ordered by first author (presenting author in bold) Abstracts – Oral Presentations IBAS – to Regulate or Not: What is the Rest of Canada Doing? Abouchar, J. .......................................................................................................................... 1 Seabridge Discovers New Gold Zones at Courageous Lake Adam, M.A. ........................................................................................................................... 1 Gold Mineralisation at the Fat Deposit, Courageous Lake, Northwest Territories Adam, M.A. .......................................................................................................................... -

2018 Socio-Economic Agreement Report for Diamond Mines Operating in the Northwest Territories

TD 432-18(3) TABLED ON MAY 28, 2019 2018 Socio-Economic Agreement Report For diamond mines operating in the Northwest Territories Rapport de 2018 sur les accords socioéconomiques Mines de diamants des Territoires du Nord-Ouest Le present document contient la traduction française du résumé et du message du ministre If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ıś Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı.́ South Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı ́dé dúle. North Slavey Jii gwandak izhii ginjìk vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jì’, diits’àt ginohkhìi. Gwich’in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Indigenous Languages Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 II Contents MINISTER’S MESSAGE ......................................................................................................................................................IV MESSAGE DU MINISTRE ....................................................................................................................................................V -

Socio-Economic Agreement Report Rapport Sur Les Accords

2019 1 2019 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AGREEMENT REPORT SOCIO-ECONOMIC AGREEMENT REPORT For mines operating in the Northwest Territories RAPPORT SUR LES ACCORDS SOCIOÉCONOMIQUES Mines de diamants des Territoires du Nord-Ouest Le present document contient la traduction française du résumé et du message du ministre If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ıś Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı.́ South Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı ́dé dúle. North Slavey Jii gwandak izhii ginjìk vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jì’, diits’àt ginohkhìi. Gwich’in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 billbradenphoto Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 6 ECONOMIC OVERVIEW AND CURRENT NWT ECONOMY ....................................................................................................11 -

Annual Report 2015-2016

Table of Contents 3 Mission Statement 4 Dene Law 5 Message from the Chiefs 6 Message from the Chief Executive Officer 7 Yellowknives Dene First Nation Councilors – Current 8 Yellowknives Dene First Nation Councillors – 2011 – 2015 9 Department Reports: Wellness Division 10 Land & Environment 23 Aboriginal Head Start 30 YKDFN Housing Division 32 Administration - Human Resources 35 - YKDFN Organizational Chart 38 - Finance – IBA Funds 2014/2015 39 Det’on Cho Corporation 40 Acknowledgement 43 Mission Statement FIRST NATION MISSION To assert our Weledeh Dene Rights, as long as the sun rises, the rivers flow, and the grass grows FIRST NATION VISION Our vision is to be a Healthy and Sovereign Weledeh Dene Nation with Excellent Governance VALUE STATEMENTS We the YKDFN Chiefs and Council are guided by the following values: Weledeh Culture – we practice and promote our traditions, culture, language and spirituality Integrity – we are caring, respectful and honorable to all people Well-being – we live a healthy, balanced life that relies on nature Accountability – we are accountable and transparent to our people First Nation Summary (can be used as background information for proposals) The Yellowknives Dene First Nation (YKDFN) is part of the Akaitcho Territory Government. It is one of five main Dene groups that live in the NWT and is governed by a Chief and Council which has offices in Dettah and Ndilo. Overall, the YKDFN Chiefs and Council affirm our sacred obligation to serve our people and our commitment to live balanced contemporary lifestyles with culture and traditions important to our community, to speak our traditional language, and protect our natural resources and treaty rights. -

Hansard for October 31, 2016

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2nd Session Day 39 18th Assembly HANSARD Monday, October 31, 2016 Pages 1271 – 1294 The Honourable Jackson Lafferty, Speaker Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories Members of the Legislative Assembly Speaker Hon. Jackson Lafferty (Monfwi) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Hon. Glen Abernethy Hon. Bob McLeod Mr. Kevin O’Reilly (Great Slave) (Yellowknife South) (Frame Lake) Government House Leader Premier Minister of Health and Social Services Minister of Executive Minister Responsible for the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Hon. Wally Schumann Workers’ Safety and Compensation Intergovernmental Relations (Hay River South) Commission Minister of Industry, Tourism and Minister Responsible for Seniors Hon. Robert McLeod Investment Minister Responsible for Persons with Minister of Public Works and Services Disabilities (Inuvik Twin Lakes) Minister of Transportation Minister Responsible for the Public Deputy Premier Utilities Board Minister of Finance Minister of Environment and Natural Hon. Louis Sebert Resources (Thebacha) Mr. Tom Beaulieu Minister of Human Resources Minister of Justice (Tu Nedhe-Wiilideh) Lead Responsibility for Infrastructure Minister of Lands Minister Responsible for the Northwest Territories Power Corporation Mr. Frederick Blake Mr. Daniel McNeely Minister Responsible for Public (Mackenzie Delta) (Sahtu) Engagement and Transparency Hon. Caroline Cochrane Hon. Alfred Moses Mr. R.J. Simpson (Range Lake) (Inuvik Boot Lake) (Hay River North) Minister of Municipal and Community Minister of Education, Culture and Affairs Employment Minister Responsible for Northwest Minister Responsible for Youth Mr. Kieron Testart Territories Housing Corporation (Kam Lake) Minister Responsible for the Status of Mr. Michael Nadli Women (Deh Cho) Mr. Shane Thompson Lead Responsibility for Addressing (Nahendeh) Homelessness Mr. Herbert Nakimayak Ms. Julie Green (Nunakput) Mr. -

Preliminary Screening Report Form

Preliminary Screening Report Form Preliminary screener: MVLWB EIRB Reference / File Reference number: MV2005C0032, MV2005L2-0015 number: TITLE: Gahcho Kué Mine, Kennady Lake, NT ORGANIZATION: De Beers Canada Inc. MEETING DATE: June 7, 2017 Type of Development: New (CHECK ALL THAT APPLY) Amend, EIRB Ref. # Requires permit, licence, or authorization Does not require permit, licence, or authorization Project Summary Both Land Use Permit MV2005C0032 and Water Licence MV2005L2-0015 were referred to Environmental Assessment on December 22, 2005. The Mackenzie Valley Environmental Impact Review Board (MVEIRB) ordered an Environmental Impact Review (EIR) on June 12, 2006. MVEIRB released its Report of EIR and Reasons for Decision on July 19, 2013 and the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada approved the EIR on October 22, 2013. An Updated Project Description was submitted to the Mackenzie Valley Land and Water Board on November 28, 2013. Project components that have changed since the EIR, and have yet to be screened, including the following: • Pit depths have increased (Hearne Pit from 205m to 252m, 5034 Pit from 300m to 310m and Tuzo Pit from 300m to 360m); • Placement of Mine Rock into the Mined-out Hearne Pit; and • Height of the West Mine Rock Pile has increased from 94m to 100m. Project components that have changed since the EIR, but were discussed in either the Updated Project Description or submitted as updated information during the Mackenzie Valley Land and Water Board Regulatory Process, include the following: • 1 – 18 ML diesel fuel tank (total of 3 – 18 ML diesel tanks onsite) • 2 – 100,000 L diesel fuel tanks • 1 – 35,000 L diesel fuel tank • 20,000 L aviation fuel • 18 – 10,000 L tanks of various other hydrocarbons • 10 – 60,000 L tanks of various other hydrocarbons • 1,185,000 L (assorted drums and 1cu. -

Socio-Economic Agreement Report Rapport Sur Les

2019 TD 218-19(2) TABLED ON NOVEMBER1 3, 2020 2019 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AGREEMENT REPORT SOCIO-ECONOMIC AGREEMENT REPORT For mines operating in the Northwest Territories RAPPORT SUR LES ACCORDS SOCIOÉCONOMIQUES Mines de diamants des Territoires du Nord-Ouest Le present document contient la traduction française du résumé et du message du ministre If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations dans une autre langue officielle, contactez-nous. French Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Cree Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ıś Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı.́ South Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı ́dé dúle. North Slavey Jii gwandak izhii ginjìk vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jì’, diits’àt ginohkhìi. Gwich’in Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. Inuvialuktun ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Inuinnaqtun Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat: 867-767-9346 ext. 71037 Francophone Affairs Secretariat: 867-767-9343 billbradenphoto Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 6 ECONOMIC OVERVIEW AND -

The Ni Hadi Xa Agreement

NIHADIXA AGREEMENT THIS AGREEMENT made in the Northwest Territories, as ofthe day of , 2014. Between De Beers^Canada Inc. ("De Beers") and Deninu Kue First Nation Lutsel K'e Dene First Nation North Slave Metis AHianee Northwest Territory M^tis Nation Tl|ch9 Government (eolleetiveiy "Indigenous Parties") WHEREAS: A. De Beers proposes to establish a mine and related faeilities to be loeated on and adjacent to Kennady Lake, Northwest Territories for the production of rough diamonds known as the Gahcho Kue Diamond Mine; B. Each Indigenous Party has expressed concerns that the Gahcho Kue Diamond Mine will adversely affect their rights and will have an effect on their traditional lands, their relationship to the land, waterand resources, theh*^ social, cultural, ecorromic and spiritual values, their way oflife and the environment; C. This Agreement is intended to provide mechanisms to address the concerns of the Indigenous Parties to this Agreement about the effects of the Gahcho Kue Diamond Mine on the lands and the environment, sucb that those lands and the environment is protected for all peoples; D. De Beers recognizes and agrees to respect the rights of the Indigenous Parties while engaged in and planning its activities; E. De Beers recognizes and respects that Dene and Metis laws will inform the development of a long-term relationship with the Indigenous Parties to this Agreement; F. The Indigenous Parties and De Beers jointly proposed the N( Hadi Xa initiative before the Review Board; G. The Parties wish to ensure that the impacts ofthe Gahcho Kue Diamond Mine on the rights of the Indigenous Parties, their traditional lands, their relationship to the land, water and resources, their social, cultural, economic and spiritual values, their way of life and the environment are avoided or minimized; H. -

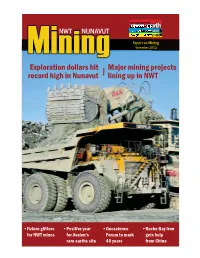

Miningi Mining Novembernovember 220120 Exploration Dollars Hit Major Mining Projects Record High in Nunavut Lining up in NWT

NWT NUNAVUT ReportReport on MiningMi Mining NovemberNovember 220120 Exploration dollars hit Major mining projects record high in Nunavut lining up in NWT •Future glitters • Positive year •Geoscience •Roche Bay Iron for NWT mines for Avalon’s Forum to mark gets help rare earths site 40 years from China A2 NEWS/NORTH NWT, November 2012 NWT/ NUNAVUT MINING `rNs/OsCh8i3j5 tu1Z5 Wdt1Q5 tu1Z5 W?9Oxt5ti3j5 tu1Z5 Click here NWT/ NUNAVUT MINING NEWS/NORTH NWT, November 2012 A3 photo courtesy of De Beers Canada An aerial look at De Beers Canada's Snap Lake mine, 220 km northeast of Yellowknife. Snap Lake has produced 881,000 carats since its opening in 2008. The company has spent $1.8 billion on capital and operating expenses. Future glitters for NWT mines Positive feasibility studies for several exploration projects by NNSL staff Northern News Services fact file NWT The NWT's three diamond mines may Mine Owner Commodity Basic facts Latest developments have some company in the coming years as Ekati Mine BHP Billiton, Diamonds Canada’s first and largest diamond mine, 310 2011 Year in Review report released. BHP Billiton is conducting other mineral and base and precious metal Chuck Fipke and km. NE of Yellowknife. Open pit and underground. review of diamonds business and potential sale. deposits come into production. Stu Blusson Mine life to 2019. Workforce approximately 1,500. Fortune Minerals' NICO cobalt, gold, Diavik Mine Rio Tinto and Diamonds Canada’s largest diamond producer, 300 km NE One million tonne underground production reached in May. Mine bismuth and copper project 50 km northeast Harry Winston of Yellowknife. -

Budget Address 2019 - 2020 NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

Budget Address 2019 - 2020 NORTHWEST TERRITORIES The Honourable Robert C. McLeod Minister of Finance Third Session of the Eighteenth Legislative Assembly February 6, 2019 If you would like this information in another official language, call us. English Si vous voulez ces informations en français, contactez-nous. French Cree Kīspin ki nitawihtīn ē nīhīyawihk ōma ācimōwin, tipwāsinān. Tłı̨chǫ yatı k’ę̀ę̀. Dı wegodı newǫ dè, gots’o gonede. Tłı̨chǫ Ɂerıhtł’ı́s Dëne Sųłıné yatı t’a huts’elkër xa beyáyatı theɂą ɂat’e, nuwe ts’ën yółtı. Chipewyan South Slavey Edı gondı dehgáh got’ı̨e zhatıé k’ę́ę́ edatł’éh enahddhę nıde naxets’ę́ edahłı́. North Slavey K’áhshó got’ı̨ne xǝdǝ k’é hederı ɂedı̨htl’é yerınıwę nı́dé dúle. Jii gwandak izhii ginjı̀k vat’atr’ijąhch’uu zhit yinohthan jı̀’, diits’àt ginohkhı̀i. Gwich’in Inuvialuktun Uvanittuaq ilitchurisukupku Inuvialuktun, ququaqluta. ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᑎᑎᕐᒃᑲᐃᑦ ᐱᔪᒪᒍᕕᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᓕᕐᒃᓯᒪᓗᑎᒃ, ᐅᕙᑦᑎᓐᓄᑦ ᐅᖄᓚᔪᓐᓇᖅᑐᑎᑦ. Inuktitut Inuinnaqtun Hapkua titiqqat pijumagupkit Inuinnaqtun, uvaptinnut hivajarlutit. Fiscal Policy: (867) 767-9158 Department of Finance Introduction - for the Government of the territoryMr. Speaker, to achieve,I rise today as setto presentout in the 2019very 20first Budget sentence of the 18th Legislative Northwest Territories. This Budget continues to invest in our peoplemmunities and andour Assembly mandate, our vision of a territory where all our people, co regions share in the benefits of a healthy, just,th sustainable and prosperous society. e mandate In presenting the final budget of the 18 Legislative Assembly, I want to thank Members for their collective efforts over the last four years to address th priorities within a less than ideal fiscal situation. -

Northern Mining News

Northern Mining News Volume 6, No. 7 July 2013 In this issue: Gahcho Kue diamond mine Panel recommends mine for permitting................................2 Board recommends Prairie Creek Water License for Approval..........................................3 NICO mine and mill receives government approval to proceed to licensing .....................4 Nechalacho Rare Earth Element project approval recommended.....................................6 Minister Approves 12‐year Water License for Mary River Iron Mine ................................7 Seabridge cameras capture wildlife painlessly...................................................................8 Gahcho Kue JV signs IBA with North Slave Metis ...............................................................9 New! 2012 Snap Lake Mine Socio‐Economic Report Released ..........................................9 Case Study on Diavik Wind Project...................................................................................10 Getting to ‘Yes’ – Strong messaging from former Indian Affairs Minister .......................10 Two Chamber mining members named in Best 50 Corporate Citizens in Canada...........11 CanNor signs MOU to work with NWT Government........................................................11 Lutsel K’e Youth Make Friends with Science ....................................................................13 De Beers Hay River Charity Golf Classic Sets New Fundraising Record ............................13 New Maps: Important Wildlife Areas in the Western Northwest Territories