The Politics of Listlessness: the Democrats Since 1981

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journalism's Backseat Drivers. American Journalism

V. Journalism's The ascendant blogosphere has rattled the news media with its tough critiques and nonstop scrutiny of their reporting. But the relationship between the two is nfiore complex than it might seem. In fact, if they stay out of the defensive crouch, the battered Backseat mainstream media may profit from the often vexing encounters. BY BARB PALSER hese are beleaguered times for news organizations. As if their problems "We see you behind the curtain...and we're not impressed by either with rampant ethical lapses and declin- ing readership and viewersbip aren't your bluster or your insults. You aren't higher beings, and everybody out enough, their competence and motives are being challenged by outsiders with here has the right—and ability—to fact-check your asses, and call you tbe gall to call them out before a global audience. on it when you screw up and/or say something stupid. You, and Eason Journalists are in the hot seat, their feet held to tbe flames by citizen bloggers Jordan, and Dan Rather, and anybody else in print or on television who believe mainstream media are no more trustwortby tban tbe politicians don't get free passes because you call yourself journalists.'" and corporations tbey cover, tbat journal- ists tbemselves bave become too lazy, too — Vodkapundit blogger Will Collier responding to CJR cloistered, too self-rigbteous to be tbe watcbdogs tbey once were. Or even to rec- Daily Managing Editor Steve Lovelady's characterization ognize what's news. Some track tbe trend back to late of bloggers as "salivating morons" 2002, wben bloggers latcbed onto U.S. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

Roots of Anger3 Notes

The Real Explanation for the Tax Rebellion and the Size of Government H. William Batt, Ph.D., February 16, 2011 The antipathy toward taxes, and by extension toward government itself, has its roots, I believe, in a distortion of economic theory that took place a century ago. Prior to that time, there was a tacit, if not explicit, understanding that the wealth and bounty that grew from common effort along with the gifts of nature should be the source of finance recaptured by society and used to pay for public services. Since surplus economic productivity is jointly produced, it was the proper source of taxation. Only government can appropriately provide these services since they are in today's language "public goods." On the other hand, wealth that was created by the people's own brains and brawn was rightfully theirs and theirs alone. Taxing people's labor, or the products thereof, was not only wrong but was tantamount to theft.1 Today the resentment people feel about taxes on their hard-earned money has reached a point close to delegitimizing the income tax and government itself. Estimates of actual tax cheating are put at about 15 percent, but fully half the population believes that it would be okay to cheat if one wouldn’t be caught.2 It has taken over a century for this all to explode. But taking the long view of tax history one could argue that this is not only understandable but also inevitable. Had economic arrangements been done as they were in earlier times there would likely be far less such resistance to taxation and perhaps even a sense of social duty to pay one’s share of taxes. -

Document Country: Hungary

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 5 Tab Number: 18 Document Title: Central European Electoral Systems Symposium Report, Budapest, Hungary; July Document Date: 1991 Document Country: Hungary IFES ID: R01656 ••::_.':.&:" I ....~ .Y International Foundation for Electoral Systems ~ 1620 I STREET. NW • SUITE 611 • WASHINGTON. DC 20006' 12021828-8507' FAX 12021 452-0804 I I I I I I I I I I I I I DO NOT REMOVE FROM I IFES RESOURCE CENTER! I 80ARDOF F. Clifton White Patricia Hurar James M. Cannon Randal C Teague DIRECTORS Chairman Secretary Counsel I Richard M. Scammon Charles Manatt John C. White Richard W. Soudriene I Vice Chairman Treasurer Robert C. Walker Director I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I I Statement by Mr. Clifton White, Chairman of IRES I II Elections in Hungary and Slovakia The National Election Committee of Hungary, by Paul Kara,' I Secretary, National Election Committee; I The Experience of Elections in the Slovak Republic, by Peter' I Bercik, Secretary of the Slovak Election Commission. III Building a Grass Roots Civic Association Bulgarian Association of Fair Elections and Civil Rights, by I Miroslav Sevlievski, secretary General; Citizen Education Its Importance in Latin America and I Central Europe, by Monica Jiminez de Barros, Executive Director, PARTICIPA. I IV Electoral and Representative Systems of Nominating and Voting Controversies of Polish Electoral Law, by Senator Jerzy. I Stepien, Chairman of Local Elections' Bureau; Commentary on Proportional Representation by Means of the , Transferable Vote, by Louise McDonough, Chairman, Association I of Parliamentary Returning Officers. V Political Parties I The Role of Political Parties, by Michael Pinto-Duschinsky, Senior Lecturer in Government, BruneI University; I The Role of Political Parties Prospect for Partisan Democratic strengthening in Latin America, by Gabriel Murillo Castana, Chairman, Department of Political Science, University I of the Andes. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Pace University) Political Journalism 374-001 Fall Semester 2008 Thursday 1:30-4:15 P.M

1 George Mason University (in collaboration with C-SPAN, the University of Denver, The Cable Center and Pace University) Political Journalism 374-001 Fall Semester 2008 Thursday 1:30-4:15 p.m. (14 sessions) 328 and 455 Innovation Hall Instructor: Steve Klein (with Steve Scully and Chris Malone) POLITICS & THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY A comprehensive course focusing on the 2008 presidential campaign & the presidency Websites: http://www.C-SPAN.org/Distance_Learning/ http://mason.gmu.edu/~sklein1/ http://webpage.pace.edu/cmalone/ 2 “For most Americans the president is the focal point of public life. Almost every day, they see the president on television newscasts interpreting current events, meeting with foreign dignitaries, proposing policy, or grappling with national problems. This person appears to be in charge, and such recurrent images of an engaged leader are reassuring. But the reality of the presidency rests on a very different truth: presidents are seldom in command and usually must negotiate with others to achieve their goals….Those who invented the presidency in 1787 did not expect the office to become the nation’s central political institution…Students of the presidency commonly divide the office’s developments into two major periods: traditional and modern. In the traditional era, presidential power was relatively limited, and Congress was the primary policymaker. The modern era, on the other hand, is typified by the presidential dominance in the policymaking process and a significant expansion of the president’s powers and resources.” Joseph A. Pika Anthony Maltese Co-Authors, “The Politics of the Presidency” When the Framers sat down in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to draft the Constitution, they had little idea of how they were going to design the office of the presidency. -

Owner's Signature Required for Party by SCOTT BEARBY Owner/Manager Must Agree to Take News Staff Responsibility

------------------------------ Dance studio - page 3 VOL XIX, NO. 33 tht· indqwndt·nt .,llllkllt nt·w,papn 'lT\ ing 1101n dame and 'aint mary·, MONDAY, OCTOBER 8, 1984 Owner's signature required for party By SCOTT BEARBY owner/manager must agree to take News Staff responsibility. Residence halls seem to be taking a cautious attitude Planning for an off-campus event toward off-campus events. has become more complex of a as a "With all the inconsistencies result of a directive issued by the Of we're confused as to what's accep fice of Student Affairs. This directive table," said Alumni Hall president details a procedure in which Carl Whelahan. Alumni commis residence halls and social groups sioners are compensating by plan must obtain, in writing, an agree ning more in-hall events, as are most ment from the ownermanager of the other halls. establishment stating he will take re Although there have been some sponsibility for any mishap which off-campus activities, others have may take place on the premises. been cancelled. Lewis Hall can Under the agreement the celled a cruise, because there was owner/manager assumes responsi "not enough Interest," because alco bility for the supplying, providing, hol could not be t;erved to those un· distributing and selling of any alco der the legal drinking age, said Lewis hol present at the event; for provid President Debbie Doherty. ing bartenders at the event; and for Despite the new policy, hall com checking identification in order to missioners have not abandoned the monltor the consumption of alcohol idea of off-campus events. -

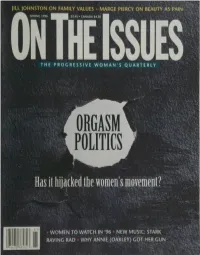

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Reagan's Victory

Reagan’s ictory How HeV Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison Foreword by William J. Bennett Reagan’s Victory: How He Built His Winning Coalition By Robert G. Morrison 1 FOREWORD By William J. Bennett Ronald Reagan always called me on my birthday. Even after he had left the White House, he continued to call me on my birthday. He called all his Cabinet members and close asso- ciates on their birthdays. I’ve never known another man in public life who did that. I could tell that Alzheimer’s had laid its firm grip on his mind when those calls stopped coming. The President would have agreed with the sign borne by hundreds of pro-life marchers each January 22nd: “Doesn’t Everyone Deserve a Birth Day?” Reagan’s pro-life convic- tions were an integral part of who he was. All of us who served him knew that. Many of my colleagues in the Reagan administration were pro-choice. Reagan never treat- ed any of his team with less than full respect and full loyalty for that. But as for the Reagan administration, it was a pro-life administration. I was the second choice of Reagan’s to head the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It was my first appointment in a Republican administration. I was a Democrat. Reagan had chosen me after a well-known Southern historian and literary critic hurt his candidacy by criticizing Abraham Lincoln. My appointment became controversial within the Reagan ranks because the Gipper was highly popular in the South, where residual animosities toward Lincoln could still be found. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover -

Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics

Journal of Political Science Volume 23 Number 1 Article 2 November 1995 Forgotten But Not Gone: Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics Robert P. Steed Tod A. Baker Laurence W. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Steed, Robert P.; Baker, Tod A.; and Moreland, Laurence W. (1995) "Forgotten But Not Gone: Mountain Republicans and Contemporary Southern Party Politics," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 23 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol23/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORGOTTEN BUT NOT GONE: MOUNTAIN REPUBLICANS AND CONTEMPORARY SOUTHERN PARTY POLITICS Robert P. Steed, The Citadel Tod A. Baker, The Citadel Laurence W. Moreland, The Citadel Introduction During the period of Democratic Party dominance of southern politics, Republicans were found mainly in the mountainous areas of western Virginia, western North Carolina, and eastern Tennessee and in a few other counties (e.g., the German counties of eas't central Te_xas) scattered sparsely in the region. Never strong enough to control statewide elections, Republicans in these areas were competitive locally, frequently succeeding in winning local offices. 1 As southern politics changed dramatically during the post-World War II period, research on the region's parties understandably focused on the growth of Republican support and organizational development in those geographic areas and electoral arenas historically characterized by Democratic control.