The 'Inevitability' of Corruption in Greek Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

Media Release World Leagues Forum Schützengasse 4 8001 Zürich Switzerland The World Leagues Forum: “Domestic leagues unanimously reject the super league concept but also request better representation in the football governance” Zurich, Switzerland – 23 April 2021 – Following the recent events on the European breakaway league, the board of the World Leagues Forum (WLF), the association which represents professional football leagues on a world level met today. This board includes the following leagues: Premier League (England), Ligue de Football Professionnel (France), DFL Deutsche Fußball Liga (Germany), Lega Serie A (Italy), Russian Premier League (Russia), LaLiga (Spain), Premier League Soccer (South Africa), LigaPro (Ecuador), Major League Soccer (USA), Liga MX (Mexico), J.League (Japan) and Professional Saudi League (Saudi Arabia). The WLF issues the following statement: “The World Leagues Forum not only rejects the concept of the super league, but also requests better representation of the leagues in football governance. This is the consequence of the lessons which can be drawn from this week’s events: One: The European super league project reflected the money-driven vision a small group of already super rich clubs. This vision has been rejected by everyone in football and outside football. But most importantly, it has been rejected by the fans. It has shown that sport values such as sporting merit and solidarity must always prevail. Two: Any international competition where some clubs would have a permanent right to play without qualifying from domestic leagues is a terrible idea. Not only it disregards the values of sport, but it neglects the importance of domestic competitions from an historical, from an economic, and from a fan perspective. -

Table of Contents 1. Introduction

Table of contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Moments of Glory.........................................................................................................................5 1.2. The short history of Communism .................................................................................................6 1.2.1. The importance of October Revolution .....................................................................................6 1.2.2. Why did communism fail?.........................................................................................................7 1.3. The history of football under communism....................................................................................8 1.3.1. One republic, at least one club...................................................................................................8 1.3.2. Ministry of Defence vs. Ministry of Internal Affairs.................................................................9 1.3.3. Frozen in the moment of The Miracle of Bern ........................................................................11 1.3.4. Two times runners - up ............................................................................................................11 1.3.5. Two times third ........................................................................................................................12 1.3.6. Albania and Moldova...............................................................................................................13 -

Ιωάννης I. Ντουρουντός Msc, Phd Ioannisi. Douroudos Msc

Ιωάννης Ι. Ντουρουντός, Ph.D. 2014 Ioannis I. Douroudos, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae CURRICULUM VITAE Ιωάννης I. Ντουρουντός MSc, PhD Ioannis I. Douroudos MSc, PhD (IOANNIS NTOUROUNTOS, Latin) Personal Information Current Occupation Conditioning and Performance Specialist Biochemistry and Exercise Physiology (Ergophysiologist) (U.E.F.A A Procedures) Date of birth November 19th, 1978 Nationality Hellenic Languages Greek (native), English Telephone number +30 6944376007 (mobile) Fax number Email: [email protected] www.douroudos.gr Scienceweb.gr (Science Committee Member) Performance22.gr Pub Med Link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=douroudos (e - Publications) Facebook: douroudos ioannis 1 Ιωάννης Ι. Ντουρουντός, Ph.D. 2014 Ioannis I. Douroudos, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Education Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Institution: Democritus University of Thrace (2004 - 2010) Department: Physical Education and Sport Sciences Advisor: Taxildaris K – Fatouros I.I. Major: Exercise Physiology and Biochemistry Ergophysiology Dissertation title: The age effects in human physiological adaptation and oxidative stress during exercise Grade: 10/10 Masters of Sciences (M.S.) (2001 - 2004) Institution: Democritus University of Thrace Department: Physical Education and Sport Sciences Advisor: Taxildaris K – Fatouros I.I. Are of concentration: Sciences of Training, Nutrition Thesis title: Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate (ΝaHCO3) intake, at biochemical parameters of acid base balance and performance, during exercise Grade: 10/10 Bachelors (B.S.) Institution: Democritus University of Thrace (1996 - 2000) Department: Physical Education and Sport Sciences 2 Ιωάννης Ι. Ντουρουντός, Ph.D. 2014 Ioannis I. Douroudos, Ph.D. Curriculum Vitae Other Certifications 1. Certificate in Rehabilitation in Sports Injuries and Chronic Disease (Grade 9.00). 2. U.E.F.A A (Certification) 3. -

Sports Television Programming

Sports Television Programming: Content Selection, Strategies and Decision Making. A comparative study of the UK and Greek markets. Sotiria Tsoumita A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree at the University of Stirling January 2013 Acknowledgements There are many people that I would like to thank for their help, support and contribution to this project starting from my two supervisors: Dr Richard Haynes for all his feedback, suggestions for literature, ideas and specialist knowledge in the UK market and Prof. Wray Vamplew for all the corrections, suggestions, for the enthusiasm he showed for the subject and for allowing me the freedom to follow my interests and make decisions. A special thanks because he was also involved in the project from the very first day that I submitted the idea to the university. I would also like to thank Prof. Raymond Boyle who acted as a second supervisor at the beginning of my PhD studies. This thesis would not have existed if it wasn’t for all the interviewees who kindly accepted to share their knowledge, experiences and opinions and responded to all my questions. Taking the interviews was the most enjoyable and rewarding part of the research. I would particularly like to thank those who helped me arrange new interviews: Henry Birtles for contacting Ben Nicholas, Vasilis Panagiotakis for arranging a number of interviews with colleagues in Greece and Gabrielle Marcotti who introduced me to Nicola Antognetti who helped me contact Andrea Radrizzani and Marc Rautenberg. Many thanks to friends and colleagues for keeping an eye on new developments in the UK and Greek television markets that could be of interest to my project. -

Reusch Goalkeeper Review / September 2017 Name Games Played Team Position Name Games Played Team Position Name Games Played Team Position

EUROPEAN TOP LEAGUES REUSCH GOALKEEPER REVIEW / SEPTEMBER 2017 NAME GAMES PLAYED TEAM POSITION NAME GAMES PLAYED TEAM POSITION NAME GAMES PLAYED TEAM POSITION • UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE • SERIE A - ITALY • EREDIVISIE - NETHERLANDS Brad Jones 1 / 1 Feyenoord Rotterdam (Gr. F) 4 / 4 Andrea Consigli 6 / 6 Sassuolo Calcio 15 / 20 Brad Jones 5 / 6 Feyenoord Rotterdam 4 / 18 Alessio Cragno 6 / 6 Cagliari Calcio 13 / 20 Remko Pasveer 5 / 6 Vitesse Arnheim 3 / 18 • UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE Salvatore Sirigu 6 / 6 FC Torino 8 / 20 Wouter van der Steen 3 / 6 SC Heerenveen 2 / 18 Yoan Cardinale 1 / 1 OGC Nice (Gr. K) 1 / 4 Marco Sportiello 6 / 6 AC Fiorentina 12 / 20 Eloy Room 0 / 6 PSV Eindhoven 1 / 18 Florin Nita 1 / 1 Steaua Bucharest (Gr. G) 1 / 4 Christian Puggioni 5 / 5 UC Sampdoria 7 / 20 Luuk Koopmans 0 / 6 PSV Eindhoven 1 / 18 Guy Haimov 1 / 1 Hapoel Be'er Sheva (Gr. G) 2 / 4 Antonio Mirante 5 / 6 FC Bologna 11 / 20 Gino Coutinho 0 / 6 AZ Alkmaar 5 / 18 Remko Pasveer 1 / 1 Vitesse Arnheim (Gr. K) 3 / 4 Simone Scuffet 5 / 6 Udinese Calcio 17 / 20 Nicola Leali 1 / 1 SV Zulte Waregem (Gr. K) 4 / 4 Angelo Da Costa 1 / 6 FC Bologna 11 / 20 • PRO LEAGUE - BELGIUM Zvonimir Mikulic 1 / 1 FC Sheriff (Gr. F) 3 / 4 Davide Borselini 0 / 6 Udinese Calcio 17 / 20 Nicola Leali 3 / 8 SV Zulte Waregem 3 / 16 Marco Storari 0 / 1 AC Milan (Gr. D) 1 / 4 Michele Cerofolini 0 / 6 AC Fiorentina 12 / 20 Mike Vanhamel 3 / 8 KV Oostende 16 / 16 Dario Marzino 0 / 1 BSC Young Boys (Gr. -

The Financial Landscape of European Football Foreword the Financial Landscape of European Football > Foreword

The Financial Landscape of European Football Foreword The Financial Landscape of European Football > Foreword Foreword (1/2) Introduction COVID-19 The essence of exciting professional football competitions is having sporting merit The world at the beginning of this year looked very different. The COVID-19 and sporting ability as the deciding factor in winning or losing. This leads to pandemic surprised societies and the impact was and is still enormous for many, competitions filled with matches where unpredictable outcomes are possible and including the entire football industry. All competitions were stopped, and football where the excitement and passion for the fans lies in the possibility their side could showed a great level of adaptability and flexibility to allow many leagues to triumph. resume their competitions, first with matches to be played behind closed doors and then, where possible, with the gradual return of fans to the stadiums. The objective of the European Leagues (EL), as representative of the domestic league organisers, is to enhance and protect competitive balance within The sporting, financial and social impact is immense in the short term, while the domestic football competitions. mid and long-term effects are still very uncertain because of the unpredictable development of the virus. However, it is already clear that the pandemic will lead At the end of 2019, the EL decided to make a study to better understand the to billions of lost revenue for football, with the consequence that hundreds of financial landscape of European professional football and its impact on professional clubs of all sizes, playing in many different domestic competitions, polarisation and ultimately sporting competitive balance. -

First Division Clubs in Europe 2018/19

Address List - Liste d’adresses - Adressverzeichnis 2018/19 First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs de première division en Europe Klubs der ersten Divisionen in Europa WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES | INHALTSVERZEICHNIS UEFA CLUB COMPETITIONS CALENDAR – 2018/19 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 3 CALENDAR – 2018/19 UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 4 UEFA MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS Albania | Albanie | Albanien 5 Andorra | Andorre | Andorra 7 Armenia | Arménie | Armenien 9 Austria | Autriche | Österreich 11 Azerbaijan | Azerbaïdjan | Aserbaidschan 13 Belarus | Bélarus | Belarus 15 Belgium | Belgique | Belgien 17 Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bosnie-Herzégovine | Bosnien-Herzegowina 19 Bulgaria | Bulgarie | Bulgarien 21 Croatia | Croatie | Kroatien 23 Cyprus | Chypre | Zypern 25 Czech Republic | République tchèque | Tschechische Republik 27 Denmark | Danemark | Dänemark 29 England | Angleterre | England 31 Estonia | Estonie | Estland 33 Faroe Islands | Îles Féroé | Färöer-Inseln 35 Finland | Finlande | Finnland 37 France | France | Frankreich 39 Georgia | Géorgie | Georgien 41 Germany | Allemagne | Deutschland 43 Gibraltar | Gibraltar | Gibraltar 45 Greece | Grèce | Griechenland 47 Hungary | Hongrie | Ungarn 49 Iceland | Islande | Island 51 Israel | Israël | Israel 53 Italy | Italie | Italien 55 Kazakhstan | Kazakhstan | Kasachstan 57 Kosovo | Kosovo | Kosovo 59 Latvia | Lettonie | Lettland 61 Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein 63 Lithuania | Lituanie | Litauen 65 Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Luxemburg 67 Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | ARY -

Frontex La Frontière Du Déni

FRONTEX ENTRE GRÈCE ET TURQUIE : LA FRONTIÈRE DU DÉNI FIDH - Migreurop - REMDH Ont participé à ce rapport : Katherine Booth (FIDH), Shadia El Dardiry (REMDH), Laura Grant (Consultante migration et droits humains auprès de la FIDH), Caroline Intrand (CIRÉ-Migreurop), Anitta Kynsilehto (REMDH), Regina Mantanika (chercheuse associée à Migreurop), Marie Martin (Migreurop), Claire Rodier (Migreurop), Louise Tassin (chercheuse associée à Migreurop), Eva Ottavy (Migreurop) Cartograhie : Olivier Clochard Photographies : Louise Tassin et Eva Ottavy Maquette : Alterpage Remerciements : A chacun(e) des participant(e)s aux entretiens pour leur disponibilité. Aux as- sociations membres et partenaires de nos organisations et à celles rencontrées au cours de la mission en Turquie (Helsinki Citizen Assembly-Refugee Advocacy Support Program (HCA-RASP), Human Rights Association (IHD) et Mülteci der) ainsi qu’en Grèce (la ligue grecque des droits de l’homme, le Greek Council for Refugees (GCR), le Village of all together, etc.) pour leur soutien d’importance lors de la mission et pour la rédaction de ce rapport. Cette mission a été par ailleurs grandement fa- cilitée par le soutien des eurodéputées Mme Cornelia Ernst, Mme Hélène Flautre, et Mme Marie-Christine Vergiat et de leurs assistants ; des députés grecs Afroditi Stampouli et Giannis Zerdelis, de leurs assistants ainsi que du conseil municipal de Mytilène. Nous adressons, enfin, nos plus sincères remerciements aux migrant(e)s qui ont accepté de partager la réalité de leur situation avec notre délégation et nous ont autorisées à utiliser leur témoignage aux fins de cette étude. Ce projet est soutenu par l’Agence danoise d’aide au développement internatio- nal (Danida), le Programme européen pour l’intégration et la migration (EPIM) – une initiative conjointe des fondations du réseau européen des fondations (NEF) – et de l’Agence internationale suédoise de coopération au développement (Sida). -

Responsabilidade Social No Desporto

Responsabilidade Social no desporto por João Pedro Paiva de Pinho Relatório de Estágio para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Economia pela Faculdade de Economia do Porto Orientado por: Professor Dr. Manuel Emílio Mota Almeida Castelo Branco Supervisionado por: Pedro Vieira - ValeConsultores Unipessoal, Lda setembro, 2017 Agradecimentos A elaboração deste relatório foi um enorme desafio para mim uma vez que representa o culminar da minha vida académica. É importante para mim realizar este agradecimento a todas as pessoas fundamentais na minha vida. Em primeiro lugar, um agradecimento aos meus pais, por todos os esforços na minha educação e pelo exemplo diário de entrega e dedicação. Um agradecimento também ao meu irmão, à minha restante família e aos meus amigos pelo acompanhamento e motivação para a minha vida académica. Outro agradecimento, este especial, à minha namorada, por todo o acompanhamento ao longo desta fase da minha vida, motivação e incentivo para que este relatório fosse realizado da melhor forma possível. Igualmente importante, um agradecimento ao meu orientador, Professor Dr. Manuel Emílio Mota Almeida Castelo Branco, pela disponibilidade demonstrada e pela brevidade e qualidade nos conselhos dados. Por fim, um agradecimento ao meu supervisor na empresa acolhedora do estágio, Pedro Vieira e ao responsável pela empresa, o Dr. Luís Vale, por toda a disponibilidade, paciência e acompanhamento ao longo dos seis meses de estágio. ii Resumo Este relatório é o produto final de um estágio curricular de seis meses na empresa ValeConsultores Unipessoal, Lda, uma empresa de consultoria que constantemente se procura adaptar às necessidades do mercado para potencializar o seu sucesso. -

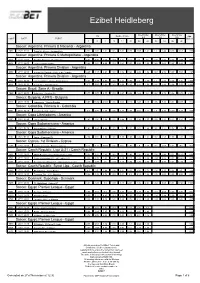

Ezibet Heidleberg

Ezibet Heidleberg Over/Under Over/Under Over/Under 1X2 Double chance 2.5 1.5 0.5 Add. CODE DATE EVENT Markets 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 Ov Un Ov Un Ov Un Soccer: Argentina. Primera B Nacional - Argentina 2492 28-11 02:05 Deportivo Moron - Agropecuario 2.92 2.88 2.67 1.45 1.39 1.38 2.69 1.42 1.5 2.44 1.08 6.51 +89 Soccer: Argentina. Primera C Metropolitana - Argentina 8376 27-11 22:00 Sportivo Barracas - Berazategui 1.87 3.26 3.78 1.19 1.25 1.75 2.2 1.6 1.38 2.82 1.05 7.49 +48 4836 27-11 22:00 Lujan - Excursionistas 1.69 3.41 4.55 1.13 1.23 1.95 2.33 1.53 1.42 2.68 1.07 6.84 +48 Soccer: Argentina. Primera Division - Argentina 4959 27-11 22:00 Arsenal De Sarandi - Talleres de Cordoba 4.25 3.17 2.01 1.81 1.36 1.23 2.45 1.52 1.43 2.72 1.07 7.51 +97 Soccer: Argentina. Primera Division - Argentina 7763 28-11 00:15 Velez Sarsfield - Olimpo Bahia Blanca 1.83 3.37 4.86 1.18 1.33 1.99 2.3 1.59 1.4 2.83 1.07 7.92 +100 4942 28-11 02:30 Temperley - San Martin SJ 2.7 3.05 2.84 1.43 1.38 1.47 2.31 1.58 1.41 2.84 1.06 7.97 +100 Soccer: Brazil. -

2018/19 Clubs De Première Division En Europe

Address List - Liste d’adresses - Adressverzeichnis 2018/19 First Division Clubs in Europe Clubs de première division en Europe Klubs der ersten Divisionen in Europa WE CARE ABOUT FOOTBALL CONTENTS | TABLE DES MATIÈRES | INHALTSVERZEICHNIS UEFA CLUB COMPETITIONS CALENDAR – 2018/19 UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 3 CALENDAR – 2018/19 UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE 4 UEFA MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS Albania | Albanie | Albanien 5 Andorra | Andorre | Andorra 7 Armenia | Arménie | Armenien 9 Austria | Autriche | Österreich 11 Azerbaijan | Azerbaïdjan | Aserbaidschan 13 Belarus | Bélarus | Belarus 15 Belgium | Belgique | Belgien 17 Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bosnie-Herzégovine | Bosnien-Herzegowina 19 Bulgaria | Bulgarie | Bulgarien 21 Croatia | Croatie | Kroatien 23 Cyprus | Chypre | Zypern 25 Czech Republic | République tchèque | Tschechische Republik 27 Denmark | Danemark | Dänemark 29 England | Angleterre | England 31 Estonia | Estonie | Estland 33 Faroe Islands | Îles Féroé | Färöer-Inseln 35 Finland | Finlande | Finnland 37 France | France | Frankreich 39 Georgia | Géorgie | Georgien 41 Germany | Allemagne | Deutschland 43 Gibraltar | Gibraltar | Gibraltar 45 Greece | Grèce | Griechenland 47 Hungary | Hongrie | Ungarn 49 Iceland | Islande | Island 51 Israel | Israël | Israel 53 Italy | Italie | Italien 55 Kazakhstan | Kazakhstan | Kasachstan 57 Kosovo | Kosovo | Kosovo 59 Latvia | Lettonie | Lettland 61 Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein 63 Lithuania | Lituanie | Litauen 65 Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Luxemburg 67 Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | ARY -

Ιωάννης I. Ντουρουντός (Phd, M.Sc., B.Sc.) Ioannis I

Δρ. Ιωάννης Ι. Ντουρουντός 2017 Dr. Ioannis I. Douroudos Curriculum Dr. Ioannis I. Ntourountos Vitae CURRICULUM VITAE Ιωάννης I. Ντουρουντός (PhD, M.Sc., B.Sc.) Ioannis I. Douroudos (PhD, M.Sc., B.Sc.) (IOANNIS NTOUROUNTOS, Latin) Personal Information: Current Occupation Conditioning and Athletic Performance Specialist in Professional Soccer Industry Biochemistry and Exercise Physiologist U.E.F.A (A) (Licensed coach) Date of birth November 19th, 1978 Nationality Hellenic Languages Greek (native), English Status Married Telephone number +30 6944376007 (mobile) Fax number +30 2130417617 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.douroudos.gr Honors • x1 Greek Super League Championship Winner (Olympiacos FC 2016-2017) • Participation in 5 games @ Group stages - 2017-2018 UEFA Champions league (Olympiacos FC) Pub Med Link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=douroudos (e - Publications) Facebook: douroudos ioannis, LinkedIn: Douroudos (Ntourountos) Ioannis Reseachgate: Douroudos (Ntourountos) Ioannis 1 Δρ. Ιωάννης Ι. Ντουρουντός 2017 Dr. Ioannis I. Douroudos Curriculum Dr. Ioannis I. Ntourountos Vitae Περίληψη Βιογραφικού Σημειώματος (GR) Ο Ιωάννης Ντουρουντός είναι κάτοχος διδακτορικού διπλώματος στη Φυσιολογία και Βιοχημεία της Άσκησης (Τ.Ε.Φ.Α.Α. του Δ.Π.Θ). Εργάζεται ως Προπονητής Φυσικής Κατάστασης στο Ποδόσφαιρο (U.E.F.A. A Certification) & Εργοφυσιολόγος. Συνεργάστηκε με ποδοσφαιρικές ομάδες επαγγελματικής κατηγορίας (Π.Α.Ε. Ολυμπιακός, Al Shabab, AL Raed S. FC, Απόλλων Λεμεσού, Π.Α.Ε. Λεβαδειακός, Π.Α.Ε. Πανιώνιος, Π.Α.Ε. Παναιτωλικός, Π.Α.Ε. Πανθρακικός, Π.Α.Ε. Skoda Ξάνθη). Το 2004 απέκτησε μεταπτυχιακό δίπλωμα Προπονητικής με ερευνητικό έργο στα Διατροφικά Συμπληρώματα και Μεγιστοποίηση της Απόδοσης. Αποτέλεσε ενεργό μέλος του Εργαστηρίου Προπονητικής και Φυσικής Απόδοσης του Τ.Ε.Φ.Α.Α.