The Real Quantum Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rutherford's Nuclear World: the Story of the Discovery of the Nuc

Rutherford's Nuclear World: The Story of the Discovery of the Nuc... http://www.aip.org/history/exhibits/rutherford/sections/atop-physic... HOME SECTIONS CREDITS EXHIBIT HALL ABOUT US rutherford's explore the atom learn more more history of learn about aip's nuclear world with rutherford about this site physics exhibits history programs Atop the Physics Wave ShareShareShareShareShareMore 9 RUTHERFORD BACK IN CAMBRIDGE, 1919–1937 Sections ← Prev 1 2 3 4 5 Next → In 1962, John Cockcroft (1897–1967) reflected back on the “Miraculous Year” ( Annus mirabilis ) of 1932 in the Cavendish Laboratory: “One month it was the neutron, another month the transmutation of the light elements; in another the creation of radiation of matter in the form of pairs of positive and negative electrons was made visible to us by Professor Blackett's cloud chamber, with its tracks curled some to the left and some to the right by powerful magnetic fields.” Rutherford reigned over the Cavendish Lab from 1919 until his death in 1937. The Cavendish Lab in the 1920s and 30s is often cited as the beginning of modern “big science.” Dozens of researchers worked in teams on interrelated problems. Yet much of the work there used simple, inexpensive devices — the sort of thing Rutherford is famous for. And the lab had many competitors: in Paris, Berlin, and even in the U.S. Rutherford became Cavendish Professor and director of the Cavendish Laboratory in 1919, following the It is tempting to simplify a complicated story. Rutherford directed the Cavendish Lab footsteps of J.J. Thomson. Rutherford died in 1937, having led a first wave of discovery of the atom. -

Physics of the Atom

Physics of the Atom Ernest The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1908 Rutherford "for his investigations into the disintegration of the elements, and the chemistry of radioactive substances" Niels Bohr The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922 "for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and of the radiation emanating from them" W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Early models of the atom atoms : electrically neutral they can become charged positive and negative charges are around and some can be removed. popular atomic model “plum-pudding” model: W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Rutherford scattering Rutherford did an experiment that showed that the positively charged nucleus must be extremely small compared to the rest of the atom. Result from Rutherford scattering 2 dσ ⎛ 1 Zze2 ⎞ 1 = ⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟ 4 dΩ ⎝ 4πε0 4K ⎠ sin ()θ / 2 Applet for doing the experiment: http://www.physics.upenn.edu/courses/gladney/phys351/classes/Scattering/Rutherford_Scattering.html W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Rutherford scattering the smallness of the nucleus the radius of the nucleus is 1/10,000 that of the atom. the atom is mostly empty space Rutherford’s atomic model W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Atomic Spectra: Key to the Structure of the Atom A very thin gas heated in a discharge tube emits light only at characteristic frequencies. W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Atomic Spectra: Key to the Structure of the Atom Line spectra: absorption and emission W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 The Balmer series in atomic hydrogen The wavelengths of electrons emitted from hydrogen have a regular pattern: Johann Jakob Balmer W. Ubachs – Lectures MNW-1 Lyman, Paschen and Rydberg series the Lyman series: the Paschen series: W. -

Bohr's Theory and Spectra of Hydrogen And

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Subject Chemistry Paper No and Title 8 and Physical Spectroscopy Module No and Title 7 and Bohr’s theory and spectra of hydrogen and hydrogen- like ions. Module Tag CHE_P8_M7 CHEMISTRY PAPER No. : 8 (PHYSICAL SPECTROSCOPY) MODULE No. : 7 (BOHR’S THEORY AND SPECTRA OF HYDROGEN AND HYDROGEN-LIKE IONS) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes 2. What is a Spectrum? 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Atomic Spectra 2.3 Hydrogen Spectrum 2.4 Balmer Series 2.5 The Rydberg Formula 3. Bohr’s Theory 3.1 Bohr Model 3.2 Line Spectra 3.3 Multi-electron Atoms 4. Summary CHEMISTRY PAPER No. : 8 (PHYSICAL SPECTROSCOPY) MODULE No. : 7 (BOHR’S THEORY AND SPECTRA OF HYDROGEN AND HYDROGEN-LIKE IONS) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you should be able to grasp the important ideas of Bohr’s Theory of the structure of atomic hydrogen. We will first review the experimental observations of the atomic spectrum of hydrogen, which led to the birth of quantum mechanics. 2. What is a Spectrum? 2.1 Introduction In spectroscopy, we are interested in the absorption and emission of radiation by matter and its consequences. A spectrum is the distribution of photon energies coming from a light source: • How many photons of each energy are emitted by the light source? Spectra are observed by passing light through a spectrograph: • Breaks the light into its component wavelengths and spreads them apart (dispersion). • Uses either prisms or diffraction gratings. The absorption and emission of photons are governed by the Bohr condition ΔE = hν. -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

A History of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Cosmology - Malcolm Longair

ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS - A History of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Cosmology - Malcolm Longair A HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY, ASTROPHYSICS AND COSMOLOGY Malcolm Longair Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, JJ Thomson Avenue, Cambridge CB3 0HE Keywords: History, Astronomy, Astrophysics, Cosmology, Telescopes, Astronomical Technology, Electromagnetic Spectrum, Ancient Astronomy, Copernican Revolution, Stars and Stellar Evolution, Interstellar Medium, Galaxies, Clusters of Galaxies, Large- scale Structure of the Universe, Active Galaxies, General Relativity, Black Holes, Classical Cosmology, Cosmological Models, Cosmological Evolution, Origin of Galaxies, Very Early Universe Contents 1. Introduction 2. Prehistoric, Ancient and Mediaeval Astronomy up to the Time of Copernicus 3. The Copernican, Galilean and Newtonian Revolutions 4. From Astronomy to Astrophysics – the Development of Astronomical Techniques in the 19th Century 5. The Classification of the Stars – the Harvard Spectral Sequence 6. Stellar Structure and Evolution to 1939 7. The Galaxy and the Nature of the Spiral Nebulae 8. The Origins of Astrophysical Cosmology – Einstein, Friedman, Hubble, Lemaître, Eddington 9. The Opening Up of the Electromagnetic Spectrum and the New Astronomies 10. Stellar Evolution after 1945 11. The Interstellar Medium 12. Galaxies, Clusters Of Galaxies and the Large Scale Structure of the Universe 13. Active Galaxies, General Relativity and Black Holes 14. Classical Cosmology since 1945 15. The Evolution of Galaxies and Active Galaxies with Cosmic Epoch 16. The Origin of Galaxies and the Large-Scale Structure of The Universe 17. The VeryUNESCO Early Universe – EOLSS Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical SketchSAMPLE CHAPTERS Summary This chapter describes the history of the development of astronomy, astrophysics and cosmology from the earliest times to the first decade of the 21st century. -

Memorial Tributes: Volume 15

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/13160 SHARE Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 DETAILS 444 pages | 6 x 9 | HARDBACK ISBN 978-0-309-21306-6 | DOI 10.17226/13160 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK National Academy of Engineering FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 Memorial Tributes NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Memorial Tributes Volume 15 THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. 2011 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-21306-6 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-21306-1 Additional copies of this publication are available from: The National Academies Press 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Lockbox 285 Washington, D.C. 20055 800–624–6242 or 202–334–3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area) http://www.nap.edu Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

Physiker-Entdeckungen Und Erdzeiten Hans Ulrich Stalder 31.1.2019

Physiker-Entdeckungen und Erdzeiten Hans Ulrich Stalder 31.1.2019 Haftungsausschluss / Disclaimer / Hyperlinks Für fehlerhafte Angaben und deren Folgen kann weder eine juristische Verantwortung noch irgendeine Haftung übernommen werden. Änderungen vorbehalten. Ich distanziere mich hiermit ausdrücklich von allen Inhalten aller verlinkten Seiten und mache mir diese Inhalte nicht zu eigen. Erdzeiten Erdzeit beginnt vor x-Millionen Jahren Quartär 2,588 Neogen 23,03 (erste Menschen vor zirka 4 Millionen Jahren) Paläogen 66 Kreide 145 (Dinosaurier) Jura 201,3 Trias 252,2 Perm 298,9 Karbon 358,9 Devon 419,2 Silur 443,4 Ordovizium 485,4 Kambrium 541 Ediacarium 635 Cryogenium 850 Tonium 1000 Stenium 1200 Ectasium 1400 Calymmium 1600 Statherium 1800 Orosirium 2050 Rhyacium 2300 Siderium 2500 Physiker Entdeckungen Jahr 0800 v. Chr.: Den Babyloniern sind Sonnenfinsterniszyklen mit der Sarosperiode (rund 18 Jahre) bekannt. Jahr 0580 v. Chr.: Die Erde wird nach einer Theorie von Anaximander als Kugel beschrieben. Jahr 0550 v. Chr.: Die Entdeckung von ganzzahligen Frequenzverhältnissen bei konsonanten Klängen (Pythagoras in der Schmiede) führt zur ersten überlieferten und zutreffenden quantitativen Beschreibung eines physikalischen Sachverhalts. © Hans Ulrich Stalder, Switzerland Jahr 0500 v. Chr.: Demokrit postuliert, dass die Natur aus Atomen zusammengesetzt sei. Jahr 0450 v. Chr.: Vier-Elemente-Lehre von Empedokles. Jahr 0300 v. Chr.: Euklid begründet anhand der Reflexion die geometrische Optik. Jahr 0265 v. Chr.: Zum ersten Mal wird die Theorie des Heliozentrischen Weltbildes mit geometrischen Berechnungen von Aristarchos von Samos belegt. Jahr 0250 v. Chr.: Archimedes entdeckt das Hebelgesetz und die statische Auftriebskraft in Flüssigkeiten, Archimedisches Prinzip. Jahr 0240 v. Chr.: Eratosthenes bestimmt den Erdumfang mit einer Gradmessung zwischen Alexandria und Syene. -

Physics 30 Lesson 31 the Bohr Model of the Atom I

Physics 30 Lesson 31 The Bohr Model of the Atom I. Planetary models of the atom After Rutherford’s gold foil scattering experiment, all models of the atom featured a nuclear model with electrons moving around a tiny, massive nucleus. A simple way to visualise the nuclear model was as planets orbiting a central Sun. As the Sun of our solar system attracted the planets, the positive nucleus of the atom would attract the negative electrons. While the Sun and planets involve gravitation, the nucleus and electrons involve electrostatic forces. Planet Nucleus Sun electron Gravitational Attraction Planetary Model of Atom The nuclear atom was a nice combination of gravitational ideas and sub atomic particles, but it had several major flaws: 1. Did all of the electrons travel in the same orbit? Why did they not bump into one another? What was the electron structure? 2. From the known bonding characteristics of different chemical compounds, how are the electrons involved in the bonding process? 3. Why do the positive protons stay together in the nucleus? Their strong mutual repulsion should tear the nucleus apart. 4. The final, and most important flaw, concerned the nature of accelerating charges. James Maxwell had shown that accelerating electric charges radiate EM radiation (Lesson 24). If the electrons were in circular orbits, they would continually experience a centripetal acceleration and should continually radiate energy in the form of electromagnetic waves. Further, since their kinetic energy is being converted into radiant energy, the electrons should spiral into the nucleus. From observation, we know that atoms have stable structures for long periods of time and they do not radiate energy on their own. -

Quantum Theory

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Arianna Borrelli Quantum Theory. A Media-Archaeological Perspective 2017 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2243 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Borrelli, Arianna: Quantum Theory. A Media-Archaeological Perspective. In: Anne Dippel, Martin Warnke (Hg.): Interferences and Events. On Epistemic Shifts in Physics through Computer Simulations. Lüneburg: meson press 2017, S. 95–121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2243. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 Attribution - Share Alike 4.0 License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 [6] Quantum Theory: A Media-Archaeological Perspective Arianna Borrelli Introduction: Computer Simulations as a Complement to Quantum Theory? In this paper I will provide some historical perspectives on the question at the core of this workshop, namely the many ways in which computer simulations may be contributing to reshape science in general and quantum physics in particular. More specifically, I would like to focus on the issue of whether computer simulations may be regarded as offering an alternative, or perhaps a complementary, version of quantum theory. I will not be looking at the way in which computer simulations are used in quantum physics today, since this task has been outstandingly fulfilled by other contributions to this workshop. Instead, I will present a few episodes from the history of quantum theory in such a way as to make it plausible that simulations might indeed provide the next phase of historical development. -

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective

Wolfgang Pauli 1900 to 1930: His Early Physics in Jungian Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota by John Richard Gustafson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advisor: Roger H. Stuewer Minneapolis, Minnesota July 2004 i © John Richard Gustafson 2004 ii To my father and mother Rudy and Aune Gustafson iii Abstract Wolfgang Pauli's philosophy and physics were intertwined. His philosophy was a variety of Platonism, in which Pauli’s affiliation with Carl Jung formed an integral part, but Pauli’s philosophical explorations in physics appeared before he met Jung. Jung validated Pauli’s psycho-philosophical perspective. Thus, the roots of Pauli’s physics and philosophy are important in the history of modern physics. In his early physics, Pauli attempted to ground his theoretical physics in positivism. He then began instead to trust his intuitive visualizations of entities that formed an underlying reality to the sensible physical world. These visualizations included holistic kernels of mathematical-physical entities that later became for him synonymous with Jung’s mandalas. I have connected Pauli’s visualization patterns in physics during the period 1900 to 1930 to the psychological philosophy of Jung and displayed some examples of Pauli’s creativity in the development of quantum mechanics. By looking at Pauli's early physics and philosophy, we gain insight into Pauli’s contributions to quantum mechanics. His exclusion principle, his influence on Werner Heisenberg in the formulation of matrix mechanics, his emphasis on firm logical and empirical foundations, his creativity in formulating electron spinors, his neutrino hypothesis, and his dialogues with other quantum physicists, all point to Pauli being the dominant genius in the development of quantum theory. -

Media Technology and Society

MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIETY Media Technology and Society offers a comprehensive account of the history of communications technologies, from the telegraph to the Internet. Winston argues that the development of new media, from the telephone to computers, satellite, camcorders and CD-ROM, is the product of a constant play-off between social necessity and suppression: the unwritten ‘law’ by which new technologies are introduced into society. Winston’s fascinating account challenges the concept of a ‘revolution’ in communications technology by highlighting the long histories of such developments. The fax was introduced in 1847. The idea of television was patented in 1884. Digitalisation was demonstrated in 1938. Even the concept of the ‘web’ dates back to 1945. Winston examines why some prototypes are abandoned, and why many ‘inventions’ are created simultaneously by innovators unaware of each other’s existence, and shows how new industries develop around these inventions, providing media products for a mass audience. Challenging the popular myth of a present-day ‘Information Revolution’, Media Technology and Society is essential reading for anyone interested in the social impact of technological change. Brian Winston is Head of the School of Communication, Design and Media at the University of Westminster. He has been Dean of the College of Communications at the Pennsylvania State University, Chair of Cinema Studies at New York University and Founding Research Director of the Glasgow University Media Group. His books include Claiming the Real (1995). As a television professional, he has worked on World in Action and has an Emmy for documentary script-writing. MEDIA TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIETY A HISTORY: FROM THE TELEGRAPH TO THE INTERNET BrianWinston London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

Wave-Particle Duality 波粒二象性

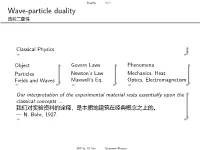

Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality 波粒二象性 Classical Physics Object Govern Laws Phenomena Particles Newton’s Law Mechanics, Heat Fields and Waves Maxwell’s Eq. Optics, Electromagnetism Our interpretation of the experimental material rests essentially upon the classical concepts ... 我们对实验资料的诠释,是本质地建筑在经典概念之上的。 — N. Bohr, 1927. SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Photon 电磁波 Electromagnetic wave, James Clerk Maxwell: Maxwell’s Equations, 1860; Heinrich Hertz, 1888 黑体辐射 Blackbody radiation, Max PlanckNP1918: Planck’s constant, 1900 光电效应 Photoelectric effect, Albert EinsteinNP1921: photons, 1905 All these fifty years of conscious brooding have brought me no nearer to the answer to the question, “What are light quanta?” Nowadays every Tom, Dick and Harry thinks he knows it, but he is mistaken. 这五十年来的思考,没有使我更加接近 “什么是光量子?” 这个问题的 答案。如今,每个人都以为自己知道这个答案,但其实是被误导了。 — Albert Einstein, to Michael Besso, 1954 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Electron Electron in an Atom Electron: Cathode rays 阴极射线 Joseph John Thomson, 1897 J. J. ThomsonNP1906 1856-1940 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Wave-particle duality — Electron Electron in an Atom Electron: 阴极射线 Cathode rays, Joseph Thomson, 1897 Atoms: 行星模型 Planetary model, Ernest Rutherford, 1911 E. RutherfordNC1908 1871-1937 SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Spectrum of Atomic Hydrogen Spectroscopy , Fingerprints of atoms & molecules ... Atomic Hydrogen Johann Jakob Balmer, 1885 n2 λ = 364:56 n2−4 (nm), n =3,4,5,6 Johannes Rydberg, 1888 1 1 − 1 ν = λ = R( n2 n02 ) R = 109677cm−1 4 × 107/364:56 = 109721 RH = 109677.5834... SM Hu, YJ Yan Quantum Physics Duality Bohr Bohr’s Theory — Electron in Atomic Hydrogen Electron in an Atom Electron: 阴极射线 Cathode rays, Joseph Thomson, 1897 Atoms: 行星模型 Planetary model, Ernest Rutherford, 1911 Spectrum of H: Balmer series, Johann Jakob Balmer, 1885 Quantization energy to H atom, Niels Bohr, 1913 Bohr’s Assumption There are certain allowed orbits for which the electron has a fixed energy.